2023-129 Tropical Forest-Risk Commodities

The State Could Better Ensure That It Does Not Contribute to Tropical Deforestation

Published: August 27, 2024Report Number: 2023-129

August 27, 2024

2023-129

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee), my office conducted an audit of tropical forest-risk commodities (forest-risk commodities). Forest-risk commodities, such as beef, soy, and palm oil, are raw materials whose production in the tropics may be associated with deforestation; however, the production of these commodities does not always result in tropical deforestation. In general, we determined that the State could take some steps to better ensure that it does not contribute to tropical deforestation, but it is challenging to determine the extent of the State’s contribution.

Using available data, we determined that the State procured more than $82 million in forest‑risk commodities in 2023. However, because of the complexity of supply chains and the lack of data available for determining whether a product contains forest-risk commodities, that number could be much higher or lower. Further, the State does not have supply chain information to determine whether its procurements actually contributed to tropical deforestation. We found that the State could expand its policies to reduce the risk that it is inadvertently contributing to tropical deforestation.

Although the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act (Transparency Act) does not relate to tropical deforestation, the Audit Committee directed us to assess the State’s implementation and enforcement of the Act. We found that the State could expand the Transparency Act to incorporate other policy priorities—such as tropical deforestation—but the State would first need to address weaknesses in the Act. For example, the Franchise Tax Board (FTB) must rely on limited information from tax returns when creating a list of companies subject to the Transparency Act each year, and those lists are likely inaccurate and incomplete. In reviewing FTB’s most recent list, we found that only 10 percent of the companies we selected were in compliance with the Act. Finally, the Office of the Attorney General is responsible for enforcing the terms of the Act, including seeking injunctions against businesses that do not comply, but it has not actively determined compliance with the Transparency Act since 2016.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

| CARB | California Air Resources Board |

| CCPA | California Consumer Privacy Act |

| DGS | Department of General Services |

| EPP | Environmentally Preferable Purchasing |

| FAMS | Fleet Asset Management System |

| FSC | Forest Stewardship Council |

| FTB | Franchise Tax Board |

| LCFS | Low Carbon Fuel Standard |

| LPA | leveraged procurement agreement |

| OFAM | Office of Fleet and Asset Management |

| SAM | State Administrative Manual |

| SCM | State Contracting Manual |

| USEIA | U.S. Energy Information Administration |

Summary

California does not have specific policy goals directly related to reducing the State’s contribution to tropical deforestation. However, the State actively seeks to address climate change. Studies show that tropical deforestation accounts for an estimated 20 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, rivaling the emissions for the entire world’s transportation sector. Because of agricultural expansion, certain commodities, such as beef, soy, and palm oil, carry a significant risk of contributing to tropical deforestation. Tropical forest-risk commodities (forest-risk commodities) are raw materials whose production in the tropics may be associated with deforestation. However, the production of these commodities does not always result in tropical deforestation. Nevertheless, when governments purchase goods and services containing these commodities, they risk contributing to climate change.

The State May Be Inadvertently Contributing to Tropical Deforestation

Determining whether the production of a specific good or service contributed to tropical deforestation can be challenging. However, in some cases, it is possible to identify procurements that likely contain forest-risk commodities. Although the State does not actively track all of the forest-risk commodities it procures, the available data indicate that state agencies purchased more than $82 million in such goods and services in 2023. That same year, the State also procured about $18 million of biofuels—which can be produced with certain forest‑risk commodities—to support its fleet of vehicles and motorized equipment.

The State Could Expand an Existing Program and Policies to Combat Tropical Deforestation

The State has not established any policy goals directly related to tropical deforestation. However, if the Legislature determines that addressing this issue is a priority, the State could expand an existing program and policies to help limit its purchases of forest‑risk commodities. Specifically, the Department of General Services (DGS) has established an Environmentally Preferable Purchasing (EPP) program that provides state agencies with information on products and services that third parties have certified as having a reduced impact on the environment. Although the EPP program does not currently include certifications related to tropical deforestation, the Legislature could direct DGS to broaden the program through implementing goals and additional third-party certifications to address this issue.

Significant Weaknesses Hamper the State’s Implementation and Enforcement of the Transparency Act

Expanding the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act (Transparency Act) could also help to address tropical deforestation, but the State must first take action to ensure that it is effectively implementing the Act. Since taking effect in January 2012, the Transparency Act has required certain businesses to publicly disclose on their websites their practices and policies specific to slavery and human trafficking. However, the State has not established an effective process for identifying businesses that must comply with the law, nor has it consistently taken steps to ensure that those businesses disclose the required information. Until the State takes these steps, expanding the Transparency Act to address tropical deforestation will offer limited benefits.

Agency Perspective

This audit report does not contain recommendations specific to DGS, the Franchise Tax Board, or the Office of the Attorney General, and as a result, we did not expect responses from these entities. However, the Office of the Attorney General provided a response to our audit report. The agency agreed with our recommendations to improve the State’s implementation and enforcement of the Transparency Act.

Introduction

Background

California is actively seeking to address its contribution to climate change. In 2022, for example, the State developed a policy to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions so that by 2045, the State’s emissions levels will be 85 percent lower than its 1990 levels. Globally, studies show that deforestation is directly linked to climate change. Tropical deforestation alone accounts for an estimated 20 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, rivaling the emissions of the entire world’s transportation sector.

Because of agricultural expansion, certain commodities carry a significant risk of contributing to tropical deforestation. As the text box shows, the Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee) directed us to review 10 commodities whose production in the tropics may be associated with deforestation (forest-risk commodities). We reviewed data from global research nonprofits, such as the World Resources Institute and the Global Change Data Lab, and found these commodities to be reasonably associated with tropical deforestation. In fact, the production of beef, soy, and palm oil are responsible for 60 percent of tropical deforestation. However, because of the complexity of supply chains and the fact that these commodities do not always come from tropical forest areas (beef, for example), the State’s procurement of forest-risk commodities and products containing these commodities carries an embedded risk of contributing to tropical deforestation.

Tropical Forest-Risk Commodities

For the purposes of this audit, we define forest-risk commodities as raw materials whose production in the tropics may be associated with deforestation; however, the production of these commodities does not always result in tropical deforestation.

The Audit Committee directed us to review the following 10 forest-risk commodities:

- Beef

- Cocoa

- Coffee

- Leather

- Palm oil

- Paper

- Rubber

- Soy

- Wood

- Wood pulp

Source: Audit request, peer-reviewed research, and auditor analysis of external sources.

Additionally, the World Resources Institute determined that biofuels—renewable biological alternatives to fossil fuels, which the State uses to assist in meeting environmental goals—have also been linked to tropical deforestation since they can be produced with certain forest-risk commodities. Biofuels encompass a broad range of fuels, such as biodiesel, renewable diesel, and other fuels derived from biological materials. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (USEIA), biofuels in the U.S. are produced from vegetable oils—primarily soybean oil—along with recycled fats, cooking oils, and grease.1 Soybean oil is a forest-risk commodity.

State Procurement and Environmental Goals

The Department of General Services (DGS) is generally responsible for state policies and practices related to most of the State’s procurements. It publishes the State Contracting Manual (SCM), which provides policies, procedures, and guidelines to promote sound business decisions and practices in procuring goods and services for the State. Further, it manages the State Contract and Procurement Registration System (procurement system) to track the State’s procurement of various goods and services. DGS can consequently provide some information on the nature of the goods and services the State purchases, including whether they are from certified small businesses or disabled veteran-owned businesses and whether they meet certain state environmental purchasing standards.

In 2003 the State established the Environmentally Preferable Purchasing (EPP) program. This program promotes state agencies’ procurement of goods and services that have a lower impact on human health and the environment than would competing goods or services. For a good or service to be considered an EPP purchase, it must be environmentally preferable in such factors as durability, water efficiency, and postconsumer recycled content. The law establishing the EPP program made DGS responsible—in consultation with the California Environmental Protection Agency, among others—for providing state agencies with information and assistance regarding certified EPP purchases.

The law did not establish specific purchasing targets for the program. In 2012, however, the Governor ordered that state agencies must purchase or use environmentally preferable products whenever certain criteria are met. DGS publishes a Buying Green Guide to assist state agencies with making purchasing decisions that meet the general intent of the program. For example, the guide recommends that purchasers look for office paper products with postconsumer recycled content of at least 30 percent.

The California Transparency in Supply Chains Act

The California Transparency in Supply Chains Act (Transparency Act) is another way California is seeking to use supply chains to address a state policy goal, although the Act addresses slavery and human trafficking rather than tropical deforestation. When the Legislature created the Transparency Act, it declared that consumers and businesses are inadvertently promoting slavery and human trafficking—crimes under state, federal, and international law—through the purchase of products that have been tainted in the supply chain. The legislative findings and declarations contained in the Transparency Act explain that without publicly available disclosures, consumers are at a disadvantage in being able to distinguish companies on the merits of the companies’ efforts to supply products that are free from the use of slavery and human trafficking.

Since its implementation in 2012, the Transparency Act has required retail sellers and manufacturers that have annual worldwide gross receipts of more than $100 million and that do business in California to publicly disclose on their websites their practices and policies related to slavery and human trafficking, as the text box describes. The Transparency Act requires the Franchise Tax Board (FTB) to generate an annual list of businesses that are subject to the Act’s provisions. The Office of the Attorney General (Attorney General’s Office) is responsible for enforcing the terms of the Act, including seeking injunctions against businesses that do not comply.

Transparency Act Requirements

A company’s disclosure must, at a minimum, state to what extent, if any, the company does each of the following:

- Engages in verification of product supply chains to evaluate and address risks of human trafficking and slavery. The disclosure must specify if the verification was not conducted by a third party.

- Conducts audits of suppliers to evaluate their compliance with company standards for trafficking and slavery in supply chains. The disclosure must specify if the verification was not an independent, unannounced audit.

