2024-047 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

The University of California Lacks the Accountability and Urgency Necessary to Promptly Return Native American Remains and Cultural Items

Published: April 15, 2025Report Number: 2024-047

April 15, 2025

2024-047

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, CA 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As required by Health and Safety Code section 8028, my office conducted its third audit of the University of California’s (university) compliance with the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA) and its 2001 California counterpart, CalNAGPRA. These acts establish requirements for the repatriation of Native American human remains (remains) and cultural items to tribes by government agencies and museums—which include the university’s campuses—that maintain collections of remains and cultural items. This report concludes that the university lacks the accountability and urgency needed to promptly return Native American remains and cultural items.

Despite years of external attention on the university’s NAGPRA efforts, the university Office of the President’s oversight of campuses has been deficient. Although campuses have continued to discover collections of remains and cultural items since our last audit, the campuses have not yet completed their searches for undiscovered collections, and the Office of the President has not systematically kept track of campuses’ search efforts. The Office of the President has also not established explicit standards for the care of all campus collections. In that absence, one campus has several outstanding loans of potential cultural items and at another campus, some potential cultural items were stolen in 2022. Of additional concern, the Office of the President has not created an oversight environment that ensures accountability for compliance with NAGPRA. For example, the Office of the President did not ensure campuses developed full repatriation timelines. Because the Office of the President did not establish systemwide repatriation goals, campuses have contributed funding to NAGPRA without a clear understanding of whether these amounts were appropriate. We believe that the Legislature should consider directly appropriating funding for NAGPRA activities so that it can direct the university’s NAGPRA activities more closely.

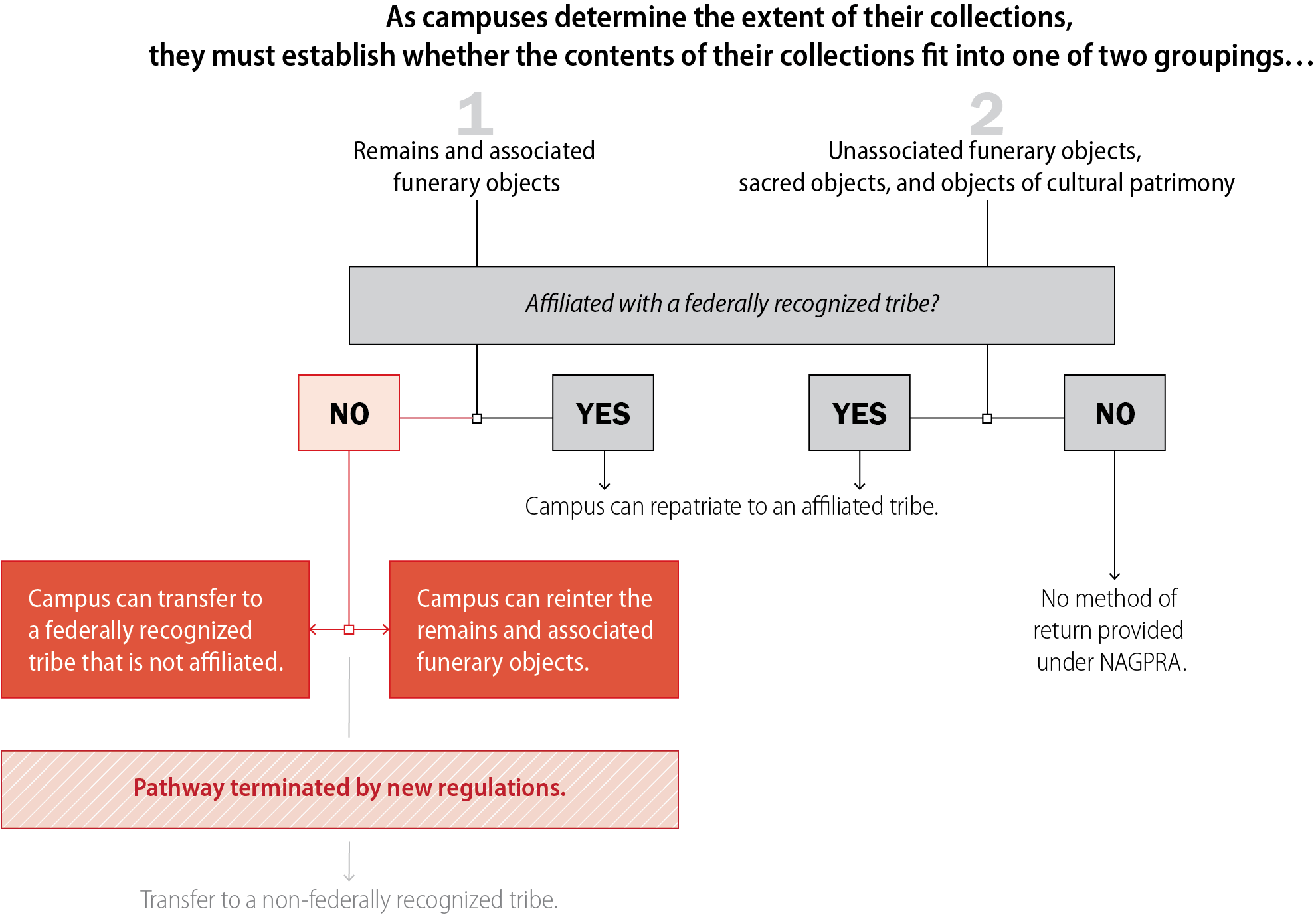

Finally, recent changes to the federal regulations governing NAGPRA present challenges to California’s repatriation goals. Specifically, NAGPRA’s revised regulations no longer allow campuses to transfer certain remains and cultural items to California tribes lacking federal recognition, which has hampered the campuses’ ability to meet one of CalNAGPRA’s goals. In response, the university should initiate discussions with tribes to determine their preferences for reinterment of the remains and cultural items and then abide by those preferences.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| CalNAGPRA | California Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act |

| NAGPRA | Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act |

| NAHC | Native American Heritage Commission |

Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations

The federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), passed in 1990, and its 2001 California counterpart (CalNAGPRA) establish requirements for the return of Native American human remains (remains) and cultural items. Government agencies and museums, including universities, must repatriate, or return, these remains and cultural items to tribes affiliated with them. This audit is the third that our office has conducted of the University of California’s (university) compliance with NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA. To complete this audit, we reviewed four campuses—Berkeley, Riverside, San Diego, and Santa Barbara—as well as the Office of the President and conclude the following:

The University Does Not Know How Much Work Remains to Achieve Full Repatriation and Has Not Properly Cared for All Items It Possesses

Although we found that campuses have continued to repatriate remains and cultural items, it has been more than 30 years since the establishment of NAGPRA, and the university’s campuses still hold the remains of thousands of individuals, as well as hundreds of thousands of cultural items and potential cultural items. We refer to these remains, cultural items, and potential cultural items as collections. A variety of factors, including some that are outside of the university’s control, create uncertainty about when the campuses will complete repatriation of their collections. However, at their current pace, we estimate that it may take some campuses over a decade to reach full repatriation.

Further, additional collections continue to be revealed. In one case, we found that Santa Barbara had not reported all of its collections to the national NAGPRA program and its state equivalent and, because of that, it is likely that tribes have an incomplete understanding of that campus’s holdings. The campuses also continue to discover previously unknown collections. For example, both Riverside and San Diego recently discovered previously unknown remains on their campuses, and Santa Barbara identified approximately 1,500 potential cultural items about which it was previously unaware. Although the university’s systemwide NAGPRA policy (systemwide policy) requires campus NAGPRA staff to periodically search campus departments at high risk of having undiscovered NAGPRA collections, campuses’ searches are not complete, and the Office of the President has not systematically kept track of the searches campuses have performed.

Finally, we found instances in which the university has not properly cared for all items in its possession. For example, Santa Barbara has not yet retrieved several outstanding loans of potential cultural items, and Davis displayed potential cultural items in a campus lecture hall from which they were stolen in 2022. The systemwide policy does not explicitly state how campuses should handle or store potential cultural items.

Despite Years of External Attention, the Office of the President’s Oversight of Campuses’ NAGPRA Implementation Is Deficient

The Office of the President has not effectively overseen the university’s compliance with NAGPRA, despite years of increased external attention. We found that the Office of the President has not created a framework of policies and practices that ensures accountability for compliance or effective and efficient repatriation. For example, the Office of the President required campuses to plan for how they would repatriate their collections, but it did not hold campuses accountable when the plans lacked required timelines or when campus plans became outdated. The university’s systemwide NAGPRA committee (systemwide committee) noted deficiencies when reviewing the plans, but the Office of the President did not require campuses to make corrections, thereby limiting the usefulness of these plans for the systemwide committee’s efforts to oversee campus repatriation. Also, since 2022 when it established its expectation that campuses plan for repatriation, the Office of the President has not established systemwide performance goals for repatriation. Although campuses established certain campus-specific goals, the Office of the President did not hold campuses accountable for their actual performance. For example, the Office of the President has not monitored whether campuses have met their goals to repatriate specific collections within the last few years.

