2024-801 Local High Risk Program

The State Auditor Is Removing Its High-Risk Designation From Four Cities and Retaining the Designation for Three Others

Published: December 19, 2024Report Number: 2024-801

December 19, 2024

Audit 2024‑801

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

This audit report updates the status of the cities of Blythe, El Cerrito, Lindsay, Lynwood, Montebello, San Gabriel, and West Covina as high‑risk entities as part of our office’s high‑risk local government agency audit program. Our prior audits of these cities identified areas of high-risk related to the cities’ financial conditions, financial stability, and oversight of city contracts, among other issues. For this statutory audit, we reviewed the extent to which each city has addressed recommendations from prior audits, assessed trends in the cities’ financial conditions, and determined whether we should continue to designate any of these cities as high-risk local government agencies.

This report concludes that the cities of Blythe, El Cerrito, Lynwood, and San Gabriel have taken satisfactory corrective action and addressed key deficiencies identified in our prior reports. Therefore, we are removing their high-risk designation. In accordance with the laws relating to the local high-risk program, we may subsequently reevaluate the high-risk designations of the cities of Blythe, El Cerrito, Lynwood, and San Gabriel if situations change and these cities appear to be at risk of not being able to meet their financial obligations or provide efficient and effective services to the public, among other concerns.

Although the cities of Lindsay, Montebello, and West Covina have taken steps to improve their overall financial health, we are not removing the high-risk designation from those cities at this time. We will continue to monitor the cities and the actions they take to address the areas of high risk we have identified. When the cities’ actions result in sufficient progress toward resolving or mitigating such risks, we will remove their high-risk designation.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Prior Relevant Reports Issued by the California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| ACFR | Annual Comprehensive Financial Report |

| ARPA | American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 |

| GFOA | Government Finance Officers Association |

| OPEB | Other Post-Employment Benefits |

Introduction

The California State Auditor’s High‑Risk Local Government Agency Audit Program

State law authorizes the California State Auditor (State Auditor) to establish a local high‑risk program to assess, audit, and ultimately issue reports about local government agencies that we designate as high risk for potential waste, fraud, abuse, or mismanagement, or that we identify have major challenges associated with their economy, efficiency, or effectiveness. State law requires that all audits we conduct as part of this program initially be approved by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee. If we designate an agency as high risk, that agency must submit to us a corrective action plan that addresses the conditions that caused us to make the designation. In this report, we refer to those conditions as high‑risk areas. An agency’s corrective action plan is due no later than 60 days after the publication of an audit that concluded the agency was high risk, and agencies must then submit periodic updates on the status of that plan every six months thereafter.

We remove the high‑risk designation when an agency has taken satisfactory corrective action. To assess local agencies’ progress in addressing their high‑risk areas, we may conduct assessments of the agency’s progress at six‑month intervals that correspond with the corrective action plan updates that the local agencies provide. Also, state law requires that we issue an audit report on high-risk local government entities every three years, unless we have removed them from the high‑risk program. For this audit, we reviewed the seven cities listed in the text box to determine the extent to which each city has addressed prior audit recommendations, assess trends in the city’s financial condition, and determine whether we should continue to identify any of these cities as high‑risk local government agencies.

Cities Included in This 2024 Local High‑Risk Follow-Up

- Blythe (Riverside County)

- El Cerrito (Contra Costa County)

- Lindsay (Tulare County)

- Lynwood (Los Angeles County)

- Montebello (Los Angeles County)

- San Gabriel (Los Angeles County)

- West Covina (Los Angeles County)

Overall this audit concludes that the cities of Blythe, El Cerrito, Lynwood, and San Gabriel have taken satisfactory corrective action and addressed key deficiencies we identified in our prior reports. Therefore, we are removing their high‑risk designation. In accordance with the laws relating to the local high‑risk program, we may subsequently reevaluate whether Blythe, El Cerrito, Lynwood, or San Gabriel should be identified as high risk if situations change and these cities appear to be at risk of not being able to meet their financial obligations or provide efficient and effective services to the public, among other concerns. Although Lindsay, Montebello, and West Covina have taken steps to improve their overall financial health, we are not removing the high‑risk designation from those cities at this time. Throughout this report, we have made additional recommendations to those cities whenever the circumstances of their risk areas meant that our previous recommended corrective actions were no longer relevant or sufficient. In cases when our existing recommendations from previous audits continue to be applicable to these cities’ circumstances, we do not make any new recommendations.

General Areas of Importance to This Local High‑Risk Audit

Although this audit addresses the specific risks pertaining to seven cities, several topic areas are applicable to more than one city. We present background information about each of these areas below.

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021

In response to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA) appropriated federal funds to help provide state, local, and tribal governments with the resources needed to mitigate the fiscal effects. As Table 1 shows, each of the seven cities we reviewed as part of this audit received such funding, which we refer to as ARPA funding. Federal guidance on the regulations that govern ARPA funding prohibits recipients from using ARPA funding for debt service or to replenish financial reserves. However, the regulations permit recipients to claim a standard allowance of up to $10 million in ARPA funding as replacement for lost revenue. In effect, by claiming the lost revenue allowance, recipients could spend their ARPA funding on a wide range of activities and choose to save the revenue that they would have otherwise spent on those activities. To avoid reverting ARPA funding back to the federal government, recipients must spend the entirety of their ARPA funding by December 31, 2026.

Proposition 218

Proposition 218—a constitutional amendment adopted by the voters in 1996 to limit the ability of local governments to impose taxes, assessments, charges, and fees based on property ownership—prohibits the use of revenue from fees and charges for any purpose other than that for which the fee or charge was imposed. It also establishes that revenue from the fees and charges may not exceed the costs of providing such services. Proposition 218 helps ensure that the proposed levy amount is proportionate to the cost of the related governmental activity and prohibits local governments from using fee revenue on unrelated expenses.

Guidance on Reserves for General Purpose Governments

According to the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA), it is essential that governments maintain adequate levels of general fund balances to mitigate current and future risks such as revenue shortfalls and unanticipated expenditures. As a best practice, the GFOA recommends that governments, regardless of size, maintain an unrestricted budgetary fund balance in their general fund of no less than two months of regular general fund operating revenues or regular general fund operating expenditures. We use the term unrestricted when discussing funding over which the government has discretion (i.e., no constraint) over how the funds can be spent. For the purpose of our report, we refer to unrestricted general fund balances as general fund reserves.

Other Post‑Employment Benefits

City governments can provide compensation packages to employees who have completed their active service. The Governmental Accounting Standards Board defines Other Post‑Employment Benefits (OPEB) as retirement health benefits provided separately from or through a pension plan, as well as other benefits such as life insurance or long‑term care benefits as long as the city provided those benefits separately from a pension plan. OPEB benefits may include medical, dental, vision, hearing, and other health‑related benefits paid subsequent to the termination of employment. According to the GFOA, OPEB and defined benefit pension plans can represent a significant challenge in terms of their funding and long‑term stability. To ensure that these benefits are sustainable over the long term, the GFOA recommends governments evaluate key items specifically related to OPEB, including the structure of benefits offered.

Agencies’ Proposed Corrective Action

Lindsay and West Covina acknowledged our current assessment of their progress in addressing their respective risk areas. Montebello generally concurred with our recommendations for addressing the risk areas that we determined were not fully addressed, but the city disputed some of our statements and conclusions about those areas. Although none of these cities submitted a corrective action plan as part of its response, we look forward to receiving the plans by February 2025.

