2023-130 Conditional Release Program for Sexually Violent Predators

Program Participants Are Less Likely to Reoffend, While the State Has Difficulty Finding Suitable Housing

Published: October 15, 2024Report Number: 2023-130

October 15, 2024

2023‑130

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the Department of State Hospitals’ (DSH) Sexually Violent Predator (SVP) Conditional Release Program (program). In general, we found that individuals who participated in the program were convicted of new offenses less often than were SVPs who were unconditionally released from a state hospital and did not participate in the program. In fact, only 4 percent of program participants reoffended after their release from a state hospital, whereas 19 percent of nonparticipating SVPs reoffended.

We found that DSH has faced significant hurdles when attempting to place program participants into the community. These hurdles include a variety of factors such as complex program requirements, few property owners who are willing to rent for the purpose of the program, and public opposition to the placement of program participants within local communities. On average, it has taken the State 17 months to place program participants into the community.

We also reviewed administrative aspects of DSH’s oversight of the program. DSH has taken steps to ensure that its contractor, Liberty Healthcare, is effectively performing its responsibilities to administer many aspects of the program and to provide treatment and supervision services. However, DSH does not have an effective oversight process to track and monitor Liberty Healthcare’s implementation of the recommendations that result from its reviews. Consequently, DSH has allowed several known deficiencies to persist since at least 2019 without holding Liberty Healthcare accountable for implementing timely resolutions.

Regarding the program’s costs, we found that they have increased significantly, growing from $6.6 million in fiscal year 2018–19 to $11.5 million in fiscal year 2022–23. Finally, we developed recommendations to improve DSH’s administration of the program. For example, to potentially reduce the time needed to place program participants in housing in the community, we recommend that DSH analyze the benefits and feasibility of establishing transitional housing for participants in the program.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| CONREP | California Forensic Conditional Release Program |

| DSH | Department of State Hospitals |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| RFI | requests for information |

| SVP | sexually violent predator |

Summary

Results in Brief

California designates individuals who are convicted of specific sexually violent crimes and who also have significant mental health conditions as sexually violent predators (SVPs). When these individuals are nearing the end of their prison terms, a county Superior Court (court) may civilly commit them for an indefinite period to a state hospital for mental health treatment under the care of the Department of State Hospitals (DSH). DSH also administers the SVP Conditional Release Program (program). The program provides a means of transitioning individuals (program participants) who have been committed to a state hospital as SVPs back into the community after a court has determined that they qualify for treatment in a less restrictive outpatient environment. Since the program’s inception in 2003, it has placed 56 program participants into the community and provided services such as treatment and supervision. During this time, the State has contracted with a single vendor, Liberty Healthcare, to provide the program’s services.

Individuals Who Participate in the Program Reoffend Less Often Than Those Who Do Not Participate

Individuals who participated in the program were convicted of new offenses less often than were SVPs who were unconditionally released but did not participate in the program (nonparticipating SVPs). Of the 56 program participants placed into the community in the past 21 years, two were convicted of criminal acts, which they both committed while in the program. One conviction was for possessing child pornography, and the other conviction related to a violation of a reporting requirement for sex offenders. In contrast, of the 125 nonparticipating SVPs whom the courts unconditionally released from DSH’s custody since 2006, 24 were convicted of subsequent criminal acts. These convictions included 42 felony convictions, of which two were for sexually violent offenses and five were for offenses of a sexual nature. Six of these nonparticipating SVPs were convicted of felonies for multiple incidents.

DSH Has Faced Significant Hurdles When Attempting to Place Program Participants Into the Community

State law generally requires DSH to place program participants into housing in the community within 30 days of a court ordering their participation in the program. However, DSH has faced numerous hurdles when attempting to locate suitable housing for the program to use. These hurdles include complex program requirements intended to ensure public safety, few property owners who have been willing to rent for use by the program, and public opposition to the placement of program participants within local communities. Consequently, placing program participants has typically taken the State an average of 17 months, significantly longer than state law generally allows.

DSH Can Improve How It Monitors Liberty Healthcare’s Administration of the Program

DSH has taken certain steps to ensure that Liberty Healthcare effectively performs its contracted responsibilities. Specifically, DSH has performed scheduled reviews of Liberty Healthcare four times a year, and it conducted a more thorough program review in 2019. However, DSH has not had an effective oversight process to track and monitor Liberty Healthcare’s implementation of the recommendations from its reviews, and consequently, DSH has allowed several known deficiencies to persist since at least 2019 without holding Liberty Healthcare accountable for implementing timely resolution. Nevertheless, when we tested a selection of 10 out of 19 program participants in the community as of April 2024, we found that Liberty Healthcare had generally provided these individuals with the required services we evaluated in accordance with the number of services required by participants’ levels of care.

The Costs to Administer the Program Have Significantly Increased

The State’s cost to administer the program has increased from $6.6 million in fiscal year 2018–19 to $11.5 million in fiscal year 2022–23. The majority of these expenditures have related to DSH’s annual payments to Liberty Healthcare, which grew from $5.3 million to $9.4 million. A number of factors have contributed to the increased cost of DSH’s contract with Liberty Healthcare, including an increase in the number of program participants and a rise in California’s rental housing prices. DSH has not been successful in obtaining bids to perform program services from any vendor other than Liberty Healthcare since the program began in 2003, although DSH has made at least four attempts to seek such bids.

Agency Comments

DSH agreed or partially agreed with most of the recommendations we made and stated concerns or offered additional perspective on several of our conclusions. However, DSH disagreed with our recommendation to conduct an analysis of the benefits and feasibility of establishing transitional housing facilities for the program because it believes that transitional housing ultimately could further delay placement of individuals in the community.

Introduction

Background

The Department of State Hospitals (DSH) manages California’s state hospital system. This system provides mental health services to individuals whom a Superior Court (court) has committed for treatment. DSH also administers the California Forensic Conditional Release Program (CONREP), which provides treatment and supervision to certain individuals whom courts have released with various restrictions and conditions from state hospitals.

Beginning in 1996, legislation designated individuals with mental health conditions who are convicted of certain crimes as sexually violent predators (SVPs), and the law allowed the court to civilly commit such an individual to a state hospital for confinement and treatment for an indeterminate length of time. Courts that have committed SVPs to the state hospital system can subsequently place those individuals into the SVP Conditional Release Program (program)—a subset of CONREP that focuses specifically on treating SVPs in the community. DSH’s administration of the program is the focus of this audit.

Identification, Treatment, and Conditional Release of SVPs

When individuals who have been convicted of specific sexually violent offenses are nearing the end of their prison terms, the State must determine whether they meet the definition of an SVP and whether additional treatment is necessary before releasing them from custody. As Figure 1 shows, before such an individual’s release from the state prison system, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (Corrections) performs a preliminary screening to determine whether the individual is likely to be designated as an SVP. If so, Corrections refers the individual to DSH, which in turn conducts an evaluation to determine whether the person does, in fact, meet the definition of an SVP. This evaluation includes an assessment of the individual’s mental history and risk factors associated with reoffense.

Figure 1

The Process of Identifying, Treating, and Releasing SVPs

Source: State law.

Figure 1 shows the process of identifying, treating, and releasing SVPs. It begins when an individual is convicted of a particular type of sexually violent offense and has been sentenced to a prison term, and shows when DSH has custody of the individual and the decisions the court makes in regards to the individual’s participation in the program.