- Requires direct suppliers to certify that materials incorporated into a product comply with the laws regarding slavery and human trafficking of the country or countries in which they are doing business.

- Maintains internal accountability standards and procedures for employees or contractors that fail to meet company standards regarding slavery and trafficking.

- Provides company employees and management who have direct responsibility for supply chain management with training on human trafficking and slavery, particularly with respect to mitigating risks within the supply chains of products.

Source: State law.

This Audit

Our review of state law revealed that California did not have statutory goals directly related to reducing the State’s contribution to tropical deforestation. Accordingly, we did not have specific criteria against which to assess its efforts in this area. Instead, in alignment with the audit request, we determined whether the State has the data necessary to report on the extent to which its procurement choices, including its procurement of biofuels, may contribute to tropical deforestation. We further reviewed policies and practices that could help the State reduce the risk that its procurements may be contributing to tropical deforestation. Finally, although the Transparency Act does not relate to tropical deforestation, the Audit Committee directed us to assess the State’s implementation and enforcement of the Act.

Issues

The State May Be Inadvertently Contributing to Tropical Deforestation

The State Could Expand an Existing Program and Policies to Combat Tropical Deforestation

Significant Weaknesses Hamper the State’s Implementation and Enforcement of the Transparency Act

The State May Be Inadvertently Contributing to Tropical Deforestation

Key Points

- Using available data, we determined that in 2023, the State procured more than $82 million in forest-risk commodities: raw materials whose production in the tropics may be associated with deforestation.2 However, because of the complexity of supply chains, it can be challenging to determine whether the production of any single commodity contributed to tropical deforestation, and the State does not have supply chain information to determine whether its procurements actually contributed to tropical deforestation.

- Biofuel producers can use forest-risk commodities like soy and palm oil in their production of biofuels. Thus, the State’s purchase of such fuels could inadvertently contribute to tropical deforestation. Using department‑reported data and contract usage reports, we found that in 2023, the State procured about $18 million in biofuels—or 4.1 million gallons—for its fleet of motorized equipment.

The State Procured More Than $82 Million in Forest-Risk Commodities in 2023

Determining the amount of forest-risk commodities the State procures is a complicated task. The State does not have any requirement to track all forest-risk commodities in its procurement process, and DGS’s procurement system does not specifically identify this information. Moreover, because of the complexity associated with supply chains, determining whether a specific good was produced using commodities that contributed to tropical deforestation is difficult. The supply chains related to forest-risk commodities can be intricate, often involving multiple intermediaries, such as farmers, traders, and manufacturers. The commodities themselves may serve as major components or significant ingredients in various other goods, further complicating matters. For example, palm oil is a common ingredient in many processed goods, such as lipstick and peanut butter. Likewise, tires made from rubber can be found on many wheeled products, such as office chairs, moving carts, gardening equipment, and automobiles.

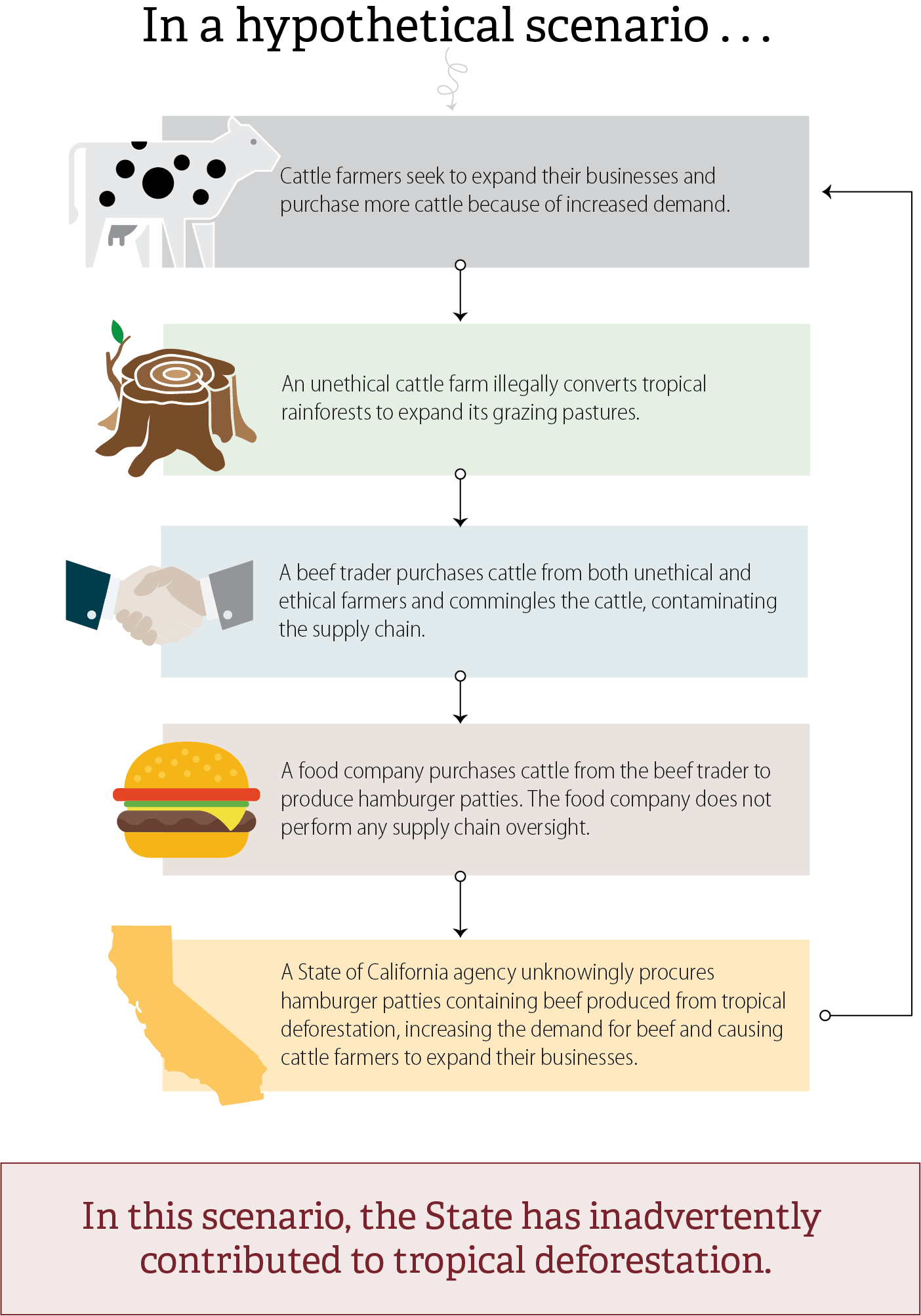

Further, some suppliers may deliberately attempt to obscure the sources of commodities. For example, a Brazilian supplier of cattle that have been raised and fed on land where illegal tropical deforestation occurred may sell the cattle to a legal supplier that does not engage in tropical deforestation. Because meat packers further down the supply chain trust the legal supplier, the cattle are effectively laundered, as Figure 1 demonstrates.

Figure 1

Complexities in the Supply Chain Could Cause the State to Inadvertently Contribute to Deforestation

Source: Peer-reviewed research articles.

In a hypothetical scenario . . . Cattle farmers seek to expand their businesses and purchase more cattle because of increased demand. An unethical cattle farm illegally converts tropical rainforests to expand its grazing pastures. A beef trader purchases cattle from both unethical and ethical farmers and commingles the cattle, contaminating the supply chain. A food company purchases cattle from the beef trader to produce hamburger patties. The food company does not perform any supply chain oversight. A State of California agency unknowingly procures hamburger patties containing beef produced from tropical deforestation, increasing the demand for beef and causing cattle farmers to expand their businesses. In this scenario, the State has inadvertently contributed to tropical deforestation.

Even when supply chain information exists, it may not be available to consumers and governments. According to DGS’s eProcurement and Business Intelligence Strategies section chief (section chief), manufacturers have not developed any uniform indicator, tracking methodology, or data point they can use to track where the materials used in their manufacturing originated. As a result, consumers such as the State cannot comprehensively identify whether the goods and services they procure contain forest-risk commodities or whether a product was actually produced through tropical deforestation. Nonetheless, the data in DGS’s procurement system contain standard descriptions of goods and services that are adequate to identify some of the State’s purchases of certain forest-risk commodities. By identifying potentially relevant transaction records, we found that in 2023, the State procured over $82 million in forest-risk commodities and products containing such commodities. This represents a fraction of the $72 billion in state procurements in 2023 that we analyzed. However, it is important to note that there are significant limitations to this total. Critically, although these procurements involved raw materials, such as leather, that may be associated with deforestation when produced in the tropics, we cannot determine with certainty that any one of the State’s specific purchases of leather directly contributed to tropical deforestation. In other words, we identified how much leather the State procured, not whether that leather’s production actually contributed to tropical deforestation. Such information is not available.