Because the university lacks systemwide performance goals, it has contributed funding toward NAGPRA compliance without a clear understanding of whether these amounts were appropriate. The Office of the President’s review of campuses’ NAGPRA budgets noted whether these budgets balanced personnel and non‑personnel costs, but it did not determine whether the budgeted amounts were appropriate for meeting specific goals or benchmarks at each campus. Each campus’s budget represents the total amount of resources the campus plans to spend on its NAGPRA activities. However, we found that three campuses—Berkeley, San Diego, and Santa Barbara—carried over to future fiscal years significant amounts of unspent funding they had allocated to NAGPRA, including funding meant to support tribes. Given the pervasive weaknesses we observed in the Office of the President’s oversight of NAGPRA, we believe the Legislature may have a role in applying external accountability—such as by earmarking a specified amount of the university’s appropriation identified for NAGPRA—to improve the university’s performance.

Recent Changes to Federal Regulations Present Challenges to California’s Repatriation Goals

Effective January 2024, the federal regulations that govern the implementation of NAGPRA changed. Some of these changes have significant impacts for CalNAGPRA, which used to provide an avenue for the transfer of certain remains and cultural items to non-federally recognized California tribes. The revisions to the federal regulations no longer allow campuses to transfer certain remains and certain items to non‑federally recognized tribes, severely hampering campuses’ ability to fulfill the intent of CalNAGPRA. We identified no clear path for the State to amend CalNAGPRA to allow for campuses to transfer certain remains and items to non‑federally recognized tribes in conformity with NAGPRA. However, the university can initiate discussions with tribal stakeholders regarding any preferences they may have for reinterment protocols and adopt these protocols as part of any revised systemwide policy.

To address our findings, we have made recommendations to the university to create a strong system for identifying undiscovered remains and items and strengthen its requirements regarding the proper care of potential cultural items. We recommend that Santa Barbara report all of its collections as required. We further recommend that the Office of the President require campuses to create and update timelines for completing specific activities, establish systemwide performance goals, monitor the university’s progress in meeting its goals, and ensure that campus budgets align with those goals. In addition, we recommend that the university engage tribes to study their costs related to repatriation and align its systemwide policy with the revised federal regulations.

Agency Comments

The Office of the President and Santa Barbara agreed with our recommendations and stated they would implement them.

Introduction

Background

The U.S. Congress passed NAGPRA in 1990 to create a process by which Native American tribes with ancestral, cultural, or geographic links to remains and cultural items can request their return from government agencies and museums, a process known as repatriation.1 The text box shows the definitions that NAGPRA’s implementing regulations create for the different types of cultural items that NAGPRA governs. The U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI), which administers NAGPRA, has established those regulations. In 2023, DOI significantly revised NAGPRA’s implementing regulations, and these revisions became effective in January 2024.

Types of Cultural Items Subject to NAGPRA

- Funerary Object: Any object reasonably believed to have been placed intentionally with or near remains. Funerary objects include any object connected to a death rite or ceremony of a Native American culture.

- Associated Funerary Object: Any funerary object related to remains that were removed and the location of the remains is known.

- Unassociated Funerary Object: Any funerary object that is not an associated funerary object, and may be identified as, among other things, related to remains but the remains were not removed, or the location of the remains is unknown.

- Object of Cultural Patrimony: An object that has ongoing historical, traditional, or cultural importance central to a Native American group.

- Sacred Object: A specific ceremonial object needed by a traditional religious leader for present-day adherents to practice traditional Native American religion.

Source: Federal law.

The university and its campuses are required to comply with NAGPRA, and several of the university’s campuses have collections of remains and cultural items that tribes may claim under NAGPRA. NAGPRA’s implementing regulations define the various relationships campuses have with these remains and cultural items. In the case of possession or control, a campus’s responsibility can extend to a responsibility to repatriate remains and cultural items to a tribe. To simplify our terminology, we use the term possession in this report to refer to both possession and control.

The distinction between two groups of Native American tribes is important for understanding NAGPRA’s application. The federal government recognizes certain Native American tribes as eligible for the special programs and services it provides, tribes that we refer to as federally recognized tribes. Alternatively, the federal government does not recognize other Native American tribes in the same way. We refer to those tribes as non-federally recognized tribes. Only federally recognized tribes can receive repatriated remains and cultural items under NAGPRA. The federal government does not recognize many tribes from California because it cancelled its recognition of them beginning in the 1950s, although some tribes have since regained their recognition. Accordingly, approximately 60 tribes from California cannot receive repatriated remains and cultural items through NAGPRA. We refer to non-federally recognized tribes from California as California tribes.

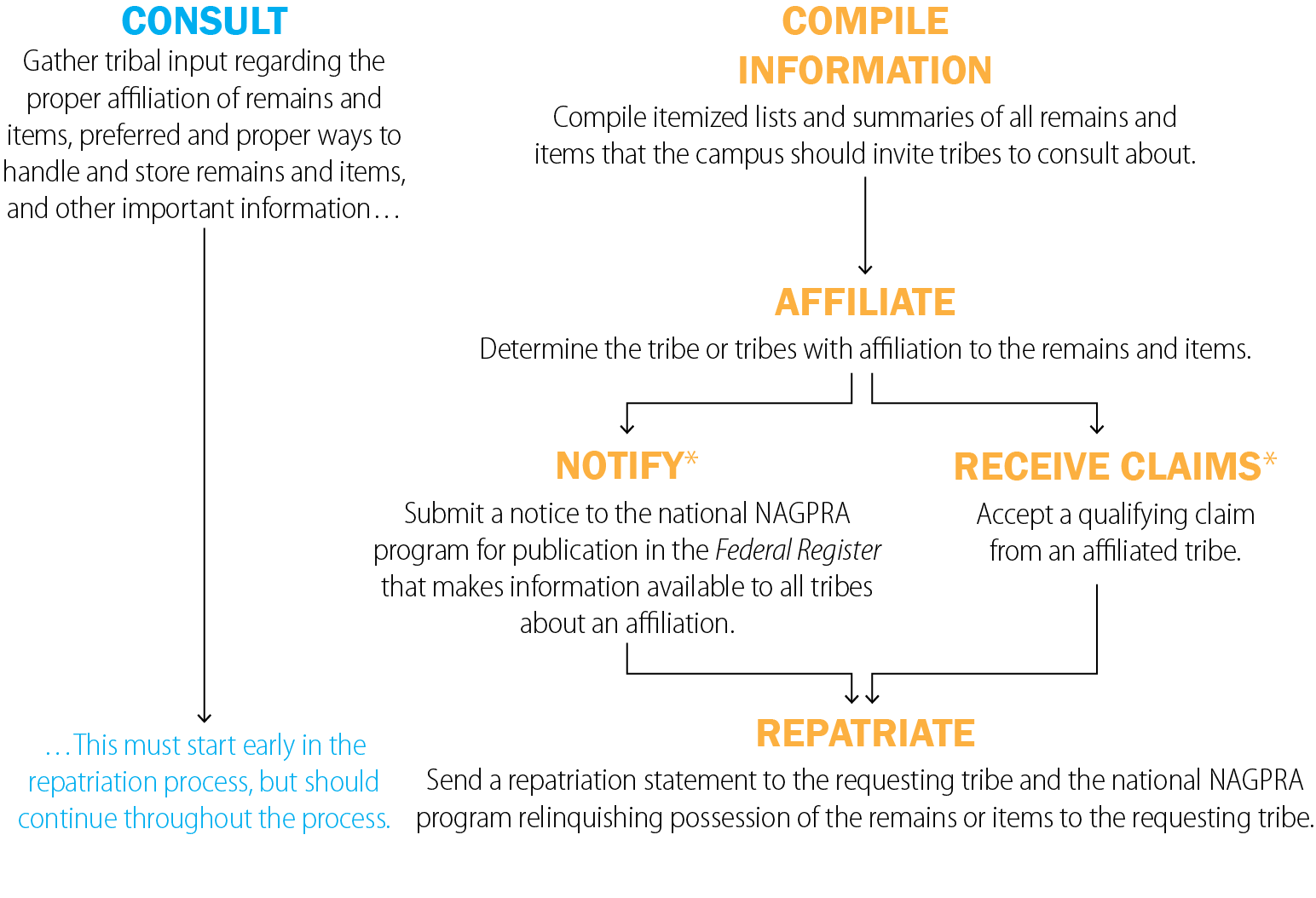

NAGPRA Establishes Steps Campuses Must Take in Consulting With Tribes to Affiliate and Repatriate Remains and Cultural Items

NAGPRA requires campuses to determine whether they possess remains or cultural items that federally recognized tribes may claim through NAGPRA. Figure 1 outlines the steps campuses generally must take when reviewing what they possess, notifying tribes about any remains or potential cultural items in their possession, and following NAGPRA’s requirements to repatriate under specified circumstances. The first step campuses must complete is compiling information about the remains and cultural items they possess in the form of an itemized list of a campus’s known remains and associated funerary objects, and a summary of any holding or collection that may contain unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, or objects of cultural patrimony. After compiling this information, campuses must initiate consultation with any federally recognized tribe that may be affiliated with the remains or potential cultural items in the campuses’ possession. Afterward, campuses must submit a completed list of remains and associated funerary objects to the national NAGPRA program within the DOI in the form of an inventory. Campuses must have submitted the summary of other items before consultation. NAGPRA initially required campuses to complete their summaries and inventories by 1993 and 1995, respectively, and the January 2024 changes to NAGPRA’s implementing regulations imposed additional deadlines to complete summaries and inventories if, for example, campuses located previously unknown, or acquired possession of, new remains or cultural items. In addition, the January 2024 changes created a requirement for campuses, under certain circumstances, to update specified inventories by January 2029.2

Figure 1

The Repatriation Process Requires Campuses to Complete Several Steps

Source: NAGPRA and its implementing regulations.