Audit Results

The City of Montebello Has Not Kept Its Costs Below Its Revenue and Thus Remains a High‑Risk Entity

The City of El Cerrito Has Taken Corrective Action to Address Its Risk Areas, and the State Auditor Is Removing Its High‑Risk Designation

| RISK AREAS AS REPORTED IN MARCH 2021 | STATE AUDITOR’S CURRENT ASSESSMENT OF EL CERRITO’S PROGRESS IN ADDRESSING THE RISK AREA* | |

|---|---|---|

| El Cerrito’s Failure to Manage Its Spending Resulted in Depletion of Its General Fund | ||

| 1 | Continual diminishing of financial reserves through overspending | Fully Addressed |

| 2 | Ineffective budget development and monitoring practices | Fully Addressed |

| Without a More Coordinated Effort, El Cerrito’s Financial Condition Will Continue to Deteriorate | ||

| 3 | Lack of formal financial recovery plan | Fully Addressed |

| 4 | Insufficient reductions in ongoing costs | Partially Addressed |

| 5 | Missed opportunities to increase revenue | Fully Addressed |

* In accordance with state law, we used our professional judgment to assess the city’s progress in addressing each of the risk areas in the table. We determined whether the steps the city took and the overall conditions relevant to each risk area meant that the city fully or partially addressed the risk areas, or whether substantial action relevant to the risk area was still pending. We explain the statuses identified in this table in more detail below.

Fully addressed: The city has taken sufficient action to address the risk area when we consider its effort in combination with the related conditions at the time of this audit.

Partially addressed: The city has taken positive action to address the risk area, but its effort is incomplete when we consider it in combination with the related conditions at the time of this audit.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #1

Continual Diminishing of Financial Reserves Through Overspending

Status: We conclude that El Cerrito’s recent fiscal performance and increased general fund reserves demonstrate that it has fully addressed this risk area.

In our March 2021 audit, we reported El Cerrito was at high risk of being unable to meet its financial obligations. In the fiscal years preceding that audit, the city had consistently spent more than its general fund revenue and was relying on short‑term loans to cover its financial obligations. However, in recent years, El Cerrito has made a concerted effort to control its finances and has stabilized the condition of its general fund. Further, in our March 2023 assessment, we reported that because of its improved financial position, the city discontinued its practice of short‑term loan borrowing in fiscal year 2022–23. El Cerrito’s adopted budgets for fiscal years 2023–24 through 2025–26 assume that the city will meet its debt obligations in those years without the use of short‑term loans.

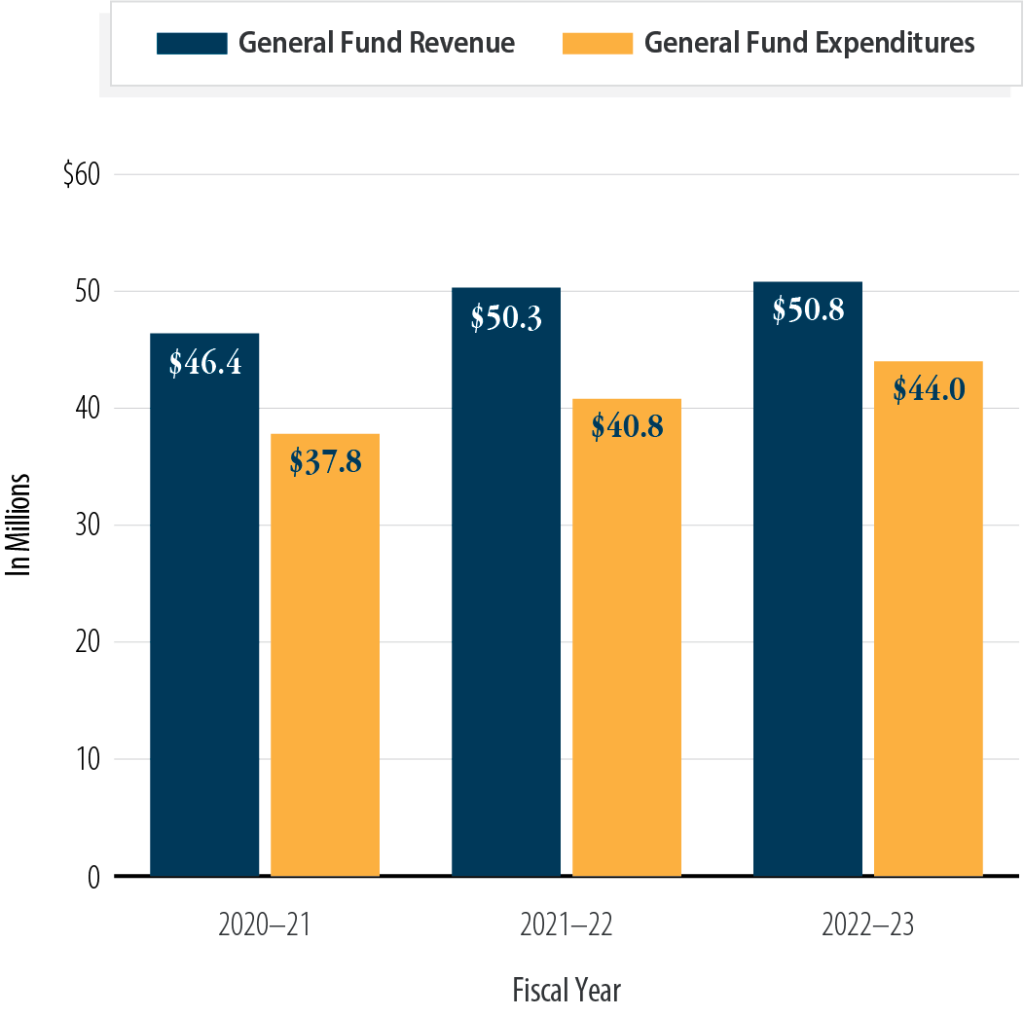

Figure 1 shows that from fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23, the city’s general fund revenues exceeded its expenditures, which assisted the city in growing its general fund reserves to $23 million by the end of fiscal year 2022–23, which is an amount equal to about half of its general fund expenditures for that year. This amount surpasses the minimum of two months of unrestricted reserves the GFOA advises governments to maintain. According to the city’s fourth quarter budget update for fiscal year 2023–24, El Cerrito expects its revenue to nearly cover its expenditures, with the shortfall being about $186,000. This amount represents less than 1 percent of the city’s expected total expenditures for that fiscal year. According to its projections for future fiscal years, which extend as far as fiscal year 2028–29, the city expects that it may occasionally need to rely on its reserves starting in fiscal year 2026–27. However, the amount it expects to need in its reserves is proportionately small—less than 2 percent of the budgeted expenditures. Finally, the city also benefited in recent years from its receipt of about $6.1 million in ARPA funding. As of March 2024, the city reported having spent all of this funding and having used it for a variety of general government purposes, such as the provision of public safety services and on administrative facilities.

Figure 1

The City of El Cerrito’s General Fund Expenditures Have Been Consistently Less Than Its Revenue in Recent Years

Source: El Cerrito’s ACFRs.

Note: We calculated revenue by combining the revenue and transfers into the general fund in each fiscal year. We calculated expenditures by combining the expenditures and transfers out of the general fund in each fiscal year. The city did not have any material amounts of other financing sources or uses flowing in or out of its general fund in these three fiscal years.

Figure 1, a bar chart that compares El Cerrito’s general fund revenue to its general fund expenditures for fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23. For fiscal year 2020–21, the bar chart shows that El Cerrito’s general fund revenue was $46.4 million compared to $37.8 million in general fund expenditures. For fiscal year 2021–22, the bar chart shows that El Cerrito’s general fund revenue was $50.3 million compared to $40.8 million in general fund expenditures. For fiscal year 2022–23, the bar chart shows that El Cerrito’s general fund revenue was $50.8 million compared to $44.0 million in general fund expenditures. The bar chart includes a note stating that we calculated revenue by combining the revenue and transfers into the general fund in each fiscal year. We calculated expenditures by combining the expenditures and transfers out of the general fund in each fiscal year. The city did not have any material amounts of other financing sources or uses flowing in or out of its general fund in these three fiscal years. The data for this bar chart comes from El Cerrito’s Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports.

