2024-030 The State Bar of California

It Must Continue to Achieve Cost Savings and Reduce Its Growing Backlog of Disciplinary Cases

Published: February 27, 2025Report Number: 2024-030

February 27, 2025

2024-030

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As required by Business and Professions Code section 6145, my office conducted an audit of the State Bar of California (State Bar) and its operations, and we determined that the State Bar must continue its focus on achieving cost savings and addressing its backlog of attorney discipline cases. Additionally, while enrollment and racial diversity have increased in the California law schools overseen by the State Bar, the oversight fees it imposes on these schools lack support.

Although the Legislature approved attorney licensing fee increases for 2025 and the State Bar has taken some cost-savings measures, stagnating revenue and increasing personnel costs have led its general fund to a deficit in four of the last five years, from 2019 through 2023. The State Bar is in the process of implementing two significant cost-savings measures: a reduction in workforce and a reduction in the costs of administering the California Bar Examination. However, both efforts have yet to be fully implemented and the amount of expected cost savings are unclear.

We also reviewed the State Bar’s attorney discipline case backlog and found that it continues to grow. With its current resources, the State Bar has been unable to meet its proposed case processing standards. Further, the State Bar has yet to formally adopt these standards as benchmarks against which to measure its progress in shortening timelines and reducing its backlog of open cases. Nevertheless, certain measures, such as a diversion program, have increased the State Bar’s efficiency in resolving cases.

Additionally, we found that enrollment and racial diversity in law schools the State Bar oversees has grown from 2013 through 2023, despite the closures of 19 of these schools during that same period. As part of the State Bar’s oversight of these law schools, it charges the schools fees. However, we found that the State Bar lacked a clear rationale for its methodology in setting and increasing these fees.

To address these findings, we recommend that the State Bar continue its reduction in workforce measure, adopt the proposed case processing standards, and reexamine its methodology for determining all fees for unaccredited law schools and for those accredited by the State Bar’s Committee of Bar Examiners.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| CALS | California Accredited Law School |

| DEI | diversity, equity, and inclusion |

| FTE | full-time equivalent |

| GFOA | Government Finance Officers Association |

| IOLTA | income on the Lawyers’ Trust Account |

| MBE | Multistate Bar Examination |

| NCBE | National Conference of Bar Examiners |

| OCTC | Office of the Chief Trial Counsel |

Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations

The State Bar is a public corporation within the judicial branch of California’s government that is responsible for activities that include investigating and prosecuting attorneys for rules violations, regulating certain law schools, and promoting diversity and inclusion in the legal system. The State Bar primarily supports fulfilling its mission through general fund revenue, which derives largely from mandatory licensing fees that attorneys must pay annually.

The State Bar Must Continue to Achieve Cost Savings

The State Bar’s total net financial position—the amount by which an organization’s total assets exceed its total liabilities—was $227 million in 2023. However, the State Bar was legally restricted in how it could use $220 million of those assets. For example, the State Bar receives grants from the state and federal governments and then redistributes the grant funds to legal aid organizations to accomplish such goals as providing legal assistance to Californians to prevent homelessness or foreclosure. The State Bar may use these grant funds to pay the costs of administering these grants, but it cannot use this grant revenue for its other operations. Given the restrictions on most of its funds, the State Bar relies on its general fund revenues to pay for such functions as attorney discipline, communication, and administration. Since the general fund’s expenses were higher than its revenues in 2022 and 2023, the State Bar has had to rely on the general fund’s working capital—the fund’s current assets minus its current liabilities, which the State Bar considers its reserves—to continue providing services. It expects to do the same in 2024.

To address its strained financial position, the State Bar proposed to the Legislature in April 2024 to increase its attorney licensing fees. The Legislature approved an $88 fee increase for active attorneys and a nearly $23 increase for inactive attorneys, effective January 1, 2025. However, these fee increases—by themselves—may not fully address the State Bar’s deficit spending in its general fund. In 2023 expenses exceeded revenues by $20 million, and we estimate the recent fee increases may add only $17 million in new revenue. The State Bar has also implemented cost-savings measures, but the impact of its most significant measures is still unknown. One such measure is the State Bar’s effort to reduce its workforce in 2025 to bring its staff vacancy rate from 8 percent—its current rate—to the 15 percent vacancy rate goal set forth by the Legislature. Ultimately, the State Bar does not expect to eliminate its reliance on the general fund’s working capital in 2025.

The State Bar Has a Growing Backlog of Attorney Discipline Cases

The State Bar’s Office of the Chief Trial Counsel (OCTC) investigates complaints against attorneys and can take disciplinary action. In 2021 the Legislature mandated that OCTC create standards of timeliness that reflect the goal of resolving attorney discipline cases in a timely, effective, and efficient manner. Although OCTC created and proposed standards to the Legislature in 2022, the Legislature has not yet codified them in law and the Board of Trustees of the State Bar has not formally adopted these standards. However the State Bar still works to meet them. According to the State Bar, it did not intend the proposed standards to reflect timelines that the State Bar was able to meet with its then-current resources; rather, the State Bar developed the standards according to industry best practices. On average, OCTC was able to close two of six case types within the proposed standards in 2021 and unable to close any case types within the proposed standards in 2023. According to the State Bar, OCTC has not been able to meet the proposed standards because its workload is too large. It requested 57 additional staff in 2024 to process cases in a timely manner, but the Legislature denied funding for the positions.

The lengthy case processing times lead to backlogs of open cases. The State Bar considers a case in backlog if the time the case has remained open has reached 150 percent of the proposed case processing time by case type. At the end of 2023, almost 36 percent—or approximately 2,500 cases—of the total pending cases were in backlog, the backlog having increased 6 percentage points from the end of 2022. Our review found that a case may become backlogged if the case’s complexity requires a long investigation, if the case was reassigned multiple times, or if the case was reopened because of new evidence.

OCTC has begun reducing case processing times by implementing major changes, including a team reorganization, expedited investigation procedures, and an expansion of its pilot case diversion program (pilot diversion program). In 2023 OCTC implemented a pilot diversion program to divert certain minor cases to resources other than the attorney discipline system. In 2024 the Legislature approved a $5.50 license fee increase for active attorneys to fund this program and make it permanent. We reviewed a random selection of cases opened before and after these changes were implemented, and we found that cases opened afterwards closed up to 87 percent faster than previously.

OCTC stated that because it made a large series of changes, it needs time for the changes to take effect and to evaluate how effective and efficient its system is at processing cases. The Legislature noted that although it rejected the State Bar’s request for 57 additional staff positions for OCTC to meet processing standards, the Legislature may reexamine the request in future years, depending on the expanded pilot diversion program’s effects on OCTC’s workload and staffing needs.

Enrollment and Racial Diversity Have Increased in California Law Schools, but the State Bar’s Fees for Oversight of These Schools Lack Support

The three types of law schools operating in California are unaccredited law schools registered with the State Bar (unaccredited schools), California Accredited Law Schools (CALS), which are accredited by the State Bar’s Committee of Bar Examiners, and law schools approved and accredited by the American Bar Association. Our review focuses on the two types of schools that the State Bar regulates: unaccredited schools and CALS. We reviewed enrollment and demographic data at law schools in California and found that from 2013 through 2023, the percentage of students of color increased in each type of law school. For example, in 2013, students of color made up 41 percent of students enrolled in CALS and as of 2023, students of color comprised 57 percent of students enrolled in CALS. The State Bar assesses and charges fees to CALS and to unaccredited law schools in California to fund services associated with its responsibility to regulate California law schools—including accreditation, registration, and inspection. We reviewed the State Bar’s fees and found that the recent fee increases will not eliminate the deficit in the State Bar’s law school oversight program. We also found that its fees, and its methodology for calculating and increasing its fees, differ by a school’s accreditation status and student body size. The State Bar could not offer a specific reason to explain why the fees should have these variations.

To address these findings, we recommend that the State Bar take the following actions: continue implementing its reduction-in-workforce measure, which should help it achieve the Legislature’s mandated vacancy rate goal; adopt the proposed case processing standards as benchmarks against which to measure OCTC’s progress in shortening timelines and reducing backlogs; reexamine its methodology for determining all fees for CALS and unaccredited schools; and set supportable fees for all law schools.

Agency Comments

The State Bar agreed with our recommendations and provided additional context regarding some of our conclusions.

Introduction

Background

Every person who is licensed to practice law in California and admitted to the State Bar of California (State Bar) is a licensee of the State Bar unless that individual holds office as a judge of a court of record. The State Bar is a public corporation in the judicial branch of California’s government and is governed by the 13‑member Board of Trustees of the State Bar (Board). The State Bar is subject to both state law and direction from the California State Supreme Court (Supreme Court). The State Bar investigates and disciplines attorneys for rules violations, administers the California Bar Examination (bar exam), regulates certain law schools, administers grants to organizations that provide legal services to Californians having low and moderate incomes, and promotes diversity and inclusion in the legal system.

