2023-123 California’s Systems of Public Higher Education

Streamlining the Community College Transfer Process Could Increase Access

to Bachelor’s Degrees

Published: September 24, 2024Report Number: 2023-123

September 24, 2024

2023‑123

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the State’s three systems of public higher education: the California Community Colleges (CCC), the California State University (CSU), and University of California (UC). Our assessment focused on these systems’ efforts to improve the rate of community college transfers to CSU and UC. In general, we determined that streamlining the community college transfer process could increase students’ opportunities to earn bachelor’s degrees.

Although most transfer students who applied to CSU and UC gained admission to at least one campus in those systems, CCC students still struggle to transfer. Only about 1 in 5 students who began community college from 2017 to 2019 and intended to transfer did so within four years, and transfer rates were even lower for students from certain regions and demographic groups. The vast majority of students who did not transfer never reached the point of applying to CSU or UC, mainly because they had not earned enough units. The three systems could help increase transfer rates by improving the outreach and support they provide to transfer-intending students. For example, CCC could ensure that students receive counseling and develop education plans so that they have a clear roadmap for transferring. The three systems could also share data about transfer students to help campuses make more targeted outreach efforts. Additionally, for students who earn enough units to transfer, CSU and UC could facilitate access to their preferred degree programs by ensuring that competitive campuses and majors adequately prioritize transfer applicants for admission.