If DSH finds that an individual meets the definition of an SVP, it must request that the district attorney or counsel for the county that convicted the individual petition the court to review his or her possible designation as an SVP. The court holds a hearing that may be followed by a trial to reach a determination. If the court concludes that the individual is not an SVP, it orders him or her to be released at the conclusion of his or her prison sentence. If the court determines the individual is an SVP, it orders him or her into a civil commitment for an indeterminate length of time in a secure facility designated by the Director of State Hospitals until the court determines that the individual can be released.

DSH typically commits SVP patients to Coalinga State Hospital in Fresno County. State law requires that DSH offer these patients mental health treatment. If SVP patients refuse treatment, DSH must continue to offer treatment on at least a monthly basis. State law also requires that DSH evaluate SVP patients annually to determine whether they might qualify for release. As part of its evaluations, DSH may determine that SVP patients qualify for a less restrictive outpatient environment and may recommend conditional release through the program. SVP patients may also petition the court to participate in the program or to be unconditionally released with or without DSH’s recommendation.

If SVPs participating in the program (program participants), develop new or worse psychiatric symptoms or they do not comply with the terms of the program, the court can revoke their outpatient status and return them to a state hospital. Such individuals will remain in a state hospital until the court finds that they no longer pose danger to the health and safety of others and are not likely to engage in sexually violent criminal behavior if released either conditionally or unconditionally. However, all individuals whom a court has designated as SVPs must register as sex offenders either when unconditionally released from the state hospital system or when conditionally released and participating in the program.

The SVP Conditional Release Program

The State formally implemented the program in 2003. According to DSH’s CONREP Operations Manual (operations manual), the primary mission of the program is to protect the public through the reduction or prevention of reoffenses by individuals who have been identified as SVPs. Since the program’s inception, DSH has contracted with Liberty Healthcare, a health care services company, to provide outpatient mental health treatment, supervision, and assessment services to program participants. The text box summarizes the program’s core services, and Appendix B describes the services in greater detail.

Core Clinical Treatment Services

- Forensic individual contact (therapy)

- Group contact

- Home visit

- Collateral contact

- Substance use screening

- Annual case review

- Dynamic risk and personality testing assessments

- Polygraphic assessment

- Sexual interest screening or sexual arousal assessment

- Global Positioning System (GPS) data review

Source: DSH’s contract with Liberty Healthcare and DSH’s operations manual.

To effectively transition program participants from the state hospital setting to the community, DSH works with Liberty Healthcare to locate housing in the county where the court has determined that a program participant may reside. Liberty Healthcare is responsible for finding and assessing possible placement locations, reviewing the locations with DSH staff and local stakeholders, and renting the selected property. To find an appropriate location, Liberty Healthcare must take into consideration a program participant’s profile of risk factors and reintegration needs, as well as residency restrictions and other factors related to community and patient safety. For example, state law prohibits program participants convicted of committing certain crimes against minors from residing near schools. DSH does not place a program participant in the community setting until a court determines that the placement location is appropriate.

Once program participants are placed in housing, Liberty Healthcare provides them with treatment and monitoring in their residences or at designated locations. DSH structures community outpatient treatment according to levels of care that reflect program participants’ levels of functioning and specific treatment and supervision needs. The text box describes the program’s three levels of care. This structure allows Liberty Healthcare to develop an individualized treatment plan for each program participant that reinforces positive behavioral changes directed toward a goal of eventual unconditional release from DSH’s care and that prepares the participant for this release. Ideally, program participants steadily and sequentially progress from one treatment level to the next until the court determines that they can be unconditionally released from DSH oversight. Liberty Healthcare applies treatment goals and outcome standards to program participants according to their assigned level of treatment.

Community Outpatient Treatment Levels for Program Participants

Phase I: Intensive Level—This level is appropriate for patients who recently have been admitted to community treatment, demonstrate problems adjusting to community life, or have been assessed at the highest acceptable level of risk.

Phase II: Supportive Level—This level is appropriate for moderate risk patients who have made demonstrable progress, are not considered ready for unconditional release, and need ongoing program services for an indefinite length of time.

Phase III: Transitional Level—This level is appropriate for patients who have progressed through the other treatment levels and are being considered for unconditional release.

Source: DSH’s operations manual.

DSH and Liberty Healthcare assess program participants’ progress toward their treatment plan goals and develop the individual terms and conditions that program participants must follow in order to participate in the program. Appendix C presents examples of these terms and conditions. Some general provisions apply to all program participants, such as travel restrictions and GPS monitoring requirements. Other personalized provisions may apply only to specific individuals, such as requirements related to substance use treatment and support groups. Program participants must work toward their treatment plan goals and abide by their placement terms and conditions to remain in the program.

DSH has established a number of program requirements to ensure public safety. DSH relies on Liberty Healthcare to implement most of these requirements. For example, Liberty Healthcare performs scheduled and unscheduled home visits with program participants and monitors their locations using a GPS tracking system. Liberty Healthcare also performs substance use screenings and conducts polygraph examinations that it may use as rationale for increased supervision and surveillance if it determines that a program participant has violated program requirements or has been deceptive.

Certain elements of state law also address public safety. For example, state law establishes a revocation process to reduce the risk that program participants will commit crimes while in the program. If program participants violate program requirements or start to exhibit risky behaviors, DSH or the county district attorney may petition the court to order those participants returned to a state hospital for an indeterminate length of time. Examples of program requirement violations and risky behaviors include program participants repeatedly missing counseling appointments or obtaining or using prohibited substances. After a revocation, such patients may again petition the court to participate in the program.

The State’s and County Governments’ Participation in the Program

Under state law, DSH is responsible for administering and overseeing the program, for locating housing in the community for program participants, and for providing treatment and supervision to participants in community outpatient settings. Although DSH employs Liberty Healthcare to assist it in performing its responsibilities, DSH is ultimately responsible for monitoring program operations throughout the State and for providing clinical and administrative direction and support to the program. In addition, DSH serves as a liaison by participating in regular meetings with Liberty Healthcare, clinicians, and community members to address mental health or public safety issues that arise.

The courts must approve most aspects of program participants’ involvement in the program. Specifically, after a court designates an individual as an SVP, it must approve the individual’s participation in the program, determine the county in which the individual may reside, approve the individual’s personalized terms and conditions for treatment and supervision, and approve the individual’s specific residential location.

Before 2023 state law required DSH to consult with a county agency or program on the housing search. However, starting in January 2023, state law requires DSH to convene a committee of designated local stakeholders (housing committee) to provide specific consultation and assistance to DSH in locating and securing housing. Each time a court orders an individual into the program, DSH convenes a housing committee in the county where the court has designated that the individual will reside. As Figure 2 shows, the housing committee includes representatives from DSH and Liberty Healthcare, the legal counsel for the program participant, the county counsel, the district attorney, and a representative from a local law enforcement agency.

Figure 2

Required Members of Each Housing Committee

Source: State law, DSH’s contract with Liberty Healthcare, and housing committee meeting minutes.

Figure 2 shows the required members of each housing committee. DSH and Liberty Healthcare are the State’s representative and make the decision. The legal counsel for the program participant is the advocate for the program participant. County counsel, the district attorney, and local law enforcement are the county representatives and advise DSH.