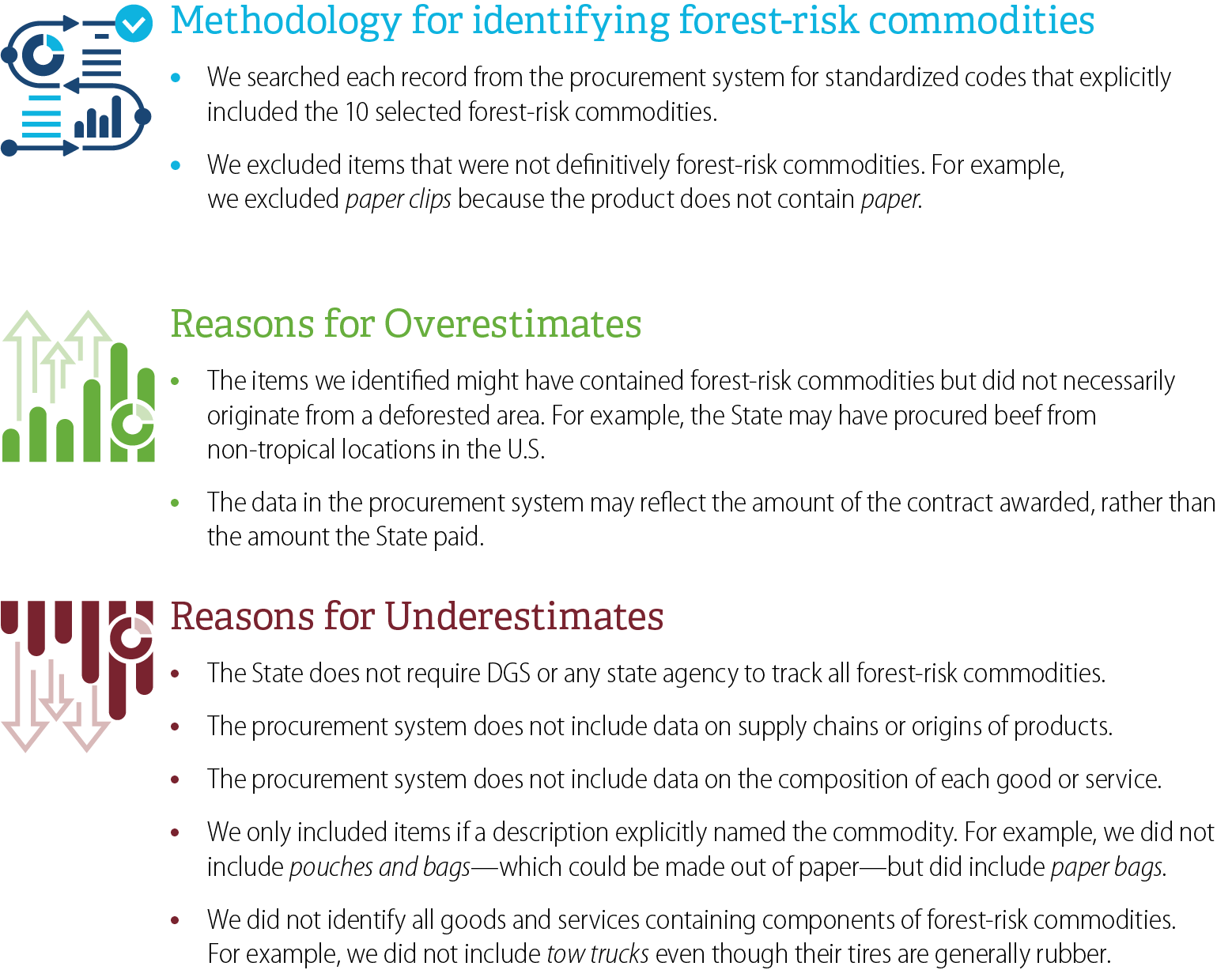

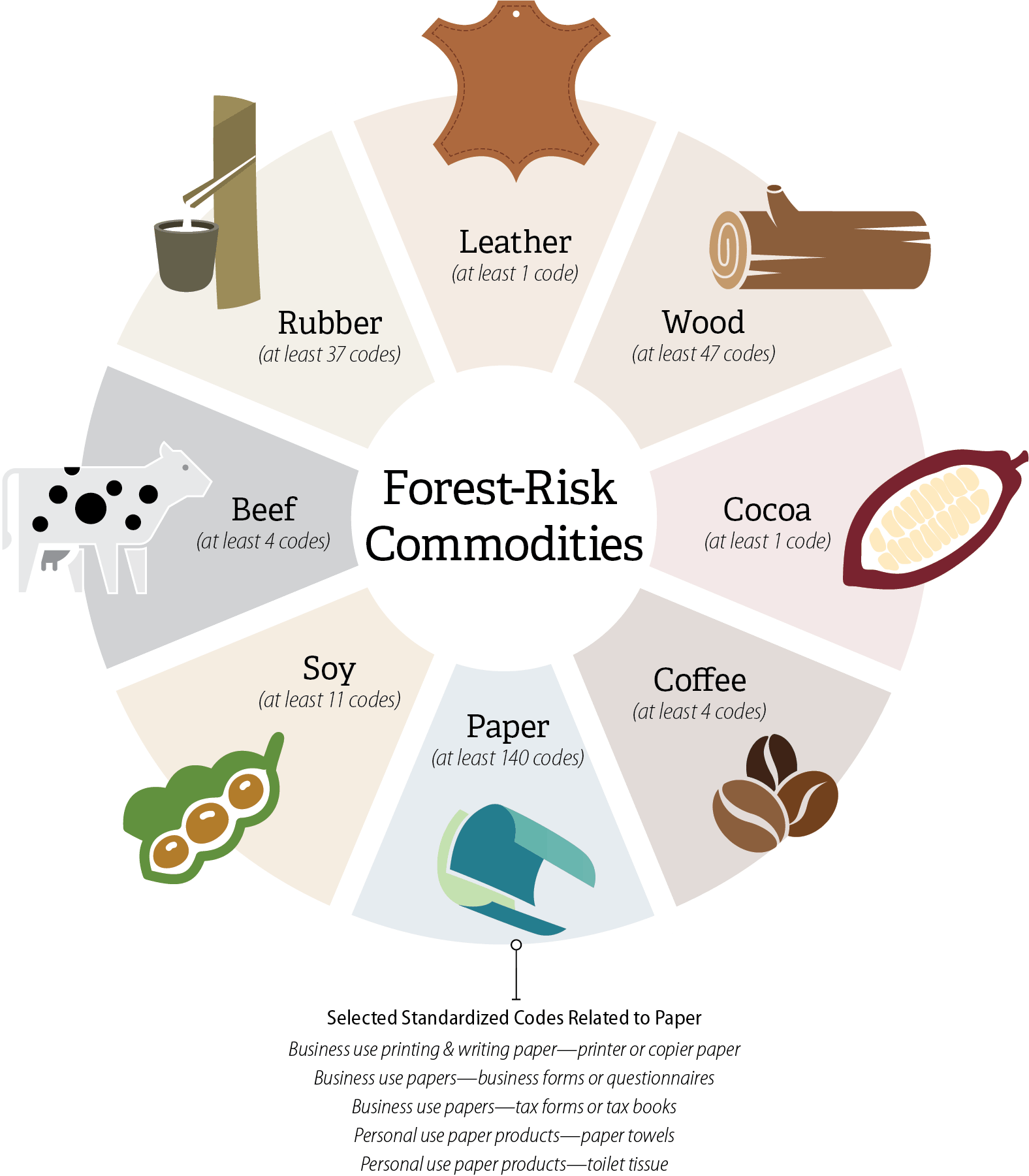

Further, as Figure 2 shows, our process for compiling the procurement data also had limitations. The data in DGS’s procurement system use about 11,000 United Nations Standard Products and Services Codes (standardized codes) that reflect the description and classification of goods and services purchased statewide. To identify forest-risk commodities, we searched the item descriptions of the standardized codes for the 10 forest-risk commodities we reviewed.3 As Figure 3 details, there can be multiple codes related to these forest-risk commodities. For example, paper has at least 140 standardized codes associated with it. As a result of our search, we selected 245 standardized codes for the purposes of our audit. However, many products may have contained commodities that we were not able to identify. For example, we did not identify any standardized codes specific to palm oil, but it may have been used in the manufacture of multiple items procured by the State, such as cleaning products and cooking oils.

Figure 2

Data Limitations Restrict Our Ability to Estimate the Amount of Forest-Risk Commodities the State Procures

Source: Auditor observation of the procurement system, procurement system data and documentation, and interviews with DGS technical staff.

To identify forest risk commodities, we searched each record from the procurement system for standardized codes that explicitly included the 10 selected forest-risk commodities. We excluded items that were not definitively forest-risk commodities. For example, we excluded paper clips because the product does not contain paper. For these reasons, the commodities we identified may be overestimated—The items we identified might have contained forest-risk commodities but did not necessarily originate from a deforested area. For example, the State may have procured beef from non-tropical locations in the U.S.. Additionally, The data in the procurement system may reflect the amount of the contract awarded, rather than the amount the State paid. For these reasons, the commodities we identified may be underestimated—The State does not require DGS or any state agency to track all forest-risk commodities. The procurement system does not include data on supply chains or origins of products. The procurement system does not include data on the composition of each good or service. We only included items if a description explicitly named the commodity. For example, we did not include pouches and bags—which could be made out of paper—but did include paper bags. We did not identify all goods and services containing components of forest-risk commodities. For example, we did not include tow trucks even though their tires are generally rubber.

Figure 3

A Single Forest-Risk Commodity May Be Linked to Dozens of Unique Standardized Codes

Source: State procurement data and standardized codes.

Note: We did not identify any standardized codes specific only to palm oil or wood pulp.

State procurement data contained at least 1 standardized code for leather, at least 47 codes for wood, at least 1 code for cocoa, at least 4 codes for coffee, at least 140 codes for paper, at least 4 codes for beef, and at least 37 codes for rubber. Selected standardized codes related to paper include “Business use printing & writing paper—printer or copier paper,” “Business use papers—business forms or questionnaires,” “Business use papers—tax forms or tax books,” “Personal use paper products—paper towels,” and “Personal use paper products—toilet tissue.”

The State procured a small percentage of this $82.6 million in goods and services from companies with an elevated exposure to tropical deforestation risk. Global Canopy, a registered United Kingdom not-for-profit organization focused on analyzing the impact of market forces on nature, annually publishes the Forest 500, a list of the 500 companies and financial institutions globally with the highest risk of being linked to tropical deforestation through involvement in or exposure to forest-risk commodity supply chains. In 2023 the State procured more than $580,000 in goods and services containing forest-risk commodities from 11 companies listed on the Forest 500.