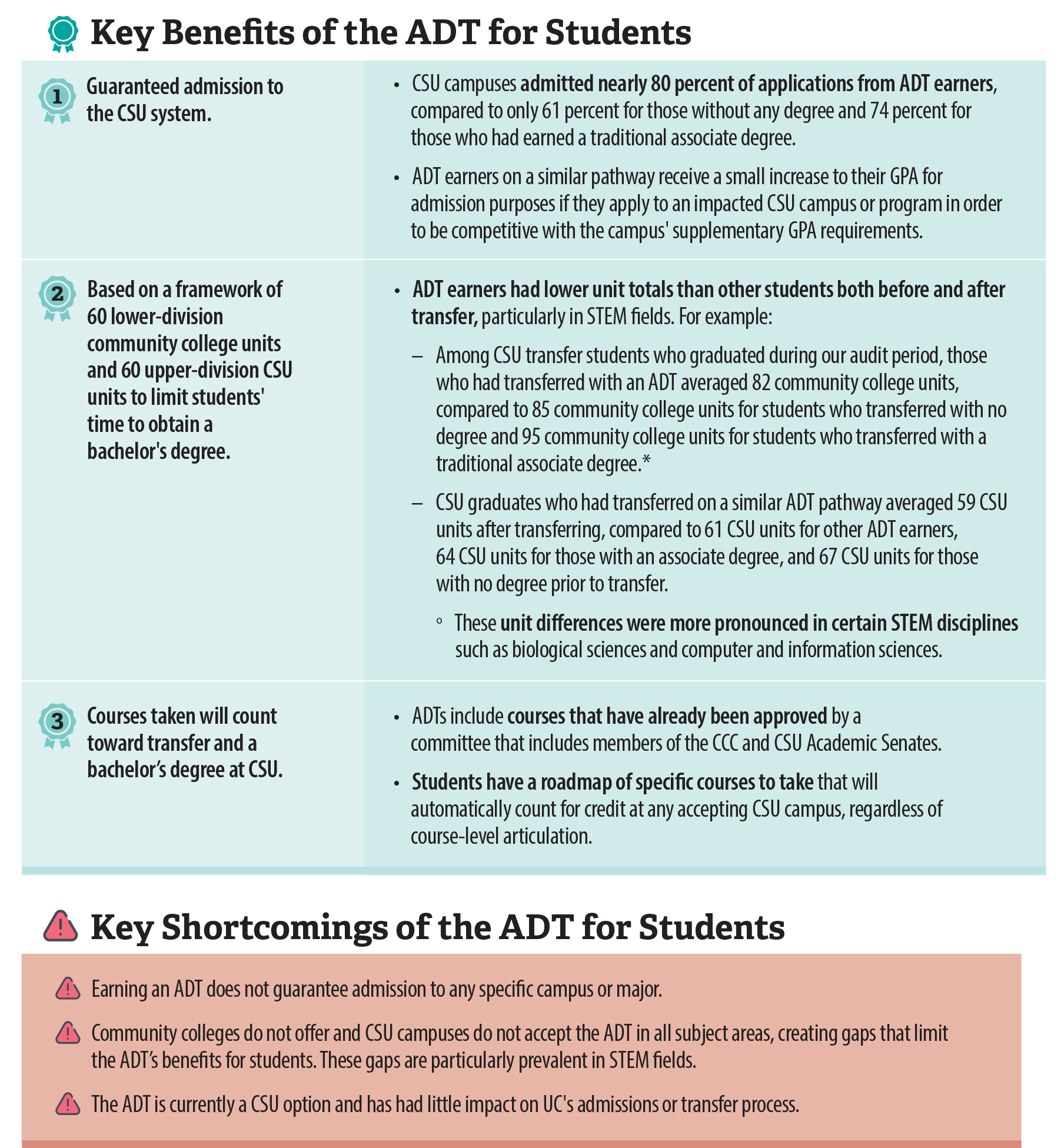

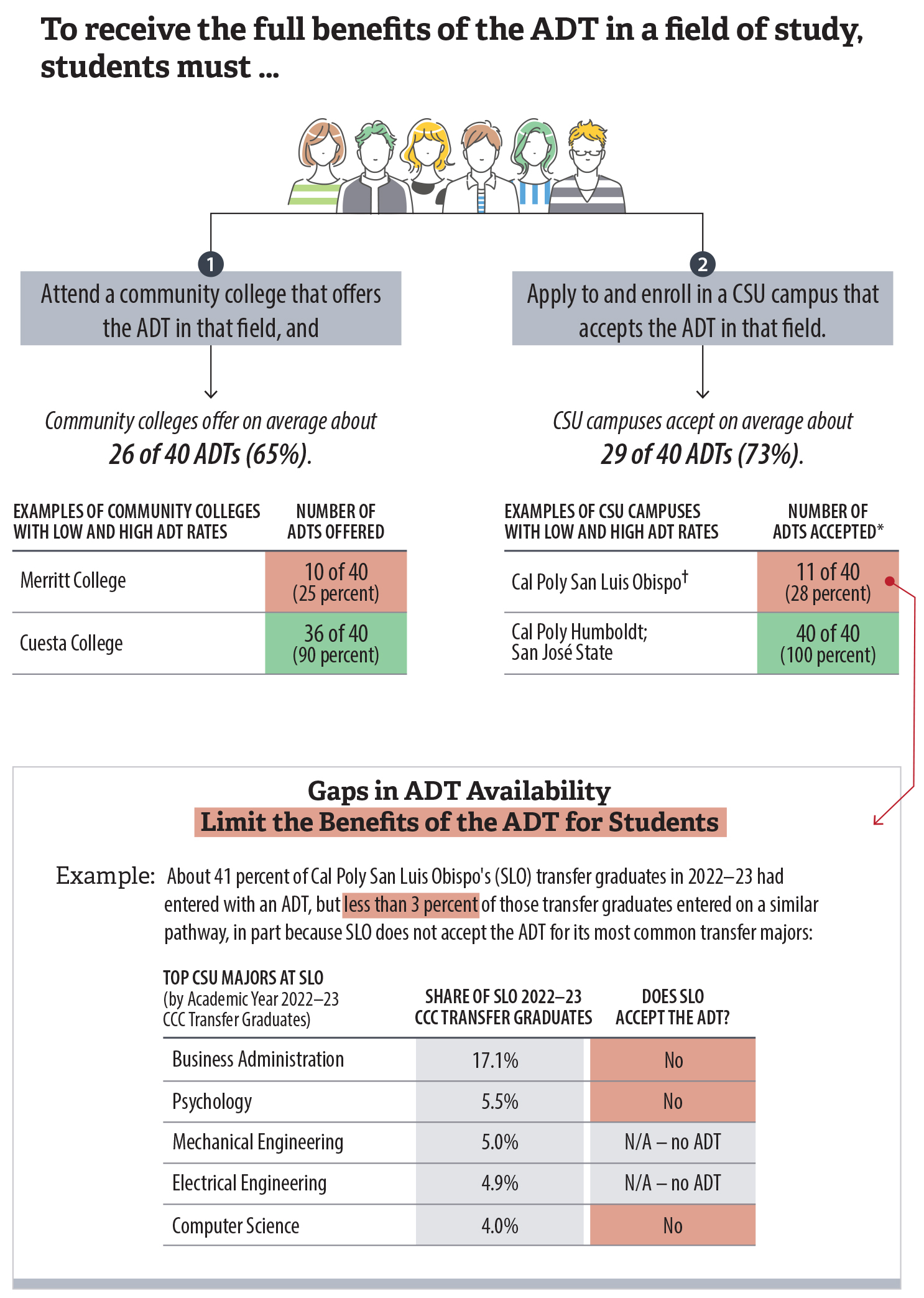

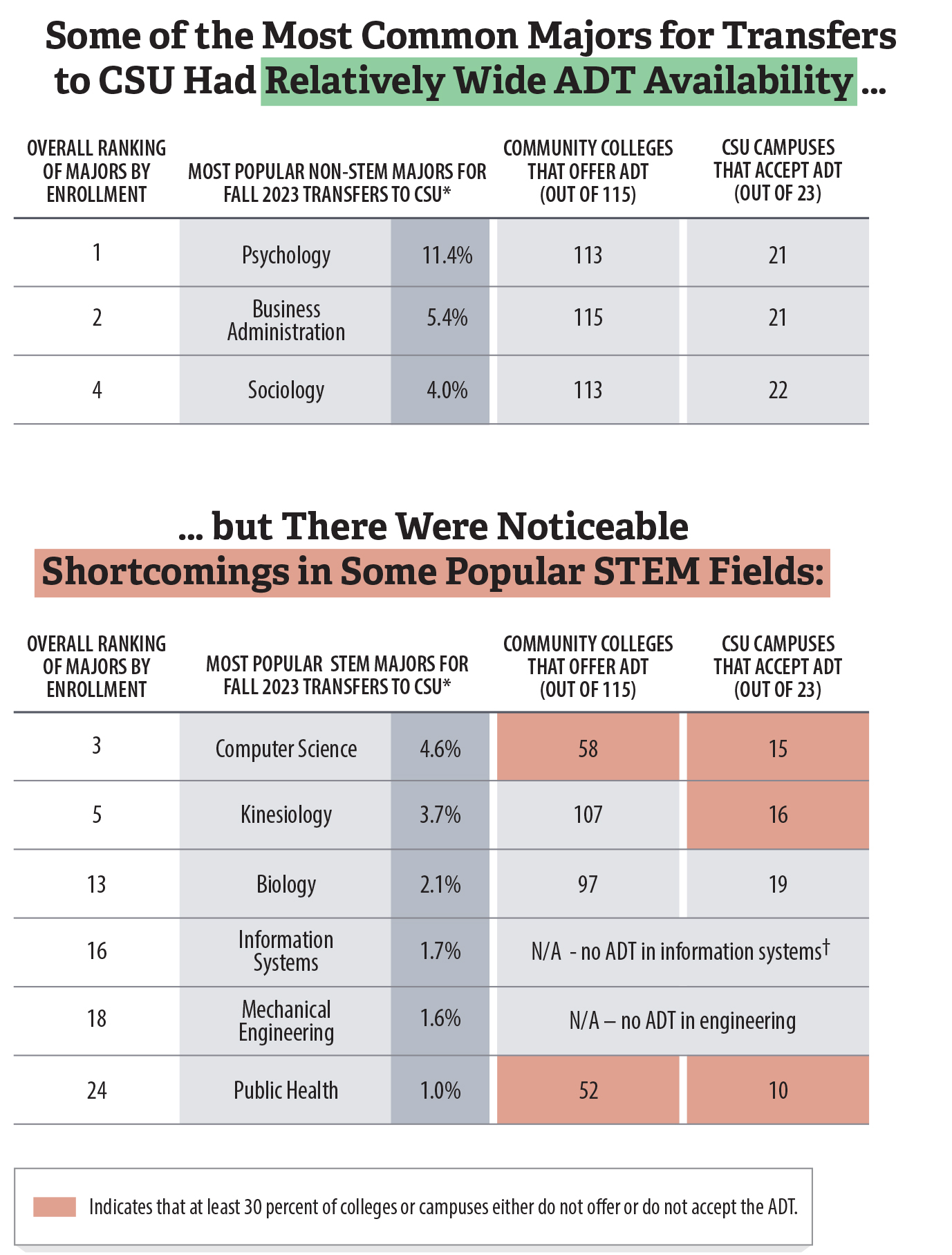

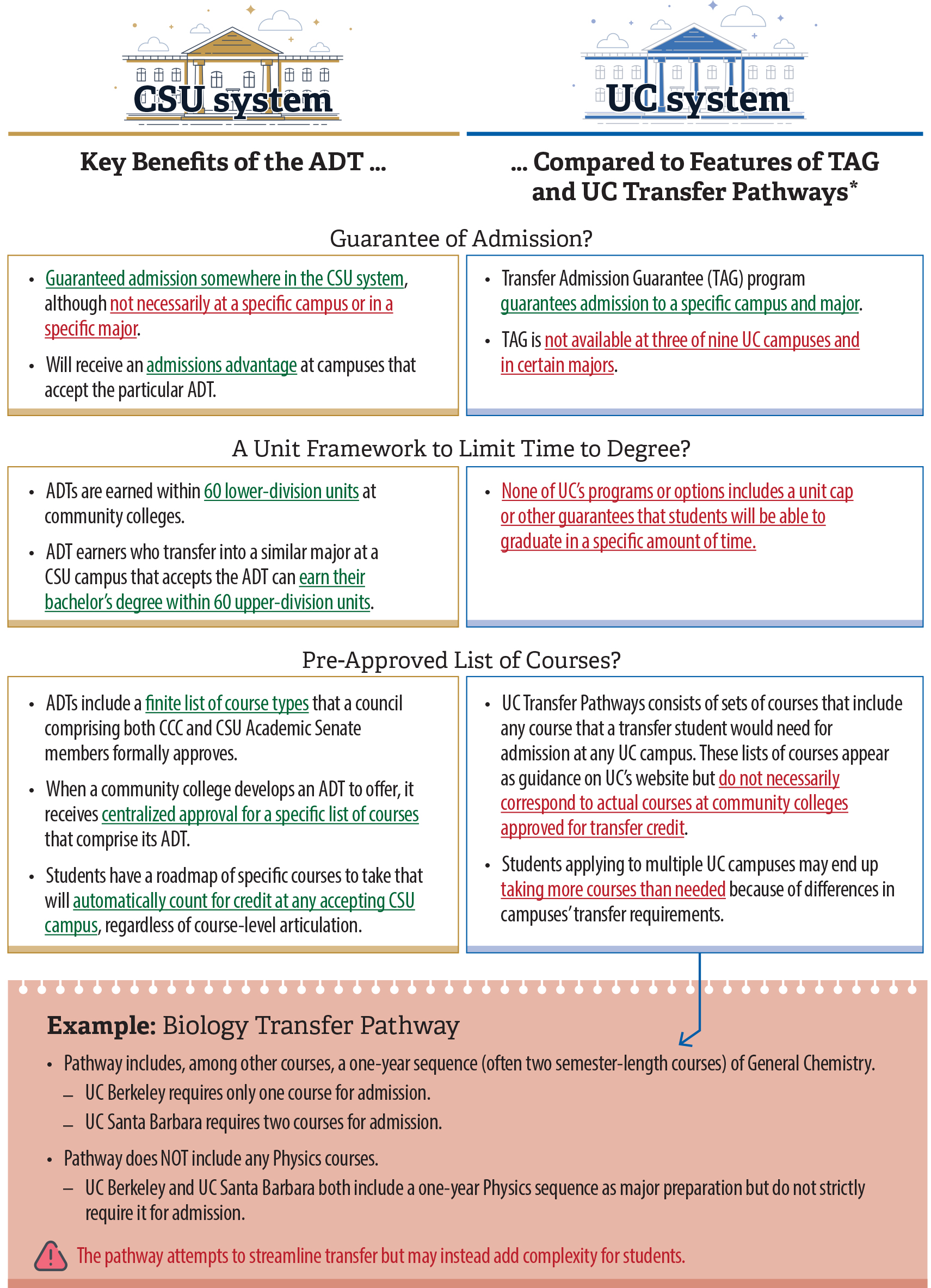

Another barrier to transfer is the variation in transfer requirements across and within the three systems, which makes the process difficult for students to navigate. The Associate Degree for Transfer (ADT) offers a streamlined transfer pathway to CSU. However, community colleges may not offer every ADT, CSU campuses may not accept every ADT, and UC has established its own transfer options that lack some of the ADT’s key benefits. Expanding the use of the ADT—or the use of a UC option that emulates its benefits—would further streamline the transfer process.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| ADT | Associate Degree for Transfer |

| ASSIST | Articulation System Stimulating Interinstitutional Student Transfer |

| CCC | California Community Colleges |

| C-ID | Course Identification Numbering System |

| CSU | California State University |

| EOPS | Extended Opportunity Programs and Services |

| FERPA | Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 |

| GPA | grade point average |

| STEM | science, technology, engineering, and mathematics |

| TAG | Transfer Admission Guarantee |

| UC | University of California |

Summary

Results in Brief

Each of the State’s three systems of public higher education—the California Community Colleges (CCC), the California State University (CSU), and the University of California (UC)—plays a critical role in helping Californians attain bachelor’s degrees. Since the publication of the Master Plan for Higher Education in California in 1960, the State has sought to develop and strengthen pathways for students to transfer from community colleges to CSU and UC campuses. Nevertheless, the transfer process remains difficult for students to navigate for a variety of reasons, including differences among the State’s three higher education systems.

The State’s Three Higher Education Systems Have Struggled to Meet Some Key Goals Related to Student Transfers

Only about 21 percent of community college students who began college from 2017 to 2019 and intended to transfer did so within four years, and transfer rates were even lower for students from certain demographic groups and regions of the State. Of the students who reached the point of applying to CSU or UC, more than 90 percent of CSU transfer applicants and more than 75 percent of UC transfer applicants gained admission to at least one campus in those respective systems, demonstrating relatively broad access for transfer students. However, transfer applicants’ access to competitive campuses and majors was more limited, which CSU and UC could address through additional monitoring to ensure that these campuses and majors are adequately prioritizing transfer students for admission.