Audit Results

Individuals Who Participate in the Program Reoffend Less Often Than Those Who Do Not Participate

DSH Has Faced Significant Hurdles When Attempting to Place Program Participants Into the Community

DSH Can Improve How It Monitors Liberty Healthcare’s Administration of the Program

The Costs to Administer the Program Have Significantly Increased

Individuals Who Participate in the Program Reoffend Less Often Than Those Who Do Not Participate

Key Points

- Program participants have significantly better outcomes for public safety compared to outcomes for unconditionally released SVPs who did not participate in the program. Only two of the 56 program participants placed into the community since the program’s inception have been convicted of subsequent offenses. In comparison, 24 of the 125 unconditionally released SVPs who did not participate in the program were convicted of subsequent offenses.

- One likely reason that the program reduces reoffense rates is that a court can revoke an individual’s participation in the program, recommitting that individual back to the secure care of a state hospital for an indeterminate length of time. This process allows the courts to prevent reoffenses if a program participant’s mental health or compliance with requirements appears to be worsening.

Only 4 Percent of Program Participants Reoffended After Their Release Into the Program, but 19 Percent of Nonparticipating SVPs Reoffended

Program participants have been convicted of offenses subsequent to their conditional release into the program at a significantly lower rate than SVPs whom the courts ordered to be unconditionally released from a state hospital into the community without participation in the program (nonparticipating SVPs).

We reviewed SVP release data from January 2006 to March 2024 and criminal history data from the California Department of Justice to compare the subsequent convictions of 56 program participants with those of 125 nonparticipating SVPs.1 We categorized the subsequent felonies into four types. Table 1 shows the number of subsequent felony convictions by category as well as the total number of subsequent misdemeanors for program participants and nonparticipating SVPs.

Of the 56 program participants, only two individuals—or 4 percent—were convicted of new offenses that they committed while they were participating in the program. Both of these program participants were convicted of felonies: one for the sexual offense of possession of child pornography and one for failing to report as a sex offender. None of the other 54 program participants were convicted of any new offenses, either during their participation in the program, or—for the 21 program participants whom the courts later ordered to be unconditionally released—within 10 years of ending participation in the program.

In comparison, of the 125 nonparticipating SVPs whom the courts released unconditionally, 24—or 19 percent—were convicted of 55 new offenses that they committed within 10 years of their release. These 55 convictions included 42 felony convictions and 13 misdemeanor convictions. Further, six of these nonparticipating SVPs received felony convictions for multiple incidents, including one person who received felony convictions for four separate incidents.

DSH cited similar results from research on recidivism outcomes for program participants who were unconditionally released and those nonparticipating SVPs who were unconditionally released directly from a state hospital. This research found that after release, program participants were three times less likely to recidivate than were nonparticipating SVPs.

The Ability to Revoke Individuals’ Conditional Release to the Community Has Likely Aided the Program in Reducing Reoffense Rates

In addition to DSH providing program participants with treatment and supervision, which, among other things, is intended to prevent them from reoffending, another likely reason for why the program has reduced reoffense rates is that the courts can revoke individuals’ participation if they begin demonstrating potentially negative behaviors, as we describe in the Introduction. For instance, DSH or the district attorney can petition the court to revoke an individual’s outpatient status and recommit them to a state hospital if their mental health worsens, if they fail to comply with program requirements (noncompliance), if they engage in risky behaviors, or if they commit an offense for which they are arrested. This option does not exist for nonparticipating SVPs. Although a revocation can result from a program participant’s failure to abide by program requirements, it does not necessarily mean that the participant reoffended. Instead, it may prevent reoffenses by preemptively returning program participants to a secure hospital setting.

Of the 56 program participants who have been placed in the community since the program’s inception in 2003, the courts have revoked 18 unique individuals’ participation, returning them to a state hospital. The courts most commonly revoked program participation for noncompliance with the terms and conditions of release. However, the court documents we reviewed did not consistently identify the specific noncompliant activities that led the court to authorize these revocations.2 As the text box shows, examples of noncompliance can include a program participant not taking prescribed medications, failing to continue mental health services, or engaging in prohibited activities.

Examples of Noncompliant Activities That May Lead to Revocation of Program Participation

- Not taking prescribed medication.

- Failing to appear at or participate in therapy sessions.

- Refusing to take a polygraph.

- Failing to submit to or testing positive in drug and substance use screenings.

- Traveling outside of the designated county without prior approval.

- Violating the law.

Source: DSH operations manual.

The courts have ordered some of the 18 individuals who had their participation in the program revoked to reenter the program, generally three to 17 years after their participation was revoked.3 As of April 2024, some of these repeat program participants were awaiting new placement locations, others were in active community placements, others had been unconditionally released after being placed in the program a second or third time, and others were in a state hospital after having their outpatient status revoked again. In one example, the court ordered an individual into the program and approved housing in the community in 2017. In June 2019, the court received a petition for revocation of the individual’s program participation, but in April 2020, the court dismissed the petition and reinstated the program participant to the previous terms and conditions. However, in October 2020, the court revoked the individual’s participation in the program for violating the conditions of release. In 2022 the court subsequently ordered the individual’s re-entry into the program, and as of April 2024, this individual was still a program participant in a community.

DSH Has Faced Significant Hurdles When Attempting to Place Program Participants Into the Community

Key Points

- State law generally allows DSH 30 days to place program participants into housing within the community; however, DSH has consistently exceeded this deadline—sometimes by years. Locating rentable homes that are sufficiently close to treatment services and adequately distant from areas where participants might pose an increased safety risk to the community requires significant and lengthy research.

- Since January 2023, state law has required DSH to convene a housing committee that includes certain county representatives when identifying each prospective community placement. However, the members of the committees we interviewed stated that they did not know what assistance DSH needed. Further, certain committee members may face conflicts when identifying potential placement locations because of their other community responsibilities.

- By establishing a state-managed transitional facility, DSH could decrease the time that program participants must wait in a state hospital until a court approves a placement location in the community. Other states and other programs in California use transitional facilities as a means to allow program participants to more rapidly begin their outpatient treatment and adjustment to living in a less restrictive environment.

The State Has Taken an Average of 17 Months to Place Program Participants in the Community

State law generally requires DSH to place program participants in the community within 30 days after the court approves their participation in the program. Specifically, within 30 days after receiving notice that the court has determined that the person should be transferred to the program, unless good cause for not doing so is presented to the court, state law specifies that DSH place a program participant in the community in accordance with a treatment and supervision plan.4 Nevertheless, securing an appropriate location for a program participant historically has taken significantly longer than the time frame allowed in state law. In fact, Liberty Healthcare—working with DSH—took an average of 17 months to complete the process of securing housing for current program participants from the time when the court ordered a patient’s participation in the program to the court’s approval of the placement location. For two program participants, each placement approval took more than three years.

As of April 2024, Liberty Healthcare had yet to secure appropriate placements for 20 patients whom courts had ordered to participate in the program. These individuals had been waiting an average of 20 months for housing placements, with some waiting much longer. For example, the courts ordered one individual to participate in the program in October 2019, and this individual was still waiting for a housing placement as of April 2024, a period of about four and a half years.

The process to locate appropriate housing involves many steps, as Figure 3 outlines. After the court determines the specific county in which a program participant should reside, Liberty Healthcare obtains relevant placement information—such as the participant’s key risk factors and the prior victim profiles—to ensure that its search criteria will meet the participant’s needs and placement requirements. Liberty Healthcare then uses online home search websites to identify a potential property, and it confirms that the property owner is willing to rent the property to the State for purposes of housing a program participant.