The city has several strategies planned that could help it minimize reliance on its general fund reserves. For example, according to its biennial budget for fiscal years 2024–25 and 2025–26, the city intends to develop a citywide cost allocation plan and comprehensive fee study. Doing so will better ensure that the city is distributing costs across its funds in the most appropriate way, potentially lessening the burden on its general fund, and that it maximizes cost recovery from the service fees it charges. The city intends to follow those studies with a service delivery study to ensure that it delivers services in the best and most efficient ways. The city estimates that it will complete the cost allocation plan in December 2024 and the fee study in February 2025. The city’s budget states its intent to complete the service delivery study sometime in fiscal year 2025–26. El Cerrito’s city manager stated that the city will use the data collected from these studies to make informed and sustainable decisions during the next two fiscal years that will improve the city’s ability to balance its future budgets and mitigate reliance on general fund reserves.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #2

Ineffective Budget Development and Monitoring Practices

Status: In March 2022, we concluded that El Cerrito had fully addressed this risk area by improving its budget process and monitoring departmental spending.

In our March 2022 assessment, we reported that El Cerrito improved its budgeting processes to provide meaningful information for making fiscally sound decisions. The city improved its quarterly budget updates to the city council by providing revenue and expenditure amounts by department and comparing those amounts to both its budget and prior‑year expenditures. This additional level of detail can assist city council members in identifying when a particular department may be overspending. The city has also improved the information presented in its adopted budgets. Its fiscal year 2021–22 budget included a five‑year forecast with a comparison to the prior four‑year period. Finally, its adopted fiscal years 2024–25 and 2025–26 biennial budget includes a forecast through fiscal year 2028–29 and a comparison of the prior two fiscal years.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #3

Lack of Formal Financial Recovery Plan

Status: In September 2022, we concluded that El Cerrito had fully addressed this risk area by issuing its Fiscal Recovery and Sustainability Plan.

In our September 2022 assessment, we noted that El Cerrito issued its Fiscal Recovery and Sustainability Plan in August 2022 and concluded that the city addressed this risk area. The city organized the plan by the actions it planned to take, and it identified a lead staff member, a target date of completion, and an annual fiscal impact for nearly all of the actions. Further, the city divided the plan into actions the city council had approved in August 2020, such as the elimination of the assistant to the city manager position; actions the city identified that it could still take; and actions based on recommendations from our 2021 audit. The plan provides a number of objectives for the city to improve its financial condition and information that will allow the city council and the public to hold the city accountable.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #4

Insufficient Reductions in Ongoing Costs

Status: We conclude that El Cerrito has partially addressed this risk area by making an effort to reduce personnel costs and completing a citywide salary study. Nonetheless, the city will need to be attentive to costs in the future because the recent salary study could generate pressure to increase personnel costs.

Through a variety of methods, El Cerrito has controlled its spending and has kept the growth of its expenditures below the growth of its revenue. Since fiscal year 2019–20, general fund revenue has grown 27 percent, and expenditures have grown only 10 percent. By freezing salaries, eliminating positions, and instituting controls for departmental spending, the city has limited ongoing costs. For example, the city did not implement cost‑of‑living increases for its management and confidential employees in fiscal years 2020–21 and 2021–22. In addition, in fiscal year 2021–22, the city eliminated seven positions in its police department, some of which had become vacant because of retirements and resignations. By fiscal year 2022–23, the city had decreased the police department’s personnel costs by 3.4 percent from their fiscal year 2020–21 levels. However, the city reported that the actions it took to reduce the budget and staffing had a detrimental impact on the department, which the city asserts experienced high vacancies in 2022. According to its fiscal year 2022–23 budget, in fiscal year 2021–22 the city employed individuals in 28 of 37 authorized sworn positions. To address the police union’s concerns, the city agreed to adjustments in salary ranges and pay differentials according to educational experience. As a result, although costs declined in fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23, the city budgeted to increase the police department’s personnel costs by 18 percent in fiscal year 2023–24.

To sustain its financial health, the city will need to carefully approach any future compensation increases. In response to our 2021 audit, the city commissioned a salary study. In February 2024, the city received the results of that study, which identified that the city compensated some of its positions—including some public safety positions—at less than the market median when compared to similar positions at 18 other entities. The study found that, overall, the city’s base salaries were approximately 8 percent less than the market median. Further, the city’s total compensation, which includes salary and benefits, was about 2 percent less than the market median. Although the study did not explicitly recommend that the city raise compensation for its employees, it did provide suggested approaches the city could take to adjust its compensation. In March 2024, the city reported to our office that it plans to implement the study’s recommendations over time, and as resources allow, through bargaining and other phased adjustments, and it expects that doing so will assist the city in recruiting, motivating, and retaining competent staff, including its public safety staff.

The city’s fiscal years 2024–25 and 2025–26 biennial budget notes that the city was engaged in negotiations with several bargaining groups at the time it developed the budget. Therefore, the city may need to amend its budget if the negotiated compensation amounts exceed its budgeted costs. According to the adopted budget, the city plans to increase personnel costs by 6.4 percent in fiscal year 2024–25 and by 5 percent in fiscal year 2025–26. Overall, El Cerrito’s personnel costs represented 73 percent of the city’s budgeted general fund expenditures for fiscal year 2024–25. However, despite the upcoming challenge the city faces in determining how much to compensate its employees, the city has appeared to have maintained fiscal discipline in the past few years, which indicates that it is committed to overall fiscal health when deciding such matters. Finally, the city may also find that the cost allocation plan, fee study, and service delivery study that we mention earlier present it the opportunity to save additional amounts in its ongoing expenditures, which the city could then use to balance any increases in personnel expenditures.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #5

Missed Opportunities to Increase Revenue

Status: In September 2023, we concluded that the city had fully addressed this risk area by completing a cost recovery analysis for its recreational services.

In our September 2023 assessment, we concluded that the city addressed this risk area. In particular, we noted that El Cerrito continued to subsidize its senior services with budgeted revenue for fiscal year 2023–24 covering 80 percent of the cost of those services—about $88,000 according to the city’s budget documents. In its 2023 update to our office, the city reported that full cost recovery would not provide services at an acceptable cost that contributes to the quality of life of all people in El Cerrito. Because the city has made a policy decision to subsidize these costs and the amount of the subsidy is relatively small, we considered the risk area addressed.

The City of Lynwood Has Made Significant Progress in Addressing Its Risk Areas, and the State Auditor Is Removing Its High‑Risk Designation

| RISK AREAS AS REPORTED IN DECEMBER 2018 AND SEPTEMBER 2021 | STATE AUDITOR’S CURRENT ASSESSMENT OF LYNWOOD’S PROGRESS IN ADDRESSING THE RISK AREA* | |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Financial Management Hinders Lynwood’s Fiscal Stability | ||

| 1 | Ongoing budget deficits and uncertain financial future | Fully Addressed |

| 2 | Inadequate budgeting practices | Fully Addressed |

| 3 | Questionable salary increases | Fully Addressed |

| Violations of State Law, Weak Oversight, and Policy Breaches Make Lynwood Susceptible to Fraud and Waste | ||

| 4 | Violations of state law regarding the use of water and sewer funds | Fully Addressed |

| 5 | Poor contract administration | Fully Addressed |

| 6 | Inadequate controls over its financial operations | Fully Addressed |

| Ineffective Organizational Management Diminishes Lynwood’s Ability to Provide Public Services | ||

| 7 | Lack of strategic plan | Partially Addressed |

| 8 | Inability to effectively measure staffing needs | Pending |

| 9 | Significant turnover in key positions and no plan for identifying future leadership | Partially Addressed |

* In accordance with state law, we used our professional judgment to assess the city’s progress in addressing each of the risk areas in the table. We determined whether the steps the city took and the overall conditions relevant to each risk area meant that the city fully or partially addressed the risk areas, or whether substantial action relevant to the risk area was still pending. We explain the statuses identified in this table in more detail below.