The State Bar Uses Several Revenue Sources to Fund Its Mission

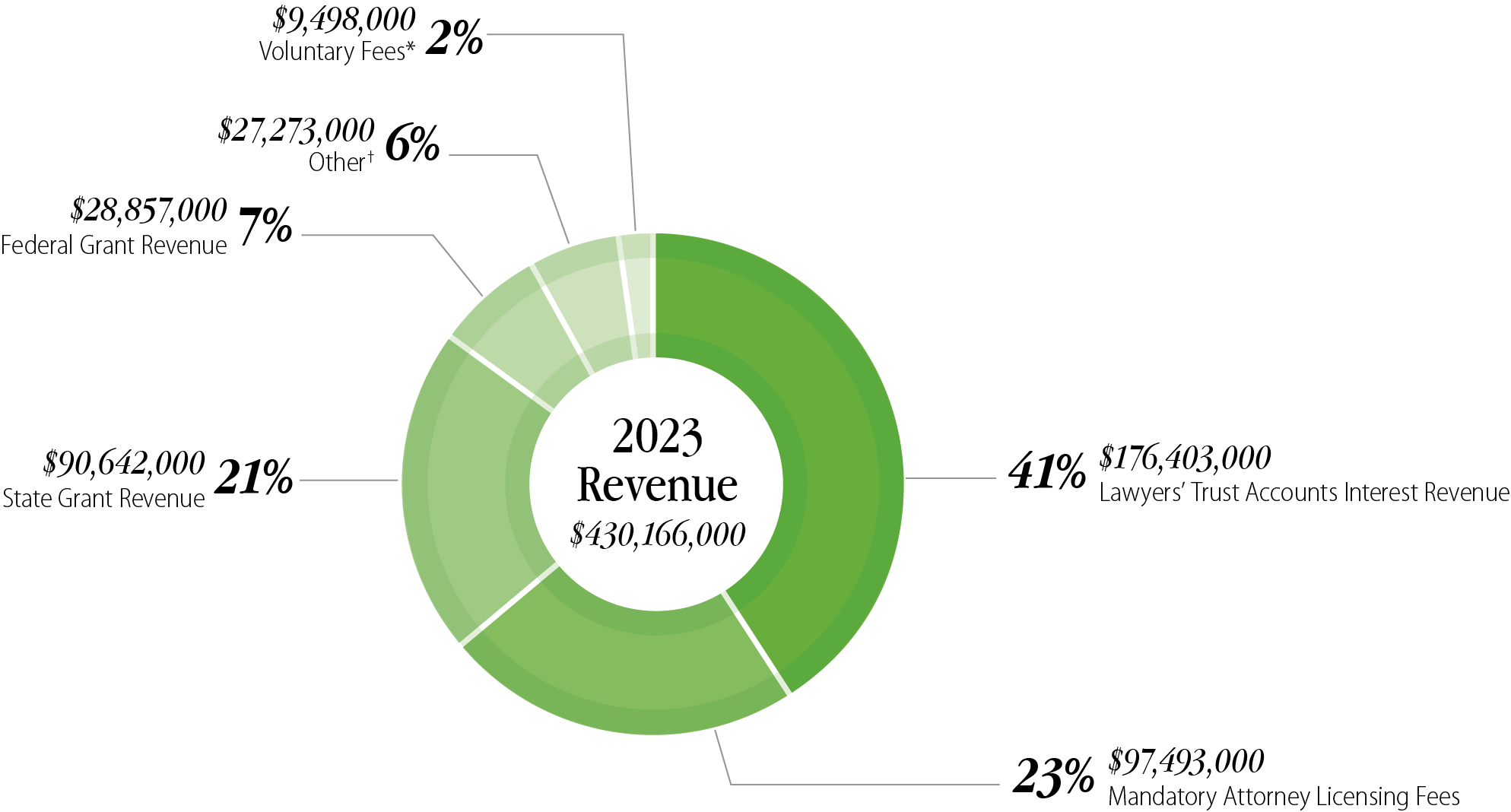

The State Bar receives revenue from three major sources: mandatory attorney licensing fees, state and federal grants, and income from Interest on Lawyers’ Trust Accounts (IOLTA), as Figure 1 shows. The Legal Services Trust Fund Commission within the State Bar administers the IOLTA. California attorneys who handle money on behalf of their client, such as settlement checks, place these funds in an IOLTA account if the funds are too small or will be held too briefly to earn interest for the clients. State law requires that the interest revenue generated by the pooled funds in an IOLTA account be used for the provision of civil legal services to indigent persons. The State Bar reported that in 2024 it distributed $180 million in IOLTA and grant funds to 110 local legal aid organizations, such as the California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation and Family Violence Law Center.

Figure 1

The State Bar Had Multiple Revenue Sources in 2023

Source: The State Bar’s 2023 audited financial statements and auditor analysis.

Note: Dollar amounts rounded to the nearest thousand.

* Voluntary fees include opt-in and opt-out fees that attorneys may elect to pay to the State Bar.

† Other revenue sources include bar exam fees, legal specialization fees, and others.

In the year 2023, the State Bar had multiple sources of revenue, which are displayed in a pie chart format in this figure. The total revenue was around four hundred thirty million dollars, a number which is presented in the center of the pie chart. Around this center, the pie is cut into pieces that correspond to the revenue sources. The larger the contribution, the greater the size of the pie a certain revenue source represents. The largest contributors to this total were Lawyers’ Trust Accounts revenue, mandatory attorney licensing fees, and state grant revenue. These revenue sources comprise forty-one percent, twenty-three percent, and twenty-one percent, respectively, of the total revenue for the year 2023. This figure does have footnotes with additional detail below it.

The State Bar also receives restricted revenue in the form of grants from the State and the federal governments. The State Bar places state and federal grant money into its Grants Fund and then redistributes these grant funds to legal aid organizations to accomplish such goals as providing legal assistance to the public to prevent homelessness or foreclosure. The program director for the State Bar’s Office of Access and Inclusion explained that the State Bar administers eight to 10 of these grants every year. The State Bar may use some portion of the grant money to pay the costs of administering these grants, but the State Bar cannot use this grant revenue for its other operations. Grants and interest from lawyer trust accounts make up the largest source of income. However, in general, the State Bar is restricted in how it can use these sources.

Revenue from the remaining category, licensing fees, is unrestricted: the State Bar may use these funds for its operations. Licensing fees ultimately support most of the State Bar’s non-grant related operations.

The State Bar uses its resources to accomplish its mission, which the text box presents. The State Bar’s responsibilities include regulating attorney education and conduct, creating greater access to the legal system, and ensuring the ethical and competent practice of law. Table 1 illustrates how the State Bar spent its revenue in 2023 to accomplish its mission. The State Bar spends most of its revenue to create greater access and inclusion for Californians in the legal system; revenue that supports this function includes the grant funds that the State Bar provides to legal aid organizations. The State Bar spends about 40 percent of its revenue on its licensing, regulation, and discipline function, which involves monitoring attorney licensing, misconduct, and legal education in California. The Office of Chief Trial Council (OCTC), the largest office within the State Bar, is responsible for the State Bar’s attorney discipline program; OCTC investigates allegations of misconduct against attorneys. In 2023 OCTC had almost 300 employees, which is nearly half of the State Bar’s workforce. Finally, the State Bar spends 2 percent or less of its revenue on the ethical and competent practice of law and on its own administrative infrastructure.

The State Bar’s Core Mission and Selected Responsibilities

Core Mission

State law establishes that “protection of the public … shall be the highest priority for the State Bar of California and the Board of Trustees in exercising their licensing, regulatory, and disciplinary functions. Whenever the protection of the public is inconsistent with other interests sought to be promoted, the protection of the public shall be paramount.”

Selected Responsibilities

- Licensure of attorneys in California.

- Enforcement of the Rules of Professional Conduct for attorneys.

- Discipline of attorneys who violate rules and laws.

- Administration of the California bar exam.

- Advances access to justice

- Promotes diversity and inclusion in the legal system

Source: State law and the State Bar’s website.

The State Bar administers its revenue through several different funds, such as the general, admissions, justice gap, and client security funds, as Table 2 shows. For example, the State Bar deposits much of the revenue from licensing fees into the general fund, which funds the OCTC. The State Bar also uses revenue from examination application fees, which it deposits into its admissions fund, to administer the bar exam in California. The State Bar uses optional fees paid by attorneys for the legislative activities fund, which spent $282,000 in 2023 on legislative activities.

The State Bar Administers the Attorney Discipline System

The OCTC receives, reviews, and analyzes complaints against attorneys; investigates allegations of unethical and unprofessional conduct against attorneys; and prosecutes attorneys in formal disciplinary hearings for violations of the State Bar Act or the Rules of Professional Conduct. OCTC opens around 15,000 discipline cases each year, and some of these cases eventually reach the State Bar Court. Composed of independent professional judges, the State Bar Court adjudicates formal disciplinary matters filed by the OCTC that may result in the imposition of discipline or a recommendation of discipline to the California Supreme Court.

The State Bar Is Responsible for Regulating Certain Law Schools in California

The State Bar monitors certain law schools and the education they provide. Law schools in California fall under one of the three categories: those approved and accredited by the Council of the American Bar Association Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar (ABA-approved schools); California Accredited Law Schools (CALS), which the State Bar accredits; and registered unaccredited law schools (unaccredited schools). Table 3 describes the three types of law schools and identifies the body responsible for regulating the schools in each category. The State Bar actively oversees CALS and unaccredited schools, which we describe later in the report and collectively refer to as California law schools. Pursuant to state law, ABA-approved schools are not subject to the State Bar’s oversight.

Statutorily Required Audits

Business and Professions Code section 6145 requires the State Bar to contract with the California State Auditor to conduct a performance audit of the State Bar’s operations every two years. For this audit, we reviewed the State Bar’s financial operations, including any cost-saving measures, its attorney discipline process and case backlog, and its oversight of California law schools.

Audit Results

The State Bar Must Continue to Achieve Cost Savings

The State Bar Has a Growing Backlog of Attorney Discipline Cases

The State Bar Must Continue to Achieve Cost Savings

Key Points

- In four of the past five years, the State Bar has spent more funds from its general fund than it has received.1

- The State Bar expects that the Legislature’s approval of an increase in the annual attorney licensing fees for 2025 will reduce, but not eliminate, its reliance on its general fund’s working capital balance.

- The State Bar has implemented cost-savings measures, but the impact of its most recent significant measures, including its efforts to reduce its workforce, remains uncertain.

Much of the State Bar’s Funds Have Restrictions on Their Use

The State Bar’s total financial net position—the amount by which an organization’s total assets exceed its total liabilities—was $227 million in 2023. However, there were legal restrictions on the State Bar’s use of $220 million of those assets. Generally, a fund’s restricted dollars can be used only within parameters set by the associated legal restrictions, as the text box explains. The State Bar administers 12 funds, all of which are restricted, except the general fund, as Table 4 shows.