* Depending on whether a campus is attempting to repatriate items from an itemized list or a summary, NAGPRA’s implementing regulations affect which of these steps occurs first. For unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony, an affiliated tribe must first submit a qualifying claim to a campus, after which the campus sends a notice for publication in the Federal Register. For remains and associated funerary objects, the campus must first send a notice for publication and then tribes may submit claims.

The figure is structured as two timelines appearing next to each other. The first timeline on the left has a single step that occurs throughout the entire repatriation process. On the right, there is a second timeline with five steps. The first step appears at the top of the page with subsequent steps appearing below.

The timeline on the left displays the consultation requirement of the repatriation process. It states “Consult: Gather tribal input regarding the proper affiliation of remains and items, preferred and proper ways to handle and store remains and items, and other important information…” An arrow runs down from this description to encompass the rest of the figure and show that consultation must continue occurring during all other repatriation steps. The downward arrow ends at another text block which explains that consultation “must start early in the repatriation process, but should continue throughout the process.”The timeline on the right describes the five steps campuses must complete while consulting with tribes. The first step campuses must do is compile itemized lists and summaries of all remains and items that the campus should invite tribes to consult about.

The next step is for campuses to determine the tribe or tribes with affiliation to the remains and items.

The next two steps are that campuses must either 1) submit a notice to the national NAGPRA program for publication in the federal register that makes information available to all tribes about an affiliation, or 2) accept a claim from a qualifying tribe. The order of these steps are dependent on whether a campus is attempting to repatriate items from an itemized list or a summary, NAGPRA’s implementing regulations affect which of these steps occurs first. For unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony, an affiliated tribe must first submit a qualifying claim to a campus, after which the campus sends a notice for publication in the Federal Register. For remains and associated funerary objects, the campus must first send a notice for publication and then tribes may submit claims.

The last step is for a campus to complete a repatriation is to send a statement to the requesting tribe and the national NAGPRA program relinquishing possession of the remains or items to the requesting tribe.

Campuses consult with tribes to determine, among other things, whether one or more tribes is affiliated with the remains and cultural items being consulted on and to allow tribes to identify which of NAGPRA’s categories of cultural items applies. Under NAGPRA, cultural affiliation means there is a reasonable connection between a tribe and remains or cultural items based on relationship of shared group identity. Establishing affiliation is critical as, generally speaking, only affiliated tribes are qualified to submit a request for repatriation. Consultation must also address whether the cultural items in a campus’s possession are funerary objects, sacred objects, or objects of cultural patrimony. As such, campuses will not have identified whether items in their collections are cultural items as defined by NAGPRA until they have consulted with all potentially affiliated tribes. As the text box indicates, we use the term remains and cultural items throughout this report to refer to those that have been identified through consultation as being subject to NAGPRA. Similarly, we use the term potential cultural items to refer to items about which campuses must still consult with tribes and that may or may not eventually be identified as being subject to claims under NAGPRA.

NAGPRA Terminology Used Throughout the Report

Remains: Physical remains, including bones, of people of Native American ancestry.

Cultural item: A funerary object, sacred object, or object of cultural patrimony according to the Native American traditional knowledge of a tribe.

Potential cultural item: An item that may be a cultural item, but has not yet been identified as a cultural item, for example, through consultation.

Collection: An accumulation of one or more cultural items, potential cultural items, or remains for any purpose.

Source: Federal law.

Once a campus affiliates remains and cultural items, an affiliated tribe or tribes may obtain these remains and cultural items by submitting a repatriation claim. NAGPRA’s implementing regulations require campuses to submit specified notices about the affiliated remains and cultural items to the national NAGPRA program to be published in the Federal Register.3 Specifically, campuses must submit a notice of inventory completion after completing or updating an inventory, and submit a notice of intended repatriation after completing a summary and receiving a qualifying request for repatriation. Campuses must respond to requests and repatriate remains and cultural items to qualified claimants according to the timelines set forth in NAGPRA’s regulations.

CalNAGPRA Creates Additional Requirements That Apply to Non-Federally Recognized Tribes in California

Enacted in 2001 and revised significantly effective in 2021, CalNAGPRA is intended to provide a mechanism for California tribes to submit repatriation claims to California agencies and museums for remains and cultural items. Many of NAGPRA’s steps summarized above—including the requirement to consult with tribes and to affiliate remains and cultural items to specific tribes—are present in CalNAGPRA as well. However, unlike NAGPRA, which applies to federal agencies and museums as defined under NAGPRA, CalNAGPRA applies to California agencies and museums as defined under CalNAGPRA.4 Accordingly, the university’s campuses are also required to comply with CalNAGPRA.

Unlike NAGPRA, which deals primarily with federally recognized tribes, CalNAGPRA allows California tribes to participate in the repatriation process. In addition, CalNAGPRA requires that campuses submit information about remains and potential cultural items to the State’s Native American Heritage Commission (NAHC). This requirement is similar to the requirement in NAGPRA for campuses to submit inventories and summaries to the national NAGPRA program. However, unlike NAGPRA, CalNAGPRA also requires the campuses to consult with both federally recognized and non-federally recognized tribes from California when completing this work. In effect, this means campuses must include non-federally recognized tribes when determining the affiliation of the remains or cultural items that are in the campuses’ possession.

CalNAGPRA requires campuses to adhere to both CalNAGPRA and NAGPRA when repatriating remains and cultural items to tribes. Specifically, campuses must meet the requirements of all of NAGPRA’s implementing regulations—including those governing the completion of inventories and summaries, consultation, and publication in the Federal Register—to repatriate remains and cultural items under CalNAGPRA. Before January 2024, NAGPRA’s implementing regulations explicitly permitted remains and associated funerary objects that could not be affiliated with a federally recognized tribe through the inventory process to be transferred directly to a non‑federally recognized tribe provided that other conditions were met. However, beginning in January 2024, NAGPRA’s regulations no longer permit this option. Removal of this option from NAGPRA now prevents campuses from returning these remains and associated funerary objects directly to California tribes under CalNAGPRA, including to tribes affiliated with those remains and cultural items. We describe the impact of this change in more detail later in the report.

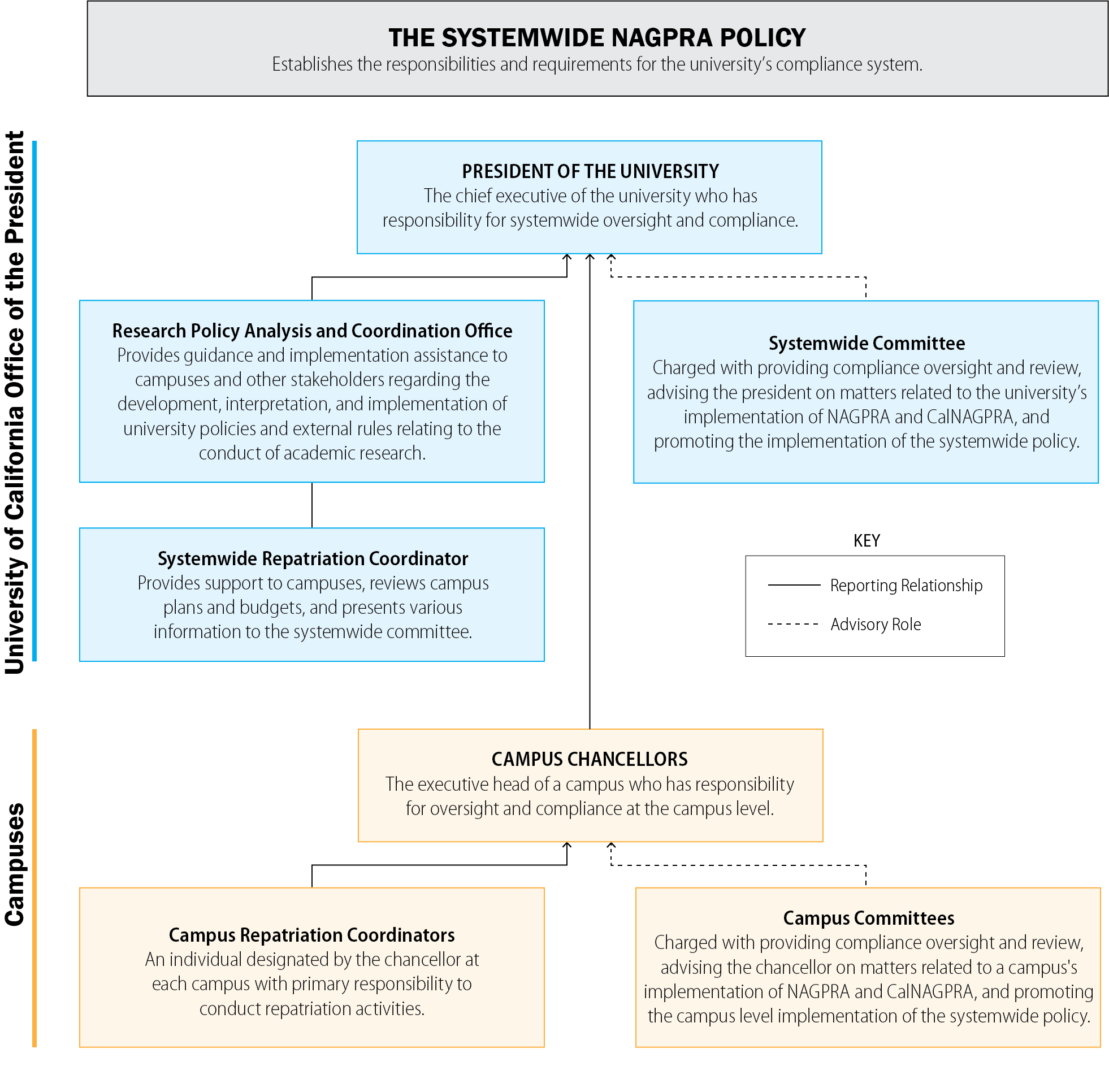

The University Has Established a Policy for Complying With NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA

The university has established several administrative requirements to comply with NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA’s requirements. For instance, the university updated its systemwide policy in 2022 to respond to changes in CalNAGPRA. The university has also established both a systemwide NAGPRA committee (systemwide committee), as well as NAGPRA committees at those campuses with NAGPRA collections. According to state law, the systemwide committee’s role is to review and advise the university on matters related to the university’s implementation of legal requirements to increase repatriation of remains and cultural items. The systemwide policy further defines this advisory role, indicating that the systemwide committee may make recommendations to the university’s president and provide compliance oversight. However, the policy does not grant the systemwide committee the power to require campuses to comply with its recommendations. Finally, the university has instructed all campuses holding more than 100 remains or cultural items to employ full-time repatriation coordinators, to whom the systemwide policy assigns significant responsibility for repatriation activities. Figure 2 shows an overview of the university’s operational structure for addressing NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA.

Figure 2

The University’s Repatriation Functions Are Distributed Among Several Responsible Parties

Source: Systemwide policy and the Office of the President’s website and organizational charts.

This figure is an organizational flowchart that lists different university entities and their repatriation roles. The entities are categorized by whether they are at the organization level of the university Office of the President, or the campus level. A solid or dotted line connects the entities to each other that can be either dotted or solid. Solid lines means that the entity has a reporting relationship to the entity it is connected to. Dotted lines means the entity has an advisory role to the entity it is connected to.

The first box above the flowchart explains that the Systemwide NAGPRA Policy establishes the responsibilities and requirements for the university’s compliance system that follow below.

Following this, the flow chart begins. Entities at the university Office of the President level are as follows:

The President of the university, who is the chief executive of the university and has responsibility for systemwide oversight and compliance.

Below the president, connected by a solid line indicating a reporting relationship, is the Research Policy Analysis and Coordination Office. The role of this office is to provide guidance and implementation assistance to campuses and other stakeholders regarding the development, interpretation, and implementation of university policies and external rules relating to the conduct of academic research.

Below the Research Policy Analysis and Coordination Office, connected by a solid line to the office indicating a reporting relationship, is the Systemwide Repatriation Coordinator. The systemwide coordinator provides support to campuses, reviews campus plans and budgets, and presents to the systemwide committee.

Connected solely to the President, with a dotted line representing an advisory role, is the Systemwide Committee. The systemwide committee is charged with providing compliance oversight and review, advising the President on matters related to the university’s implementation of NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA, and promoting the implementation of the systemwide policy.

Entities at the campus level are as follows:

Connected to the president with a solid line indicating a reporting relationship, are the campus chancellors. The campus chancellor is the executive head of a campus who has responsibility for oversight and compliance at the campus level.

Below campus chancellors, connected with a solid line indicating a reporting relationship, are campus repatriation coordinators. Campus repatriation coordinators are the individual designated by the chancellor at each campus with primary responsibility to conduct repatriation activity.

Below campus chancellors, connected by a dotted line indicating an advisory role, are campus committees. These campus committees are charged with providing compliance oversight and review, advising the Chancellor on matters related to the campus’s implementation of NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA, and promoting the campus level implementation of the systemwide policy.

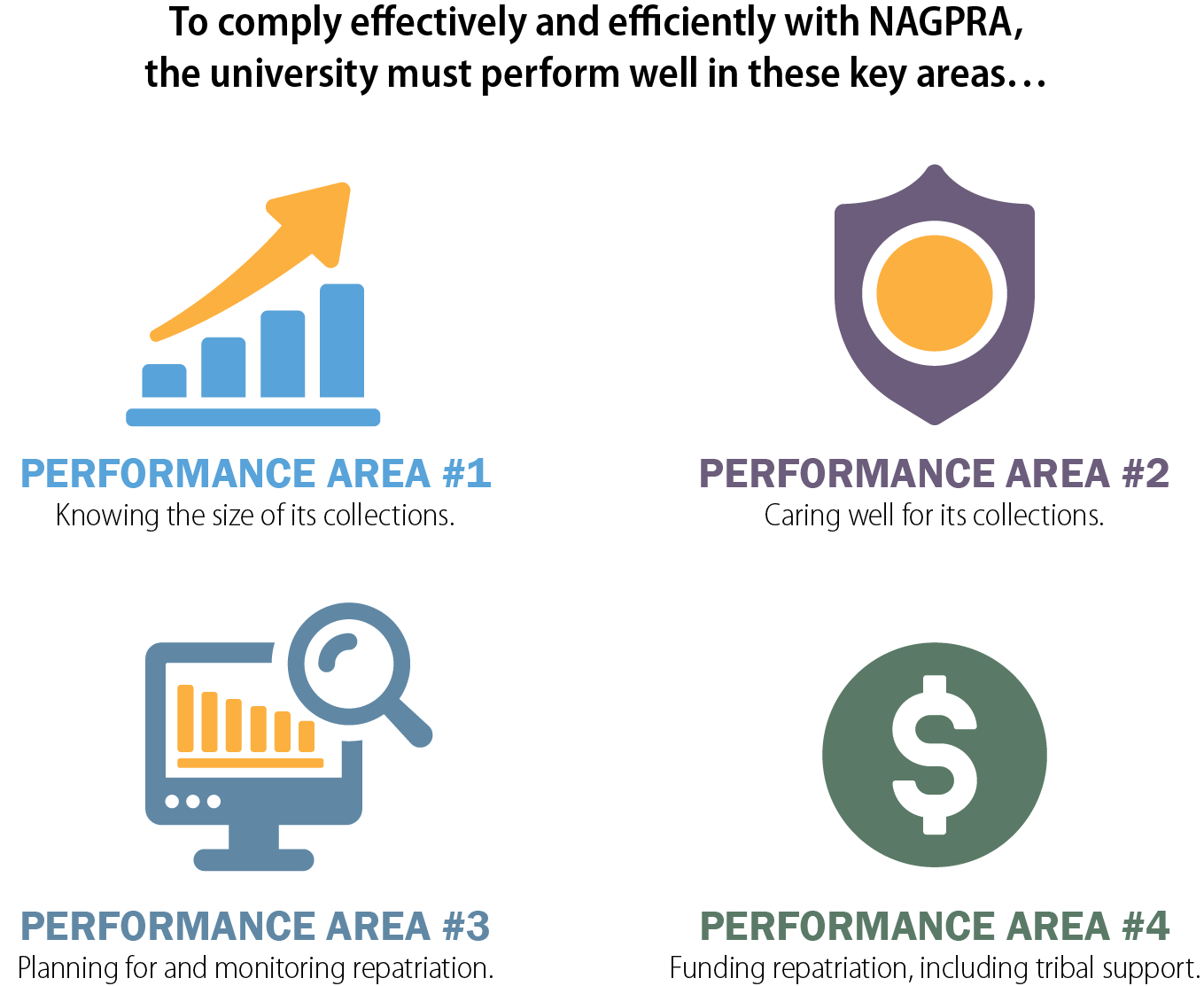

This audit is required under CalNAGPRA and is the third audit our office has conducted of the university’s compliance with NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA. To evaluate the university’s compliance with NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA, we conducted a detailed review of the NAGPRA processes at four university campuses with large collections: Berkeley, Riverside, San Diego, and Santa Barbara. Additionally, we conducted a more limited review at Davis for reasons that we discuss later in this report. Finally, we evaluated the oversight and guidance provided by the Office of the President. This report focuses on key areas in which the university must manage its operations effectively to ensure that it is effectively and efficiently complying with NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA. Figure 3 presents these key areas.

Figure 3

The University’s Compliance With NAGPRA Depends on Its Performance in Four Key Areas

Source: Auditor analysis of NAGPRA, CalNAGPRA, and the Green Book.

The figure shows a list of four key performance areas that the university must do well in to comply effectively and efficiently with NAGPRA, with corresponding icons. The key performance areas are:

1. Funding repatriation, including tribal support.

2. Knowing the size of its collections.

3. Caring well for its collections

4. Planning for and monitoring repatriation

Issues

Recent Changes to Federal Regulations Present Challenges to California’s Repatriation Goals

The University Does Not Know How Much Work Remains to Achieve Full Repatriation and Has Not Properly Cared For All Items It Possesses

Key Points

- Although the University of California (university) has made progress over the last five years, it continues to hold the human remains (remains) of thousands of individuals and hundreds of thousands of potential cultural items and will likely take more than a decade at its current pace to repatriate all of its collections.

- Campuses continue to experience discoveries of previously unknown collections. Despite the importance of having an accurate record of all Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) collections, the Office of the President has not required repatriation coordinators to search the entirety of their campuses for remains and potential cultural items.