Fully addressed: The city has taken sufficient action to address the risk area when we consider its effort in combination with the related conditions at the time of this audit.

Partially addressed: The city has taken positive action to address the risk area, but its effort is incomplete when we consider it in combination with the related conditions at the time of this audit.

Pending: The city has not taken substantial action to address the risk area and, at the time of this audit, the conditions that created high risk for the city continue to exist.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #1

Ongoing Budget Deficits and Uncertain Financial Future

Status: We conclude that Lynwood’s fiscal improvement and increased general fund balance demonstrate that it has fully addressed this risk area.

In our September 2021 follow‑up audit, we determined that Lynwood did not always keep its general fund reserves at recommended levels, and we recommended that the city revise its reserve policy to align with GFOA best practices to facilitate ongoing financial stability and guard against short‑term revenue shortfalls.

Since that audit, the city has increased its general fund reserves and has maintained its expenditures below revenues. Figure 2 shows that the city’s revenue has increased over a three fiscal year period. By the end of fiscal year 2022–23, the city’s general fund reserves had grown to $47.5 million—more than its revenue for that year and substantially surpassing the minimum of two months of unrestricted reserves the GFOA advises governments to maintain. A significant factor in the advances that the city made in its general fund reserves was the city’s receipt of a total of $24.4 million in ARPA funding across fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23. The city was able to use this funding in place of its regular general fund revenue, thus allowing it to retain that regular revenue to be available for other needs.

Figure 2

The City of Lynwood Kept General Fund Expenditures Below Revenue for Three Straight Fiscal Years

Source: Lynwood’s ACFRs.

Note: We calculated revenue by combining the revenue and transfers into the general fund in each fiscal year. This figure does not include other financing sources flowing into the general fund in the amount of $2 million in fiscal year 2021–22 that resulted from a one‑time sale of assets. We calculated expenditures by combining the expenditures and transfers out of the general fund in each fiscal year.

Figure 2, a bar chart that compares Lynwood’s general fund revenue to its general fund expenditures for fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23. For fiscal year 2020–21, the bar chart shows that Lynwood’s general fund revenue was $41.3 million compared to $36.1 million in general fund expenditures. For fiscal year 2021–22, the bar chart shows that Lynwood’s general fund revenue was $47.9 million compared to $30.0 million in general fund expenditures. For fiscal year 2022–23, the bar chart shows that Lynwood’s general fund revenue was $45.3 million compared to $29.5 million in general fund expenditures. The bar chart includes a note stating that we calculated revenue by combining the revenue and transfers into the general fund in each fiscal year. The figure does not include other financing sources flowing into the general fund in the amount of $2 million in fiscal year 2021–22 that resulted from a one-time sale of assets. We calculated expenditures by combining the expenditures and transfers out of the general fund in each fiscal year. The data for this bar chart comes from Lynwood’s Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports.

In addition, in October 2024, Lynwood adopted a reserve policy that aligns with GFOA guidance. Because of the city’s recent history of keeping spending below revenues and its improved general fund reserves, we determined that the city has mitigated this risk area.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #2

Inadequate Budgeting Practices

Status: We conclude that Lynwood has fully addressed this risk area regarding its budgeting practices by adopting meaningful practices and formalizing those practices as required actions in its policies.

In our September 2021 follow‑up audit, we raised concerns that Lynwood’s budgeting process posed a risk to the city because it was incomplete and not done in a timely manner. As a result, we recommended that the city meet the specified timeframes in its budget calendar in future budget cycles. The city council’s recent actions show that Lynwood is now adopting budgets on time. The city council approved the city’s biennial budget for fiscal years 2023–24 and 2024–25 before the start of that period, which is the only full budget the city prepared since the conclusion of our last audit. The city council also approved the mid‑cycle update to that budget before the start of fiscal year 2024–25.

We also determined in our September 2021 audit that the city should follow its existing policy and provide quarterly reports to its city council that compare budgeted to actual general fund revenue and expenditures. Further, we recommended that the city align its policy on quarterly reporting with GFOA best practices for budget monitoring. For example, the city’s policy should require the city’s staff to present an analysis of the reasons for budget deviations. For fiscal year 2023–24, the city provided the city council with quarterly reports, each of which presented the budgeted general fund revenue and expenditures to actual general fund revenue and expenditures and explained the variances between these amounts. The city adopted a policy in October 2024 that formalized the expectation that it continue its practice of providing quarterly reports to the city council.

Finally, our 2021 audit noted that the city had not adopted a policy to produce multi‑year projections of its revenues and expenditures. Subsequently, the city included a multi‑year projection of its general fund revenues and expenditures as part of its biennial budget for fiscal years 2023–24 and 2024–25. The city also formalized its practice of creating multi‑year projections in its October 2024 policy update.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #3

Questionable Salary Increases

Status: We conclude that Lynwood has fully addressed this risk area by assessing its compensation against other cities and presenting reasons for proposed increases to its city council.

In our September 2021 follow‑up audit, we reported that Lynwood was not complying with its salary‑setting policy. Specifically, in the three cases we reviewed, Lynwood did not maintain documentation showing it had compared its proposed salaries to those in benchmark cities. In two of these cases it did not present the justification for the proposed salaries to the city council.

During this audit, we found that the city was comparing salaries for certain city positions to those of other cities and that it presented justification for a set of proposed salaries to its city council. We reviewed the city’s 2023 salary survey, which evaluated salaries for 13 city positions, comparing the salaries for those positions to the salaries for similar positions when they existed at 10 nearby cities. The city’s director of human resources and risk management explained that the city conducted the salary survey during its negotiations with the bargaining unit that represented the employees in those positions. At the conclusion of negotiations, the city presented to the city council the proposed salaries for those positions and explained that the salaries resulted from the agreement the city had reached with the bargaining unit. Because Lynwood is documenting its salary‑setting analysis and has shared its rationale for raising salaries with the city council, there exists better assurance that it is setting competitive and reasonable salaries in a transparent manner.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #4

Violations of State Law Regarding the Use of Water and Sewer Funds

Status: We conclude that Lynwood has fully addressed this risk area through the elimination of lease payments from its utility authority and the use of a cost allocation plan that identifies water and sewer costs.

In our September 2021 follow‑up audit, we identified risks associated with the city making inappropriate transfers to its general fund through a lease arrangement it established for its water and sewer infrastructure. Specifically, we noted that in fiscal year 2019–20 the city established a $1 million lease payment to its general fund from the utility funds, an amount for which the city could not provide justification. Consequently, we recommended that the city dissolve the Lynwood Utility Authority (utility authority), the entity with which it made the lease arrangement, and discontinue making any lease payments. In response, Lynwood declined to dissolve the utility authority and stated that the utility authority has issued revenue bonds. We agree that the city’s concerns about dissolution are valid, insofar as the dissolution of the utility authority could potentially represent a breach of contract with the bond holders. Further, we noted that the city has planned to stop making the lease payments to the general fund. The city’s fiscal year 2024–25 budget shows no plans to transfer the $1 million lease payment to the general fund. Accordingly, we consider this element of the area of risk resolved.

The city recently addressed a concern regarding reimbursement for overhead costs from its water and sewer funds to its general fund. In our September 2021 report, we noted that the city had not approved updated cost allocation plans that it could have used to support the amount it transferred from its water and sewer funds to its general fund for overhead charges. We concluded that the city was at risk for either over‑ or under‑reimbursing the general fund. In April 2024, the city received the results of another cost allocation study, which identifies the city’s overhead costs that the general fund may recover from the water and sewer funds. The city incorporated those adjusted overhead costs into its revised fiscal year 2024–25 budget. These adjustments resulted in an overall reduction in payments of approximately $80,000 from the water fund and an increase in payments of about $69,000 from the sewer fund.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #5

Poor Contract Administration

Status: We conclude that Lynwood’s steps to strengthen its contract administration demonstrate that it has fully addressed this risk area.