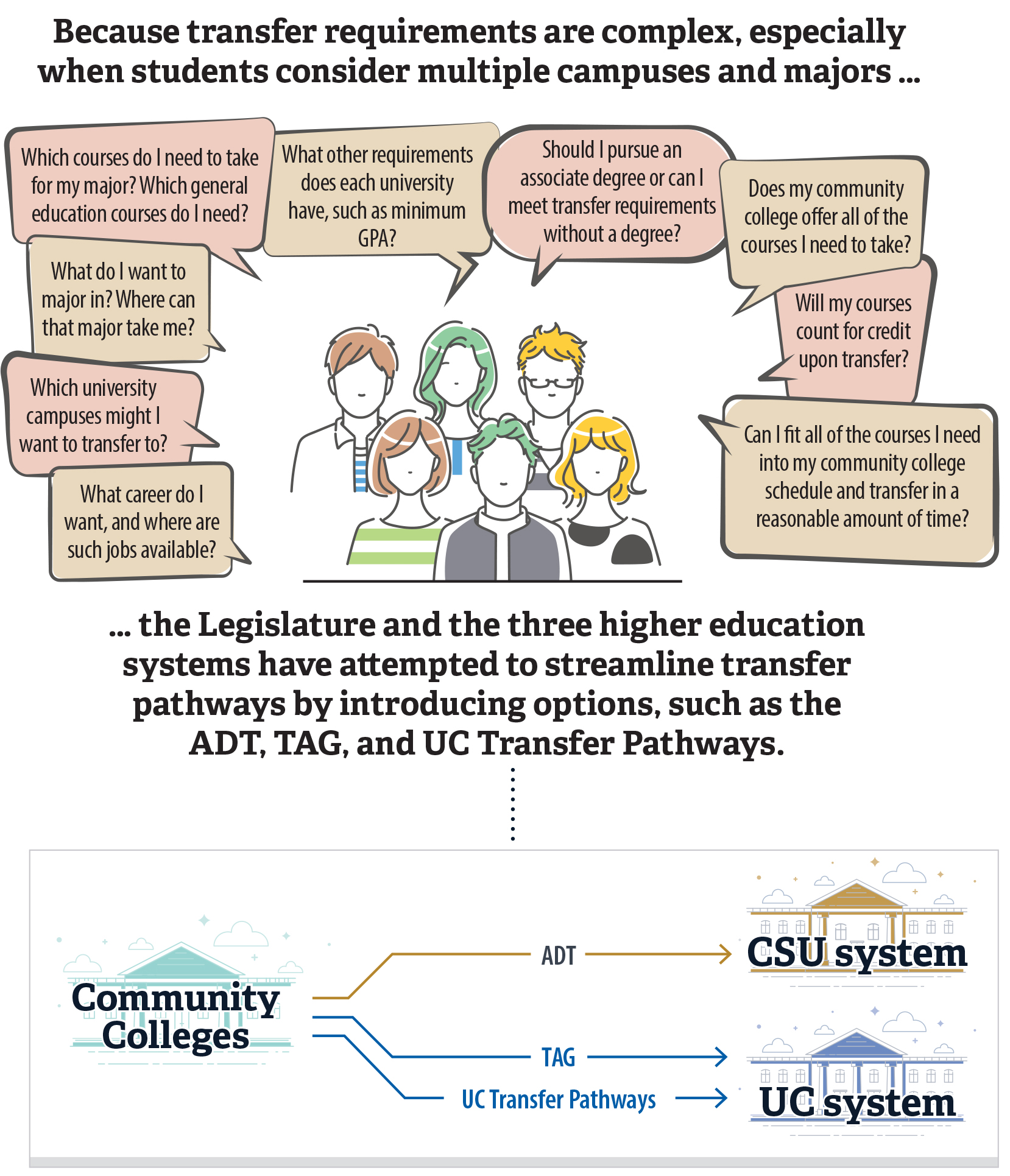

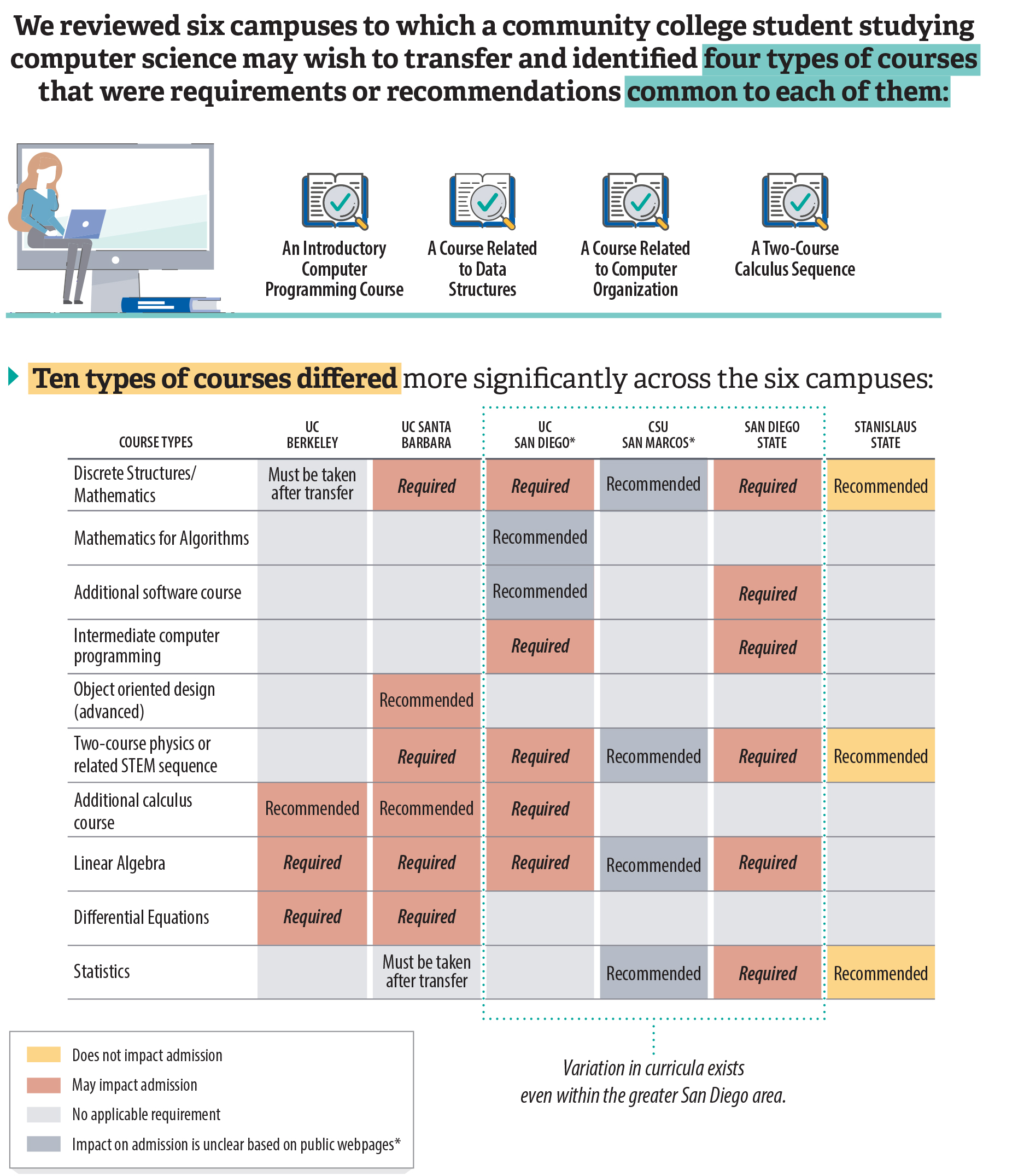

Variations in Requirements Across and Within the Three Systems Add Significant Complexity to the Transfer Process

Students who intend to transfer from California’s community colleges must navigate a complex series of decisions related to varied CSU and UC requirements, especially if those students are considering multiple campuses or majors. To try to minimize this complexity, the Legislature and the three higher education systems have designed specific transfer options. For example, the Associate Degree for Transfer (ADT) offers a streamlined transfer pathway to CSU campuses, as well as other benefits. However, this option’s impact is lessened because each community college may not offer every ADT, and each CSU campus may not accept every ADT. Further, UC has not yet widely adopted the ADT model. Instead, it has established its own transfer options that do not provide the same level of benefits as the ADT does.