A Fund’s Net Position Comprises Three Components

Net Investment in Capital Assets: Consists of capital assets, net of accumulated depreciation, amortization, and outstanding balances of borrowings that are attributable to the acquisition, construction, and improvement of those assets.

Restricted: Part of the net position that is subject to internal and external constraints imposed by grantors or by law through constitutional provisions or enabling legislation.

Unrestricted: Part of the net position that is available for day-to-day operations without constraints established by debt covenants, enabling legislation, or other legal requirements.

Source: The State Bar’s 2023 audited financial statements.

For example, the Legal Services Trust Fund, which receives revenue from the IOLTAs, experienced a significant increase in funds from 2022 to 2023 because of higher account balances and related interest yields. However, this revenue must be used only for the provision of legal services to indigent persons; it cannot be used on other State Bar functions, such as attorney discipline. Because revenues in the Legal Services Trust Fund have recently increased, so has the amount in grant awards that the State Bar has made to legal aid organizations. Specifically, the State Bar distributed $35 million in grant awards in 2022, $51 million in 2023, and reported a $95 million distribution of grant awards in 2024.

Given the restrictions on the use of nearly all of its funds, the State Bar has relied on its general fund to pay for its general operations, which it has been running at a deficit for most of the last several years. As Table 5 shows, the State Bar’s general fund’s expenditures have exceeded revenues in four of the last five years. The State Bar uses its general fund primarily for its attorney discipline functions as well as for communication and administration. Since the State Bar’s general fund expenditures were greater than the fund’s revenues in 2022 and 2023, the State Bar has had to rely on the fund’s working capital balance to continue paying for the services it provides. A fund’s working capital balance is the fund’s current assets minus its current liabilities.2

Table 6 shows that the working capital balance for six of the restricted funds, and for the unrestricted general fund, is falling. The general fund’s working capital balance at the end of 2023 was nearly $34 million, which improved, according to the State Bar, because of revenue from the sale of its San Francisco building. However, the State Bar projects this balance to decrease by around $15 million at the end of 2024.

A continued reliance on working capital could lead the State Bar to deplete its funds, and risk not being able to pay for its programs. We also highlighted this concern in our April 2023 audit of the State Bar.3 The State Bar explained in its 2024 request for a licensing fee increase that its strained financial condition is caused primarily by a lack of revenue from licensing fees and increasing costs.

The State Bar Expects Revenue From Increased Annual Licensing Fees to Reduce, but Not Eliminate, Its Reliance on the General Fund’s Working Capital in 2025

Relatively stagnant revenue for the State Bar’s general fund, combined with persistent and increasing costs, have led the general fund’s expenditures to consistently outpace its revenues. The State Bar’s primary source of general fund revenues comes from annual active and inactive attorney licensing fees, for which the Legislature sets maximum amounts. From 2013 to 2023, the number of active attorneys in California has increased only by approximately 10 percent, whereas the number of inactive attorneys has increased by 43 percent, as Table 7 shows. This trend leads to less State Bar revenue over time, given that active licensees pay far greater fees than their inactive counterparts. Additionally, the number of inactive attorneys who do not pay licensing fees—those age 70 or over—has increased by nearly 200 percent.

Meanwhile, the State Bar’s personnel costs increased by around $9 million from 2022 to 2023, or from $87 million to $96 million. This increase in costs results from a number of factors, including increases in OCTC staffing and union-negotiated salary adjustments. Increases to personnel costs are notable because these costs comprise the majority of general fund expenses.

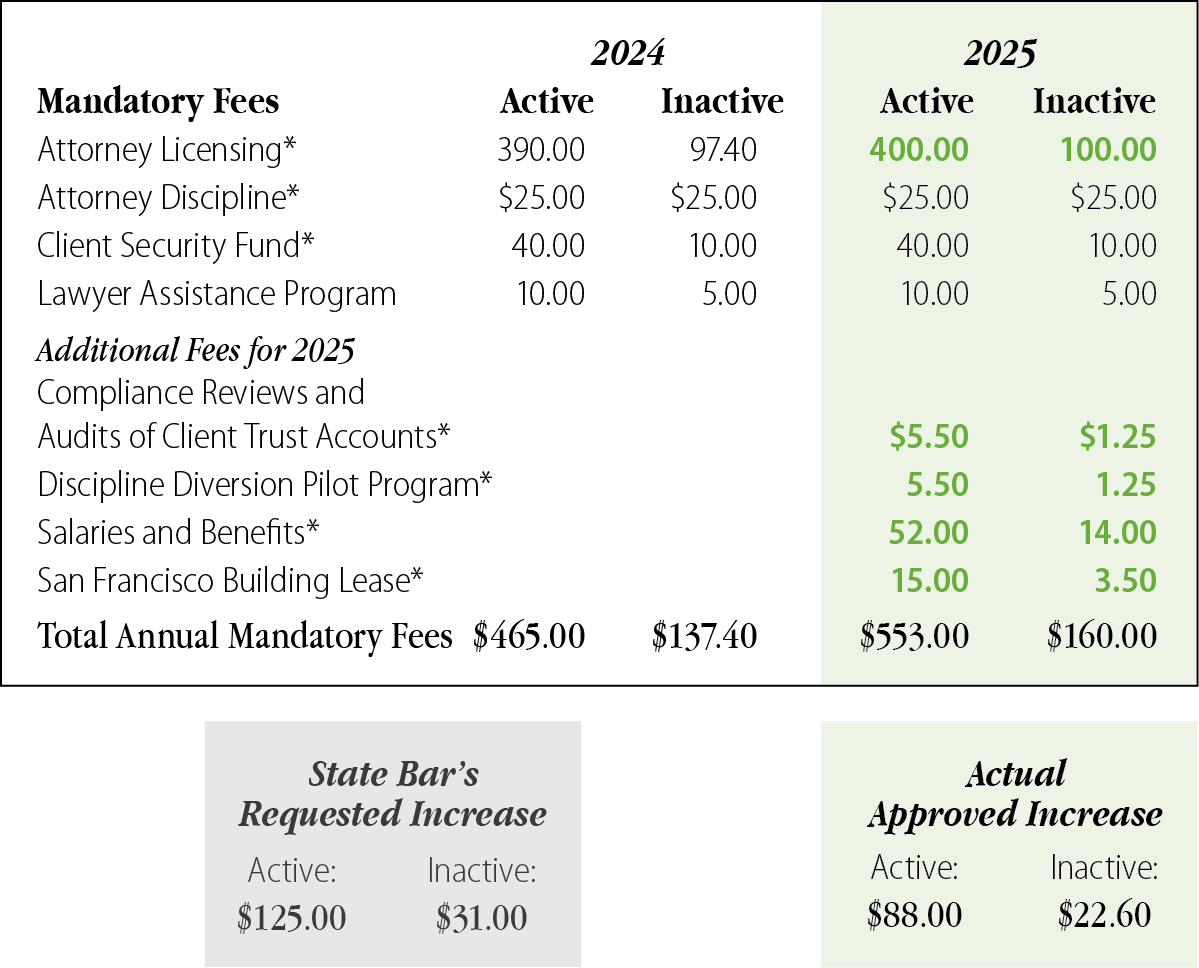

To address its strained financial position, the State Bar proposed to the Legislature in April 2024 to increase its active attorney licensing fee by $125 and increase its inactive attorney licensing fee by $31, as Figure 2 shows. Our office had also previously recommended in 2023 that the State Bar receive an increase in licensing fees.4 The Legislature ultimately approved an $88 increase in mandatory fees for active attorneys and a $22.60 increase for inactive attorneys’ fees, effective January 1, 2025.

Figure 2

The Legislature Approved Mandatory Fee Increases for Attorneys for 2025

Source: State law.

Note: This figure does not list voluntary fees that attorneys may choose to also pay the State Bar, such as a $5 fee per licensee for the State Bar’s lobbying activities, or fees that attorneys may choose not to pay, such as a $2 Elimination of Bias fee, which the Board would deduct from an attorney’s base licensing fee.

* The Legislature sets limits on these fees which the Board cannot exceed. The Board can choose to assess fees lower than these limits at its discretion.

This figure depicts a graphic listing the mandatory attorney licensing fees for the year 2024, their respective increases for the year 2025, and also additional fees that the Legislature approved for the year 2025. From left to right, the figure is organized with a list of all the current mandatory and additional fee types, their respective values for the year 2024, and finally their respective values for the year 2025. All the fees are divided into the two status types, specifically active attorney and inactive attorney. For example, the attorney licensing fee for 2025 for active attorneys is four hundred dollars. However, the attorney licensing fee for inactive attorneys for 2025 is one hundred dollars. Below the main graphic there are two additional boxes. One box indicates the State Bar’s requested fee increase for the year 2025. The second box indicates the increases the Legislature actually approved for the fees. Lastly, this figure does have footnotes with additional details below it.

We estimate that if the increased fees had been applied to 2023 attorney licensees, 2023 general fund revenue would have increased by about $17 million, as the text box shows. We performed this analysis to estimate the impact these fee increases may have using the most up to date financial information available. Although additional revenue should help alleviate some of the general fund deficit, the State Bar’s chief financial officer does not expect the increase to eliminate the State Bar’s need to spend from the general fund’s working capital balance in 2025. However, the State Bar’s cost-savings measures, which we discuss further in the next section, could help reduce expenses, which could alleviate the State Bar’s reliance on the general fund’s working capital.

2023 General Fund Revenue Would Have Increased by $17 Million if New Fees Had Been Applied

General fund revenue after 2025 fee increase per licensee:

2025 Active licensee fee increase:

$82.50

2025 Half rate (half-year) active licensee fee increase:

$41.25

2025 Inactive licensee fee increase:

$21.35

Number of active licensees in 2023:

200,920

Number of active licensees admitted to the State Bar after June 1st 2023 who pay half rate (half-year):

1,442

Number of inactive licensees:

37,008

[(82.50 * 200,920) + (41.25 * 1,442) + (21.35 * 37,008)] * 0.9831 =

$17,131,012

Source: State Bar licensee data and state law.