This amount represents less than 1 percent of the total goods and services containing forest-risk commodities that the State procured in 2023 and an even smaller amount of total state purchasing in 2023. As Table 1 shows, the amount of the specific forest‑risk commodities that the State procured overall and from these companies varied, with the greatest amount spent on goods and services containing paper. Nevertheless, the State’s procurement of items from these 11 companies further illustrates the possibility that the State could be inadvertently contributing to tropical deforestation.

The State’s Purchases of Biofuels Increase the Risk That the State Is Contributing to Tropical Deforestation

The text box defines the three main types of biofuels the State procures. The State uses biofuels for its fleet of vehicles and motorized equipment, such as vehicles operated by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and by the California Department of Transportation. Information from contract usage reports and DGS’s Office of Fleet and Asset Management (OFAM) reporting indicates that in 2023, the State procured about 4.1 million gallons of biofuels to support its fleet of vehicles and motorized equipment, for a total cost of about $18 million. The State could be inadvertently contributing to deforestation if the feedstocks—the raw material used to create these biofuels—contribute to tropical deforestation.

Types of Biofuels

Biodiesel: A biodegradable, renewable fuel manufactured from biological sources like vegetable oils, animal fats, or recycled greases. Like petroleum diesel, biodiesel is used to fuel compression ignition engines. Most biodiesel in the U.S. is consumed as blends with petroleum diesel, such as in B20 (20 percent biodiesel/80 percent petroleum diesel).

Ethanol: A renewable fuel made from various plant materials collectively known as biomass. In the U.S., 94 percent of ethanol is produced from the starch in corn grain.

Renewable diesel: A biomass-based renewable fuel that can be made from nearly any biomass feedstock, including the same biological sources as biodiesel. It is chemically equivalent to petroleum diesel and can be used in existing diesel engines without modification.

Source: USEIA website, U.S. Department of Energy Alternative Fuels Data Center.

As Table 2 shows, renewable diesel accounted for about 98 percent of the State’s biofuel purchases in 2023. Moreover, according to the USEIA, California is responsible for nearly all renewable diesel consumption in the U.S., if one includes both public and private use. The State’s purchases of renewable diesel are largely the result of statewide policy. In October 2015, DGS issued an update to the State Administrative Manual (SAM)—a resource for statewide policies, procedures, and requirements—that required the use of renewable diesel in lieu of conventional diesel and biodiesel for bulk fuel purchases for diesel-powered vehicles and equipment, with some limited exemptions.4

State law and policies require state agencies to report each month their fleet of vehicles and motorized equipment’s use of fuel. State agencies make these reports using DGS’s Fleet Asset Management System (FAMS). The agencies acquire fuel using two different methods: through bulk fuel purchases they make using the State’s prenegotiated leveraged procurement agreements (LPAs) or through state fleet fuel card purchases at service stations. The LPAs allow agencies to purchase biofuels through prenegotiated contracts, streamlining the procurement process and leveraging the State’s buying power. Suppliers participating in the LPAs related to biofuels provide monthly contract usage reports to DGS that identify the amount and type of fuel the State purchased under these agreements.

The LPAs contain additional detail on applicable fuel standards—such as water and sulfur content—but neither the LPAs nor the invitation for bids that led to their award contain information regarding the origin of materials used to produce the fuel. DGS stated that the purpose of the fuel specifications is to ensure that biofuels meet quality standards, not to trace fuel back to its original raw materials or to make a determination regarding the fuel’s impact on tropical deforestation or human rights violations. Because biofuel distributors are not required to provide details about the source of the raw materials used to create these fuels, the State does not currently have a means of determining the supply chain for the biofuels it purchases.

One state agency is undertaking efforts to address deforestation in the supply chain of biofuels in California. The California Air Resources Board (CARB) administers the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS), which is designed to decrease the carbon intensity of California’s transportation fuel pool and provide renewable alternatives to reduce petroleum dependency. According to CARB, the LCFS provides economic incentives to produce cleaner fuels, including renewable diesel. As a result of the economic incentives LCFS offers, nearly all renewable diesel the U.S. produces and imports is used in California.

CARB, through amendments to the LCFS, has proposed strengthening regulations to prevent deforestation or other adverse impacts. These proposed regulations include prohibiting LCFS incentives for fuels produced from palm oil or palm oil derivatives and ensuring that crop-based and forestry-based feedstocks used to produce fuels under LCFS are harvested in a sustainable manner.5 If approved, these regulations may help to address concerns regarding the impact of the State’s use of biofuels, and specifically renewable diesel, on deforestation.

Although DGS does not monitor the supply chains of biofuel distributors, the manufacturer of much of the renewable diesel that the State procures claims to mitigate some risk associated with environmental and human rights impacts. As of April 2023, the two renewable diesel distributors with which the State had LPAs—Hunt & Sons and AAA Oil—each listed the same manufacturer for the fuel they distributed. Corporate sustainability reports from that manufacturer note that it has programs in place to address environmental and human rights impacts. The reports stated that the manufacturer works to ensure that all raw materials can be traced to the point of origin, that suppliers adhere to the vendor’s code of conduct, and that independent third-party verification bodies validate the manufacturer’s internal control process for sustainability program compliance. The manufacturer further reported that in 2022, 69 percent of the feedstock it uses for production of renewable fuels came from waste and residual sources and 31 percent from vegetable oils. In addition, the manufacturer has made public commitments to respect human rights as set out in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other similar international human rights policies.

Although commitments by this manufacturer provide some assurance of sustainability, its commitments do not address tropical deforestation specifically, nor are these commitments from manufacturers guarantees of ethical behavior. Further, in May 2023, the State began using new LPA agreements for renewable diesel, and one of those LPAs included an additional manufacturer for whom we could not locate any similar commitments regarding its efforts to address environmental and human rights impacts.

The State Could Expand an Existing Program and Policies to Combat Tropical Deforestation

Key Points

- The State has yet to establish any procurement policy goals directly related to tropical deforestation.

- The State could make initial efforts to address tropical deforestation through expanding an existing procurement program. For example, the Legislature could direct DGS to expand its listing of third-party certifications to include those specifically addressing tropical deforestation.

The State Has Not Established Any Policy Goals Directly Related to Tropical Deforestation

At present, California provides little policy guidance regarding deforestation as a determinant in state agencies’ purchasing decisions. In 2014 the State endorsed the New York Declaration on Forests, which aimed to end the loss of natural forests by 2030.6 However, this commitment is not reflected in state law or policy. In fact, state law and procurement guidance, such as the SCM, make no mention of tropical deforestation.7 In contrast, nations with economies similar in size to California’s, such as the United Kingdom, Germany, Norway, France, and the Netherlands, pledged to work on new procurement policies that limit the consumption of forest-risk commodities. France, for example, provides a formal guide as part of its National Strategy to Combat Imported Deforestation to aid government officials when making procurement decisions that may contribute to deforestation. France’s guide provides a variety of recommended proposals, such as favoring unprocessed products over processed products, which often contain palm oil. Appendix A provides additional examples of France’s proposals. Without similar specific guidance in legislation or in other state policy, state agencies lack a clear mandate to prioritize buying products that do not contribute to tropical deforestation.

The State Could Address Tropical Deforestation by Expanding an Existing Procurement Preference Program

As we previously explain, precisely tracking the forest-risk commodities the State purchases is not viable. Nonetheless, the State might be able to expand an existing procurement program to encourage state agencies to purchase goods in a way that minimizes the impact on tropical deforestation. Although it does not explicitly include tropical deforestation as a consideration, the Environmentally Preferable Purchasing (EPP) program encourages state agencies to procure goods and services that have a lesser effect on human health and the environment than would other goods and services that serve the same purpose. DGS maintains an EPP‑recommended list (EPP list) of 28 third-party certifications for various commodities that meet this standard. The EPP list notes that agencies can procure paper products with Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) labeling certifying that the paper originated in sustainably managed forests. The FSC labeling program is a voluntary, worldwide certification program that demonstrates that materials and products purchased, labelled, and sold as FSC-certified originate from well-managed forests, controlled sources, recycled materials, or a mixture thereof. The EPP list contains other certifications, similar to this one, that indirectly address the State’s exposure to tropical deforestation.

Certifications also exist that specifically focus on certain forest-risk commodities, but DGS does not currently include such certifications on the EPP list. For example, the list does not include the Rainforest Alliance Certification, which prohibits deforestation and uses third-party auditors to evaluate the supply chains of commodities such as cocoa and coffee. According to DGS, the basis for this list has historically been goods and services for which they have knowledge to analyze certifications, such as those procured through LPAs, for inclusion in the list. DGS has the authority to expand the number and types of certifications the EPP list includes. However, DGS has not updated the list since 2022. Doing so could provide additional options for state agencies seeking to meet their sustainability commitments and further mitigate the risk that the State is inadvertently contributing to tropical deforestation.

Finally, the State does not currently have goals in place for the EPP program. In 2012 the Governor required that state agencies use the EPP program when making certain purchasing decisions. However, the executive order did not include a specific goal, such as a percentage of total state purchases through the EPP program. According to DGS, neither the department nor the State generally has any other goals specific to the program. We found that about 23 percent of state purchases in 2023 were made through EPP. A specific legislative goal for the program, and additional third-party certifications that address tropical deforestation, could help minimize the risk that the State is inadvertently contributing to deforestation.

Significant Weaknesses Hamper the State’s Implementation and Enforcement of the Transparency Act

Key Points

- FTB annually generates a list of companies subject to the Transparency Act. However, because FTB must rely on limited information from tax returns when creating this list, we found that the lists are likely inaccurate and incomplete.

- From 2015 to 2016, the Attorney General’s Office took steps to enforce companies’ compliance with the Transparency Act. We reviewed FTB’s most recent list and found that only 10 percent of the companies we sampled were in compliance with the requirement that they disclose on their websites their efforts to eliminate slavery and human trafficking practices from their supply chains. The Attorney General’s Office has not actively enforced the Transparency Act since 2016.