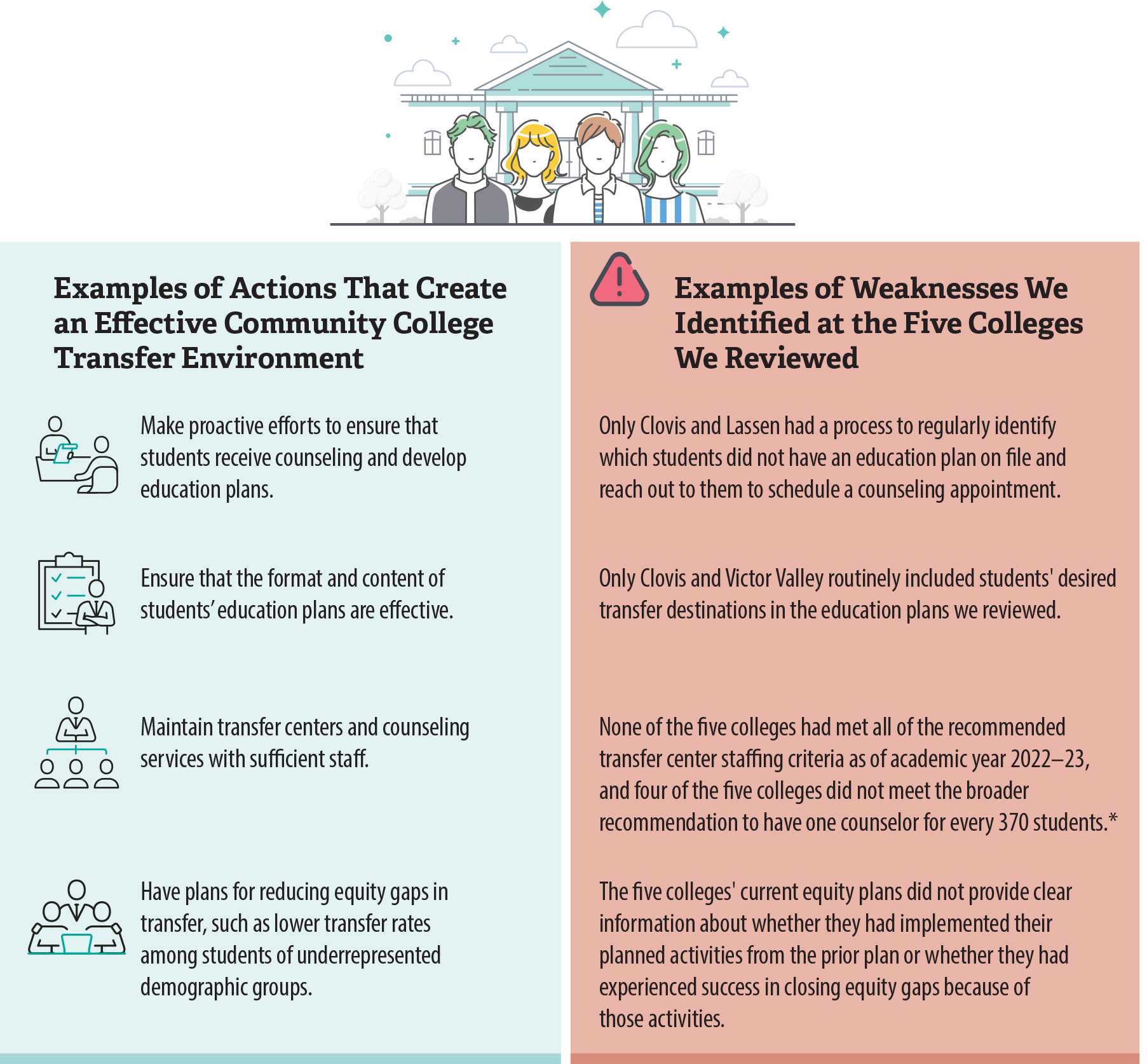

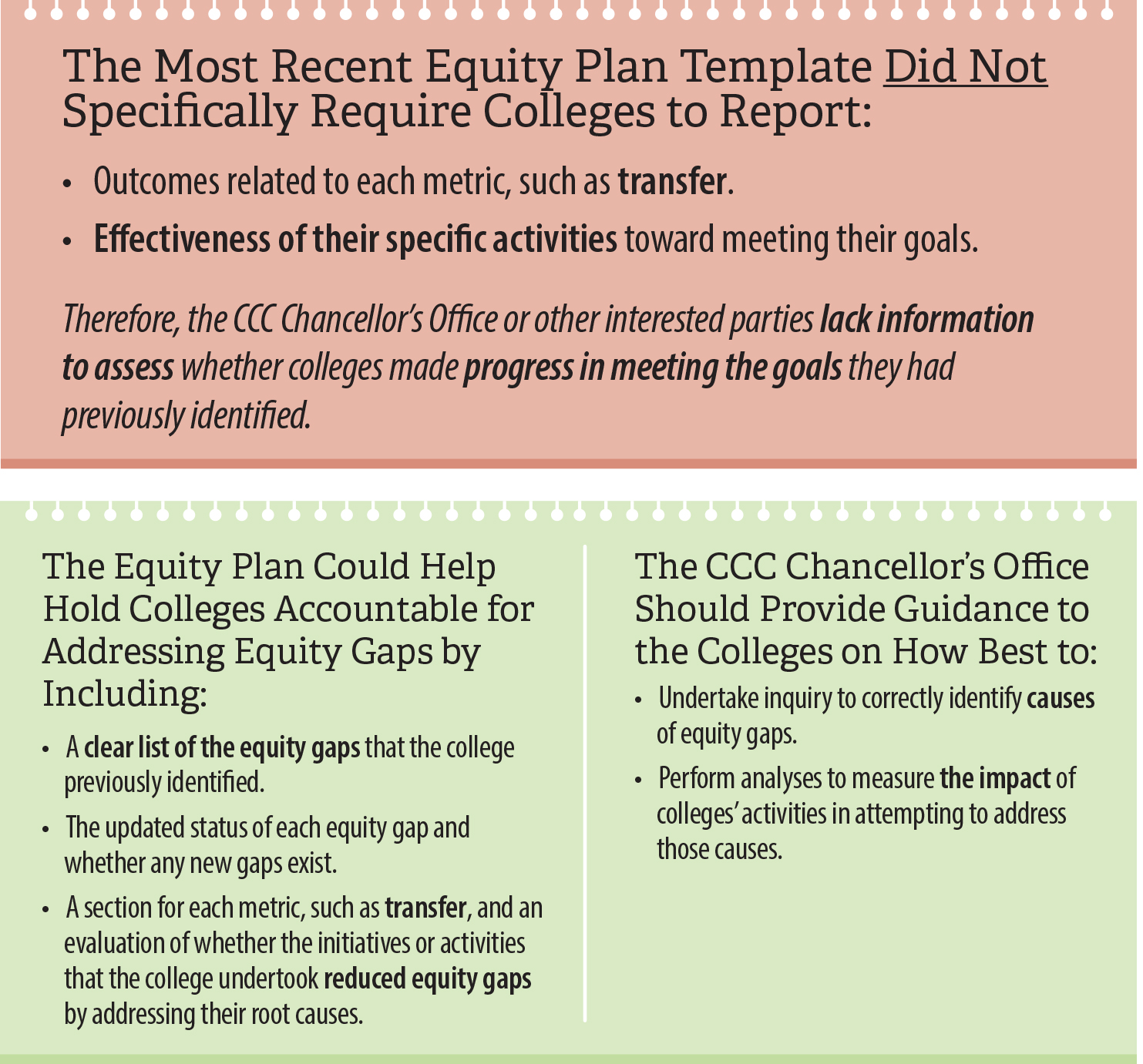

The Three Systems Could Better Facilitate the Transfer Process by Increasing Outreach and Support