Note: The calculation above also assumes the 2025 attorney licensing fee collection rate to be the same as it was in 2023, specifically a rate of 98.31 percent.

The State Bar Has Implemented Effective Cost‑Savings Measures, but the Impact of Two Major Measures Remains Uncertain

In addition to requesting more revenue from the Legislature, the State Bar has pursued various cost-savings measures to help reduce its expenses. Some of these measures have yielded savings. For example, in both 2023 and 2024, as Tables 8 and 9 respectively describe, the State Bar reduced its costs associated with staff travel and State Bar meetings, compared to similar costs from 2019, before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, the State Bar sold its San Francisco headquarters building for $54 million and leased back some of the space in November 2023. The State Bar engaged the services of two real estate consulting agencies to evaluate the potential sale within the context of the San Francisco commercial real estate market. The consultants recommended that the State Bar accept the $54 million offer and sell its building especially given the unwise choice to continue to hold on to the building as an investment in a failing market, and the sale’s potential to generate a profit and positive cash flow. One consultant also recommended the sale because the State Bar did not have the funds to make the capital expenditures necessary to keep the building both functional and competitive in the marketplace. Therefore, after the State Bar paid its fees and outstanding debts related to the building, the influx of sale revenue allowed the State Bar to bolster its general fund’s working capital in 2023 by approximately $30 million, which it expects to use for 2024 general fund functions. Selling its San Francisco building also means that the State Bar is no longer responsible for maintaining the building, the cost of which was growing. In 2023 the State Bar estimated that the necessary capital improvements to the building would cost approximately $12 to $15 million by 2034. By selling the building, the State Bar is no longer financially responsible to make all these capital improvements.

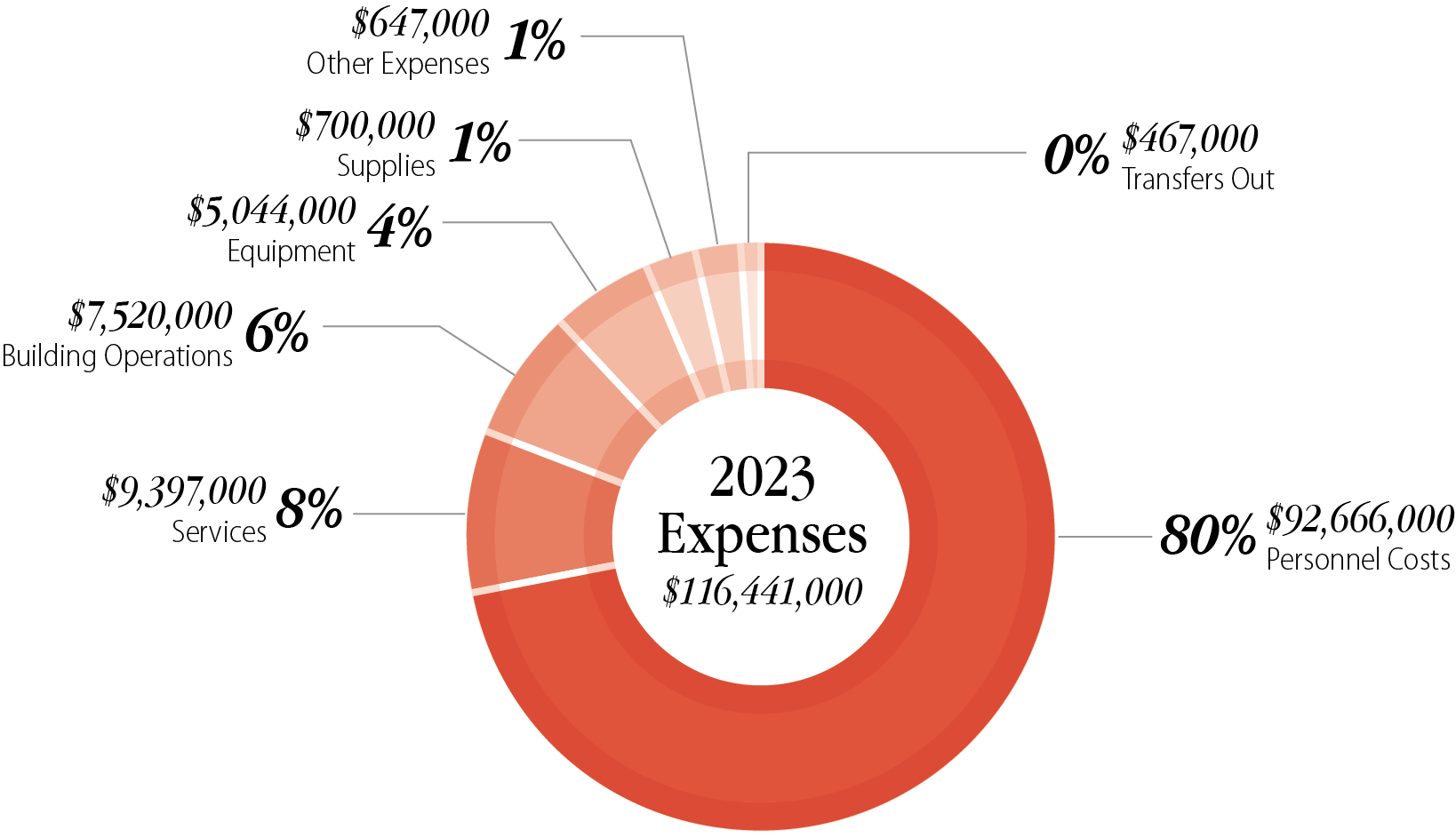

However, the State Bar has yet to realize the full impact of two other significant cost‑saving measures: one to reduce staff costs and one to reduce the cost of administering the California Bar Examination (bar exam). The State Bar is implementing an initiative to reduce the number of staff it employs through a reduction in workforce. Personnel costs were the State Bar’s largest general fund expense in 2023, as Figure 3 shows. In 2024 the Legislature required that the State Bar, which had an 8 percent staff vacancy rate in 2024, seek to achieve a 15 percent vacancy rate by April 2027. However, state law prohibits the State Bar from terminating employees solely for the purpose of meeting the target vacancy rate. Therefore, to respond to the Legislature’s mandated goal, the State Bar began to implement a reduction-in‑workforce measure in the fall of 2024. This measure provides incentives to persuade staff to separate voluntarily from the State Bar in exchange for certain benefits, such as 20 weeks’ severance pay and a potential two years of additional CalPERS service credit applied to an individual’s pension. The measure intends to reduce the State Bar’s staffing by around 50 full-time equivalent (FTE) positions, leading to potential savings in the millions. However, the exact number of FTEs is still unknown and therefore, so is the amount that the State Bar may save. Ultimately, the State Bar’s chief financial officer expects to start realizing cost-savings from the reduction‑in‑workforce measure in 2026.

Figure 3

The State Bar General Fund’s Largest Expense in 2023 Was Personnel Costs

Source: State Bar’s 2023 financial records.

Note: Dollar amounts rounded to the nearest thousand.

This figure is a pie chart that depicts that in the year 2023, the State Bar general fund had several expense categories. The total general fund expenses in the year 2023 was around one hundred sixteen million dollars, which is depicted in the center of the pie chart. Around this center, the pie is cut into pieces that correspond to the expenses. The larger the contribution, the greater the size of the pie a certain expense represents. The largest expense, representing eighty percent of the total pie, was personnel costs.

Most cost-savings in Tables 8 and 9 impact the general fund, but another large measure is associated only with the State Bar’s admissions fund. The admissions fund accounts for fees and expenses related to administering the bar exam and other requirements for the admission to the practice of law. In 2023 the admissions fund faced a deficit, and the State Bar used the fund’s working capital to pay for operations. The State Bar projects needing to use its admissions fund’s working capital again in 2024, similar to its use of the general fund’s working capital.

To address this admissions fund deficit, the State Bar proposed, and the Supreme Court approved, modifications to the bar exam. Previously, the State Bar had used the Multistate Bar Examination (MBE), purchased from the National Conference of Bar Examiners (NCBE), which required that the State Bar administer the MBE in State Bar-run facilities. This necessitated the State Bar’s procuring and renting of large testing locations, such as the Oakland Convention Center, for the exam. Starting with the February 2025 Bar Exam administration, the State Bar will replace the MBE with questions that another vendor developed for the State Bar and administer the exam remotely or in person. Early in 2024, the State Bar projected that this shift in the administration of the bar exam would save approximately $2 million per exam administration. However, as of January 2025, the State Bar has not yet finalized all of its contracts for its modified bar exam, and therefore the exact potential savings from this measure remain unknown.

The State Bar projects the modifications to the bar exam and the reduction in the number of staff to save millions of dollars. However, the total impact of the measures is unknown until they have been fully implemented. Nevertheless, it appears that the State Bar will need to rely not only on all of its cost-savings efforts but also on the projected increased revenue from attorney licensing fees to reduce or prevent its continued use of its general and admissions funds’ working capital. If the State Bar continues to rely on these diminishing funds and consequently remains in a strained financial position, the State Bar risks imperiling its mission of regulating attorney education and conduct, creating greater access to the legal system, and ensuring the ethical and competent practice of law.

The State Bar Has a Growing Backlog of Attorney Discipline Cases

Key Points

- In 2021 the Legislature tasked the State Bar with submitting for legislative consideration new timeliness standards for processing cases, which the State Bar has done; however, the State Bar has not yet been able to meet its proposed standards.

- The percentage of open cases in OCTC’s case backlog increased from 30 percent in 2021 to 36 percent in 2023 because of lengthy case processing times.

- Several new policy changes, including a pilot case diversion program (pilot diversion program) and expedited procedures, have reduced case processing times for cases closed in 2024 and may improve OCTC’s timely processing of cases going forward.