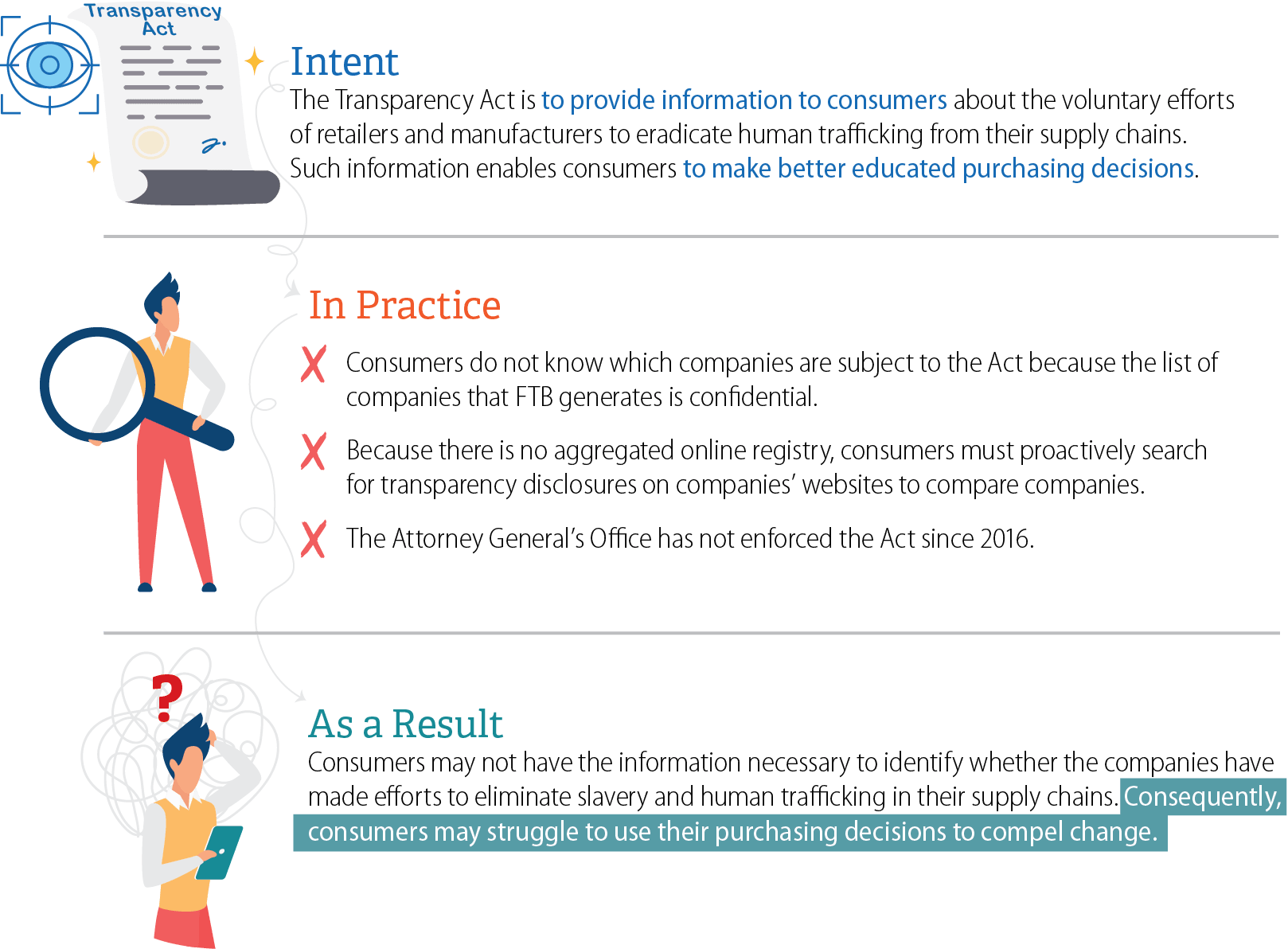

FTB’s List of Companies Subject to the Transparency Act Is Not Accurate

Although the Transparency Act does not address tropical deforestation, as we discuss in the Introduction, the Audit Committee directed us to assess the State’s implementation and enforcement of the Act. During our review, however, we found that the State could expand the Transparency Act to incorporate other policy priorities—such as tropical deforestation—but that the State would first need to address weaknesses in the Act. As we discuss in the Introduction, the Transparency Act requires retail sellers and manufacturers that have annual worldwide gross receipts of more than $100 million and that do business in California to publicly disclose on their websites, if they have one, their efforts to eradicate slavery and human trafficking from their direct supply chains. Ideally, expanding the Transparency Act to require companies to publicly disclose their efforts to combat tropical deforestation could provide additional information to consumers as they make their purchasing decisions. When we discussed such an expansion with FTB and with the Attorney General’s Office, both agencies stated that it would not significantly increase their workload. However, as Figure 4 shows, the State should first resolve weaknesses in the Act that impede its ability to achieve its intended purposes.

Figure 4

The State Has Not Ensured That the Transparency Act Fulfills Its Intended Purpose

Source: State law and staff interviews with FTB and the Attorney General’s Office.

The Transparency Act is to provide information to consumers about the voluntary efforts of retailers and manufacturers to eradicate human trafficking from their supply chains. Such information enables consumers to make better educated purchasing decisions. In practice, consumers do not know which companies are subject to the Act because the list of companies that FTB generates is confidential. Because there is no aggregated online registry, consumers must proactively search for transparency disclosures on companies’ websites to compare companies. The Attorney General’s Office has not enforced the Act since 2016. As a result, consumers may not have the information necessary to identify whether the companies have made efforts to eliminate slavery and human trafficking in their supply chains. Consequently, consumers may struggle to use their purchasing decisions to compel change.

Most importantly, the effectiveness of the Transparency Act depends on the requirement that FTB provide the Attorney General’s Office with a list of companies that are subject to the Act’s provisions. However, we found that FTB’s lists are likely inaccurate and incomplete. For example, because of complexities related to the tax code, FTB cannot ascertain with certainty that all of the companies on the list it provides to the Attorney General’s Office are actually subject to the Act. In addition, we reviewed an industry list of the top 25 U.S. retailers and manufacturers and found that 14 were not on FTB’s most recent list. The confidentiality of FTB’s list prevents us from disclosing the names of those companies. Nonetheless, more than half of these companies maintain Transparency Act disclosures on their public websites. Notwithstanding this, the Attorney General’s Office stated that to investigate companies that are not on FTB’s list would be beyond the scope of the legislation as currently written.

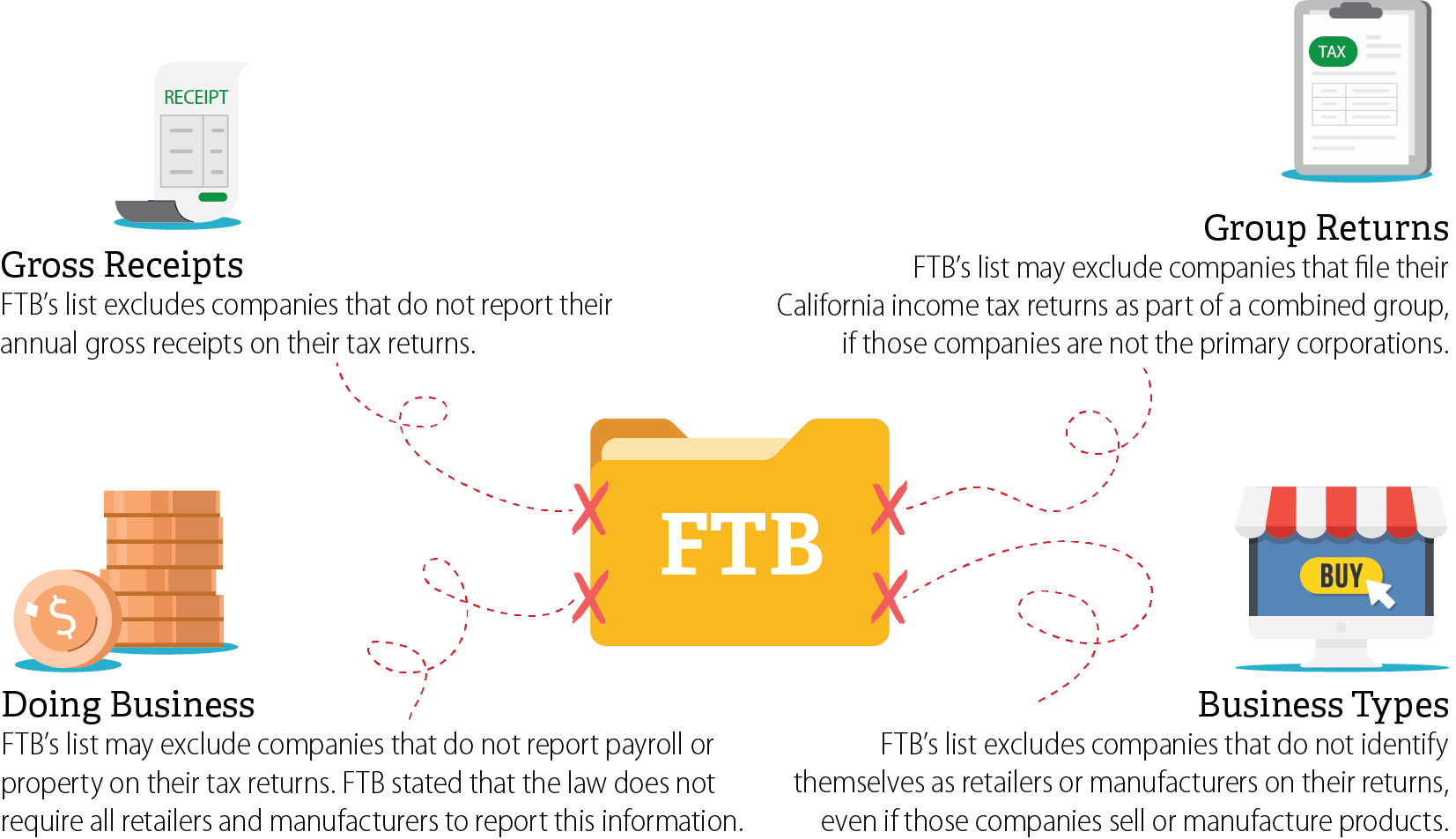

According to an attorney in FTB’s Legal Division, the list FTB generates may not be an accurate or complete representation of all companies subject to the Act because of limitations with the law and because tax returns do not contain some information necessary to create entirely accurate and complete lists. For example, the attorney noted that when multiple entities file a group tax return, FTB’s process identifies only the primary corporation for inclusion on its list. As a result, FTB’s list may not include a member of the group that has a reporting requirement under the Transparency Act. Further, when entities file a group tax return, each individual entity does not typically include its principal business activity code. Businesses use these activity codes to identify themselves as manufacturers or retailers. Figure 5 presents other reasons that FTB may not include companies on its list.