In our September 2021 follow‑up audit, we found that Lynwood had not addressed a recommendation we had made in the 2018 audit that it amend its municipal code to require the city council to provide adequate written justification when bypassing competitive bidding through a supermajority vote and to define when such an action is appropriate. We also observed that the city had exempted contracts for garbage collection from competitive bidding, which we found jeopardized the city’s ability to obtain the best value for its residents and community. In October 2022, the city council approved updates to the sections of its municipal code addressing procurement procedures. The municipal code no longer includes provisions for the city council to use a supermajority vote to exempt a purchase from competitive bidding requirements or exemption from competitive bidding for garbage collection contracts. Further, unless the purchase is a type preapproved in the city’s municipal code for sole source procurement, the city’s procurement policy requires it to use a competitive sourcing process whenever a product or service is available from more than one source and is valued at more than $5,000. In August 2023, the city provided training to its staff on its updated requirements for contracting and purchasing. The training addressed the municipal code sections the city amended in October 2022 and amendments to its contracting and purchasing policy.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #6

Inadequate Controls Over Its Financial Operations

Status: In a previous audit, we concluded the city fully addressed external audit findings regarding control weaknesses in its financial operations.

In our September 2021 follow‑up audit, we determined that the city had fully addressed this risk area and addressed an external auditor’s findings regarding controls over its financial operations.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #7

Lack of Strategic Plan

Status: We conclude that Lynwood has partially addressed its risk related to strategic planning.

Although the city engaged a consultant to help it to develop strategic priorities, that work did not include the development of specific strategies and outcomes to accompany the strategic priorities. Instead, the consultant’s report indicated that the city’s executive management team would meet later to identify those elements of a strategic plan. The city’s director of human resources and risk management confirmed that the city has not developed a full strategic plan, and he indicated that the city would work beginning in 2025 to select a vendor to assist it in developing a strategic plan.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #8

Inability to Effectively Measure Staffing Needs

Status: We conclude that Lynwood has not addressed its risk related to its inability to effectively measure staffing needs.

In our September 2021 follow‑up audit, we found that the city could not effectively determine whether its staffing levels were sufficient and appropriate to efficiently address the city’s priorities for the services that it provides. We identified that, according to the GFOA, strategic planning establishes logical connections between spending and an entity’s goals and that the focus of strategic planning should be on aligning resources to bridge the gap between present conditions and the envisioned future. Therefore, strategic planning is a critical element to a city’s ability to identify the appropriate staff levels it needs to achieve its goals. Accordingly, it will be important for the city to reassess its staffing after it develops a strategic plan. The city’s director of human resources and risk management stated that the city will work to align its staffing to achieve its goals within the strategic plan the city plans to develop, but any changes in staffing levels or the allocation of staff will be subject to the city’s budget constraints and availability of funding.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #9

Significant Turnover in Key Positions and No Plan for Identifying Future Leadership

Status: We conclude that Lynwood has partially addressed its risk related to significant turnover in key positions and a lack of a plan for identifying future leaders.

In April 2022, in response to our previous audits of the city, the Lynwood city council adopted the city’s succession plan, which has the purpose of identifying and developing internal staff with the potential to fill the city’s key leadership positions. Among other actions, the plan calls for regular and recurring gap analyses to identify projected openings in positions that require certain skill sets, leadership and professional training opportunities, and job shadowing to provide opportunities for aspiring employees to develop an understanding of the positions into which they wish to advance.

Lynwood has begun implementing its plan. The city provided us with its September 2024 gap analysis identifying the city positions that face the greatest risk of employee retirements, and the director of human resources and risk management indicated that the city would amend its succession plan policy to include provisions for conducting the gap analysis annually. He also described his plan to coordinate with the city manager to develop a policy that would require department managers to document the processes they use to make key decisions to provide continuity among leadership, and he anticipated the city would complete that policy by the end of March 2025. In our September 2021 audit, we found that the city had implemented a leadership academy, and the human resources director described leadership training sessions from 2023 that the city was providing to designated staff members as part of that academy. However, he also confirmed that the city has not yet started its job shadowing program. As the city continues to plan for retirements from key positions, it should implement the remaining elements of its succession plan, such as the job shadowing program, as well as the policy changes described by the director of human resources and risk management.

The City of San Gabriel Has Made Substantial Progress in Rebuilding Its Reserves and Addressing Other Risks, and the State Auditor Is Removing Its High‑Risk Designation

| RISK AREAS AS REPORTED IN APRIL 2021 | STATE AUDITOR’S CURRENT ASSESSMENT OF SAN GABRIEL’S PROGRESS IN ADDRESSING THE RISK AREA* | |

|---|---|---|

| San Gabriel’s Poor Financial Management Has Eroded Its Financial Condition | ||

| 1 | Declining financial health | Partially Addressed |

| 2 | Unfavorable loan agreements | Fully Addressed |

| 3 | Incomplete financial projections | Fully Addressed |

| San Gabriel Needs to Consider Additional Expenditure Reductions and Revenue Increases | ||

| 4 | Rising employee retirement costs | Partially Addressed |

| 5 | Operational losses from the Mission Playhouse | Fully Addressed |

| 6 | Incomplete cost recovery | Fully Addressed |

| Gaps in San Gabriel’s Management Controls Increase the Risk of Inefficiency and Waste | ||

| 7 | Lack of competitive bidding | Fully Addressed |

| 8 | Inadequate contract management | Fully Addressed |

* In accordance with state law, we used our professional judgment to assess the city’s progress in addressing each of the risk areas in the table. We determined whether the steps the city took and the overall conditions relevant to each risk area meant that the city fully or partially addressed the risk areas, or whether substantial action relevant to the risk area was still pending. We explain the statuses identified in this table in more detail below.

Fully addressed: The city has taken sufficient action to address the risk area when we consider its effort in combination with the related conditions at the time of this audit.

Partially addressed: The city has taken sufficient action to address the risk area when we consider its effort in combination with the related conditions at the time of this audit.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #1

Declining Financial Health

Status: We conclude that San Gabriel has partially addressed this risk area by building its general fund reserves and operating at a net surplus in its general fund each year.

In our April 2021 audit, we found that the city’s general fund reserves decreased steadily from fiscal years 2014–15 through 2017–18 because of three primary reasons: a public works loan that restricted the availability of general fund cash due to a collateral requirement, insufficient oversight by the city council, and a lack of transparency by former city management. At the lowest point, the city’s general fund reserves decreased to a deficit of $9.9 million in fiscal year 2017–18.

As a part of this audit, we found San Gabriel’s general fund reserves have recovered largely because of increases in the city’s tax revenue as well as one‑time infusions of funding. At the end of fiscal year 2022–23, the city’s general fund reserves were about $15.8 million—equaling three and a half months of its expenditures for that year. Assisting the city in reaching that level of reserves has been Measure SG, a new sales tax measure that went into effect in July 2020 and that has helped to increase tax revenue to the city from $22 million in fiscal year 2019–20 to $35 million in fiscal year 2022–23. The city also paid off the outstanding balance of its public works loan, which freed more than $5.8 million in funds to be available as unrestricted. Finally, the city used ARPA funds as lost revenue to pay for general government services. The city received a total of $9.5 million in ARPA funds during fiscal years 2020–21 and 2021–22, which allowed it to set aside some of its general fund revenue into reserves.

Although the city has in part relied on one‑time events to rebuild its reserves, it also maintained a cumulative surplus of more than $15 million in its general fund over a three‑year period of fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23. Figure 3 shows the city’s general fund revenue and expenditures for those fiscal years, inclusive of the annual transfers that the city made into the general fund. San Gabriel has historically relied on a special property tax to help pay the retirement costs of city employees (retirement tax), which San Gabriel voters originally approved in 1948. The city maintains the revenue from that tax in its retirement fund. Because this tax supports the city’s ongoing retirement costs, we considered it functionally equivalent to general fund operating revenue.