- The university has not ensured the proper care and security of potential cultural items. As a result, the Santa Barbara campus still has outstanding loans of dozens of boxes of potential cultural items, some of which it loaned to graduate students, approximately 30 potential cultural items were stolen from the Davis campus, and three of the four campuses we audited do not have emergency management plans to protect storage spaces in the event of a natural disaster.

The University Continues to Hold the Remains of Thousands of Individuals and Hundreds of Thousands of Potential Cultural Items

Although NAGPRA’s requirements are decades old, the university continues to hold the remains of thousands of individuals and hundreds of thousands of potential cultural items. The university’s adherence to NAGPRA has been the focus of recent legislative hearings and audits. Accordingly, we examined the university’s performance in the five most recent calendar years to determine overall trends during a period of increased attention. Specifically, we reviewed two metrics: the number of repatriations completed and the number of notices the national NAGPRA program posted in the Federal Register from the university. Table 1 shows the results of that review and demonstrates that the campuses completed 100 repatriations from 2020 through 2024, 47 of which occurred since we published our previous audit report in November 2022. The pace of posts to the Federal Register and repatriations has increased at some campuses while remaining generally unchanged at others. For example, the national NAGPRA program posted only two notices from Riverside until 2023 and 2024 when it posted a combined 27 notices. However, the number of notices that the program posted from Berkeley each year was generally the same over the five-year period we examined.

Despite the university’s ongoing repatriation activity, campuses still have large collections of remains and potential cultural items. Campuses are required to offer to consult with tribes about these collections and, depending on various factors, may eventually need to repatriate them. As Table 2 shows, three of the four campuses we audited still possess the remains of hundreds of individuals and three of the four campuses each possess more than 100,000 potential cultural items.

A few things are important to note about the information we present in Table 2. First, the totals in the table include potential cultural items campuses reported holding. We include potential cultural items because they represent work the campuses must complete. Specifically, campuses must consult with tribes on these potential cultural items. Until campuses complete this consultation work, they will not know the true count of cultural items that they may need to repatriate. We provide more information about consultation and the work ahead of campuses in the next section of this report. After campuses have submitted notices for publication in the Federal Register, they have determined that the items in those notices are governed by NAGPRA and meet its definitions of cultural items. Accordingly, the data in Table 2 under the headers Posted to the Federal Register and Repatriated do not include potential cultural items.

Additionally, the unit of measurement for cultural items and potential cultural items is not uniform. Campuses may or may not count each individual item as a specific unit. Instead, because of tribal preference, the campuses may count units by box or lot, each of which could contain multiple items. Because CalNAGPRA requires campuses to defer to tribal recommendations for the handling and treatment of specified cultural items, we believe it is good practice for campuses to summarize their counts of cultural items as requested by tribes during consultation.

Finally, Table 2 shows the number of accessions or sites from which collections originate. An accession is a discrete collection added to a campus’s museum or repository, and a site refers to the geographic location from which collections were originally excavated. An individual accession or site can be associated with multiple remains or items. For example, one of the accessions that Santa Barbara repatriated included the remains of 14 individuals and 726 cultural items. Using collections data, we determined for each campus which metric—accessions or sites—would be best for measuring repatriation progress, and confirmed this determination was correct with each respective repatriation coordinator.

Measuring each campus’s repatriation progress by site or accession has some advantages over using solely the count of remains or items. Compared to remains or items, the number of each campus’s accessions or sites will likely fluctuate less over time, providing a more stable reference point for measuring progress. This is because one site or accession can be associated with multiple remains or potential cultural items. Each repatriation coordinator confirmed that measuring the number of accessions or sites a campus has repatriated against those it has not repatriated would enhance the understanding of the amount of work each campus must complete.

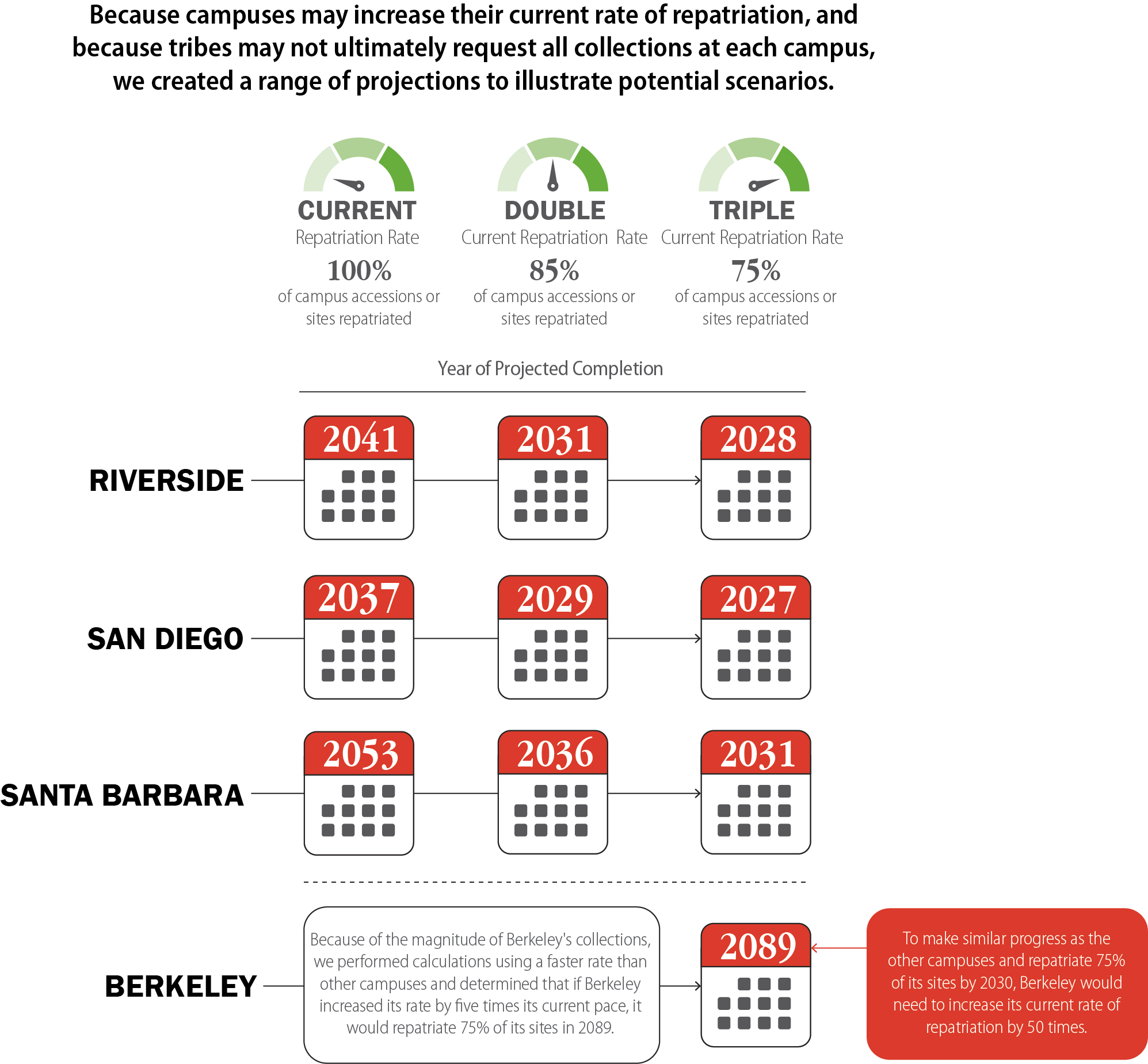

We used accession and site information to estimate when the campuses may complete repatriation. To do so, we reviewed the number of accessions or sites each campus repatriated from November 2022—the date our previous audit was published—through December 2024, and we used the resulting rate to project when each campus will complete repatriating all accessions and sites. As Figure 4 shows, the estimated date when campuses will complete repatriation depends on two main factors: the rate of repatriation and the percentage of the campuses’ collections that they will eventually repatriate.

Figure 4

Campuses Still Require Several Years to Repatriate Their Collections

Source: Campus collections data, repatriation records, and auditor projections.

The figure shows a range of projections to illustrate potential scenarios for how long it will take campuses to repatriate their collections. The projections show that it will take several years for each of the four campuses to repatriate their collections. Using the rate of repatriation at each campus, along with the percentage of campus collections repatriated, the following projections are shown:

Riverside, San Diego, and Santa Barbara, each have are three projections.

It will take Riverside until 2028 if it works at triple its current repatriation rate and repatriates 75 percent of its collections; 2031 if it works at double its current repatriation rate and repatriates 85 percent of its collections; and 2041 if it works at its current repatriation rate and repatriates 100 percent of its collections.

It will take San Diego until 2027 if it works at triple its current repatriation rate and repatriates 75 percent of its collections; 2029 if it works at double its current repatriation rate and repatriates 85 percent of its collections; and 2037 if it works at its current repatriation rate and repatriates 100 percent of its collections.

It will take Santa Barbara until 2031 if it works at triple its current repatriation rate and repatriates 75 percent of its collections; 2036 if it works at double its current repatriation rate and repatriates 85 percent of its collections; and 2053 if it works at its current repatriation rate and repatriates 100 percent of its collections.

Due to the magnitude of Berkeley’s collections, we used different parameters to calculate a projection. We determined that if Berkeley increased its rate by five times its current rate, it would repatriate 75 percent of its sites in 2089. A separate call-our box indicates that, to make similar progress as the other campuses and repatriate 75% of its collections by 2030, Berkeley would need to increase its current rate of repatriation by 50 times.