Figure 3

The Process to Locate Appropriate Housing for Placement Involves Many Steps

Source: Liberty Healthcare’s policies and DSH’s policies.

* DSH may convene a housing committee at any time before submitting a proposed property to the court.

Figure 3 outlines the processto locate appropriate housing. This process includes various steps such as conducting a housing search, meeting with property owners, conducting an internal review process at DSH, and eventually scheduling a hearing date with the court to determine whether the proposed address is appropriate for the program participant.

Liberty Healthcare next determines whether the location meets residential restrictions by conducting a site assessment, as Figure 4 describes. This process can be complicated. For example, state law prohibits placing certain program participants within one-quarter mile of any K‑12 school. Further, an appellate court ruled that home schools fall within the definition of schools under this law, including home schools that are established after a program participant location was already determined. Thus, the establishment of a home school can necessitate relocating a program participant from existing housing to a state hospital until Liberty Healthcare can find a new location. According to Liberty Healthcare, it must conduct additional research to rule out the existence of nearby home schools. To help better ensure public safety, Liberty Healthcare also eliminates from its search results any locations near where children live or gather, such as preschools, playgrounds, churches, and locations providing daycare.

Figure 4

Liberty Healthcare Conducts a Site Assessment Before Proposing a Placement Location to DSH

Source: Liberty Healthcare site assessment form and auditor observation.

Figure 4 includes examples ofitems that Liberty Healthcare evaluates during a site assessment. These examples include items such as evaluating whether the is a reliable GPS signal at the location, what the law enforcement response times are in the area, and whether the location is near health care services.

After assessing a site, Liberty Healthcare presents the proposed placement location to key stakeholders to solicit their feedback. As Figure 3 describes, DSH performs three levels of internal review before presenting the proposed location to the relevant county’s housing committee for additional input. The court then schedules a hearing to consider the proposed placement location. State law requires that at least 30 days before the court hearing, DSH provide to local law enforcement and the district attorney or county counsel written notification of the location’s address and the date, place, and time of the court hearing. During the scheduled hearing, the court can approve, reject, or modify the proposal regarding the specific address or the conditions that will apply to the participant’s conditional release.

Liberty Healthcare’s struggles to place a program participant in Stanislaus County serve as an example of how difficult it can be to find appropriate placement locations. Public court records show that in October 2020, the Stanislaus Superior Court ordered an individual into the program; however, more than a year later, the court ordered that the housing search include additional counties because DSH had not yet secured suitable housing in Stanislaus, despite Liberty Healthcare having considered more than 6,500 housing sites as of August 2023. The court ultimately approved a placement; however, in February 2024, a district attorney filed a motion to reconsider the placement because there was a home school within 1,000 feet of the proposed placement address. The court granted the motion, and the housing search resumed and was still ongoing as of April 2024.

Similar to circumstances in the Stanislaus County placement example, Liberty Healthcare and DSH have encountered a number of challenges at different stages in the housing search that have further extended the time it took them to place a program participant. For example, Liberty Healthcare staff asserted that some nearby property owners have claimed to run home schools near the locations to essentially disqualify them from further consideration. Regarding one placement in San Diego County, a property owner submitted statements and testified that she homeschooled her children across the street from a proposed placement location. However, eight months after learning about the potential home school, the court found that the property owner did not live in that location most of the time and that her children were enrolled in-person at other public or private schools. Although the court allowed the program participant’s placement to go forward, the need to determine whether a home school existed near the placement resulted in additional delays.

Liberty Healthcare must not only identify available properties that would provide for appropriate placement, but the relevant property owners must be willing to rent their properties for the purpose of housing program participants, because DSH and Liberty Healthcare do not own program-specific housing. According to Liberty Healthcare’s community program director, the number of property owners willing to do so is few. Liberty Healthcare’s clinical director stated that even when a property owner is fully committed and Liberty Healthcare has properly vetted the property for meeting the required criteria, there have been instances when people have publicly harassed the property owner or sabotaged the property, making placement there no longer a viable option. In one example, vandals rendered a potential placement location uninhabitable by using a hose to flood the attic, damaging the house. Liberty Healthcare’s assistant community program director described other instances when property owners withdrew their willingness to rent their properties for the purpose of housing program participants because community members stopped patronizing the local businesses they also owned. In cases such as these, Liberty Healthcare must resume its housing search, thereby extending the time the program participants must remain in a state hospital.

Two Issues Have Hindered the Housing Committees’ Effectiveness in Assisting in the Search for Placement Locations

The housing committees have not yet proven to be an effective component in the process of locating appropriate housing for program participants and may, in fact, have contributed to delays in securing residences for some program participants. We identified two specific issues that may be impeding the housing committees from functioning as state law intended. First, DSH has not clearly defined and communicated to housing committee members the manner in which they can best assist it in locating housing for program participants. Second, some housing committee members indicated to us that they would prefer not to publicly participate in selecting program participants’ placement locations.

State law requires housing committees to advise and consult with DSH; however, it does not require the committees to produce any specific deliverables when they convene. Consequently, identifying the specific help the committees should provide is challenging. From January 2023—when state law began requiring housing committees—to April 2024, DSH convened 15 committee meetings in 10 counties, as the text box summarizes. Although the housing committee meetings are subject to public open meeting laws, significant portions of the meetings involve confidential patient information, and those parts of the meetings are held in a closed session. Further, housing committee meeting notices, agendas, and minutes are largely similar for each meeting and generally provide only a high-level summary of a meeting’s topics, such as the rollcall, the presentation of housing committee informational slides, the public comment period, and the closed session. Although the minutes include documentation of actions the committees took, these summaries often lack sufficient detail to determine what specifically was discussed. For example, minutes that we reviewed for one meeting documented the occurrence of a discussion of potential housing locations and surrounding issues, but it did not provide specific details of the discussion or the issues addressed.

Fifteen Housing Committee Meetings Occurred From January 2023 Through April 2024

- Contra Costa: December 2023

- El Dorado: November 2023

- Kern: August 2023

- Orange: December 2023

- Placer: August 2023, October 2023, January 2024

- Sacramento: July 2023

- San Diego: October 2023, March 2024

- Santa Cruz: July 2023, September 2023, March 2024

- Solano: October 2023

- Stanislaus: October 2023

Source: DSH website and housing committee meeting minutes.

When we interviewed committee members from Sacramento, San Diego, and Stanislaus counties, they explained that they did not always clearly understand how to participate in the meetings. None of them had received training for their roles in the housing committee, and although most of the committee members we interviewed attended the meetings, some stated that they did not know what type of input DSH wanted from them. District attorney representatives told us that DSH did not inform them of their role in providing assistance. Two county counsel representatives from San Diego County similarly told us that their role on the housing committee was unclear, and one stated that he was unsure about where DSH wanted him to direct his legal advice: to DSH, to the housing committee members, or to other parties in the housing search process. Housing committee members also stated that DSH did not provide them with all of the information that they wanted about the potential placements. For example, one member stated that Liberty Healthcare had not provided sufficient information about one program participant’s specific treatment needs because of health care confidentiality requirements.

Furthermore, even though DSH has convened the housing committee meetings as required, committee members have not always actively participated and, at times, have contributed to delays. For example, the Stanislaus County Sheriff’s Office did not participate in a recent housing committee but instead delegated its responsibilities to another member of the committee, the county counsel. This type of delegation of responsibilities does not comply with state law. Moreover, DSH noted that the addition of county counsel to the housing committee has resulted in adversarial relationships and interactions in the placement search. For example, DSH shared that in some counties, the county has not cooperated in scheduling the housing committee meetings, causing delays in the process. DSH also stated that there has not been a discernible benefit of adding the county counsel to the housing placement process.