Figure 3

The City of San Gabriel’s Expenditures Have Been Below Its General Fund Revenue in Three Recent Fiscal Years

Source: San Gabriel’s ACFRs.

Note: We calculated revenue by combining the revenue and other financing sources into the general fund in each fiscal year. We calculated expenditures by combining the expenditures and transfers out of the general fund in each fiscal year.

Figure 3, a bar chart that compares San Gabriel’s general fund revenue to its general fund expenditures for fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23. For fiscal year 2020–21, the bar chart shows that San Gabriel’s general fund revenue was $48.0 million compared to $40.7 million in general fund expenditures. For fiscal year 2021–22, the bar chart shows that San Gabriel’s general fund revenue was $57.2 million compared to $46.8 million in general fund expenditures. For fiscal year 2022–23, the bar chart shows that San Gabriel’s general fund revenue was $53.6 million compared to $53.4 million in general fund expenditures. The bar chart includes a note stating that we calculated revenue by combining the revenue and other financing sources into the general fund in each fiscal year. We calculated expenditures by combining the expenditures and transfers out of the general fund in each fiscal year. The data for this bar chart comes from San Gabriel’s Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports.

San Gabriel has made significant progress in addressing its general fund reserves, but it should continue to build its reserve. The city’s reserve amount as of the end of fiscal year 2022–23 was equivalent to about three and a half months’ worth of that year’s general fund expenditures. Although this amount surpasses the GFOA guidance about minimum reserve levels, the GFOA also advises governments to set their reserve levels at amounts that are appropriate for their unique circumstances. Given that San Gabriel must still address challenges in meeting its OPEB obligations—which we describe more about later—the city would be in a better position if it increased the reserves that it sets aside for potential future financial challenges.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #2

Unfavorable Loan Agreements

Status: We conclude that San Gabriel has fully addressed this risk area by paying the outstanding balance of its public works loan and not entering into additional loan agreements.

As indicated above, the city took out a public works loan of $7.8 million in December 2014, which significantly restricted the city’s ability to fund its city services using cash from the general fund because the loan agreement required that the city pledge an amount of funds equal to the borrowed amount as collateral. Our April 2021 audit report found that the city council and the city’s management team at the time did not adequately evaluate the financial impact of the loan. We recommended that the city develop a plan to renegotiate or refinance the public works loan. In fiscal year 2022–23, San Gabriel paid off the loan’s remaining balance of nearly $6 million, freeing up the general fund money that the bank used as collateral.

San Gabriel has also implemented our recommendation to create a policy that requires city staff to present options and considerations to its city council when entering into debt, including an analysis of alternative methods of financing and the impact on city finances. The city updated its debt management policy per our recommendation in January 2023. Further, other than two lease purchase agreements for the acquisition of public safety equipment totaling $1.4 million, the finance director asserts that the city has not taken on any new loans or debt since we issued our last audit. Before entering into these agreements, city management presented different financing options to the city council and described each option’s potential impact on the city’s finances. For example, in April 2022, city management presented to the city council options for purchasing or leasing two fire apparatuses for the fire department. The city council authorized staff to purchase one apparatus, but only if the terms would be the same as the terms offered for the two apparatuses. Providing these types of analyses allows the city council and city management to make informed decisions and strengthens the city council’s oversight on city finances. San Gabriel has shown improvement in this area, sufficiently addressing the associated risk.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #3

Incomplete Financial Projections

Status: We conclude that San Gabriel has fully addressed this risk area by producing financial projections that provide a reasonable basis for financial planning for major categories of revenue and expenses.

In our April 2021 audit, we found that the city did not consider key factors such as collateral for the public works loan, the impact of the pandemic, nor potential salary increases when developing its five‑year financial projection. We noted that the GFOA considers it a budgeting best practice to analyze major revenue sources to identify forecasting assumptions and determine whether potential trends are likely to continue. To ensure that San Gabriel had relevant information for making decisions, we recommended the city update its financial projections to include in‑depth analysis of key revenue sources and future costs.

To assess the accuracy of San Gabriel’s more recent forecasts, we compared its financial projections for fiscal years 2022–23 and 2023–24 that the city made in its 2021–22 budget to the information about actual financial performance for those years found in the city’s ACFR and budget documents. In general, the city developed conservative projections of its revenue. The largest revenue category for the city is its tax revenue, which was more than 80 percent of the city’s annual revenue in fiscal year 2022–23. For both fiscal years we reviewed, the city’s projection under estimated what its tax revenue would be by more than 10 percent. This underprojection meant that during its budgetary deliberations, the city expected to have less revenue than it would ultimately have at its disposal. We acknowledge that conservative projections of revenue are less problematic than overprojections, which could cause a city to unknowingly plan to spend beyond its capacity.

The city has generally been more accurate when projecting its expenditures. After adjusting for a one‑time debt payment the city made in fiscal year 2022–23, the total expenditures the city made in fiscal years 2022–23 and 2023–24 were both within 10 percent of the forecasted amounts. Personnel costs are close to 75 percent of the city’s general fund expenditures, and the city projected these costs within 5 percent in each of the two fiscal years we reviewed, which is a relatively close margin.

Although San Gabriel’s forecasts have at times been different than its actual financial performance, we found that its projections for fiscal years 2022–23 and 2023–24 were generally close to the city’s actual financial performance and therefore they were reasonable estimations for financial planning purposes. Accordingly, we consider this risk area fully addressed.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #4

Rising Employee Retirement Costs

Status: We conclude that San Gabriel has partially addressed this risk area by contributing to its OPEB trust and reducing post‑employment medical benefits for new employees.

In our April 2021 audit, we estimated that the retirement tax revenue would not be sufficient to cover pension costs from fiscal year 2020–21 through 2024–25. However, in fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23 (the most recently completed ACFR at the time of our audit) the city has covered all but less than 2 percent of its pension costs using the retirement tax revenue it collected in those years, along with the available amounts it has retained as a balance in the associated fund. In other words, the city has not needed to use general fund revenue in any substantive manner to pay for its pension costs.

Although the city may not always be able to pay for its pension obligations through its retirement tax alone, we are not as concerned about the city’s overall ability to pay these pension obligations. The city’s projections show that it will need to use general fund money to cover about $230,000 of its pension obligations in fiscal year 2025–26 and intermittently use general fund money in subsequent fiscal years as well. The city’s finance director explained that the city’s projections assume zero vacant positions to represent the upper threshold of the potential costs it could face. In the event that the retirement tax does not generate enough revenue to cover pension costs, he stated that the city will likely borrow from the general fund and repay the borrowed amount using retirement tax revenues generated in the following years. The city’s projections show that in each year where the city expects to borrow from the general fund to pay for pension obligations, the retirement tax will generate enough revenue in the subsequent years to repay the general fund within two years.

In addition, our April 2021 audit report found that the city had been paying less than the amount needed to fully fund the costs of its OPEB benefits, increasing its total net obligation for OPEB. We noted that the city’s unfunded OPEB liability nearly doubled in only two years, in part because the city had stopped prefunding these costs. As of the June 2023 reporting date, the city’s net OPEB funding ratio was 13 percent, with more than $44 million in unfunded liability.

San Gabriel has taken some steps to address its OPEB liability. At the time of our April 2021 audit, San Gabriel did not require its employees to contribute to their OPEB costs, and we recommended that the city negotiate with its unions to require employees to contribute. According to the finance director, the city’s primary focus has been on removing the lifetime medical benefit for future employees rather than negotiating with employees to contribute to the OPEB liability. The city negotiated with its unions to change post‑employment medical benefits for employees hired after January 2023 to the Public Employees’ Medical Hospital Care Act (PEMHCA) statutory minimum level of benefits. In order to calculate the savings resulting from eliminating the lifetime medical benefit and assigning new employees to the PEMHCA plan, the finance director stated that the city would need to contract the services of an actuarial firm. Although the magnitude of the benefit the city will eventually realize from this change is not clear, the step the city has taken will have positive effects on its overall retirement obligations at some time in the future.