As we indicated earlier in this section, the rate of repatriation activity at some campuses has increased during the past five years. If that trend continues, those campuses would likely complete repatriation at an earlier date. Additionally, tribes may determine through ongoing consultation that NAGPRA does not govern the collections from an accession or site, which in turn would decrease the total number of accessions or sites from which the campus must repatriate collections. Moreover, campuses will need to repatriate collections from an accession or site only if they receive a repatriation claim from an affiliated tribe. Because federal regulations do not require tribes to submit claims, campuses ultimately may not repatriate collections from every known accession or site. Although it is not possible to account for these factors precisely, the scenarios we have modeled in Figure 4 identify a range of possible dates by which the campuses may complete repatriation activities and show that in several scenarios, the repatriation activity will last for at least the next five years.

Finally, we noted that the university posted to its website a dashboard of information about its repatriation progress as of May 2024. The dashboard shows information in a format similar to our presentation in Table 2. However, there are stark differences between the university’s presentation of its progress and the presentation we make in this report. Most significantly, the university’s presentation does not include potential cultural items. Because of that, the information on the university’s website presents a more positive view of the work the university has left to complete than is accurate. For example, the university’s website shows that, across the entire system, the university has still not repatriated about 108,000 cultural items. However, Table 2 shows that just among the four campuses we audited, there are hundreds of thousands more potential cultural items about which the university must consult with tribes before it knows whether the items are cultural items. Using Riverside as an example, Figure 5 shows the effect of this missing information. The university’s presentation of its remaining work is limited and potentially misleading.

Figure 5

The University’s Dashboard Presents Incomplete and Potentially Misleading Information About Campus Progress

Source: Office of the President dashboard and campus collections data.

A table is presented showing the university’s dashboard data for Riverside and the percentage of cultural items the campus has repatriated.

The university’s dashboard states that Riverside has repatriated 5,963 cultural items and has a total of 14,534 cultural items; beneath these numbers is a separate box stating: “The dashboard data for Riverside show that the campus has repatriated 41 percent of its cultural items.”

A call-out box on the 14,534 cultural items states: “But the dashboard does not disclose that Riverside also has more than 240,000 potential cultural items.”

There is a last textbox at the bottom of the figure that states, “The university’s dashboard provides no context for how much larger the collections of cultural items may become and how much more work the university must engage in.”

Further, the university does not make apparent to the readers of its website the disclosures we make here in this report about counting methods. Because it does not disclose that campuses may be counting cultural items in a summarized manner, the university’s dashboard could lead one to conclude, erroneously, that campuses are directly comparable in the number of cultural items they report in various stages in the repatriation process. Finally, the university has not shared information about the number of accessions or sites from which the remains or items originate. As we state above, this metric would be helpful to understanding the amount of work left for campuses to perform.

Through Consultation With Tribes, Campuses Will Likely Identify Additional Cultural Items They Possess That May Be Eligible for Repatriation

The four campuses we audited continue to consult with tribes about the remains and potential cultural items they possess. We reported in our November 2022 audit that both Riverside and San Diego had recently discovered large collections of remains and potential cultural items. As of this present audit, both campuses were still consulting with tribes on these collections, at least some for which the university has accepted responsibility. In addition, Berkeley’s repatriation coordinator stated that the campus is actively consulting on approximately 80 percent of the sites from which remains originated. She clarified that the campus will consult on the remaining sites once it hires and trains additional staff. Santa Barbara’s repatriation coordinator explained that the campus is still engaged in active consultation with tribes on remains and potential cultural items. We reviewed 10 total repatriation claims across the four campuses we audited to determine whether the campuses were consulting with tribes as part of the repatriation process and found in all cases that the campuses did so. These consultation efforts included invitations to consult that the campuses extended to California tribes.

Recent changes to NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA could make it more likely that tribes will identify as cultural items the potential cultural items that campuses possess. Although the definitions of cultural items in NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA have not substantively changed, both NAGPRA’s implementing regulations and CalNAGPRA have recently been amended to provide greater weight to tribal knowledge. Effective in 2021, the state amended CalNAGPRA to define tribal traditional knowledge as expert opinion, to include tribal traditional knowledge as a valid basis for establishing affiliation, and to indicate that tribes can make broad categorical identifications of items. For example, tribes may identify all items from a specific site as sacred objects because the site itself is sacred. Similarly, the 2024 amendments to NAGPRA’s implementing regulations require campuses to show deference to Native American traditional knowledge when complying with the regulations, which includes consulting with tribes about remains and cultural items the campus possesses, determining the items NAGPRA governs, the category of cultural item they fall under, and the tribe or tribes affiliated with these items. Tribal knowledge or tradition was evidence used to support the affiliation to a tribe in six of the 10 repatriations we reviewed, including all three of those we reviewed from Berkeley, which is a campus that tribes have historically found did not give appropriate weight to tribal knowledge or tradition.

As we describe in the Introduction, recent changes to NAGPRA’s implementing regulations require campuses to update inventories that they submitted to the federal government under specified circumstances. Although the reporting deadline included in this new requirement would not yet apply to the campuses we audited, repatriation coordinators at the campuses said they believe they will meet the deadlines in the new federal regulations. The consultation that campuses engage in will be essential to completing this work in line with the expectations established in the new regulations.

Santa Barbara Had Not Notified Tribes About All of Its Potential Cultural Items and Must Review Its Collections to Determine Whether More Have Gone Unreported

Before tribes are able to identify cultural items during consultation, campuses must first comply with critical notification requirements in NAGPRA and CalNAGPRA. NAGPRA requires campuses to submit to the national NAGPRA program a summary of the collections they possess that may contain unassociated funerary objects, objects of cultural patrimony, or sacred objects. Additionally, NAGPRA requires campuses to invite tribes to consult on potential associated funerary objects. CalNAGPRA contains similar requirements. By complying with these requirements, campuses are ensuring that tribes are aware of the collections that are available for their review. Because tribes can only request to consult on the potential cultural items of which they are aware, it is essential that campuses account for all potential cultural items in their possession and report this information as required.

During our review of campus collection data, we became aware that Santa Barbara had not fully complied with these reporting requirements. When we reviewed the data Santa Barbara provided related to its campus collections, we identified a data field that indicated whether an accession contained NAGPRA collections. However, many of the accessions that the campus’s data identified as having NAGPRA collections were not in the campus’s records of accessions it had reported to the national NAGPRA program or to the Native American Heritage Commission (NAHC). To better understand how to calculate the campus’s collection size, we asked Santa Barbara’s repatriation coordinator about these data. He explained his belief that the NAGPRA indicator in the data was unreliable. The repatriation coordinator strongly urged us not to use the NAGPRA indicator in the campus’s data to determine the size of the campus’s NAGPRA collections.

In response, we performed additional review of the campus data and then asked the repatriation coordinator to review specific accessions. In particular, we identified dozens of accessions from sites in California for which the campus’s data indicated that the campus had possession and that we could not find within the campus’s records of what it had reported to the national NAGPRA program or NAHC. These included accessions that the campus data indicated were NAGPRA-related and others that it did not. Among these accessions were two in which the items in the accession came from a site the campus has previously identified as a burial site—which indicates that the items from the site could be associated funerary objects. The campus identified this site as a burial site when it repatriated remains and associated funerary objects from that site. Therefore, these two accessions represent additional potential cultural items from the same site that the campus did not notify the tribe about through a report to the national NAGPRA program or the NAHC, nor returned at the time of that repatriation.

We selected five of the accessions we identified, all of which were cases that the campus’s data indicated the accessions contained NAGPRA collections, and we shared those data with the repatriation coordinator for his review. After reviewing those accessions, the repatriation coordinator stated that the five accessions should have been included in the campus’s summaries and reported to us that he updated the summaries to include these accessions after we brought them to his attention. Given that the accessions we presented to the repatriation coordinator were only a small subset of the dozens of potentially excluded accessions we identified, many of which the campus’s own data indicate are related to NAGPRA, the campus does not have assurance that it has accurately reported all of the potential cultural items that it possesses.

Until the campus performs a thorough review of its collections to assess whether its summaries are complete, it is likely that tribes will have an incomplete understanding of all collections from Santa Barbara that should be available for consultation. This is especially troubling because Santa Barbara has historically had difficulty in understanding the span of its collections. As a part of our November 2022 audit of the university, we reported that we were unable to gain assurance about the size of Santa Barbara’s collection because that campus had only recently committed the resources necessary to review all of its collections. Although the campus has made significant progress in the past two years by reporting many accessions to the NAHC, we have found again that the campus must perform additional work to fully understand the span of its NAGPRA collections. Specifically, Santa Barbara must review each of its collections to determine whether the campus should report the collection to the national NAGPRA program and to the NAHC. As we were finalizing our report, Santa Barbara’s repatriation coordinator indicated that he had begun this type of review.

The Office of the President Has Not Ensured That Campuses Proactively Search for Undiscovered Remains and Items

The information we present earlier in Table 2 is the best available information as of the time of our audit about the campuses’ known remains and items. However, undiscovered collections of remains and potential cultural items may eventually cause the campuses’ collection sizes to grow. Undiscovered collections are those that are located on the campus—and that the campus may have legal responsibility for—but about which campus NAGPRA staff are unaware. For example, in our November 2022 audit, we reported that both Riverside and San Diego had recently discovered large collections that campus NAGPRA staff had been previously unaware of. In some cases, certain members of campus faculty had not reported these collections to the campuses. Figure 6 summarizes our concerns about the university’s approach to finding undiscovered collections.