According to DSH, the fact that county sheriffs and district attorneys are elected officials has also created problems because of the public nature of the placement process. The chief psychologist explained that before the creation of the housing committees, most sheriff departments were helpful in vetting locations. However, he asserted that the dynamic has now changed because of the public housing committee meetings. A housing committee member who represents the San Diego Sheriff’s Office confirmed that if a program participant reoffended, the sheriff would not want to be on the record as having endorsed the placement. As a result, he did not want to support the placement of a program participant into the community. In fact, both the San Diego Sheriff’s Office and the San Diego District Attorney’s Office have public notices on their websites stating that they are either not involved in or not responsible for selecting placement locations. Nevertheless, state law requires that representatives from these offices participate in housing committee meetings to assist and consult DSH in its efforts to secure potential placement locations.

DSH could take steps to improve the effectiveness of the housing committees. For example, we expected that DSH would have provided guidance to the committee members to encourage their participation and ensure their clear understanding of their roles. However, DSH believes that court orders are more efficient and effective in compelling participation in the housing committee meetings than guidance it could provide. In addition, DSH asserts that it seeks the members’ input about placement suggestions, such as by identifying county land that it could use for placements or requesting assistance with local code compliance issues. Nevertheless, had DSH clarified what assistance it desired from the members of the committees we interviewed, these members might have been able to provide more timely or more effective help.

Other States Use Transitional Housing for Similar Programs

California does not have a housing alternative that it can provide to program participants in the time from when the court orders their program participation to when DSH has secured for them an approved placement in the community. Currently, individuals whom a court has authorized to participate in the program must remain in the restrictive state hospital setting until the court approves a residence in the community. As we previously discuss, placements of program participants in approved residences currently take an average of 17 months, far longer than the 30 days following court orders of conditional release into the program that state law generally requires.

Multiple other states have programs that are similar to California’s program and that use state-owned, state-operated, or contracted transitional housing for participants who are no longer confined to state hospitals. For example, Washington, Minnesota, Kansas, and Texas each use transitional group housing to serve as an intermediate step between receiving treatment in a state hospital and receiving treatment in a community setting. Generally, such transitional facilities are less restrictive alternatives to a state hospital and provide supervision that is commensurate with the risk levels the residents may pose. Washington’s conditional release program uses secure transitional facilities with statutorily specified security measures and staffing, as well as contracted community transitional facilities, which may have 24‑hour staffing and escorts when residents travel outside of the facilities.

Texas state law explicitly requires a tiered program for supervision and treatment to provide for the transition of a committed person from a total-confinement facility to less restrictive housing and supervision and to eventual release from civil commitment. The law further requires Texas to operate or contract with a vendor to operate facilities for this program. Kansas and Minnesota operate transitional facilities for reintegration of individuals who have shown progress through treatment. Minnesota’s facility includes a level of transitional housing for patients approved by a court to live outside of a secure perimeter.

Both DSH and Liberty Healthcare told us that placing program participants in community transitional facilities could be beneficial and that a community‑located facility not within the secure perimeter of a state hospital would best facilitate individuals’ transition to the program. According to DSH’s assistant chief psychologist, moving a program participant to a transitional facility could alleviate long detentions in a state hospital after the court has ordered the individual to be conditionally released into the program. She also stated that the use of transitional facilities is consistent with research on the treatment of higher-risk sex offenders in managing their transition and could improve patient and staff morale.

California currently operates transitional and congregate housing for other categories of CONREP participants, such as individuals whom the courts have committed to DSH because they were incompetent to stand trial or were judged to be not guilty by reason of insanity. However, state law does not include provisions for creating such a facility for this program or for the admission of these program participants to the other CONREP transitional facilities. The assistant chief psychologist told us that similar facilities for the program could alleviate program participants’ long waits to be placed and incentivize program participation.

DSH Can Improve How It Monitors Liberty Healthcare’s Administration of the Program

Key Points

- Our review of the 19 current program participants’ records found that Liberty Healthcare had up-to-date annual treatment plans for 17 of the participants. The plans for the two remaining participants were signed the day after we requested them for this audit. When we assessed a selection of program participants’ records, we found that Liberty Healthcare had generally provided to program participants the treatment services we reviewed.

- Although DSH’s contract with Liberty Healthcare is not subject to the State’s standard contract oversight mechanisms, DSH regularly assesses Liberty Healthcare’s compliance with program requirements. Specifically, DSH performs scheduled reviews of Liberty Healthcare four times a year, and it conducted a more thorough program review in 2019.

- DSH does not have an effective oversight process to track and monitor Liberty Healthcare’s implementation of the recommendations that DSH makes as a result of its reviews. Consequently, DSH has allowed several known deficiencies to persist since at least 2019 without holding Liberty Healthcare accountable for implementing timely resolutions.

Liberty Healthcare Has Generally Provided Services to Program Participants as Required

In compliance with DSH’s operations manual, DSH’s contract with Liberty Healthcare requires that Liberty Healthcare assess each program participant’s needs annually and create a treatment plan that aligns with those needs. The treatment plan should consist of treatment goals and objectives that address many elements of mental health care, including diagnoses, offense-related situations and behaviors, and warning signs and risks factors for reoffending. DSH requires that a diverse group participate in meetings to develop these treatment plans, including the Liberty Healthcare community program director, a polygraph examiner, and treatment providers. The group may also include local law enforcement representatives.

Liberty Healthcare’s community program director explained that Liberty Healthcare holds a meeting within the first 90 days after a program participant is placed into the community to develop the treatment plan. It then holds monthly meetings while the participant is in a community residence to monitor the participant’s progress. The community program director implements necessary changes from the initial meeting by revising the plan annually and then reviewing the plan with the program participant. Following such revisions, the participant and a representative from Liberty Healthcare sign the plan, which indicates that they have reviewed the plan, including updated goals and planned treatment.

When we reviewed the current annual treatment plans for the 19 program participants in the program as of April 2024, we found that Liberty Healthcare had up-to-date annual treatment plans for 17 of the 19 program participants, as Table 2 shows. However, the other two plans were signed more than one month after they were first created and one day after we requested them. Further, one of the two plans Liberty Healthcare gave us was still missing the program participant’s signature. According to Liberty Healthcare, the process for creating an annual plan generally requires different reviews, which can result in staggered dates for when all parties signed the final version. However, Liberty Healthcare expects that it will be able to eliminate such delays when it begins collecting electronic signatures from all parties simultaneously. Nevertheless, to ensure that it is able to accurately monitor program participants’ progress, Liberty Healthcare must ensure that it reviews and collects signatures promptly for all treatment plans.

DSH’s contract with Liberty Healthcare requires that Liberty Healthcare must provide a specific quantity of core clinical treatment services each month that are commensurate with a program participant’s level of care. These services include individual and group treatment, substance use screening, and home visits. Appendix B outlines these services and their required frequency in more detail. When we reviewed the case files for a selection of 10 of the 19 participants in the program as of April 2024, we found that Liberty Healthcare had performed the required quantity of home visits, substance use screenings, and individual therapy sessions as Table 2 shows.