Figure 5

FTB’s List Omits Some Companies Because They Do Not Always Include Certain Information on Their Tax Returns

Source: Interviews with FTB staff and reviews of internal documentation.

FTB’s list excludes companies that do not report their annual gross receipts on their tax returns. FTB’s list may exclude companies that file their California income tax returns as part of a combined group, if those companies are not the primary corporations. FTB’s list may exclude companies that do not report payroll or property on their tax returns. FTB stated that the law does not require all retailers and manufacturers to report this information. FTB’s list excludes companies that do not identify themselves as retailers or manufacturers on their returns, even if those companies sell or manufacture products.

The provisions of the Transparency Act that dictate when FTB is to provide this list have further impaired the ability of the Attorney General’s Office to enforce the Act. The Transparency Act requires FTB to submit its list annually to the Attorney General by November 30 of each calendar year, based on tax returns FTB received as of December 31 of the prior year. In general, FTB has provided a list to the Attorney General’s Office every May before the deadline. Nevertheless, this means that the Attorney General’s Office has not received a list of companies that may be subject to the Transparency Act until nearly a year and a half after the end of a taxable year. For example, if FTB provides the Attorney General’s Office with a list in May 2021 for taxes filed in calendar year 2020, it will be from information from taxable year 2019 at the latest. As a result, by the time the Attorney General’s Office has the ability to review companies for compliance, some companies may have dissolved, may have otherwise ceased doing business, or may no longer be subject to the Transparency Act.

If the Legislature were to amend the Transparency Act to remove the requirement that FTB compile the list, the Legislature could authorize the Attorney General’s Office to establish another means of identifying companies that are subject to the Act. For instance, a team within the Attorney General’s Office currently enforces the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) without a list. Like the Transparency Act, the CCPA applies to companies that meet an income threshold and do business in California. The Attorney General’s Office proactively identifies companies that are not complying with the CCPA—for instance, by reviewing consumer reports. When we proposed eliminating the provision of the Transparency Act that requires FTB to generate a list of companies subject to the Act, neither FTB nor the Attorney General’s Office disagreed with this recommendation.

Regardless of whether the Legislature chooses to eliminate FTB’s role in generating a list, the Attorney General’s Office should take steps to increase consumers’ ability to distinguish companies on the merits of their efforts to address slavery and human trafficking in their supply chains. This would allow members of the public to use their purchasing power or direct advocacy to encourage companies to improve their business practices. However, state law protects tax return information from public disclosure, rendering the specific information contained in FTB’s list confidential. Consequently, consumers are not able to know which companies are subject to the Act and must proactively search through companies’ websites to identify whether those companies have transparency disclosures. In fact, when transparency advocacy organizations have contacted the Attorney General’s Office to obtain the list of companies that might be subject to the Act, the agency was unable to provide it to them because of this confidentiality.

The Attorney General’s Office maintains a website regarding the Transparency Act that contains general information, guidance on how companies can comply with applicable requirements, and a system by which the public can submit complaints. However, the website lacks a registry that would allow consumers to easily compare known disclosures. In contrast, other jurisdictions, such as Australia and the United Kingdom, have implemented website registries where consumers can examine and compare known disclosures. These public registries contain human trafficking transparency disclosures from mandated reporting entities as well as voluntary submissions from companies not subject to reporting requirements. Not only are consumers who use these registries better able to compare disclosures from different companies, but stakeholders interested in the effects of human trafficking can also consult the websites to determine whether certain businesses are complying with the law.

When we discussed this option with the Attorney General’s Office, it did not identify any issues with maintaining such a registry on its website as long as the Legislature directed it to do so, and it added that it would be beneficial to provide an opportunity for nonprofits and companies not explicitly subject to the Act to have their disclosures included. If the State made such changes to the Transparency Act, then expanding the Act to include tropical deforestation would enable both private consumers and state agencies to ensure that their purchases align with their values related to slavery, human trafficking, and tropical deforestation.

The Attorney General’s Office Has Not Examined Compliance With the Transparency Act Since 2016 and Is Limited in the Penalties It May Apply

The Attorney General’s Office has made limited efforts to ensure compliance with the Transparency Act, and it has few options for enforcement. In April 2015, the Attorney General’s Office notified businesses on FTB’s list that they might be subject to the Transparency Act. The agency also published guidance to assist companies in their efforts to comply with the Act. After notifying the businesses, the Attorney General’s Office reviewed websites of companies on FTB’s list from 2015 to 2016, and if the companies were not in compliance, the agency warned them that failure to comply within 30 days may result in an enforcement action.

State law provides the Attorney General’s Office with the authority to seek injunctive relief when companies have not complied with the disclosure requirements of the Transparency Act. In other words, the agency can sue a business and get a court order to require it to comply. However, the Attorney General’s Office stated that it did not identify an opportunity to use this enforcement power. According to the senior assistant attorney general (assistant attorney general), during the agency’s review of companies’ compliance from 2015 to 2016, the Attorney General’s Office identified 61 businesses that it believed to be subject to and in violation of the Act. The agency subsequently sent notices informing these companies of their noncompliance. The assistant attorney general stated that the agency considered taking action but that all companies eventually complied with the Act.

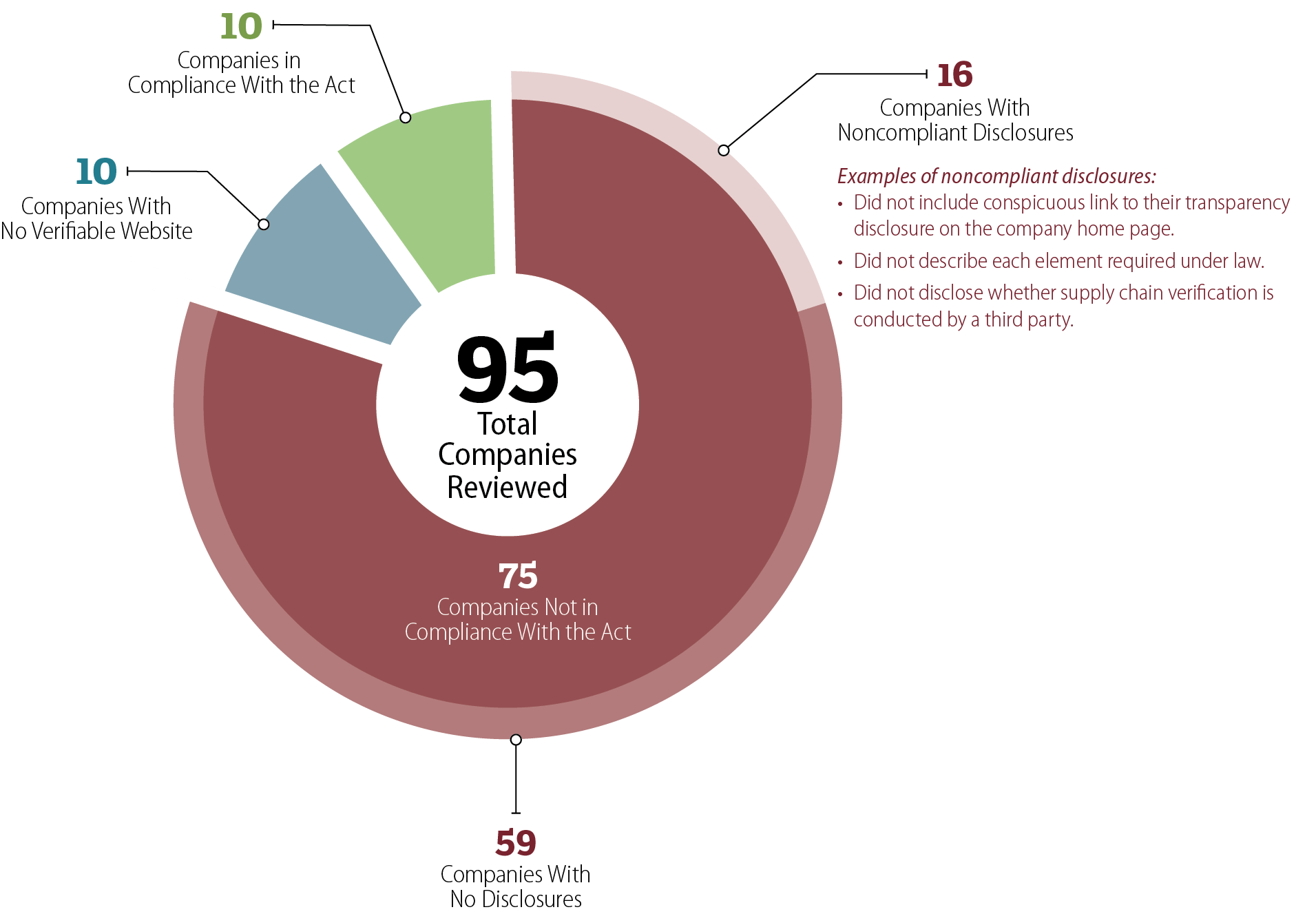

The assistant attorney general also explained that from the perspective of the Attorney General’s Office, the agency achieved 100 percent compliance when it performed enforcement activities from 2015 to 2016. When we reviewed the websites and disclosures for a random sample of 95 companies from FTB’s most recent list of more than 3,100 companies, based on tax returns from 2021, we found that 75 of the 95 companies we selected were not complying with the Transparency Act, as Figure 6 shows.8 As a result, consumers lack the information necessary to understand how certain companies may be addressing slavery and human trafficking in their supply chains. The assistant attorney general acknowledged that without a second round of enforcement, the agency could not determine the level of recent compliance.