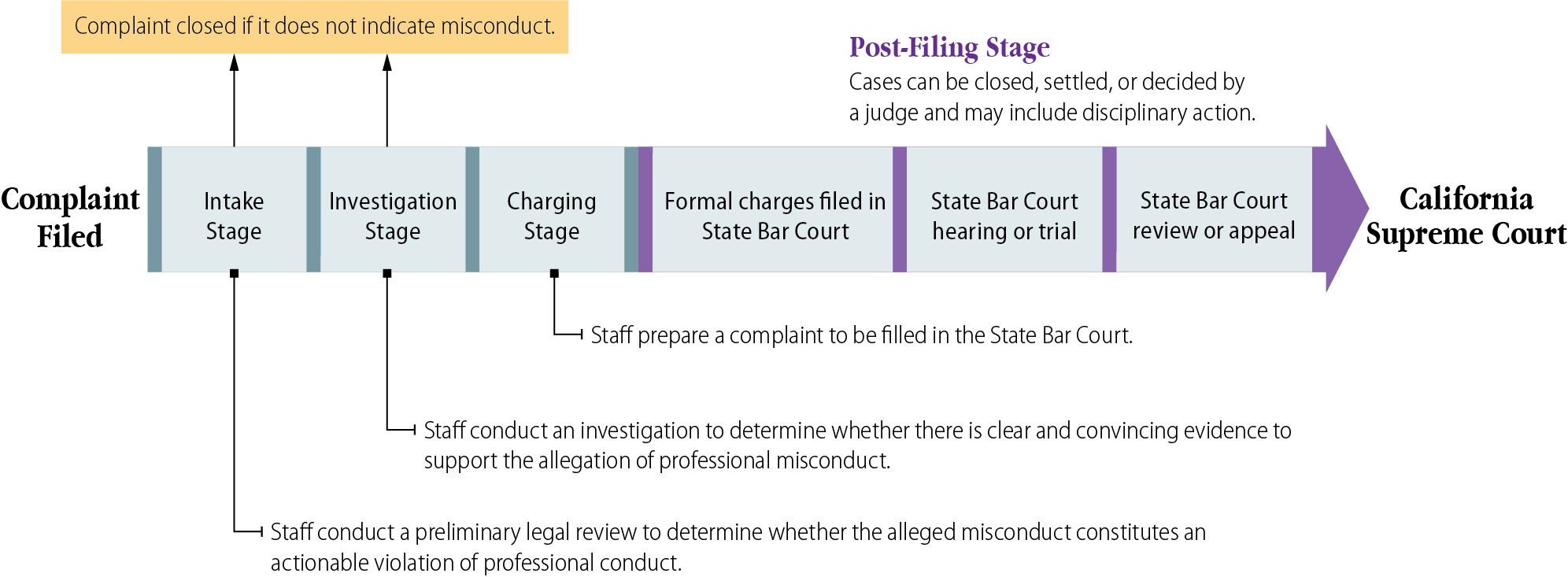

The State Bar Has Proposed New Standards for Case Processing Times

As we mention in the Introduction, the State Bar is responsible for public protection by regulating the profession and practice of law, enforcing rules of professional conduct for attorneys, and disciplining attorneys who violate rules and laws. OCTC receives, reviews, and analyzes complaints against attorneys; investigates allegations of attorneys’ unethical and unprofessional conduct; and prosecutes attorneys in formal disciplinary hearings for violations of the State Bar Act or the Rules of Professional Conduct. As Figure 4 shows, cases can be resolved during the case processing stages of intake, investigation, or charging. Each of these stages may contain backlogs of cases with processing times lengthier than the State Bar’s intended case processing time for that stage. We audited this case backlog in a 2021 report, and we discuss the impact of our previous audits specifically later in this report.5

Figure 4

The OCTC May Have Delays During Various Stages of Case Processing

Source: The State Bar’s Investigative Procedures Manual, the State Bar’s chief trial counsel, and the State Bar’s website.

This figure depicts how the State Bar’s OCTC generally processes a complaint against an attorney through the format of an arrow. The main large arrow is divided into the different case processing stages. The process starts with the filing of a complaint, and progresses through stages during which the case can be resolved and experience delays in its processing. If the case is not resolved in any of these stages, the case reaches its end at the California Supreme Court. The figure also provides more details on the process with additional smaller arrows extending from the figure’s main large arrow. For example, at the intake stage, there is a call-out which describes what actions OCTC staff perform during this stage.

In 2021 the Legislature mandated that the State Bar create standards for timeliness that reflect the goal of resolving attorney discipline cases in a timely, effective, and efficient manner and having small backlogs of attorney discipline cases. The State Bar subsequently proposed standards in 2022, but the State Bar noted that the Legislature has not yet codified these standards into law and the State Bar’s Board of Trustees has not formally adopted these standards. However the State Bar still strives to meet them. According to the State Bar, it did not intend the proposed standards to reflect timelines the State Bar was able to meet with its then-current staffing, but rather intended the standards to reflect the timelines that industry best practices recommend.

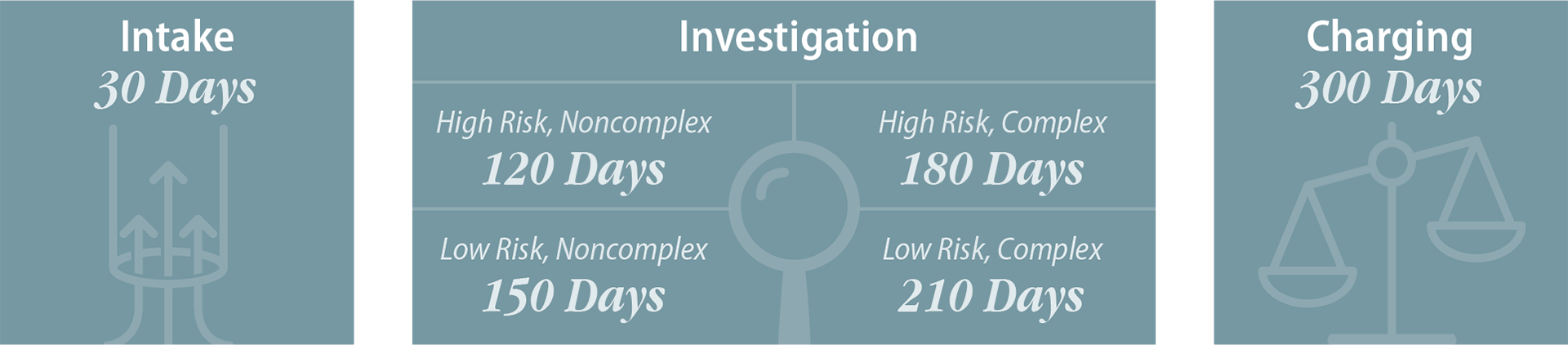

As Figure 5 shows, there are six proposed timeliness standards, depending on the stage of case processing and the type of case. OCTC considers cases complex if they involve multiple charges arising from multiple events, a large number of documents, or a lengthy investigation. Further, OCTC categorizes cases as high-risk if the attorney is alleged to have caused substantial harm or posed a risk of substantial harm, or if the attorney is the subject of multiple pending complaints that indicate the attorney may continue to engage in further misconduct. Accordingly, cases in the investigation stage of processing can be low-risk, noncomplex; high-risk, noncomplex; low-risk, complex; and high-risk, complex.

Figure 5

The State Bar Has Proposed Case Processing Timeliness Standards That Depend on the Case’s Stage and Type

Source: OCTC Case Processing Standards Proposal.

This figure is a graphic which depicts the proposed processing timeliness standards for different attorney discipline case stages and types. From left to right, the figure shows the standards for the intake, investigation, and charging stages. Within the investigation stage, which is depicted in the middle of the graphic, cases have proposed standards specific to its risk and complexity. For example, a high risk, noncomplex case at the investigation stage has a proposed case processing standard of one hundred twenty days. However, a low risk, complex case at the investigation stage has a proposed case processing standard of two hundred ten days.

OCTC’s Case Processing Times Have Increased, and It Cannot Meet the Proposed Standards with Its Current Staff Size

OCTC’s average case processing times remain higher than the proposed standards, leaving some complaints of alleged attorney misconduct unresolved for longer than OCTC considers best practice. Tables 10 and 11 show average case processing times for cases OCTC closed in 2021 and 2023, compared to the standards that OCTC proposed in 2022. We reviewed cases before and after the standards were proposed, and found that the average case age in 2021 was within the proposed standards for two of six case types but that none of the case ages were within the proposed standards for any case types in 2023. For cases requiring investigation, the investigation stage of case processing was the longest in both years. Although OCTC currently has 97 percent of its positions filled and the office itself comprises nearly half of the State Bar’s staff, it still reports lengthy case processing times. According to the State Bar, OCTC has not been able to meet the proposed standards because it needs additional staff. To determine the number of staff positions it would need to meet the standards and reduce backlogs, OCTC compiled a workforce analysis in April 2024. The analysis determined that the office would need $9.6 million over three years to fund an additional 57 FTE positions to meet the standards. The additional staff would help reduce high caseloads, allowing the current staff to process cases in the backlog and efficiently process incoming cases. When asked whether staff from other divisions within the State Bar might be reassigned to OCTC, the chief trial counsel explained that staff not qualified to process discipline cases would be ill-suited to the task.

The Legislature denied OCTC’s 2024 request to increase attorney licensing fees in 2025 by $15.25 so that OCTC could hire additional discipline staff to meet case processing standards, but the Legislature elected to expand the State Bar’s pilot diversion program, which we discuss later in the report. In addition, the legislative goal of a 15 percent vacancy rate that the State Bar seeks to achieve implies that either OCTC will have to decrease its workforce or the State Bar will need higher vacancy rates in other divisions to compensate for OCTC’s staff size. With an even smaller staff size, OCTC will likely have additional difficulty meeting case processing standards and therefore will not be able to resolve complaints of alleged attorney misconduct in a timely manner.