In addition, the city contributed to its OPEB trust for the first time in five years. The city’s OPEB trust provides a way for the city to prefund its OPEB obligation and reduce its overall OPEB liability. In June 2024, the city contributed $250,000 to the OPEB trust, bringing the trust’s cumulative value to nearly $8.3 million. Also, the city has budgeted another $250,000 payment towards the trust in fiscal year 2024–25 and included contributions in this amount each year in its five‑year forecast through fiscal year 2029–30. Although these are positive steps towards addressing the city’s OPEB liabilities, the annual contribution amount is very small compared to the city’s overall liability for OPEB. Even an annual contribution of double the amount the city is planning on making would increase the city’s OPEB funding ratio by only 1 percent when using the outstanding liability of $44 million we describe above. Therefore, based on the actions it has taken and the sizeable OPEB liability the city still incurs, we consider the city to have partially addressed this risk area.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #5

Operational Losses From the Mission Playhouse

Status: We conclude that San Gabriel has fully addressed this risk area by reducing the general fund subsidies it provides.

Our April 2021 audit report noted concerns regarding the Mission Playhouse’s significant and consistent operating deficits that required the city to provide funding for it to remain solvent. The city subsidizes the operations of its Mission Playhouse—a community center that hosts various events, such as theater and music performances, and public meetings. According to the city’s ACFRs, for fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23, the playhouse continued to operate at a deficit and relied on general fund transfers. The finance director confirmed that the city council is committed to providing the Mission Playhouse services to the public and that it views the theater as a vital arts and entertainment service for the community. The finance director highlighted that the city has more recently decreased the amounts it transfers from its general fund. In fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23, the city transferred slightly more than $1 million to the Mission Playhouse—an average of $350,000 each year. This average represents a significant reduction in transfers, namely half the amount we reported in our April 2021 audit, thus indicating that the city has made efforts to reduce its costs.

In addition, the city has made efforts to improve costs and operations at the Mission Playhouse. For example, the city eliminated the Mission Playhouse director position from its fiscal year 2021–22 budget and assigned oversight of the playhouse to the community services director. The playhouse’s budgeted expenses decreased 22 percent that fiscal year. Further, the playhouse obtained a new ticketing system that the city asserts better serves its needs, results in lower ticket fees, and offers a more user‑friendly interface for staff compared to its previous system.

In light of the significant decrease in the amount of the general fund subsidy, the efficiency gains, and the public benefit that the Mission Playhouse provides, we consider the city to have fully addressed this risk area.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #6

Incomplete Cost Recovery

Status: We conclude that San Gabriel has fully addressed this risk area by updating its service fees annually.

In our April 2021 audit, we noted that the city had not evaluated whether the fees it charged for services aligned with the full cost of those services. In addition, we identified that the city had not adjusted a majority of its fees since 2016, and some had not changed since 2002. Consequently, the city had not ensured that it collected the commensurate amount of revenue that could have helped relieve the financial burden on the city’s general fund. To ensure that the fees it charged for services align with their costs, we recommended that San Gabriel implement policies and procedures requiring it to reevaluate the cost of its fee‑funded services at least every three years.

The city has increased its service fees and plans to increase those fees annually as adjusted to the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for the Los Angeles Metro area. The city’s March 2021 fee study determined that the city’s fiscal year 2020–21 fee revenue recovered only 42.5 percent of the city’s service costs, causing the city to lose nearly $6.6 million in subsidies. In the two fiscal years following the study, San Gabriel’s revenue from its charges for services averaged $4 million—an increase of 64 percent compared to the revenue the city generated in fiscal year 2020–21. In addition, from fiscal years 2021–22 through 2024–25, the city council passed annual resolutions that require the city to conduct comprehensive fee reviews at least once every five years to ensure that it is adequately recovering the cost of providing services. The finance director stated that the city intends to complete another fee study in fiscal year 2025–26. Because it has raised its fees to collect revenue more commensurate with its costs and plans to take similar action in the future, we consider this risk area addressed.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #7

Lack of Competitive Bidding

Status: We conclude that San Gabriel has fully addressed this risk area by updating its contract bidding policy, and we no longer have concerns about its waste collection agreement.

In our April 2021 audit, we recommended that San Gabriel strengthen its purchasing policies to competitively bid services at least every three years or to document a justification for services that require a longer contract duration. In June 2023, the city updated its contract management administrative procedures, which are intended to strengthen the city’s purchasing policies and help to ensure that the city is receiving the best value on all contracted goods and services. The updated procedures direct city staff to rebid contracts for most services every three to five years, a variation from the three‑year interval we recommended. The finance director explained that with the exception of its waste collection contract, the city’s contracts have durations of three years and allow for two one‑year extensions. The finance director further explained that the city’s reasoning for allowing contracts with terms as long as five years before being rebid, is that the process to procure services takes a significant amount of administrative time and effort—sometimes taking up to a year to complete—and that the market for services does not change significantly in a period of three years. Because San Gabriel’s updated procedures direct staff to present service contracts to the city council at least every five years and to rebid contracts at this same frequency, we conclude that the city has ensured that it will regularly use the competitive bidding process.1

In addition, we conclude that the city’s waste collection contract no longer presents an immediate risk to the city. In our prior report, we noted concern that San Gabriel had not verified whether its waste collection contract provided the best value to its residents and recommended the city renegotiate with its waste collection company to revise the terms of the agreement. However, in 2023 the city conducted a survey of the residential waste hauler rates of four nearby cities, which showed that San Gabriel’s rates were the median rates among all of the cities. Further, according to the contract agreement with the waste collection vendor, any increases to waste collection rates that exceed the increase in the CPI would require the approval of the city council, which means that the city has a control in place to manage the rates its residents pay.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #8

Inadequate Contract Management

Status: We conclude that San Gabriel has fully addressed this risk area by developing a centralized system to track current contracts and implementing purchase order controls.

Our April 2021 audit found that San Gabriel did not have a centralized system for monitoring its contracts, which compromised its ability to prevent departments from overspending the amount of their contractual service budgets. We further noted that, because of its insufficient contract tracking system, the city could not track the total costs associated with each of its contracts over multiple years, and city management could not determine total citywide annual contract costs. In June 2023, the city implemented contract management administrative procedures that established a centralized contract depository and strengthened the city’s purchasing controls. The procedures require departments to submit contracts approved by the city council to the city clerk, who is supposed to maintain and regularly update a centralized spreadsheet to track the contract vendor, responsible department, and the contract expiration date. We obtained a copy of this spreadsheet and verified that recently approved contracts were included on the spreadsheet. In addition, the city’s contract management procedures include purchase order controls that require the finance department to verify that the contract is valid, properly authorized, and that funds are available in the current budget before payments under contracts are allowed. Because of the improvements described above, we conclude that the city has addressed this risk area.