Figure 6

More Than Three Quarters of the Companies We Reviewed Did Not Have Required Transparency Act Disclosures on Their Websites

Source: FTB’s list of companies subject to the Transparency Act and auditor observation of public company websites.

Of the 95 companies we reviewed, 59 companies had no disclosures, 16 companies had noncompliant disclosures, 10 had no verifiable website, and 10 were in compliance with the Act. Examples of noncompliant disclosures include disclosures that did not include conspicuous link to their transparency disclosure on the company home page, disclosures that did not describe each element required under law, and disclosures that did not disclose whether supply chain verification is conducted by a third party.

However, the Attorney General’s Office has not conducted external enforcement activity since 2016 to identify noncompliance with the disclosure requirements. According to the assistant attorney general, the agency did not conduct enforcement during this time because the Attorney General’s Office was required to redeploy available resources to adequately defend California in litigation brought by the federal government against the State or to initiate litigation to protect the State from harmful federal actions. In 2020 the agency considered conducting a second round of enforcement but determined that it had other priorities. According to the assistant attorney general, he believed until 2024 that FTB’s list of companies did not change much from year to year. The Attorney General’s Office therefore concluded that regularly testing companies for compliance was unnecessary. However, when we reviewed FTB’s lists for 2011 through 2021, in some instances we identified significant variances in the number of companies from one year to the next. For example, the list that FTB provided to the Attorney General’s Office in May 2023 contained about 300 more companies than the previous year’s list. After we discussed this issue with the Attorney General’s Office, the assistant attorney general reviewed the most recent lists and acknowledged the changes from year to year, citing how it had not compared lists when proposing enforcement in 2020.

Were it to conduct another round of enforcement activities, the Attorney General’s Office has the authority to take other steps to identify companies that are not compliant with the Transparency Act. Specifically, the Attorney General’s Office explained that when it identifies a company that may be in violation of the Transparency Act, it has the ability to request additional information—through issuing a subpoena, for example—regardless of whether that company is on FTB’s list. Nonetheless, the agency stated that is has never had the opportunity to exercise this ability. Further, the Transparency Act does not authorize the Attorney General’s Office to seek civil penalties in order to enforce its provisions. However, under another state law, a business that does not meet its legal obligations while other businesses do may be engaging in unfair competition, enabling the Attorney General’s Office to bring an action for civil penalties. A similar transparency initiative in Canada allows the government to levy specific fines of not more than $250,000 against companies that violate the provisions of the country’s transparency disclosures. According to an assistant attorney general, allowing the Attorney General’s Office to levy specific penalties and fines against noncompliant companies would be a valuable enforcement mechanism.

Finally, even companies that comply with the Transparency Act may not be giving consumers sufficient information to understand the companies’ efforts to combat human trafficking. Under existing state law, a company need only disclose that it is or is not taking certain actions to address the potential for human trafficking. However, the law does not require businesses to update their disclosures, and disclosures we reviewed were often undated. In our review of disclosures, we also noted that some companies attested to beginning to undertake supply chain oversight practices. Without dated disclosures or periodic updates, consumers cannot know whether a business is making a good faith effort to act on creating supply chain oversight practices. The assistant attorney general stated that requiring companies to include a revision date on their disclosures would be helpful because it would improve the ability of the Attorney General’s Office to monitor companies for compliance with the Transparency Act.

Other Areas We Reviewed

The Audit Committee requested that for the most recent year of the State’s procurement of goods and services, we determine the size and type of supplying businesses from which the State acquired raw or processed forms of forest-risk commodities, as well as the quantity of goods and services it acquired. To address these issues, we reviewed data in the State’s procurement system.

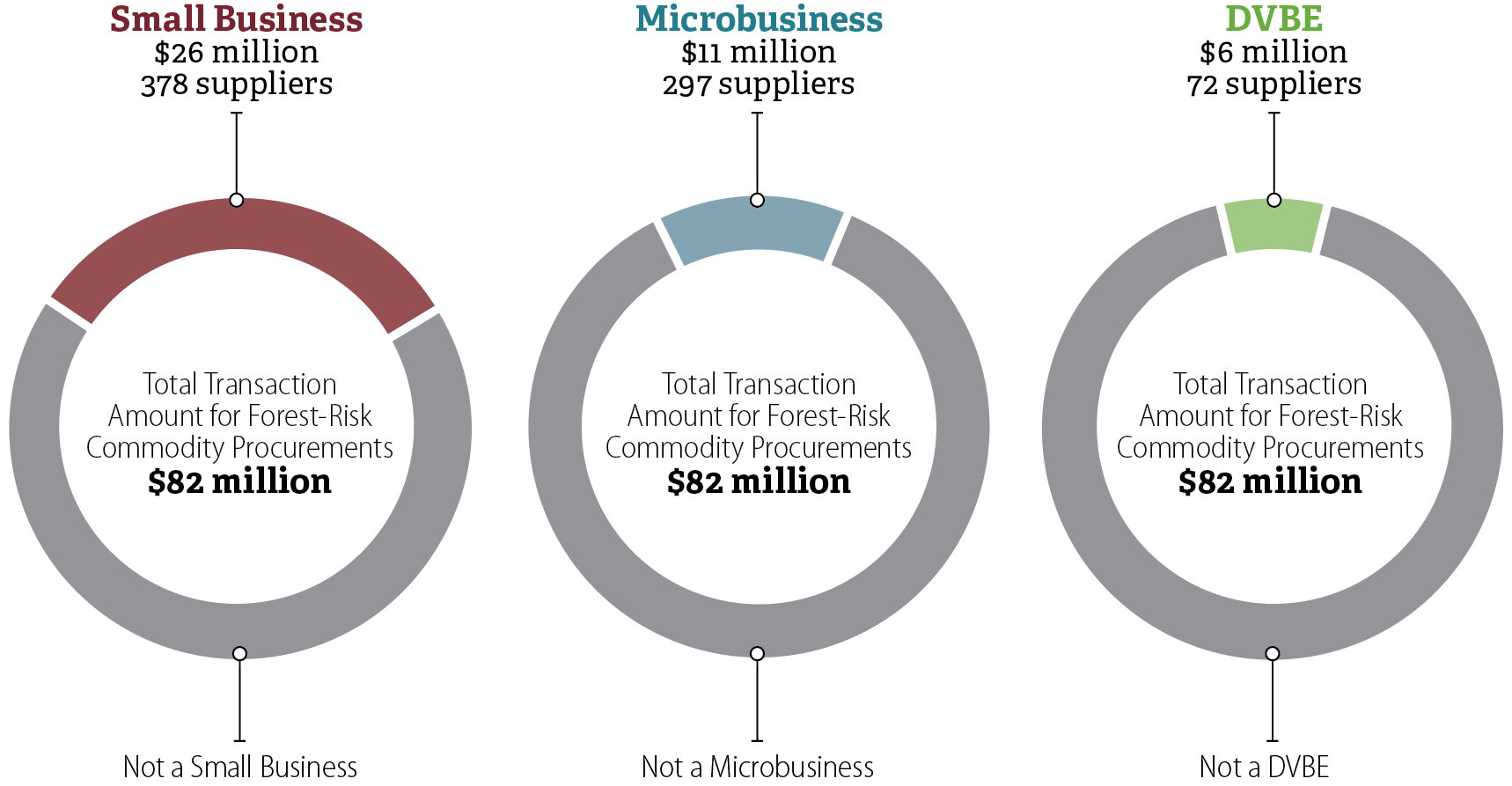

The State Procured Some of Its Forest‑Risk Commodities Through Small Businesses, Microbusinesses, and DVBEs

By identifying items through descriptions and standardized codes in the procurement system, we were able to obtain limited information related to the size and type of businesses from which the State procured forest-risk commodities. We found that in 2023, some of the State’s procurements of forest‑risk commodities—raw materials whose production in the tropics may be associated with deforestation—were from small businesses, microbusinesses, or businesses recognized as Disabled Veteran Business Enterprises (DVBEs), as the text box defines. As Figure 7 shows, about $26 million of these procurements—or 32 percent—involved small businesses. The data in the procurement system does not include information on the number of employees suppliers have or whether they are retailers or manufacturers, so we could not identify the size and type of suppliers by those attributes.

Key Requirements for Small Businesses, Microbusinesses, and DVBEs

Small Business: Either has average annual gross receipts of $18 million or less over the previous three years and employs 100 or fewer individuals, or is a manufacturer with 100 or fewer employees.

Microbusiness: Has had average annual gross receipts of $6 million or less over the previous three years, or is a manufacturer with 25 or fewer employees.

DVBE: Is at least 51 percent owned by disabled veterans and is managed and controlled by one or more disabled veterans.

Source: State law and DGS small business website.

Figure 7

The State’s Procurements of Forest-Risk Commodities in 2023 Involved Small Businesses, Microbusinesses, and DVBEs

Source: State procurement data.