The Number of Cases in OCTC’s Backlog Has Grown Since 2021

Lengthy case processing times lead to backlogs of open cases. The State Bar also proposed backlog standards in 2022: it proposed that no more than 10 percent of cases should be in backlog. Under the proposed backlog standards, a case is considered in backlog if it is at 150 percent of the proposed standard case processing time by case type and processing stage. Table 12 shows that the percentage of the cases pending in backlog is increasing. At the end of 2023, almost 36 percent of the total pending cases were in backlog, increasing by 6 percentage points from the end of 2022. An increasing backlog may delay resolution for some cases and, to the extent those cases endanger the public, weaken public protection.

Our review found that cases may become backlogged for a variety of reasons. Some cases faced long delays because the State Bar attorney responsible for the case was reassigned and the newly assigned attorney was occupied with other cases. Some cases simply take a long time to investigate because of the need for more in‑depth collection of evidence, such as subpoenas or requests for bank statements. Finally, some cases appeared to remain in the backlog for a long time because OCTC received new evidence and reopened the case months or years after the case originally closed.

Although the Backlog Is Increasing, Three Recent Changes to OCTC’s Discipline Process Have Improved Case Processing Times

In July 2023, OCTC implemented a reorganization in which investigation and trial teams are specialized and assigned to a case according to the case’s complexity or its stage in case processing. Before this reorganization, a single attorney team in OCTC generally followed a case throughout its processing. Currently, however, intake staff will assign cases to vertical or horizontal teams. A horizontal team assumes responsibility for a case’s investigation, and then a separate trial team takes over if the case proceeds to court. A vertical team assumes responsibility for the case’s entire processing, from investigation through closing or trial. Vertical teams take cases that could be harmed if new staff takes over; these are cases that involve significantly complex legal issues or those in a series of cases that should be consolidated.

A second change in the way OCTC processes cases occurred in January 2024, when OCTC adopted a policy that its procedures for expedited investigation would become standard for most cases. For example, OCTC procedures no longer require an interview from the complaining witness unless staff agree that the interview is necessary. The new procedures also allow staff to send letters to complaint respondents by email instead of by physical mail. The removal of some previously standard procedural steps enables OCTC to create more efficient and effective investigation case processing stages.

Finally, the pilot diversion program implemented in October 2023 diverts certain cases to resources other than the attorney discipline system. The program targets cases against attorneys facing alleged, isolated instances of misconduct and who do not appear to present a significant risk of harm to the public. Attorneys whose alleged misconduct includes significant harm to the client, the public, or the administration of justice are not eligible for the pilot diversion program. Complaints that may be appropriate for the program include those against attorneys who failed to return files to clients or failed to disclose conflicts of interest without any evidence of client harm, as well as other instances of minor alleged misconduct. In most diverted cases, the respondents receive a letter specifying the conditions of the diversion. The attorney must sign the letter, accepting these conditions and acknowledging that failure to comply with the conditions will result in further investigation and charging. Staff monitor each diverted complaint to confirm that the attorney has met the diversion conditions. For example, OCTC intake staff may receive a case alleging that an attorney failed to comply with a minor court order. Intake staff would divert the case by sending the attorney a letter stating that the attorney must comply with the order and complete an educational course regarding court orders and the consequences of failure to comply. If the attorney completes the diversion conditions, the case would resolve without need for further investigation or disciplinary action. In the 2024 fee bill, the Legislature approved a $5.50 fee increase for active licensees to permanently fund the pilot diversion program. According to OCTC’s chief trial counsel, in early 2025 OCTC hopes to expand the eligibility of its diversion program, which may lead to more efficient closure of cases involving isolated misconduct.

To evaluate these three changes’ effect on case processing times, we compared the durations of cases opened before and after their implementation. Table 13 shows that cases opened after the adoption of the new policies close faster than cases opened before that time. For example, cases that OCTC closed after it implemented the new expedited investigation procedures were resolved during the investigation stage in only 81 days, yet a sample of cases opened before 2024 that OCTC resolved during the investigation stage had an average case age of 241 days. Further, OCTC closed cases during the charging stage in an average of 167 days after the team reorganization in July 2023, yet the average processing time of a sample of cases similarly resolved during the charging stage but opened before July 2023 was 581 days. Thus, OCTC resolved cases after July 2023 that it closed during the charging stage an average of almost 3.5 times faster than cases it opened before July 2023. Finally, Table 13 shows that for cases resolved during the investigation stage, OCTC closed diverted cases in an average of 124 days, half the processing time of the average of a sample of case before October 2023.

The implementation of the pilot diversion program may have slightly increased the average length of the intake stage because the program requires intake staff to monitor the diverted cases. However, all three changes decreased case processing times, indicating that processing times may decrease for cases closed in 2024 and that OCTC could make progress in meeting its case processing standards. These improvements may allow the State Bar to become a more effective regulator of attorney misconduct in the coming years.

The chief trial counsel for OCTC reported that OCTC plans to evaluate its changes to determine the efficacy of its discipline process before it considers making new requests to the Legislature. He stated that OCTC made a large series of changes, both to its organization and to its procedures, and is anticipating reductions in staff. Therefore, OCTC needs time to evaluate how effective and efficient these changes are before considering making such legislative proposals such as suggesting different case processing standards. Further, it is too soon to evaluate recidivism rates for attorneys affected by these changes. For example, in 2027 the State Bar expects to compile and submit a report on the expanded diversion program that the Legislature requested; the report will analyze the number of attorneys who have entered the expanded diversion program, their rate of re-offense, and the total reduction in caseload for the OCTC resulting from the program. Further, a Legislative assembly committee noted that although it rejected the State Bar’s request for additional staff for OCTC in 2024, it may reexamine the request in future years, depending on the expanded diversion program’s effects on OCTC’s workload and staffing needs.

Enrollment and Racial Diversity Have Increased in California Law Schools, but the State Bar’s Fees for Oversight of These Schools Lack Support

Key Points

- Although some schools have closed, overall enrollment at California Accredited Law Schools (CALS) and registered law schools that are unaccredited (unaccredited schools) in California—collectively referred to as California law schools—has increased, and so has the percentage of students of color.

- State law does not require the State Bar to provide resources to assist California law schools in accreditation and registration, and consequently the State Bar does not provide such resources. We spoke with deans and administrators at California law schools and found that schools generally had low interest in the State Bar providing these additional resources.

- The State Bar increased some of its oversight fees for law schools; however, it was unable to clearly explain the methodology it used for these changes.

The State Bar Regulates Two Types of Law Schools Located in California

As the Introduction explains, three types of law schools operate in California: unaccredited law schools registered with the State Bar; CALS, which are accredited by the State Bar’s Committee of Bar Examiners; and law schools approved and accredited by the American Bar Association (ABA-approved schools).6 Eligibility to practice law in California requires satisfying several listed conditions, including meeting minimum educational requirements and passing the California State bar exam. The minimum educational requirements can be met in several ways, including by acquiring a juris doctor (J.D.) degree or a bachelor of laws (LL.B.) degree, or by studying law for at least four years in a law school. Our review focuses on the two types of schools that the State Bar regulates: unaccredited schools and CALS. As part of its regulatory responsibility, the State Bar requires that California law school students receive a requisite number of hours of instruction and schools maintain a sound program of legal education. Table 14 shows the number of schools in each type and the number of students enrolled in 2023.

Although Some Small Schools Have Closed, Law School Enrollment and the Percentage of Students of Color Have Increased From 2013 Through 2023

Enrollment numbers have increased at California law schools.7 Specifically, total California law school student enrollment at unaccredited schools and CALS has increased from 4,580 students in 2013 to 5,184 students in 2023—a growth of 13 percent. We noted that CALS student enrollment has increased by 112 percent from 2013 through 2023, growing from 2,147 students to 4,556. Conversely, enrollment in unaccredited schools decreased from 2013 to 2023, from 2,433 students to 628 students—a decline of 74 percent. The decrease can be attributed in part to the transition of three formerly unaccredited schools to CALS.

Further, the overall law school student population in California has become more racially diverse, with CALS and unaccredited schools comprising a larger percentage of students of color than ABA-approved schools. From 2013 through 2023, the percentage of students of color increased in each type of law school, as Table 15 shows. For example, in 2013, students of color made up 41 percent of all students enrolled in CALS. In 2023 students of color comprised 57 percent of all students enrolled in CALS.

School closures did not affect the overall population of students enrolled in California law schools. We noted that 19 California law schools closed from 2013 through 2023.8 Of these schools, 18 were unaccredited and one was a CALS. The 19 schools that closed had a combined student enrollment of 293 students in their last year of operation or available data, with an average school size of 18 students. For perspective, the total number of students in all unaccredited and CALS schools in 2023 was 5,184. Further, 13 of the 19 schools that closed did so voluntarily. The schools cited various reasons for their closures, such as low enrollment, COVID-19 pandemic-related challenges, and a change in ownership. The six schools that closed involuntarily lost registration because of noncompliance with various State Bar rules and guidelines. These include requirements pertaining to deans and faculty, such as having faculty that devote adequate time to administration, instruction, and student counseling. In addition, we reviewed schools that lost accreditation from 2013 through 2023 and found that four CALS lost accreditation. These schools lost accreditation primarily because of non-compliance with State Bar rules and guidelines for CALS, such as the requirement to maintain minimum bar passage rates. These schools are still operating as unaccredited law schools; therefore, their students continue to be a part of the overall population of students enrolled in California law schools.