Figure 6

The University Does Not Know the Full Extent of Its NAGPRA Collections

Source: NAGPRA, documentation from the campuses we audited, interviews with repatriation coordinators, and the systemwide policy.

The figure shows a text box in the top of the graphic that says “Performance Area #1: Knowing the Size of its Collections.” This refers to figure 3, displayed earlier in the report, which states the four performance areas the university must do well in to comply effectively and efficiently with NAGPRA.

Under the “Performance Area #1” text box, there are four text boxes with accompanying images that summarize how the University does not know the full extent of its NAGPRA collections.

The first text box states, “Since NAGPRA was first passed in 1990, agencies and museums have been expected to know the extent of their NAGPRA collections.”

The second text box states, “Despite having more than 3 years to determine their collection sizes, campuses are still discovering previously unknown collections of remains and potential cultural items.”

The third text box states, “The Office of the President has not systematically tracked the searches campuses are required to perform, and campuses have not finished searching.”

The fourth text box states, “As a result, the university has continued to see its known collection sizes grow.”

Searching for undiscovered collections is of significant importance to tribes. For instance, one tribe we spoke with expressed concerns that museums’ historically poor recordkeeping has resulted in these museums having remains and cultural items without knowing of their existence or present location. This tribe explained that it believes the Office of the President should take a systemwide approach to locating undiscovered collections. Another tribe described how it is common for tribes to consult with campuses, and then for campuses to subsequently discover additional unknown remains and cultural items, which is an issue that this tribe reported experiencing when consulting with Riverside. Additionally, in January 2023, one tribe wrote a complaint letter to the university’s president expressing its concern that Berkeley had not located remains that the campus had recorded as belonging to the tribe but that were currently missing. These concerns from NAGPRA’s primary stakeholders illustrate the importance of conducting searches of campuses for any remains or potential cultural items that may be subject to NAGPRA.

Since publishing our previous audit of the university’s NAGPRA compliance in November 2022, three of the four campuses we audited as a part of this audit—Riverside, San Diego, and Santa Barbara—reported new discoveries of previously unreported collections. Riverside’s repatriation coordinator discovered the remains of one individual in a campus lab after receiving a report from the biology department. The same repatriation coordinator also found at least 10 potential cultural items at the anthropology department. At Santa Barbara, the campus repatriation coordinator conducted a review of the anthropology department’s teaching laboratory and discovered approximately 1,500 potential cultural items. In addition, the same campus also identified other collections that included remains a professor had not previously brought to the campus’s attention. Finally, San Diego’s repatriation coordinator confirmed that in November 2024, she removed remains and potential cultural items from the office of a recently deceased faculty member after receiving a report about the presence of these items.

Despite these discoveries and the continued risk that undiscovered collections present, the Office of the President has not established the accountability necessary to ensure that campuses identify all collections. We reviewed the steps the Office of the President has taken to set expectations for how campuses should identify their undiscovered collections, the actions the campuses have taken to try and address this issue, and how the Office of the President has responded to campus reporting about undiscovered collections.

The university’s systemwide NAGPRA policy (systemwide policy) requires campus NAGPRA staff to complete two steps to identify undiscovered collections. First, it requires that, every three to five years, campus repatriation coordinators search departments that have historically engaged in studies that could result in the intentional or unintentional collection of remains or cultural items (high risk departments). The policy provides the examples of anthropology, biology, or history departments, among others. Secondly, the systemwide policy requires all academic departments to self-report through a periodic survey whether they hold any remains or potential cultural items. Repatriation coordinators must then search departments that report holding remains or potential cultural items.

However, despite the requirement to search high risk departments, campuses have not finished searching, with three of the four campuses we audited indicating that they have more departments to review before they locate all NAGPRA collections. San Diego has conducted no proactive searches of campus departments since our previous audit. San Diego’s campus repatriation plan established a goal of searching the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) by the end of 2023 due to its risk for housing potential cultural items. The SIO is a large portion of campus property, featuring more than 30 buildings. However, the campus repatriation coordinator confirmed during our audit in late 2024 that she is waiting until the campus hires additional NAGPRA staff, after which she will conduct the search of SIO. Of additional concern, the repatriation coordinator stated that available evidence indicates the presence of potential cultural items at SIO; however, the repatriation coordinator indicated that she has yet to conduct proactive searches because of limited bandwidth. She also expressed concern about the sensitivity of searching spaces that some academics may consider to be private spaces.

Berkeley and Riverside have conducted only a limited number of proactive searches of campus departments when compared to the number of locations on campus that must be searched. Berkeley’s repatriation coordinator reported that the campus has conducted searches of four departments, but also acknowledged several additional spaces—such as the anthropology building—must be searched before gaining additional assurance that she has located all collections. Similarly, Riverside has conducted two proactive searches of departments, in addition to responding to reports of remains in specific areas on campus. However, Riverside’s repatriation coordinator provided a list that indicated that she plans to conduct searches in several other campus departments. The coordinator emphasized the importance of doing so; she explained that she has found undiscovered collections in areas of the campus that were completely unexpected. Similarly, our previous audits of the university’s compliance with NAGPRA—as well as the examples of campus discoveries that we describe earlier in this section—suggest that campuses have not kept accurate records about where NAGPRA collections are located, highlighting the need for campus-wide searches.

Staff at Santa Barbara have conducted three reviews of campus locations, and one of those searches resulted in the discovery of potential cultural items. Specifically, Santa Barbara’s repatriation coordinator reported to us that he conducted a search of teaching laboratories in the campus’s anthropology department in response to both his own personal knowledge of the potential for collections to be located there and also in response to a report from a professor. His search resulted in the discovery of approximately 1,500 potential cultural items. The repatriation coordinator stated that he has no plans to conduct further inspections. He considers anthropology the only department at high risk for holding undiscovered collections.

The repatriation coordinators at some of the campuses we reviewed explained that they have faced barriers when attempting to conduct searches. For example, both Berkeley and San Diego’s repatriation coordinators explained that they have had limited bandwidth to proactively search high risk departments. More significantly, some repatriation coordinators have described instances in which they have faced resistance when trying to conduct searches. Riverside’s repatriation coordinator explained that one department on campus has not responded to multiple requests to schedule a search, an issue that she ultimately referred to the campus compliance office. Berkeley also noted some resistance from one department it reviewed. Repatriation coordinators from three campuses also explained that additional action from the Office of the President—such as releasing a stronger statement that departments must comply with NAGPRA, or providing additional guidance, such as a checklist outlining important steps in the search process—would be helpful. Additionally, one repatriation coordinator explained that having a dedicated individual at the systemwide level to assist with searches would help support campus efforts.

We asked the Office of the President about its oversight of campuses searches and found that the office has not systematically kept track of the searches campuses perform to ensure compliance with the systemwide policy. Specifically, at the outset of our audit, the systemwide repatriation coordinator and a director in the Office of the President’s Research Policy Analysis and Coordination Office (research director) indicated they were aware of some searches that had occurred at certain campuses, but that they did not maintain lists of departments that need to be searched for each campus and thus they did not know how many additional searches needed to be conducted. Pursuant to the systemwide policy, campuses do report on the locations reviewed and materials found in their biannual reports to the Office of the President. However, because the Office of the President does not require campuses to provide a list of departments that repatriation coordinators have identified as needing review, it is not able to monitor the campuses’ progress toward completing all necessary reviews.

Because campus searches have not progressed as expected by the systemwide policy, the second requirement in the policy—surveys of all departments to collect self-reported accounts of potential NAGPRA collections—takes on greater importance because it could more quickly alert NAGPRA staff to any collections. However, the survey approach is marked by key weaknesses. First, this approach depends heavily on the survey respondents to disclose remains and potential cultural items. Historically, the university has had cases of faculty and other individuals who have not reported collections. For example, the discovered collections from Riverside and San Diego described in our November 2022 audit report involved employees who did not disclose these collections to the campuses. In another example, a professor at Santa Barbara disclosed to a tribe that she held remains but had not reported those remains to the campus directly.

Secondly, survey respondents may lack the knowledge or expertise necessary to know when they possess reportable collections. Although the systemwide policy requires campus chancellors to annually communicate with relevant faculty, researchers, students, and staff to raise awareness about NAGPRA’s requirements, we found that three of the four campuses we audited did not send out this communication as required. Santa Barbara did not send out the required communication in 2023, meaning it went about 22 months between communications. San Diego did not send out the required communication in 2022. Additionally, before its December 2024 communication, Riverside had most recently sent out its annual communication in 2022. Campuses’ failure to routinely educate members of their community regarding NAGPRA’s requirements likely degrades the effectiveness of having faculty and staff self-report collections.

Finally, some campuses received low response rates to the surveys they distributed. Riverside and San Diego noted receiving low response rates when they sent out their first survey, and they had to take additional steps in an attempt to receive more responses. Additionally, we found that Santa Barbara recorded receiving survey responses from only two departments, despite having distributed the survey across the entire campus.

When asked about the survey’s low response rates at some campuses, the university’s systemwide repatriation coordinator explained that the Office of the President was not surprised, given the size of the campuses and that the majority of departments likely do not have remains or potential cultural items. However, the systemwide policy clearly states that all departments must respond to the survey. Further, at an August 2021 legislative oversight hearing, the university assured the Legislature that campus-wide searches would occur. Consequently, it is unclear why campuses and the Office of the President have not taken further action to make sure all departments follow the requirements outlined in the systemwide policy.