Our review also found that Liberty Healthcare performed all of the required number of sexual interest screenings or sexual arousal assessments, with the exception of one service for one program participant in 2023. According to Liberty Healthcare, that program participant did not receive either test at that time because the participant was very ill. However, Liberty Healthcare did not request a waiver of the sexual interest screening or sexual arousal assessment requirement because it intended for this program participant to receive the service. Liberty Healthcare asserts that it is currently assessing the program participant to determine whether the individual continues to meet the criteria for commitment as an SVP. Nevertheless, Liberty Healthcare has generally provided the treatment services that we tested to the program participants while placed in the community.

DSH Regularly Assesses Liberty Healthcare’s Compliance With Program Requirements

DSH’s contract with Liberty Healthcare is exempted by statute from the State’s contracting requirements.5 Consequently, Liberty Healthcare is not subject to the State’s standard contract oversight mechanisms, which include requirements for the contracting agency (DSH) to maintain records related to the contractor’s performance and to document nonperformance of contract services. However, DSH’s contract with Liberty Healthcare does permit DSH to monitor Liberty Healthcare’s compliance with requirements for treating patients. Further, the contract allows DSH to perform audits and quality assurance reviews to ensure that Liberty Healthcare is meeting the department’s standards and following its procedures. In general, we found that the terms of the contract are consistent with the legal requirements for placing, treating, and supervising program participants.

In addition to its regular interactions with Liberty Healthcare through the normal course of business, DSH has opted to use two oversight mechanisms to monitor Liberty Healthcare’s compliance with program requirements: program reviews and quarterly reviews. DSH designed the program review to allow it to evaluate whether Liberty Healthcare is providing safe, ethical, and effective clinical treatment and supervision services that benefit program participants and protect public safety. The quarterly reviews are smaller in scope than are the program reviews, but they allow DSH to routinely evaluate individual patient records and assess new or ongoing barriers to the program’s success.

The operations manual states that DSH should perform a program review of each contractor with which it contracts to operate the program. Although the operations manual requires DSH to conduct these program reviews only once for each contractor, it allows DSH to conduct additional program reviews as necessary to ensure that a contractor is operating the program in compliance with state laws and policies. As we previously discuss, Liberty Healthcare has been the program’s only contractor since its inception in 2003. According to DSH’s assistant chief psychologist, DSH has performed only one program review of Liberty Healthcare’s operations, which it completed in May 2019. As the text box shows, DSH organized this program review into two areas. DSH issued a report in December 2019 that summarized the results of its program review. We discuss the results of the program review, along with the results of the quarterly reviews, in the next section.

Some of the Factors DSH Considered During Its 2019 Program Review

Program Administration and Operations:

- Organizational structure

- Clinical staff composition

- Policies regarding clinical procedures

- Communication of policies and procedures

- Operational protocols

Clinical Services and Documentation:

- Treatment plans

- Treatment services

- Patient supervision

- Patient records

Source: DSH’s operations manual and its 2019 report to Liberty Healthcare regarding the results of the program review.

Although it has been more than five years since the 2019 program review, DSH stated that it has not scheduled its next program review because too many changes are underway. DSH’s chief psychologist explained that because the January 2023 change to state law altered the program dramatically, conducting another program review would not make sense until its operations stabilized. Further, he anticipates that the program will incorporate the recommendations resulting from this audit. Nevertheless, we note that DSH has had more than a year and a half to make adjustments to the program since the change to state law. Further, the emergence of new program requirements makes it more urgent, not less, for DSH to proactively conduct its own program review to ensure the program’s compliance with state law.

DSH also performs quarterly reviews to routinely monitor Liberty Healthcare’s compliance with program requirements. Although state law does not require DSH to conduct these types of reviews, DSH has done so since at least January 2020. During the quarterly reviews, DSH reviews various aspects of Liberty Healthcare’s administration of the program, as the text box shows. We found that DSH completed each of the eight quarterly reviews it was scheduled to perform in 2022 and 2023. Following completion of each quarterly review, DSH reported deficiencies to Liberty Healthcare in a written report that it refers to as an executive summary.

Examples of Activities in DSH’s Quarterly Reviews of Liberty Healthcare

- DSH reviews the policies and procedures that Liberty Healthcare is contractually required to develop to ensure that they align with DSH’s operations manual. For example, in the December 2023 quarterly review, DSH reviewed Liberty Healthcare’s policies related to transporting individuals while participating in the program and policies related to unconditionally releasing program participants.

- DSH reviews patient medical records—including terms and conditions, treatment plans, treatment session notes, and billing records—to compare the number and types of services that program participants received to the number of services required by their designated service level and treatment plan.

- DSH assesses the effectiveness of Liberty Healthcare’s GPS monitoring and emergency on-call service.

- DSH assesses the effectiveness of Liberty Healthcare’s handling of program participants’ revocations from the program back to civil commitment in the state hospital.

- DSH assesses ongoing barriers that affect Liberty Healthcare’s housing search and timely placement of program participants into the community.

- DSH follows up on the status of outstanding recommendations it made during its previous quarterly reviews and the 2019 program review.

Source: Interviews with DSH’s assistant chief psychologist, DSH’s executive summaries to Liberty Healthcare, and DSH’s internal notes for the quarterly reviews it conducted in 2022 and 2023.

DSH Has Not Held Liberty Healthcare Accountable for Resolving Outstanding Deficiencies

In the report on the 2019 program review and in the executive summaries of the quarterly reviews, DSH identified various deficiencies in Liberty Healthcare’s administration of the program. Additionally, DSH found across multiple quarterly reviews some of the same issues that Liberty Healthcare had yet to resolve—including some problems that DSH had identified in its 2019 program review. For example, in both the program review and in the subsequent quarterly reviews, DSH found that some of Liberty Healthcare’s policies and procedures were outdated and incomplete. DSH’s specific findings included that Liberty Healthcare had not established policies and procedures for how to safely manage program participants during an emergency. Further, it found that Liberty Healthcare had not updated its contraband policy since 2011. It also found that Liberty Healthcare had not consistently and adequately trained its staff about how to testify in court.

In another example, DSH’s 2019 program review and all of the executive summaries we reviewed stated that providers and supervisory staff did not regularly have timely access to relevant records for each patient. Liberty Healthcare stores hard-copy records at its main office in San Diego and uses an electronic document repository system. However, DSH concluded that the electronic system was not functioning in a manner that allowed clinician staff, supervision staff, and subcontractors working off‑site to access all necessary documents—such as patient records and court reports—to inform treatment decisions and mitigate risks to public safety. Therefore, staff may not have been able to determine whether a change in treatment approach was needed. In fact, DSH noted examples in its program review in which treatment providers were not privy to facts of specific incidents and made clinical opinions based upon limited information, such as information self-reported by the program participant. DSH explained the possibility that the treatment providers’ clinical opinions might have differed if they were aware of specific relevant information that may have existed in the participants’ records.

Further compounding the issue, DSH noted in its quarterly reviews that Liberty Healthcare did not maintain an index identifying the location and nature of all documents contained in each program participant’s record. The assistant chief psychologist stated that as a result, DSH was unable to discern whether a particular document it expected to see simply did not exist or was merely inaccessible to its staff. She further explained that Liberty Healthcare initially responded to these concerns by implementing a new system that it asserted would address the underlying problems. However, that system did not successfully resolve DSH’s concerns, and the issue remains outstanding. Liberty Healthcare is currently in the process of implementing a different system to address this issue.