The State Bar Is Not Required to Provide Resources to Schools to Aid in Accreditation or Increase Student Diversity, and Schools Say They Do Not Need Resources

As part of our review, we assessed whether the State Bar dedicates sufficient resources to assist law schools with accreditation and with enrolling students with diverse backgrounds. State law requires the State Bar to approve, regulate, and oversee degree-granting California law schools, but it does not prescribe that the State Bar create or distribute resources to assist schools seeking accreditation. Further, there is no requirement that the State Bar should directly promote enrollment of students to California law schools. We reviewed the various forms of support that the State Bar provided to schools, such as inspection preparation materials and templates that schools can use to prepare the reports they must submit annually to the State Bar. We found that although these materials can assist schools in complying with State Bar rules and guidelines, the materials do not help schools acquire State Bar accreditation. Further, although the State Bar requires CALS to create and maintain diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) policies, the director of the State Bar’s Office of Admissions (admissions office) stated that the State Bar has not created resources to aid schools in obtaining accreditation or increasing diverse student enrollment because it has not identified a need for such resources. She explained that by offering alternative legal pathways the State Bar attracts diverse applicants. Further, she added that the admissions office created its rules and guidelines with DEI as a guiding principle.

Law schools generally told us they did not need additional assistance from the State Bar. We spoke with 20 current and two former deans and administrators of California law schools. Representatives of only three of the 22 schools we contacted said they wanted the State Bar to provide resources to help the schools comply with the State Bar’s rules and guidelines. Only four of the 22 schools found it difficult to comply with the State Bar’s rules, citing frequent changes to reporting templates, rules for distance learning, and general interpretations of the rules and guidelines. Only one of the schools we spoke with expressed interest in the State Bar providing resources to encourage diverse law student enrollment. Finally, five deans at both unaccredited schools and CALS said they would like more information regarding the State Bar’s rules and use of school oversight fees. We discuss fee setting further in the next section.

The State Bar Lacked a Clear Rationale for Increasing Its Fees for Overseeing California Law Schools

The State Bar assesses and sets fees for California law schools to fund services associated with its responsibility to regulate those schools. These services include accreditation, registration, and inspection, collectively referred to as oversight. For example, the State Bar requires California law schools to submit an annual report that details their compliance with certain laws and State Bar rules and regulations. The State Bar charges each of the law schools a fee that is due at the time of report submission (annual fee). Generally, fees related to oversight help fund the personnel costs of staff in the State Bar’s Admissions Office or external consultants who perform oversight work. In 2023 nearly 60 percent of the State Bar’s oversight expenses were for personnel costs, which funded two full-time State Bar employees, and about 40 percent were for indirect costs, which are costs associated with items such as information technology and facilities.

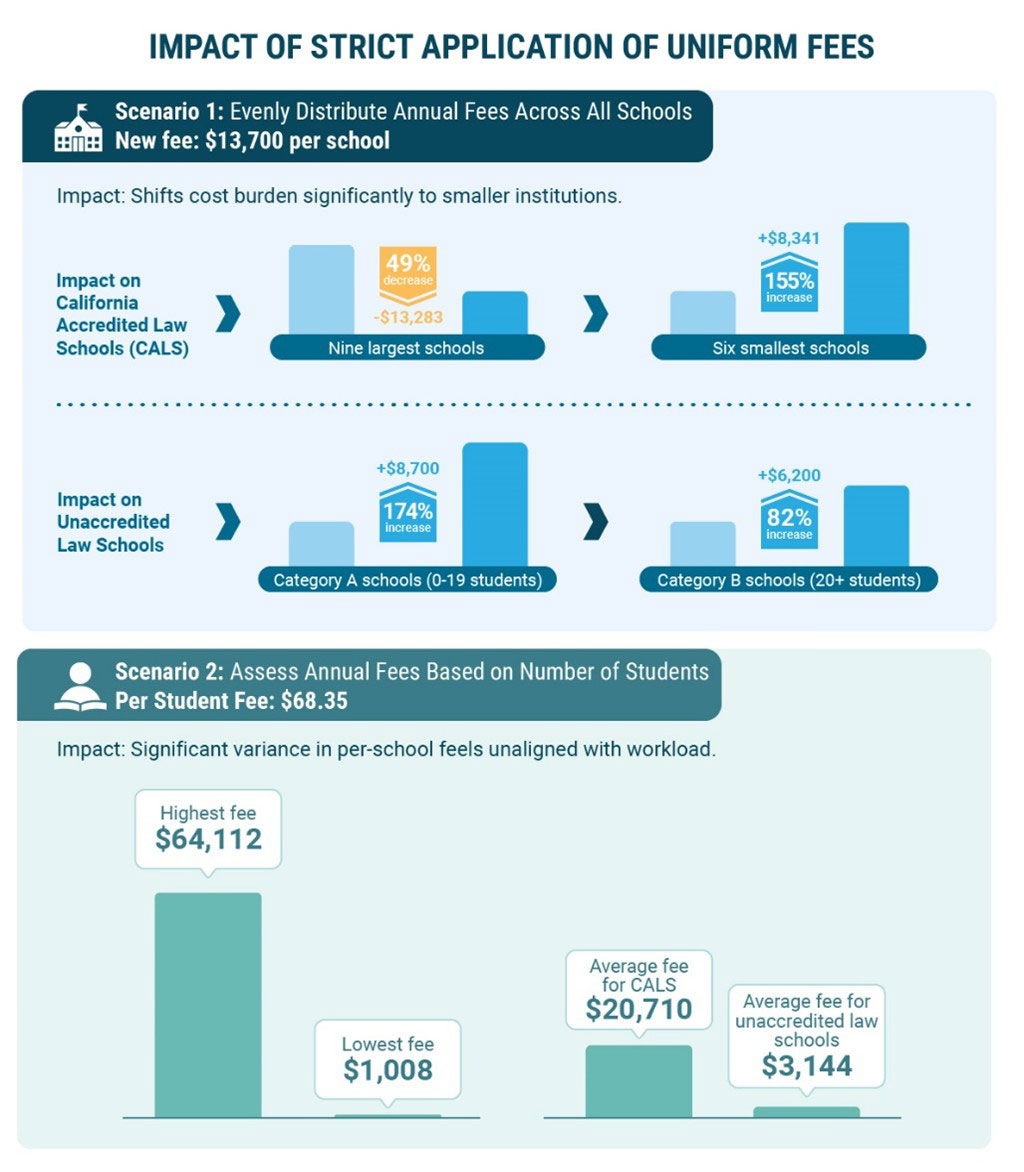

In recent years, the State Bar’s expenses for law school oversight have been much greater than its revenue from the fees it charges for the related work, so the State Bar increased some of those fees for the first time since 2018. For example, as we show in Table 16, the State Bar’s expenses for law school oversight in 2023 were nearly $320,000 greater than its revenue. To address this fiscal imbalance, the State Bar’s Board of Trustees (Board) approved oversight fee increases and changes to the fee structures for unaccredited law schools in 2023. The Board separately approved fee increases and fee structure changes for CALS in 2024.

These fee amounts for law schools differ according to the school’s accreditation status and the size of its student body. The State Bar calculates its annual fee amount for a CALS by the number of students enrolled in the school, whereas the State Bar imposes a flat fee on an unaccredited school of $5,000, $7,500, or $10,000, depending on the size of the school’s student body. Further, schools pay an inspection fee in the year they undergo an inspection.9 For CALS, the inspection fee is an initial deposit of $37,500.10 For unaccredited schools, the State Bar bases its inspection fee on student body size. Table 17 provides some examples of these fees and their recent changes. We expected the State Bar to have performed an analysis of the actual cost of each service it provides and to have assessed the related fee accordingly so that it could explain its disparate fees and align with financial best practices. Specifically, the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) recommends that when government entities set fees, they should calculate the full cost of providing a service in order to provide a basis for setting the charge or fee.

However, the State Bar’s methodology for setting its fees for services and for imposing the recent fee increases did not demonstrate whether the fees specifically cover the cost of the State Bar’s actual oversight efforts. For example, in 2018 the State Bar charged California Desert Trial Academy College of Law, an unaccredited school, an annual fee of $1,090. In 2023 the State Bar’s annual fee for a school that size increased to $7,500, as Table 17 shows. Additionally, the State Bar increased the annual fee for Trinity Law School, a CALS, from $2,170 in 2018 to nearly $24,000. The State Bar now determines its annual fee for CALS by the number of students enrolled, multiplied by a standard of around $60 per student enrolled for that year. The State Bar did not explain whether it calculated the significant increases for each of the example schools according to the State Bar’s actual efforts for its annual report services for each school or school type.

For CALS, the State Bar in 2023 proposed both a flat annual fee and also options for a tiered approach to the fees based on student body size, similar to its fee structure for unaccredited schools. However, in response to feedback from the law schools indicating that they would pass on to their students the State Bar’s increased fees for schools, the State Bar decreased the proposed fee increase amount. During this process, the State Bar also changed its method for setting that fee, now calculating its annual fee for CALS according to the number of students enrolled. However, the State Bar kept its tiered fee structure for unaccredited schools. In doing so, the State Bar did not explain whether the $60 assessment per enrolled student is indeed the cost of its services per student, nor did it explain why it did not also use the same method to change its fees for unaccredited schools.

Consequently, the State Bar’s methodology for setting its fees for services does not explain why fees for the same services differ among schools according to accreditation status or student body size. For example, as Table 17 shows, the State Bar charges a base inspection fee of $30,000 to Taft Law School, an unaccredited school with 93 students. However, for the same service, the State Bar charges a base inspection fee of $37,500 to Empire College School of Law, a CALS with 48 students.

When discussing the oversight process and the associated fees for services, the State Bar’s chief of mission advancement and accountability division explained that regulating CALS is relatively similar to regulating unaccredited law schools. However, the chief could not provide a clear reason to explain why the Board approved differing oversight fees, other than the different oversight fees could be the possible result of longstanding practice. Further, the State Bar’s director of admissions explained that the State Bar recognizes that the cost of many services is not directly proportional to the size of a law school’s student body. The State Bar’s rationale for not providing a clear basis for its fees, such as the rationale GFOA recommends, is that the State Bar relies on fees from all schools in the aggregate to fund its oversight services as a whole and not on a per-school basis. If this is true, and regulating both types of California law schools is indeed similar, it remains unclear why any school would pay a fee different from the fee another school pays for the same State Bar service.