The City of Blythe Has Addressed Challenges Related to Its Long‑Term Financial Stability, and the State Auditor Is Removing Its High‑Risk Designation

| RISK AREAS AS REPORTED IN MARCH 2021 | STATE AUDITOR’S CURRENT ASSESSMENT OF BLYTHE’S PROGRESS IN ADDRESSING THE RISK AREA* | |

|---|---|---|

| Blythe’s Financial Stability Remains Uncertain Even With Recent Improvements | ||

| 1 | Low financial reserves | Fully Addressed |

| 2 | Need for additional sources of revenue | Fully Addressed |

| 3 | Lack of a long-term plan | Pending |

| Blythe Must Address Deficits in Its Enterprise Funds as Well as Unmet Safety and Infrastructure Needs | ||

| 4 | Enterprise fund deficits | Partially Addressed |

| 5 | Unpaid golf course loan | Fully Addressed |

| 6 | Need for public safety resources | Fully Addressed |

| 7 | Unaddressed vacant buildings | Fully Addressed |

| The City Needs More Effective Management Practices to Improve Its Financial Stability and Its Ability to Provide Services to Residents | ||

| 8 | Utility rates and service fees insufficient to cover costs | Fully Addressed |

| 9 | Poor oversight of city contracts | Partially Addressed |

| 10 | Lack of a permanent city manager | Pending |

* In accordance with state law, we used our professional judgment to assess the city’s progress in each of the risk areas in the table. We determined whether the steps the city took and the overall conditions relevant to each risk area meant that the city fully or partially addressed the risk areas, or whether substantial action relevant to the risk area was still pending. We explain the statuses identified in this table in more detail below.

Fully addressed: The city has taken sufficient action to address the risk area when we consider its effort in combination with the related conditions at the time of this audit.

Partially addressed: The city has taken positive action to address the risk area, but its effort is incomplete when we consider it in combination with the related conditions at the time of this audit.

Pending: The city has not taken substantial action to address the risk area and, at the time of this audit, the conditions that created high risk for the city continue to exist.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #1

Low Financial Reserves

Status: We conclude that Blythe’s increased general fund reserve demonstrates that it has fully addressed this risk area.

In our March 2021 audit, we determined that Blythe’s general fund reserve at the end of fiscal year 2019–20 was $804,000, which was only a little more than one month’s worth of operating funds. At the end of fiscal year 2022–23, Blythe had a general fund reserve of $8.3 million, an increase of more than $7 million. This amount was equivalent to more than seven months of annual expenditures, which exceeded both the three months of expenditures that the city’s reserve policy states the city will maintain and the GFOA best practice of at least two months.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #2

Need for Additional Sources of Revenue

Status: We reported in March 2022 that Blythe had fully addressed this risk area. After that determination, the State decided to close Chuckawalla Valley State Prison. The economic impact of the closure will likely mean that Blythe would benefit from finding additional revenue, but the city has taken steps to address that need.

In 2022 Blythe contracted with a vendor to research economic development opportunities in the city and recruit retail businesses. In addition, in March 2022, we reported the city’s assertion that it had engaged with stakeholders in a formal economic development effort. These actions led us to conclude that the city had fully addressed this risk area. Subsequent to that conclusion, in December 2022, the State announced its plan to close the Chuckawalla Valley State Prison, which is located in Blythe. Originally planned to close in March 2025, the prison officially closed in November 2024.

The city commissioned a June 2023 study of the economic and fiscal impact of the prison closure, which estimates that the full effect of the closure on the city’s general fund revenue will be a reduction of $1.9 million, or about 12 percent, annually. The study also found that the prison supported 13 percent of the total jobs held by Blythe residents and 22 percent of the city’s total wages. The study determined that the prison closure will raise the unemployment rate, considerably reduce average household incomes, and put pressure on local business, which will experience losses of both sales and profits. Figure 4 shows that the city’s general fund revenue exceeded expenditures during fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23, indicating that the city can absorb some loss in revenue. Nonetheless, the actual effect of the prison closure remains unknown, and the city will need to be careful to avoid relying on other funding to sustain operations at their present levels.

Figure 4

The City of Blythe’s General Fund Revenue Has Consistently Exceeded Its Expenditures

Source: Blythe’s ACFRs.

Note: We calculated revenue by combining the revenue and transfers into the general fund in each fiscal year. We calculated expenditures by combining the expenditures and transfers out of the general fund in each fiscal year. The city did not have other financing sources or uses flowing in or out of its general fund in these three fiscal years.

Figure 4, a bar chart that compares Blythe’s general fund revenue to its general fund expenditures for fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23. For fiscal year 2020–21, the bar chart shows that Blythe’s general fund revenue was $12.7 million compared to $10.9 million in general fund expenditures. For fiscal year 2021–22, the bar chart shows that Blythe’s general fund revenue was $16.2 million compared to $13.0 million in general fund expenditures. For fiscal year 2022–23, the bar chart shows that Blythe’s general fund revenue was $16.4 million compared to $13.8 million in general fund expenditures. The bar chart includes a note stating that we calculated revenue by combining the revenue and transfers into the general fund in each fiscal year. We calculated expenditures by combining the expenditures and transfers out of the general fund in each fiscal year. The city did not have other financing sources or uses flowing in or out of its general fund in these three fiscal years. The data for this bar chart comes from Blythe’s Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports.

A recent study by a consultant hired by Riverside County, where Blythe is located, could provide the city with a roadmap for economic development and thereby a path towards financial sustainability in the wake of the prison closure. In early 2024, this consultant presented an overview of the results of an economic development study of the Blythe region. The study included several action steps that could stimulate economic growth in the area, such as making infrastructure investments and encouraging and attracting private investment in the area. For example, the study suggested attracting tourism and capitalizing on Blythe’s location along a regional highway system, the I‑10 corridor, by investing in charging infrastructure for electric vehicles. The study also recommended pursuing grant opportunities to help fund this type of infrastructure, and Blythe has already sought such grants. The city received a federal grant award of $19.6 million for the development of a publicly accessible, multi‑class, electric vehicle charging facility. The interim city manager believes that renewable energy, along with tourism and distribution centers will be key in Blythe’s recovery from the prison closure. According to the interim city manager, Riverside County will organize a work group of stakeholders at the start of 2025 to implement the economic development study’s action items. She stated that the city hopes to have these investments made in the community over the next three to five years, assuming that funding is available.

Finally, the city will also benefit from the remaining ARPA funding it has yet to spend. The city received a cumulative total of $4.7 million in ARPA funding and, according to the city’s reporting to the federal government, the city had about $3 million of that funding still left to spend on general government activities as of the end of March 2024. The funding will be available to the city until December 2026, when federal regulations require the city to return any obligated but unspent funds.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #3

Lack of a Long‑Term Plan

Status: We conclude that Blythe has not addressed this risk area because the city has not yet developed a long‑term strategic plan.

In our March 2021 audit, we recommended that the city develop a five‑year strategic plan to ensure that Blythe was adequately prepared to address long‑term financial, budgetary, and operational challenges. As part of that audit, we observed that a strategic plan would provide a framework for Blythe city officials to consider the city’s numerous competing priorities when allocating any additional revenue it received. Consequently, we reviewed whether the city had addressed this recommendation. The interim city manager explained that the city has not done so because it has devoted resources to other priorities, such as opposing the Chuckawalla Valley State Prison closure. Moving forward, she stated that city staff will ask the city council to approve funding for a strategic plan as part of Blythe’s fiscal year 2025–26 budget. The interim city manager estimated adoption of a strategic plan by early 2026 if the city council approves the funding.

HIGH‑RISK AREA #4

Enterprise Fund Deficits

Status: We conclude that Blythe has partially addressed this risk area because the city’s enterprise funds no longer owe significant amounts to other city funds. Although the city’s enterprise funds continue to have negative unrestricted net positions, the city’s recent rate increases reduce the risk that the water fund will strain the city’s general fund.

In our March 2021 audit, we reported that Blythe had subsidized its solid waste, golf course, and lighting district enterprise funds with other city funds. We reported that the city recorded these enterprise fund subsidies as loans that cumulatively amounted to more than $1.5 million. During this audit, we reviewed the city’s fiscal year 2022–23 ACFR and found that the city’s enterprise funds subsequently owe minimal amounts to other city funds, which resolves the condition that we found in our original audit. Specifically, the golf course and lighting district funds did not owe any amounts to other funds, and the solid waste enterprise fund owed only $101,000 to the general fund.