DSH’s contract with Liberty Healthcare requires DSH to establish a deadline for Liberty Healthcare to correct any deficiencies that DSH identifies in its audits and reviews, noting that failure by Liberty Healthcare to correct deficiencies in a timely manner would constitute a reason for termination of the contract. However, DSH does not hold Liberty Healthcare accountable for formally tracking its implementation efforts. For example, DSH initially asked Liberty Healthcare to submit a written corrective action plan within 45 days of DSH submitting the report of the program review to Liberty Healthcare in December 2019. However, Liberty Healthcare requested, and DSH continually granted, six-month extensions until DSH rejected any further extensions in October 2021. Liberty Healthcare did not submit its response to DSH until January 2022, about two years after the original deadline. DSH does not currently require Liberty Healthcare to submit a written response to the quarterly review executive summaries.

With the program deficiencies identified in the program review and the new and repeat issues DSH has identified in quarterly reviews, we expected that DSH would have implemented a structured method for monitoring Liberty Healthcare’s progress toward remediating recommendations resulting from the program and quarterly reviews. For example, we expected that to assist Liberty Healthcare with prioritizing its remediation efforts, DSH would have assigned a criticality rating to each recommendation reflecting its significance. Further, to help it assess the adequacy of Liberty Healthcare’s corrective actions, we expected that DSH would require Liberty Healthcare to develop a tracking mechanism—such as a spreadsheet or dashboard—that would detail the tasks that Liberty Healthcare needs to accomplish to resolve each recommendation and those tasks’ expected completion dates. Finally, we expected that DSH would require Liberty Healthcare to submit regularly scheduled status updates until it fully addressed all recommendations.

However, DSH has not employed such oversight methods. Rather, the assistant chief psychologist described DSH’s manual process of maintaining a binder with a hard-copy print out of the 2019 program review report that its staff use during the quarterly reviews to jot down hand-written notes to document Liberty Healthcare’s progress toward remediating each deficiency. Despite not having an adequate method to track Liberty Healthcare’s remediation efforts, she asserted that as of July 2024, Liberty Healthcare had sufficiently addressed 29 of the 39 program review recommendations and had made progress on the remaining recommendations.

DSH also relies on the executive summaries from its quarterly reviews to track Liberty Healthcare’s progress toward remediating deficiencies; however, DSH’s continued identification of the same deficiencies across several reviews indicates that this oversight mechanism has been ineffective at ensuring timely resolution of those deficiencies. For example, nearly half of the recommendations DSH made as a result of its May 2019 program review pertained to Liberty Healthcare’s policies and procedures, and the eight quarterly reviews we evaluated consistently repeated these concerns. Nonetheless, as of July 2024, the assistant chief psychologist confirmed that a finalized policies and procedures manual remained outstanding. Those remaining deficiencies mean that Liberty Healthcare’s staff may not be administering the program consistently.

Although the assistant chief psychologist acknowledged that DSH’s manual process of tracking Liberty Healthcare’s remediation efforts is not ideal, she stated that DSH would require additional administrative support to implement a more structured approach. However, if DSH directed Liberty Healthcare to provide a detailed corrective action plan, corresponding timeline, and regular progress updates, DSH could minimize the amount of time its own staff spend trying to determine the status of the recommendations. Because DSH lacks an effective oversight process for monitoring Liberty Healthcare’s remediation of known deficiencies, DSH cannot ensure that Liberty Healthcare is prioritizing and addressing these deficiencies.

The Costs to Administer the Program Have Significantly Increased

Key Points

- The annual costs to the State of operating the program increased nearly 75 percent from fiscal years 2018–19 through 2022–23—they grew from $6.6 million to $11.5 million. Most of the increased program costs were for contracted services that Liberty Healthcare performed. DSH reported that its own costs for administering the program and overseeing its contractors had also increased.

- Over this same period, DSH’s annual payments to Liberty Healthcare rose from $5.3 million to $9.4 million, an increase of 77 percent. The higher costs resulted from several factors, including an increase in the number of program participants, a rise in the cost of housing, and the incorporation of some private security services into Liberty Healthcare’s contract in fiscal year 2022–23. Liberty Healthcare also increased the rate it charges for its services.

- DSH has not identified alternatives to its use of Liberty Healthcare to perform substantially all program services. Although DSH has solicited input from other potential contractors by issuing requests for information (RFI) at least four times, it reported that it did not receive any bids from vendors other than Liberty Healthcare.

The Majority of the Program’s Costs Are for Contracted Services

From fiscal years 2018–19 through 2022–23, DSH’s annual program expenditures increased from $6.6 million to $11.5 million. The majority of these expenditures have been for services—such as treatment and supervision of program participants—that Liberty Healthcare has provided. DSH also paid two other vendors to provide security services. However, costs for these additional vendors have totaled only about $1.2 million over the last 10 years.

DSH stated that its own personnel costs have risen significantly in recent years, in large part because of the increased workload involved in the housing approval process. As we previously discuss, since January 2023, state law has required DSH to convene a housing committee to advise DSH on placement options for each program participant. Both DSH and Liberty Healthcare report spending more time and effort to coordinate and hold these meetings, which are subject to open meeting laws. DSH does not specifically track costs associated with the meetings but estimated that its personnel costs increased from about $300,000 in 2022—the year before changes went into effect—to nearly $900,000 in 2023. Following requests from DSH for additional resources that specifically cited the housing committee meetings and other related program workload increases, the Legislature increased the number of staff dedicated to the program from five in 2022 to nine in 2023.

Finally, to determine whether counties were incurring significant costs related to their participation in the program’s placement process, we asked a selection of housing committee members about the costs of their participation. However, the housing committee members we interviewed generally did not track what it costs to perform activities that include participating in committee meetings and providing assistance and consultation to locate appropriate housing for program participants.

Liberty Healthcare Expenditures Have Increased

From fiscal years 2003–04 through 2023–24, DSH contracted for a total of nearly $93 million in services from Liberty Healthcare. As Figure 5 shows, the associated annual contract maximum amounts and expenditures have steadily increased. From fiscal years 2018–19 through 2022–23, DSH’s annual payments to Liberty Healthcare for program services increased by 77 percent, growing from $5.3 million to $9.4 million.

Figure 5

DSH’s Contract and Payment Amounts to Liberty Healthcare Have Increased Significantly Over the Last 20 Years

Source: DSH’s contract and accounting records.

Note: DSH did not maintain payment data for Liberty Healthcare before fiscal year 2008–09.

Figure 5 is a bar chartshowing the annual Liberty Healthcare contract maximum amount and the payment amounts to Liberty Healthcare from state fiscal year 2003-04 through 2022-23. The bar chart shows that both amounts increased over time. Note that DSH did not maintain payment data for Liberty Healthcare before fiscal year 2008-09. The contract maximum amounts range from less than $1 million in 2003-04 to $11 million in 2022-23. The payment amounts range from more than $3 million in fiscal year 2008-09 to more than $9 million in fiscal year 2022-23.