Other Areas We Reviewed

The State Bar Has Fully Implemented Most of Our Previous Audit Recommendations

We reviewed the previous audit recommendations that our office made to the State Bar in reports released in 2021, 2022, and 2023. We found that of the 10 recommendations we had previously determined the State Bar had not yet fully implemented, the State Bar had fully implemented nine as of December 2024.11 The State Bar intends to complete its implementation of the remaining recommendation in the future.

Our previous recommendations addressed several different State Bar functions and processes, some of which we discuss earlier in this report. In our April 2023 report, The State Bar of California: It Will Need a Mandatory Licensing Fee Increase, Report 2022-031, we recommended that the State Bar review the fees it charges for the services it delivers and increase those fees as necessary. In our April 2022 report, The State Bar of California’s Attorney Discipline Process: Weak Policies Limit Its Ability to Protect the Public From Attorney Misconduct, Report 2022-030, we made several recommendations to the State Bar to update and better monitor policies and procedures associated with its management of attorney discipline cases. Finally, in our April 2021 report, The State Bar of California: It Is Not Effectively Managing Its System for Investigating and Disciplining Attorneys Who Abuse the Public Trust, Report 2020-030, we made several recommendations to the State Bar to address its attorney case discipline process and the related case backlog. As Table 18 shows, we found that the State Bar has fully implemented most of our recommendations, and we continue to recommend that the State Bar work to implement the remaining recommendation. The State Bar’s most recent responses to these previous report recommendations, and our assessment of its implementation of them, can be found at https://www.auditor.ca.gov/.

Recommendations

Legislature

To ensure that the State Bar has time to implement the expanded diversion program and gather data on its effectiveness, the Legislature should wait until the State Bar reports in 2027 on how its recent changes to the OCTC’s operations will affect case processing timelines before the Legislature codifies the OCTC’s proposed standards.

The State Bar

To improve its financial position, the State Bar should complete its implementation of the modified bar exam and especially its reduction-in-workforce measure, which should help it achieve the Legislature’s mandated vacancy rate goal and achieve savings.

To measure the effectiveness of changes to OCTC’s operations and support potential future requests for OCTC staffing, the State Bar should adopt the proposed case processing standards by August 2025 as benchmarks against which to measure OCTC’s progress in shortening timelines and reducing backlog.

To ensure consistency in its setting of law school oversight fees, the State Bar should by August 2026 reexamine its methodology for determining all fees for CALS and for unaccredited schools and set supportable fees for all law schools. In developing the fees, the State Bar should conduct a fiscal analysis to ensure that the fee amounts charged to law schools reflect the State Bar’s actual cost of its oversight, unless it determines that doing so would limit the public’s access to the services.

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards and under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by Government Code section 8543 et seq. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on the audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

February 27, 2025

Staff:

John Lewis, CIA, Audit Principal

Aaron Fellner, Senior Auditor

Myra Farooqi

Alexis Hankins

Vlada Lipkind

Kate Monahan

Legal Counsel:

Heather Kendrick

Ethan Turner

Appendix

Scope and Methodology

We conducted this audit pursuant to the audit requirements in Business and Professions Code section 6145, which requires the State Auditor to conduct a performance audit of the State Bar’s operations. For this audit, we assessed the State Bar’s budgets and fees, the management of its attorney discipline system’s case backlog, and the provision of law school regulation. We also reviewed the status of our recommendations to the State Bar from previous audits. The table lists the objectives and the methods we used to address them. Unless otherwise stated in the table or elsewhere in the report, statements and conclusions about items selected for review should not be projected to the population.

Assessment of Data Reliability

The U.S. Government Accountability Office, whose standards we are statutorily obligated to follow, requires us to assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of computer-processed information we use to support our findings, conclusions, or recommendations. In performing this audit, we relied on various data sources. To determine the percentage of attorneys who paid their licensing fees, we used the State Bar’s KOALA Attorney Tracking System (tracking system). We verified the completeness of the data by collecting the total number of billed attorneys and attorneys who paid their fees from the collection rate analysis and comparing that information to the tracking system’s data for 2022 and 2023. We also reviewed the accuracy of the data by testing a random sample of the bar numbers (IDs) of 30 attorneys who were in the paid dataset by reviewing documentation that verifies these attorneys submitted payment for their licensing fees in 2022 and 2023. Using this testing, we determined that these data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our audit.

We also relied on the State Bar’s attorney discipline data to determine case processing lengths and backlogs from 2021 through 2024. To assess the reliability of this data, we performed accuracy testing on a random sample of 29 cases by tracing key data elements to supporting documentation. We found nine errors in the case opened dates and four errors in the case closed dates. As a result, we determined that these data were unreliable, but we found that there is no alternative source for these data. Although this determination may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

Response

State Bar of California

February 5, 2025

Grant Parks, CPA

California State Auditor

621 Capitol Mall, Suite 1200

Sacramento, CA 95814

RE: State Bar of California Response to Audit Report No. 2024-030

Dear Mr. Parks:

We appreciate the State Auditor’s careful review of the State Bar’s financial position, discipline case processing trends, and oversight of California accredited and registered law schools, and are pleased to agree with each of the recommendations outlined in the report. We also welcome the recognition of the proactive measures we have taken to ensure the State Bar’s financial health, as well as the progress that has been made during the initial implementation of the Office of Chief Trial Counsel’s (OCTC) diversion program.

Formal responses to each recommendation follow. Where relevant, contextual information is added to the “support” position associated with each.

State Bar Responses to Audit Recommendations

1. Recommendation: To ensure the State Bar has time to implement the diversion program and gather data on its effectiveness, the Legislature should wait until the State Bar reports in 2027 on how its recent changes to the OCTC’s operations will effect timelines before it codifies the OCTC’s proposed standards.

Response: The State Bar agrees with the recommendation.

2. Recommendation: To address its uncertain financial position, the State Bar should complete its implementation of the modified bar exam and especially its reduction in force measure, which should help it achieve the Legislature’s mandated vacancy rate.

Response: The State Bar agrees with the recommendation.

3. Recommendation: To measure the effectiveness of changes to OCTC’s operations and support potential future requests for OCTC staffing, the State Bar should adopt the proposed case processing standards as benchmarks against which to measure OCTC’s progress in shortening timelines and reducing backlog by August 2025.

Response: The State Bar agrees with the recommendation.

① While the State Bar appreciates the State Auditor’s recognition that case-processing times improved after OCTC’s adoption of its diversion pilot program and other revised case processing procedures, it has been unable to duplicate the analysis underlying the dramatic improvements of between 48 percent and 67 percent in investigation time and between 71 percent and 87 percent in charging time attributed to these procedural changes in Table 13 of the report. The improvements in case processing times reflected in Table 13 exceed our understanding of the overall expected and actual results of OCTC’s diversion program and other revised case processing procedures. We caution our stakeholders against expecting such accelerated case processing times for all matters going forward.

4. Recommendation: To ensure consistency in its assessment of law school oversight fees, by August 2026 the State Bar should reexamine its methodology for determining all fees for CALS and for unaccredited schools, and adopt reasonable fees for all law schools In developing the fees, the State Bar should conduct a fiscal analysis to ensure the fee amounts charged to law schools reflect the State Bar’s actual cost of its oversight, unless it determines that doing so would limit the public’s access to the services.

Response: The State Bar agrees with the recommendation.

While the State Bar agrees with the recommendation, it is important to underscore that, despite recent fee increases, the law school regulation program continues to operate at a deficit, as confirmed by the audit report. The State Bar Admissions Fund has long subsidized this shortfall and will continue to do so even in light of the recent law school fee increases outlined in the report.

② The current fee structure was developed pursuant to a process involving detailed financial analyses, stakeholder engagement, and a policy decision by the Board of Trustees not to pursue full cost recovery due to the significant impact such an approach would have on smaller institutions. While recognizing that there is room for improvement, the State Bar believes that this structure balances the financial impact on students and schools while accounting for the reality that subsidy is necessary to ensure broad accessibility and that regulatory costs are not directly proportional to student enrollment. The tiered fee structure for unaccredited law schools minimizes the burden on small schools while ensuring that each law school meaningfully contributes to covering regulatory expenses. This approach aligns with the prevailing approach in this space, namely the American Bar Association’s accreditation fee structure, which is tiered based on school size, which is tiered based on school size.

② As reflected in the table below, a strict application of the same fee to all schools or assessing fees on a strictly per student basis could exacerbate fee disparities between institutions.

Lastly, we applaud the increase in law student diversity highlighted in the report. We would be remiss in not pointing out however, that diverse enrollment does not necessarily translate to representative matriculation and bar pass rates. As highlighted in our recent Profile of California Law Schools report, significant disparities in student outcomes remain a challenge at schools with diverse initial student populations: nearly 70 percent of Black students experience 1L attrition at unaccredited law schools, for example. Of those who matriculate, only 9 percent of unaccredited law school students, across all demographic groups, pass the California Bar Exam.

In closing, we would like to thank the audit team that conducted the review. To our knowledge this is the first time that the State Bar admissions function has been the subject of inquiry. We look forward to future engagement on this aspect of our work in the coming years, and to implementing the recommendations outlined in the report in furtherance of our public protection mission.

Brandon N. Stallings

Chair, Board of Trustees

Leah T. Wilson

Executive Director, The State Bar of California

Comment

California State Auditor’s Comments on the Response From the State Bar of California

To provide clarity and perspective, we are commenting on the response to our audit from the State Bar. The numbers below correspond to the numbers we have placed in the margin of its response.

① Although the State Bar indicated that it was unable to duplicate the results of our analysis that we present in Table 13, it shared with us the results of its analysis and we found that they were indeed similar to our own. In fact, in some instances, the results of the State Bar’s own analysis yielded even greater efficiencies than our analysis. Furthermore, because our methodology used a large random selection of cases to compare against the cases that were affected by the State Bar’s recent policy changes, the State Bar would be unlikely to precisely duplicate the results of our analysis.