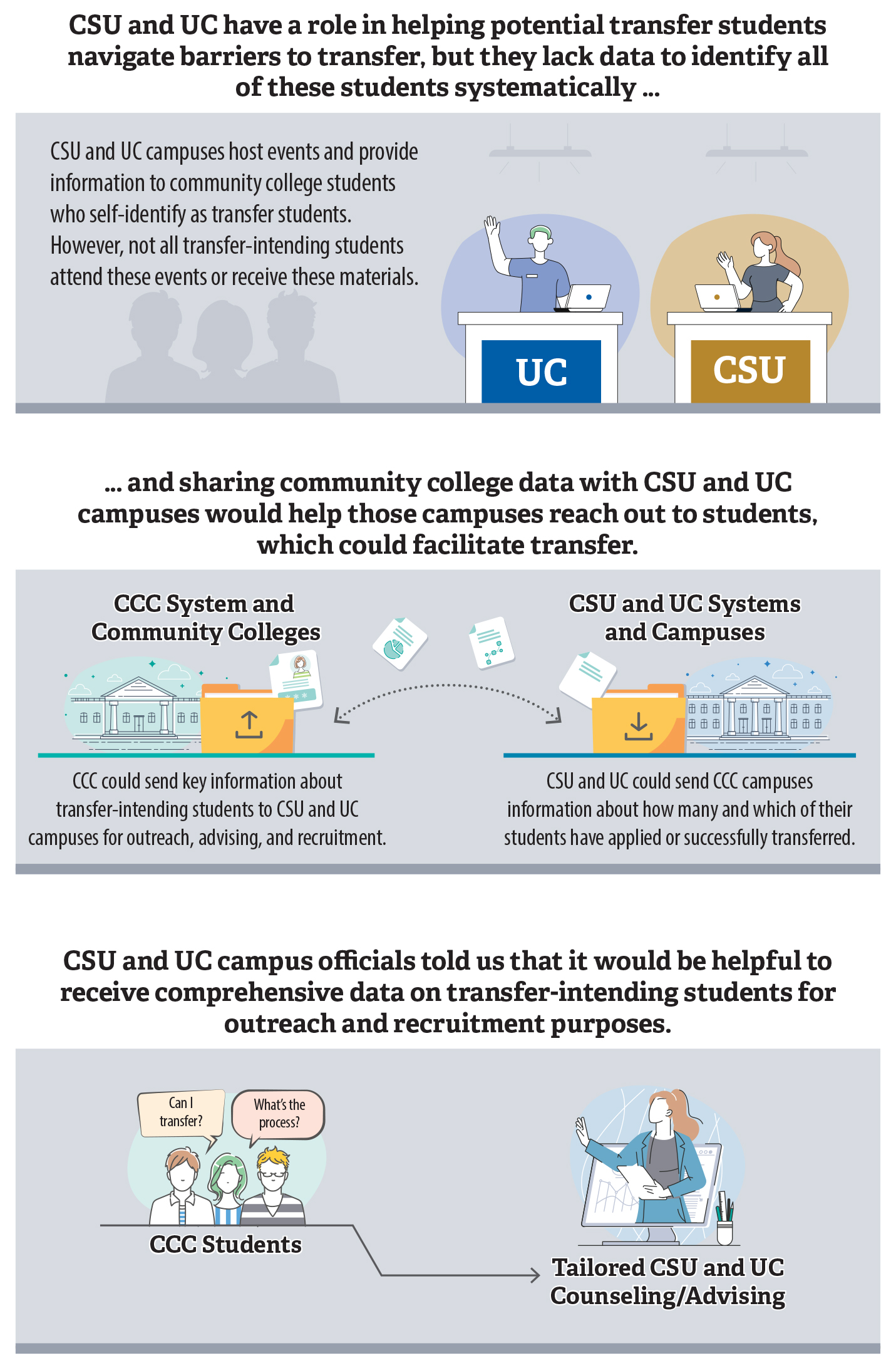

Outreach and support from all three systems are key to ensuring that community college students can successfully transfer. Nonetheless, the five community colleges we reviewed had some weaknesses in their processes for supporting students to help them transfer. Further, although CSU and UC have existing programs and methods for advising community college students about the transfer process, these efforts do not reach all transfer‑intending students. Expanding data sharing among the three systems would help improve their outreach efforts.

Agency Comments

The CCC Chancellor’s Office, the CSU Office of the Chancellor, and the UC Office of the President indicated they would take action to implement our recommendations. Because we did not make recommendations to the specific campuses we reviewed, we did not request them to respond.

Introduction

Background

During the past several decades, the attainment of a bachelor’s degree has become increasingly associated with positive outcomes, such as higher income and lower unemployment rates. According to a March 2023 report from the Public Policy Institute of California, a worker with a bachelor’s degree in California in 1990 earned an average of 39 percent more than one with only a high school diploma. In 2021, this difference had grown to 62 percent. Moreover, research suggests that California will face a significant lack of college‑educated workers within the next decade. To address such concerns, the Governor set a goal in 2022 to increase the percentage of working‑age Californians who have a postsecondary degree or certificate from 55 percent to 70 percent by 2030.