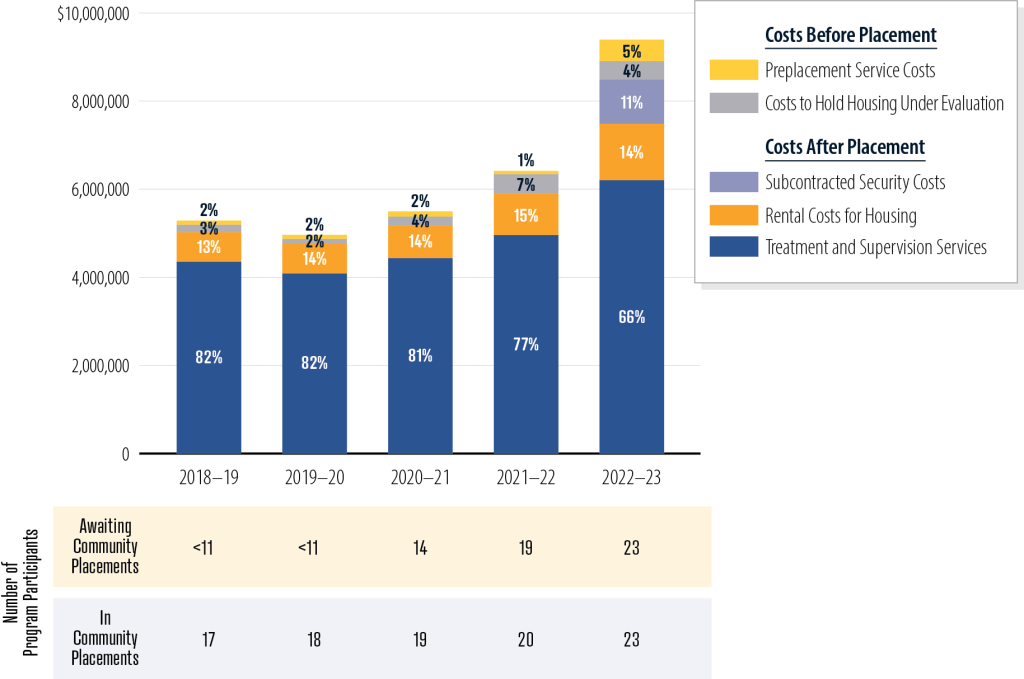

DSH pays Liberty Healthcare for five categories of services. In terms of payments, the largest of these categories is treatment and supervision services, as Figure 6 shows. Payments for treatment and supervision services accounted for at least 66 percent of DSH’s total payments to Liberty Healthcare each year from fiscal years 2018–19 through 2022–23.

Figure 6

The Majority of DSH’s Payments to Liberty Healthcare Are for Treatment and Supervision Services

Source: Analysis of DSH accounting records and court records.

Note: Because of privacy requirements related to health information for a small number of program participants, we do not disclose the exact number of program participants awaiting community placement in years before fiscal year 2020–21. In addition, percentages do not always total to 100 because of rounding.

Figure 6 is a stacked barchart showing the proportion of DSH’s payments to Liberty Healthcare to each of the five categories of service from state fiscal year 2018-19 through 2022-23. The five categories are broken down into two groups: the costs before placement and the costs after placement. The costs before placement include preplacement service costs and the costs to hold housing under evaluation. The costs after placement include treatment and supervision services, rental costs for housing, and subcontracted security costs. The figure also depicts the number of program participants awaiting community placements and the number in community placements for each fiscal year between 2018-19 and 2022-23. However, because of privacy requirements related to health information for a small number of program participants, we do not disclose the exact number of program participants awaiting community placement in years before fiscal year 2020-21.

In addition to increased costs resulting from inflation, one reason that costs for treatment and supervision services have increased is that the number of program participants in community placements—one of the main drivers behind the cost of treatment and supervision—rose by 35 percent during the past five years, from 17 individuals in fiscal year 2018–19 to 23 individuals in fiscal year 2022–23. During that same period, the negotiated contract reimbursement rate for treatment and supervision services increased by about 15 percent, from $21,000 to more than $24,000 per program participant per month. However, total costs for these services could vary depending on how many participants were in the program at a given time.

Rising housing costs—which are subject to market forces that are not under DSH’s control—have also affected the cost of the contract with Liberty Healthcare. For example, Liberty Healthcare pays the rents for proposed placement locations while the courts consider the viability of those locations. While these costs totaled $164,000 in fiscal year 2018–19, they rose to $416,000 by fiscal year 2022–23. As Figure 6 shows, the number of program participants awaiting housing also significantly increased. During this same period, the overall cost of rent and related housing costs for active program participants increased from $660,000 to nearly $1.3 million, or 97 percent. As a result, the average annual housing cost per program participant increased by 43 percent, from nearly $39,000 to about $55,000 during these five fiscal years.

The costs for Liberty Healthcare to conduct the housing search and perform other preplacement services for program participants have also increased. This increase has resulted from a number of factors. From when a participant becomes eligible for the program until that participant is placed in housing, DSH pays Liberty Healthcare a per-person monthly rate for performing services that include conducting the housing search, submitting documents to the courts, and participating in housing committee meetings. Thus, as the number of program participants awaiting placement increased from fiscal year 2018–19 through fiscal year 2022–23, the total amount DSH paid Liberty Healthcare in preplacement costs per month also rose. However, DSH does not maintain data in a way that would allow us to analyze the total costs of preplacement activities for each participant.

Changes to DSH’s contract with Liberty Healthcare have also contributed to cost increases related to preplacement services. Before July 2022, DSH reimbursed Liberty Healthcare only for the specific days during the preplacement period in which Liberty Healthcare worked on each participant’s housing search. Beginning in July 2022, DSH and Liberty Healthcare negotiated a fixed monthly preplacement cost of about $2,800 per program participant awaiting placement in the community, which was about 27 percent higher than the maximum monthly amount of about $2,200 DSH might have paid in fiscal year 2018–19. The increase in preplacement costs was particularly significant from fiscal years 2021–22 to 2022–23, when the contract change took effect: in fiscal year 2021–22, DSH paid Liberty Healthcare $72,000 in preplacement costs, but this amount grew to $485,000 in fiscal year 2022–23.

In addition, beginning in that fiscal year, DSH changed from contracting directly for security services to including those services as part of the Liberty Healthcare contract. Liberty Healthcare now subcontracts for security services, and DSH authorized it to charge a 10 percent administrative fee for managing the security firm. DSH stated that it made this change because Liberty Healthcare directly arranges for and provides oversight of the security contractor’s services, and DSH wanted to avoid additional communication steps and possible delays. Timely coordination of security matters may be important: for example, if a program participant placed in the community receives violent threats, additional security may be necessary to protect the participant. In fiscal year 2021–22, DSH paid its security contractor $500,000 for security for a total of four participants, including more than $350,000 for one program participant’s security, and in fiscal year 2022–23, DSH paid Liberty Healthcare nearly $1 million for security services.

DSH Has Not Had Success in Soliciting Bids for Administering the Program From Any Vendor Other Than Liberty Healthcare

Although state law does not specifically require DSH to obtain bids from multiple vendors to administer the program, DSH has attempted over the years to find potential contractors other than Liberty Healthcare. Since 2003 it has issued at least four RFIs to survey the marketplace, learn what services may be available from vendors, and determine the approximate costs of those services.6 In 2015 Liberty Healthcare responded to an RFI by submitting a proposal to perform services for the program. DSH issued two RFIs in 2022, and it issued another one in 2023. According to DSH, Liberty Healthcare’s proposals were the only responses DSH received to these RFIs. DSH’s chief psychologist stated that DSH has been unsuccessful in obtaining bids from any other potential contractors because the recipients of its RFIs felt that the population of SVPs poses too much risk of liability. DSH’s deputy director over CONREP programs similarly informed us that DSH has asked its contractors currently working on other programs if they have interest in working on this program, but it has not received any positive responses.