Note: A single business can be certified as one or more of the categories above (small business, microbusiness, or DVBE). For example, microbusiness is a subset or designation of small business.

Of the $82 million in forest-risk commodity procurements, small businesses were involved in transactions totaling $26 million and involving 378 suppliers, microbusinesses were involved in transactions totaling $11 million and involving 297 suppliers, and DVBEs were involved in transactions totaling $6 million and involving 72 suppliers.

The Data in the Procurement System Do Not Provide the Detail Necessary to Aggregate the Quantity of Forest-Risk Commodities That the State Procured

The Audit Committee requested that we identify the quantity of forest-risk commodities the State acquired in 2023. Although we identified about 48,000 unique records of state agencies’ procuring goods and services containing forest-risk commodities in 2023, the available data do not provide the level of detail necessary to aggregate the quantity of goods and services the State procured through these records in a meaningful way. Although the procurement system identifies the total value of each contract, it uses different and inconsistent units of measurement for the commodities that are purchased. For example, purchased items with “wood” in the description could be measured in pounds, yards, pallets, or in multiple other units.

Recommendations

The following are the recommendations we made as a result of our audit. Descriptions of the findings and conclusions that led to these recommendations are presented in the sections of this report.

Legislature

If the Legislature determines that reducing the State’s possible contributions to tropical deforestation is a priority, the Legislature should improve the State’s commitment to sustainability by requiring DGS to expand its EPP program in the following ways:

- Amend the authorizing statute for EPP to explicitly include tropical deforestation as program criteria.

- Expand DGS’s list of recommended third-party certifications to include certifications that eliminate or reduce procurement of products that contribute to tropical deforestation.

- Develop specific goals for the State’s procurement of EPP products and services.

To better empower consumers to base their purchasing decisions on companies’ efforts to eliminate slavery and human trafficking from their supply chains, the Legislature should amend the Transparency Act in the following ways:

- Eliminate the provision that requires FTB to supply to the Attorney General’s Office a list of the companies that must comply with the Act.

- Revise the provisions that determine which companies are subject to the Act, such that it no longer depends on tax return information that necessitates the involvement of FTB. For example, it could align the Act with similar provisions in the CCPA. Specifically, it could require that the Transparency Act apply to companies that operate in California and maintain an annual gross revenue in excess of $25 million.

- Authorize the Attorney General’s Office to use additional enforcement measures as necessary to achieve the goals of the Act by issuing administrative penalties, empower the agency to access records needed to determine whether a company is subject to the Act, and enable the Attorney General’s Office to investigate possible violations of the Act upon receiving a sworn complaint or on its own initiative.

- Require companies to disclose on their websites the dates their disclosures were last updated.

- Require the Attorney General’s Office to identify and publish all known Transparency Act disclosures as a public registry on its website by August 2025.

- If the Legislature first addresses the weaknesses in the Act, require companies that are subject to the Transparency Act to include in their public transparency disclosures their efforts, if any, to eliminate tropical deforestation from their supply chains.

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards and under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by Government Code section 8543 et seq. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on the audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

August 27, 2024

Staff:

John Lewis, MPA, CIA, Audit Principal

Nicholas Sinclair, Senior Auditor

Logan Blower

Rachel D’Agui, MA

Data Analytics:

Ryan Coe, MBA, CISA

Brandon Clift, CPA

Legal Counsel:

JudyAnne Alanis

Joe Porche

Appendices

Appendix A—Selected Guidance From France’s National Strategy to Combat Imported Deforestation

Appendix B—Scope and Methodology

Appendix A

Selected Guidance From France’s National Strategy to Combat Imported Deforestation

France’s National Strategy to Combat Imported Deforestation includes documentation providing guidance to government officials on the procurement of public goods that may contribute to deforestation. This guidance includes the following:

- Informing purchasers of the risks associated with certain commodities.

- Aligning purchasing decisions with national goals and international commitments.

- Prioritizing the procurement of food services that offer diverse sources of protein.

- Assessing the necessary quantity of the commodities and studying their alternatives if raw materials or processed products are used in certain at‑risk commodities.

- Favoring unprocessed products over processed products, which often contain palm oil.

- Considering third-party certifications when procuring certain products and raw materials, such as cocoa and coffee.

- Using recycled paper and products derived from wood that are sustainably produced.

- Preferring tires that will last a minimum distance traveled and are fuel-efficient, and favoring retreading over replacing tires.

- Requiring that winning bidders complete a traceability questionnaire that takes into consideration the risk of deforestation in the delivery of the service. Have winning bidders propose a plan for reducing the risk of deforestation associated with their importations and establish an annual report that in part assesses the risk of deforestation associated with the agreement.

Appendix B

Scope and Methodology

The Audit Committee directed the California State Auditor to conduct an audit to determine whether the State is inadvertently contributing to tropical deforestation through its procurement of goods and services. In addition, the Audit Committee asked us to review the implementation and enforcement of the Transparency Act. This table lists the objectives that the Audit Committee approved and the methods we used to address them. Unless otherwise stated in the table or elsewhere in the report, statements and conclusions about items selected for review should not be projected to the population.

Assessment of Data Reliability

The U.S. Government Accountability Office, whose standards we are statutorily obligated to follow, requires us to assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of computer-processed information we use to materially support our findings, conclusions, or recommendations. In performing this audit, we relied on electronic data obtained from DGS’s procurement system for 2023. To evaluate the data, we reviewed existing information, interviewed people knowledgeable about the data, and performed electronic testing of key elements.

During our evaluation, we identified problems with the procurement system for the purpose of identifying forest-risk commodities. The procurement system does not specifically track forest-risk commodities or identify the raw materials used to manufacture each product the State purchased. Additionally, because the procurement system allows multiple types of units of measurement to be used, we found that there was not a consistent or precise unit of physical measurement that we could use to identify the quantity of items containing forest-risk commodities. Consequently, we found that the procurement system was not sufficiently reliable for the purposes of analyzing forest-risk commodities procured, including the quantity of goods and services acquired and the dollar value of the procurements. Notwithstanding these limitations, the data in the procurement system represents the best source of information on the State’s procurements in 2023. Although this determination may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

We also relied on data obtained from FTB’s electronic list of companies subject to the Transparency Act to randomly select a sample of 95 companies for testing compliance with the Act. We performed data-set verification procedures and electronic testing of key data elements and identified multiple blank fields and seven duplicate companies. We did not perform completeness testing of the data because the auditee stated that the data will likely never be complete as a result of the limited tax return information available to FTB. Consequently, we found the electronic data were not sufficiently reliable for the purposes of selecting companies as a sample for testing compliance with the Transparency Act. Notwithstanding these limitations, we relied on the data from FTB’s electronic list of companies because that data is historically what the Attorney General’s Office used to conduct its enforcement activities related to the Transparency Act. Although this determination may affect the precision of the numbers we present, there is sufficient evidence in total to support our findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

Response to Audit

Department of Justice

August 8, 2024

VIA EMAIL ONLY

Grant Parks

California State Auditor

621 Capitol Mall, Suite 1200

Sacramento, CA 95814

RE: California State Auditor Report 2023-123; Draft Audit Response—Tropical-Forest-Risk Commodities

Dear Mr. Parks: We appreciate your review of the intent, requirements, and efficacy of SB 657, the Transparency in Supply Chains Act (“the Act”), and your perspectives on the California Department of Justice’s implementation of the bill in its current form. We concur with your recommendations regarding the need for substantive amendments to SB 657 in order to achieve better transparency and more comprehensive and effective awareness of companies’ efforts to eradicate human trafficking and slavery within their supply chains so that consumers are able to make fully informed decisions. Should the Legislature successfully pursue amendments to the Act in accordance with the recommendations in your report and should the necessary resources be available to carry out the recommendations, the California Department of Justice would be able to engage in further implementation of the Act.

If you have any questions or concerns regarding this matter, you may contact me at the telephone number listed above.

Sincerely,

DANIELLE F. O’BANNON

Chief Assistant Attorney General

Public Rights Division

For

ROB BONTA

Attorney General

Footnotes

- The USEIA is part of the U.S. Department of Energy and is a principal agency responsible for collecting, analyzing, and disseminating energy information to promote sound policymaking, efficient markets, and public understanding of energy and its interaction with the economy and the environment. ↩︎

- The data in DGS’s procurement system represent different types of transactions, including acquisitions, purchases, authorized work orders, and awarded contracts. We refer to all of these transactions as procurements in this report. ↩︎

- This review consisted of an electronic search and a manual review of the results during which we excluded items that did not appear to clearly involve a forest-risk commodity. For example, although we initially identified an item described as paper clips because the description included the term paper, we excluded it because it does not actually contain paper. ↩︎

- Although the State also procures some ethanol and biodiesel, current state guidelines discourage the use of these fuels. As a result, ethanol and biodiesel accounted for a small amount of the biofuels the State procured in 2023. We consequently focused our review on the possible contributions to tropical deforestation and human rights violations resulting from the State’s procurement of renewable diesel. ↩︎

- Providers of transportation fuels must demonstrate that the mix of fuels they supply for use in California meets LCFS carbon intensity standards. The carbon intensity scores assessed for each fuel are compared to a carbon intensity benchmark for each year. Low carbon fuels below the benchmark generate credits, while fuels above the benchmark generate deficits. A deficit generator meets its obligation by ensuring that the amount of credits it earns or otherwise acquires from another party is equal to or greater than the deficits it has incurred. ↩︎

- A voluntary and non-legally binding political declaration that was developed by the United Nations Secretary-General’s Climate Summit held in New York in 2014. ↩︎

- The phrase tropical deforestation does not occur in state statute, regulations, the SCM, or the SAM, as of June 2024. ↩︎

- If we were unable to identify a website or disclosure on a company’s website, we used electronic keywords searches for terms associated with the Act, such as slavery, human trafficking, and supply chain, to ensure that the disclosures did not exist. ↩︎