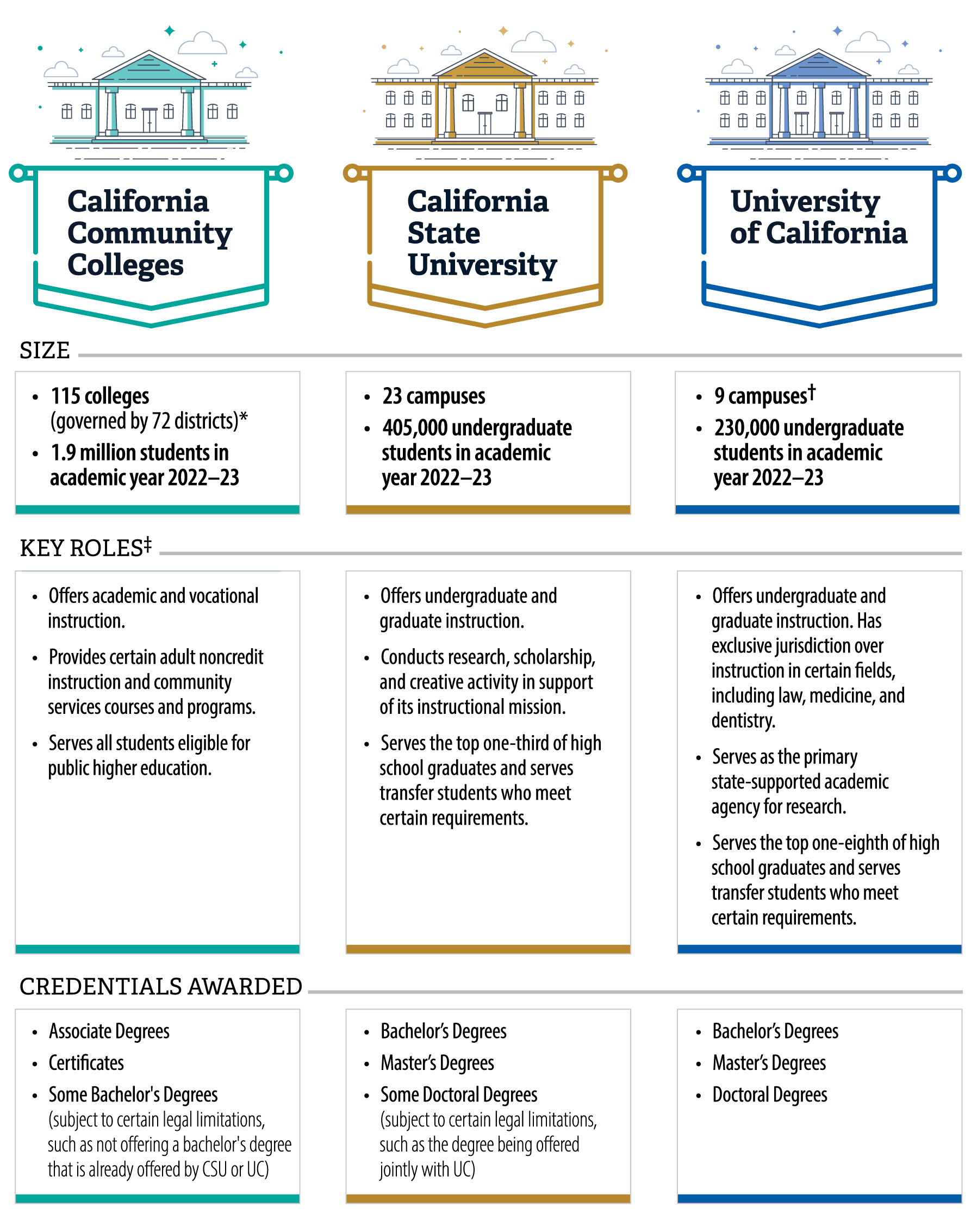

Although some students attend private universities, eight out of every 10 college students in California attend a public institution in one of the State’s three systems of higher education: the California Community Colleges (CCC), the California State University (CSU), and the University of California (UC). Figure 1 shows these systems’ sizes, roles, and degree types. As we discuss in the sections that follow, all three systems are critical to creating paths for Californians to attain college degrees.

Figure 1

California’s Three Systems of Higher Education Are Intended to Serve Different Purposes

Source: State law, the Master Plan, and reports and data from the systems about their campuses and undergraduate populations.

* We have not included Calbright College, a fully online public community college, because it does not offer courses that transfer to other colleges, nor does it confer associate degrees.

† We have not included the University of California, San Francisco, because it does not provide undergraduate instruction.

‡ The 1960 Master Plan envisioned these roles, including that UC would accept community college transfer students with at least a 2.4 GPA and that CSU would accept transfer students with at least a 2.0 GPA. In practice, transfer admissions requirements can be complex, as we discuss in Chapter 2.

Figure 1 is a vertical chart that describes basic details about and explains the key roles of each of California’s three systems of public higher education: the California Community Colleges, the California State University, and the University of California. The California Community Colleges is the largest system, consisting of 115 colleges and serving 1.9 million students in academic year 2022-23, whereas the California State University has 23 campuses and served 405,000 undergraduate students, and the University of California has nine campuses and served 230,000 undergraduates. The figure also shows that community colleges offer academic and vocational instruction to all students eligible for public higher education and generally award associate degrees and certificates. The California State University and University of California offer undergraduate and graduate instruction and generally award bachelor’s degrees, master’s degrees, and doctoral degrees.

The Master Plan for Higher Education in California

Published in 1960, the Master Plan for Higher Education in California (Master Plan) is essentially an agreement between the State and the three public systems of higher education. The Master Plan serves as a framework to differentiate the mission of each system and to provide all Californians with the opportunity to access higher education. The Master Plan states that UC should draw from the top one‑eighth of the high school graduating class and CSU from the top one‑third. Community colleges must admit any high school graduate. Because of this policy—along with affordable tuition, a broad array of educational and workforce training options, and 115 colleges across the State—community colleges currently serve more students than do CSU and UC combined.

Although the Master Plan and state law require CCC, CSU, and UC to collaborate, significant separation and autonomy exists both across and within the three systems. The Master Plan recommended that one council oversee and coordinate higher education efforts, but no permanent body has served this purpose since 2011. At that time, then‑Governor Brown vetoed funding for the California Postsecondary Education Commission—essentially disbanding it—because he believed it had been ineffective. Further, the three systems are not responsible to the same authority. Unlike CCC and CSU, UC’s independence is enshrined in the State’s Constitution, and it is therefore not subject to the same level of legislative control.

Within each system, statewide governance is the product of at least three bodies: a governing board, a faculty senate, and a central administrative office. The text box describes the responsibilities of these bodies. CCC is especially decentralized because 72 local community college districts, each containing from one to nine colleges, are governed by locally elected boards that have significant authority to set policy within their own districts.

The Higher Education Systems’ Statewide Governance Consists of Three Bodies

CCC, CSU, and UC each have the following:

- A governing board that sets policy, establishes requirements, and provides guidance for the system.

- A faculty senate that has certain authority over curriculum and other issues of educational policy.

- A central administrative office that manages and oversees the system.

Source: Analysis of state law and system policies and websites.

The Role of Transfer

The Master Plan emphasized transfer from community colleges, which primarily provide lower‑division education, to CSU and UC, which provide both lower‑ and upper‑division education.1 In fact, to ensure adequate capacity and lower the costs to educate each student, the Master Plan envisioned increasingly shifting students away from CSU and UC and into community colleges for their lower‑division education. When the Master Plan was published in 1960, about 55 percent of the State’s undergraduate students within the three systems of public higher education were enrolled in community colleges, 26 percent in CSU, and 19 percent in UC. By 2023 the proportion of undergraduate students enrolled in community colleges had risen to about 75 percent, with the remaining 16 percent attending CSU and 9 percent attending UC.

The Master Plan’s vision for expanding the role of community colleges requires that CSU and UC reserve enough space to receive transfer students from community colleges. When the Master Plan was published, the ratio of CSU’s and UC’s lower‑division students to upper‑division students was about even. The Master Plan recommended that this ratio shift so that 40 percent of CSU’s and UC’s undergraduate populations were lower‑division students and 60 percent were upper‑division students—essentially reserving additional upper‑division space for incoming transfer students. In 1991 the Legislature established this same ratio in state law, as the text box shows. That legislation contained several other key statements of intent to guide the implementation of the transfer system. For example, the legislation states that the transfer system should ensure the successful transfer of students to CSU or UC, including to the campus and major of their choice, if the students’ academic performance is satisfactory. It also states that CSU and UC should prioritize the admission and enrollment of CCC students who have met transfer requirements above those students entering at the freshman or sophomore levels.

State Law Requires CSU and UC to Reserve Space for Transfer Students

“Both UC and CSU shall have as a basic enrollment policy the maintenance of upper division enrollment, which are students who have attained upper division status, at 60 percent of total undergraduate enrollment. This goal shall be met through programs aimed at increasing the numbers of qualified transfer students from the community colleges without denying eligible freshmen applicants.” [Emphasis added]

“The governing board of each segment shall ensure that individual university and college campus enrollment plans include adequate upper division places for community college transfer students in all undergraduate colleges or schools, and that each undergraduate college or school on each campus participates in developing articulation and transfer agreement programs with community colleges. The governing boards shall meet this goal within their respective general statewide planning framework used to attain and maintain the state’s goal of a 60/40 ratio of upper to lower division students, their segmental enrollment planning processes, and campus planning regarding program balance, educational quality, and other relevant goals.” [Emphasis added]

Source: Education Code section 66730.