We also noted that the Office of the President has not responded to reports from the campuses about their low survey response rates. The template for the campuses’ biannual reports to the university’s systemwide NAGPRA committee (systemwide committee) and to the Office of the President asks campuses to list the departments or units to which they distributed the NAGPRA survey. Additionally, the biannual report asks campuses to detail their efforts to receive a response when a department or unit fails to respond. In multiple biannual reports, Riverside has reported low survey response rates. The biannual report covering the January through June 2024 period lists the campus as having a response rate of only 37 percent, more than two years after the campus distributed the survey. Santa Barbara reported to the Office of the President that it received responses from only two departments after distributing the survey campus-wide, which the campus website indicates includes at least 60 departments. However, repatriation coordinators from three of the four campuses we audited stated that they have received little or no feedback from the Office of the President regarding the information they include in their biannual reports. Given that the effectiveness of the survey relies on receiving responses, we find it concerning that the Office of the President did not take action after campuses reported low response rates.

The university must take a more systematic and proactive approach to searching for undiscovered remains and potential cultural items. Presently, the university is at risk that faculty and staff will—knowingly or unknowingly—fail to report collections. Until the university takes additional steps, including increasing the level of oversight performed by the Office of the President, it will continue to jeopardize its ability to have a complete understanding of the remains and potential cultural items it holds.

The University Has Not Properly Cared for All Items in Its Possession

In recent years, state law, federal regulations, and university policy have all increased expectations for how campuses handle and store the remains and cultural items in their possession. The text box summarizes the ways in which the university can properly handle and store NAGPRA collections. As of January 1, 2019, the State required that the university adopt systemwide policies regarding the culturally appropriate treatment of remains and cultural items as a condition for using state funds to handle those remains and items. Following that, in 2020 the State again amended CalNAGPRA and as of January 1, 2021, required all agencies and museums in possession of specified cultural items to defer to tribal recommendations for appropriate handling and treatment of those items. In January 2022, the university’s systemwide policy took effect and created additional expectations for the appropriate handling of remains and cultural items. Specifically, the policy required that campuses treat remains and cultural items in a respectful manner, specified that they would consult with tribes about handling preferences, and permitted only authorized individuals access to remains and cultural items. Finally, in January 2024, new federal regulatory requirements took effect, which require, among other things, the campuses to consult with tribes on the appropriate storage, treatment, and handling of remains or cultural items and to obtain free, prior, and informed consent before exhibiting or allowing access to remains and cultural items.

Examples of Proper Care and Storage Practices

- Minimize handling and only inspect or move collections as recommended or requested by tribes

- Consult with tribes on appropriate storage conditions

- Securely store collections in spaces where access is limited to only designated individuals

- Ensure storage spaces contain fire detection and suppression systems

- Establish emergency management plans for storage space

Source: Systemwide policy, NAGPRA, CalNAGPRA, and interviews with repatriation coordinators.

Some steps the university has taken demonstrate how it has appropriately cared for its collections. In November 2022, we reported that both Riverside and San Diego had recently discovered large, previously unknown collections of remains and potential cultural items that had been stored in inappropriate locations. However, during this audit, we visited Riverside and San Diego and observed that the collections spaces appeared appropriate for storing remains and potential cultural items. Specifically, the spaces were secure and contained fire suppression equipment. Moreover, across the four campuses we audited, we reviewed a selection of 10 completed repatriation claims. The documentation related to these claims or other documentation that campuses provided, demonstrated that the campuses knew about the respective tribes’ handling preferences.

Despite these steps, we also found two instances in which the university has not appropriately cared for potential cultural items. As part of our audit, we reviewed the biannual reports that campuses submit to the Office of the President detailing their repatriation activities. Within those biannual reports, we identified concerning circumstances related to the handling of potential cultural items. Figure 7 summarizes our concerns.

Figure 7

The University Has Not Taken Sufficient Action to Protect Potential Cultural Items

Source: Campus biannual reports, interviews with repatriation coordinators, and the systemwide policy.

The figure shows a text box in the top of the graphic that states “Performance Area #2: Caring well for its collections.” This refers to figure 3, displayed earlier in the report, which states the four performance areas the university must do well in to comply effectively and efficiently with NAGPRA.

Under the “Performance Area #2” text box, there are four text boxes with accompanying images that summarize how the University has not taken sufficient action to protect potential cultural items.

The first text box states, “If the university does not properly care for the potential cultural items it holds, they could be damaged or disrespectfully stored.”

The second text box states, “In 2022, approximately 30 potential cultural items from burial sites were stolen from the Davis campus.

The third text box states, “Over the last two decades, Santa Barbara has loaned dozens of boxes of potential cultural items that it has not yet retrieved. Some are now located outside of the State.”

The fourth text box states, “The university’s systemwide policy does not clearly specify how campuses should handle or store most types of potential cultural items.”

We found one of those instances at Santa Barbara, where the campus has not retrieved several outstanding loans of potential cultural items. Santa Barbara is aware of items from 10 accessions that it has loaned during the past two decades and never received back. The items from these accessions were stored in dozens of boxes, some of which were loaned to graduate students, and at least some of which are now located in a different state. The biannual report the campus submitted to the Office of the President about its NAGPRA activity in the first six months of 2024 indicates that these loans were for research purposes and that the campus made the most recent of these loans in 2013.

Santa Barbara’s repatriation coordinator stated he has not notified tribes that the campus has outstanding loans or that the potential cultural items are not currently stored at the Santa Barbara campus. He planned for the campus to notify tribes about the loan status once the tribes expressed an interest in consulting with the campus about those items, and he conveyed his belief that there was a very good chance the campus would retrieve these loaned items before the tribes want to consult. However, for two of Santa Barbara’s outstanding loans, the campus’s records do not show that it reported the accessions to the NAHC as required by CalNAGPRA, meaning it is unlikely that the tribes know to ask to consult on these loaned accessions. Although the biannual report indicates that the campus has made contact with some of the individuals who possess the loaned items, Santa Barbara’s repatriation coordinator indicated that he has not had the bandwidth to work on retrieving outstanding loans. He also explained that none of the loaned collections include remains, which he is prioritizing his work around. However, because Santa Barbara has not yet retrieved these loans, the campus has no assurance that the potential cultural items are being stored respectfully or securely.

The Office of the President indicated that recalling outstanding loans may be challenging because of incomplete or unreliable campus records on loans, difficulty locating the individual in possession of the loan, and the potential need for campuses to conduct additional research. Nonetheless, we believe that the university would best ensure the security of the potential cultural items it has legal responsibility for if it retrieved all of the items it has loaned, with one notable exception: tribal preference to leave the loaned items at their current location. Some tribes may prefer to minimize handling of these items, in which case the university should abide by those preferences.

An incident at Davis illustrates the importance of secure storage. In a biannual report to the Office of the President on its repatriation activities, Davis detailed how, in February 2022, approximately 30 potential cultural items were stolen from a display case in a campus lecture hall. According to the campus’s report, the stolen items originated from sites about which the campus had not fully consulted with tribes. Further, although the campus had not initially identified those items as funerary objects, the sites they came from included burials. Davis’s repatriation coordinator stated that the campus had not removed the items from the display case because the campus had yet to consult with tribes to determine whether they were cultural items as defined by NAGPRA.

The campus’s approach has now resulted in the loss of these potential cultural items and the likelihood that the campus will never be able to return them to the tribe or tribes to which they belonged. Davis’s repatriation coordinator explained that, in response to the theft, the campus notified tribes about the incident and removed all remaining California collections from the lecture hall where the theft occurred. The repatriation coordinator also provided emails demonstrating that she contacted the managers of another area of campus, which may have been at similar risk of theft incidents, to warn them.

Davis’s treatment of the stolen potential cultural items was not a clear violation of the systemwide policy. The systemwide policy directs that campuses’ consultation with tribes should include discussions about tribes’ handling preferences, but does not otherwise establish explicit minimum handling or storage requirements for potential cultural items in the same way it does for remains and confirmed cultural items. Further, in November 2023, while responding to a recommendation from our previous audit, the Office of the President issued guidance to campuses regarding the handling and storage of newly discovered potential cultural items. However, the guidance is limited to only new discoveries. As we explain earlier, campuses are still consulting with tribes about potential cultural items they already know they possess, and the outcome of that consultation can be the identification of cultural items among objects that, until the consultation, the campus had only defined as potential cultural items. Therefore, the university should establish clear minimum storage and handling requirements for all potential cultural items. As demonstrated by the incident at Davis, campuses that do not take steps to securely store all potential cultural items are taking inadvisable risk that the items will be damaged or lost, precluding the campuses’ ability to return them to the tribes to which they belong.

In addition to concerns regarding the security of its collections, we found another shortcoming in the university’s plans to safeguard remains and associated funerary objects. The university’s systemwide policy requires campuses to adhere to specified federal standards for the storage spaces in which the campuses keep remains and associated funerary objects, standards that are not explicitly required by NAGPRA or CalNAGPRA. Among these federal standards is the requirement to have an appropriate and operational fire detection and suppression system and a requirement to have an emergency management plan for responding to events such as natural disasters. The four campuses we audited provided evidence of having a fire suppression system. However, only Berkeley had an emergency management plan. Campuses are more at risk of remains and cultural items being damaged or destroyed in the event of an emergency because of their lack of planning for disasters or emergencies.