Both the statute we quote in the text box and the related Master Plan recommendation envision the 60 percent upper‑division metric as a goal for ensuring that adequate numbers of community college transfer students can enroll at CSU and UC. However, the goal relates more directly to students’ upper‑division status than it does to their transfer status. For that reason, UC has adopted a related goal that is more specific to transfer student enrollment: its goal is to enroll two incoming resident freshmen students for every one incoming resident transfer student, which it refers to as the two‑to‑one ratio. In other words, if one assumes that it takes four years to earn a bachelor’s degree, the 60 percent upper‑division metric in state law generally equates to the enrollment of two freshmen for every one transfer student—or roughly one‑third of new students would enter as transfers. We refer to this one‑third ratio throughout our report as the transfer representation goal.2

The community college transfer process can create educational opportunities for a more diverse array of California’s students. Many sources show that students of certain racial groups and socioeconomic backgrounds are underrepresented among California’s college graduates. For instance, although the percentage of Californians with bachelor’s degrees has increased for all racial groups since 2010, disparities persist for Black or African American and Hispanic or Latino students. The transfer process can play a crucial role in addressing such disparities because students from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups have historically been more likely to start their higher education journey at a community college than at CSU or UC.

Community colleges may offer increased access to higher education for first‑generation college students and college students from low‑income households. In addition to having lower tuition costs than CSU or UC, community colleges have significantly more campuses statewide. Thus, students may not need to relocate to enroll in community college, reducing their housing and relocation costs. Community colleges may also allow students to have a more flexible class schedule if they need to work or care for family members.

Efforts to Improve the Transfer Process

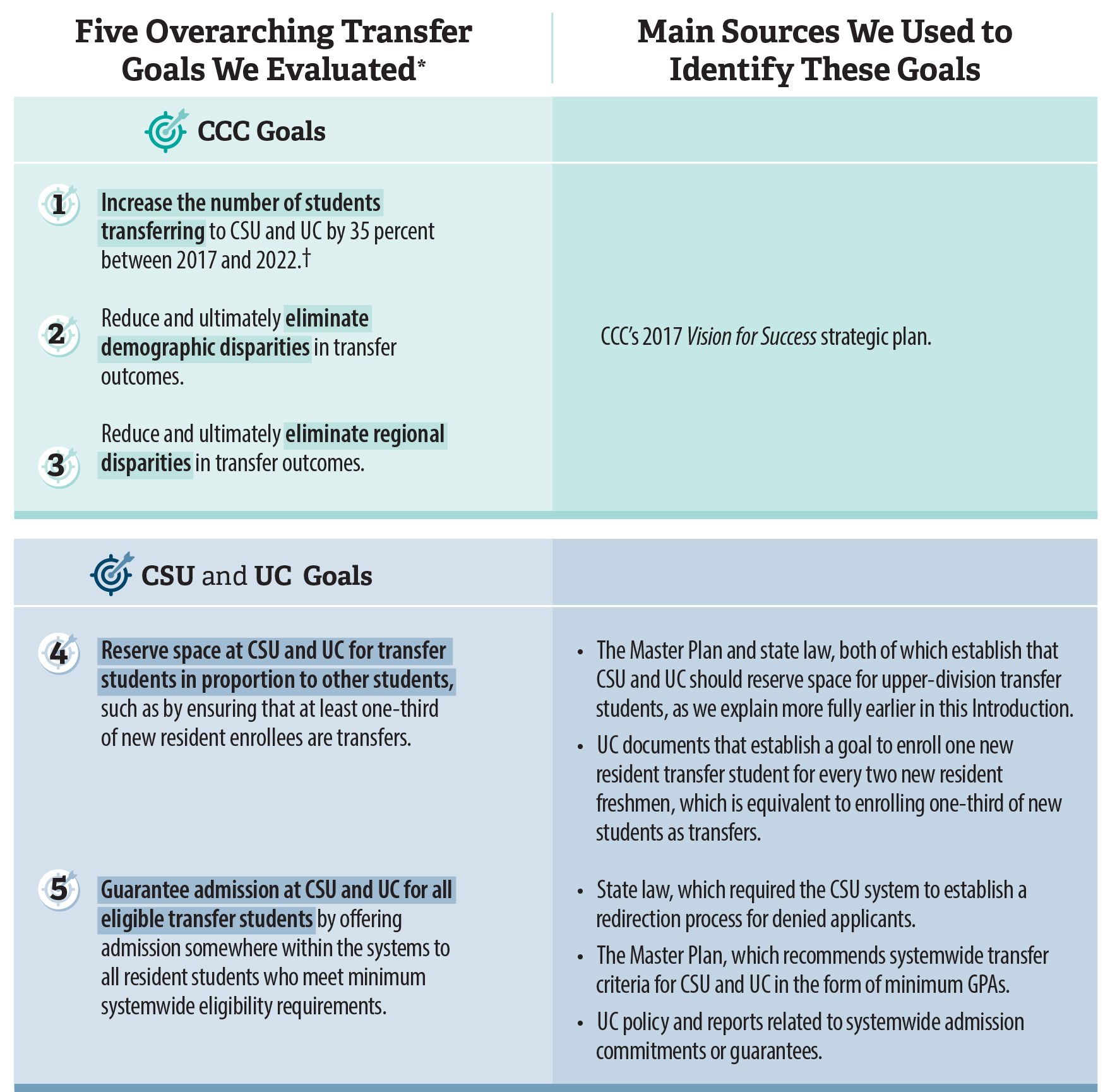

The Legislature and the three public higher education systems have undertaken efforts in recent years to improve the community college transfer process, including by setting key goals for improvement. Figure 2 depicts five overarching goals that we analyze in Chapter 1. State law and the three systems have also established many other requirements and goals, some of which we discuss in Chapter 2 and Chapter 3.

Figure 2

We Evaluated Key Goals Related to Transfer

Source: Analysis of state law, the Master Plan, key documents from the three systems, and related criteria.

* We selected these five goals so we could assess the transfer system as a whole during our audit period, even though the systems have each established additional relevant goals. Further, each system did not adopt each of these goals. For example, CCC set a goal to increase the number of transfers by 35 percent, but CSU and UC did not formally agree to this goal.

† Although CCC had not established a specific goal during our audit period related to students’ rate of successful transfer, we also evaluated transfer rates, as we explain in Chapter 1.

Figure 2 is table that lists the five overarching goals related to transfer that we evaluated. The table has two columns: the first lists the goals we evaluated, and the second provides the sources we used to identify those goals. The first three goals relate to California Community Colleges and originate from the system’s 2017 Vision for Success strategic plan. The first goal is to increase the number of students transferring to the CSU and UC systems by 35 percent over five years, and the second and third goals are to reduce and ultimately eliminate demographic disparities and regional disparities in transfer outcomes. The fourth and fifth goals, which relate to the CSU and UC systems, are to reserve space at these systems for transfer students in proportion to other students, and to guarantee admission at CSU and UC for all eligible transfer students. The main sources we used to identify these CSU and UC goals include the Master Plan, state law, and UC documents.

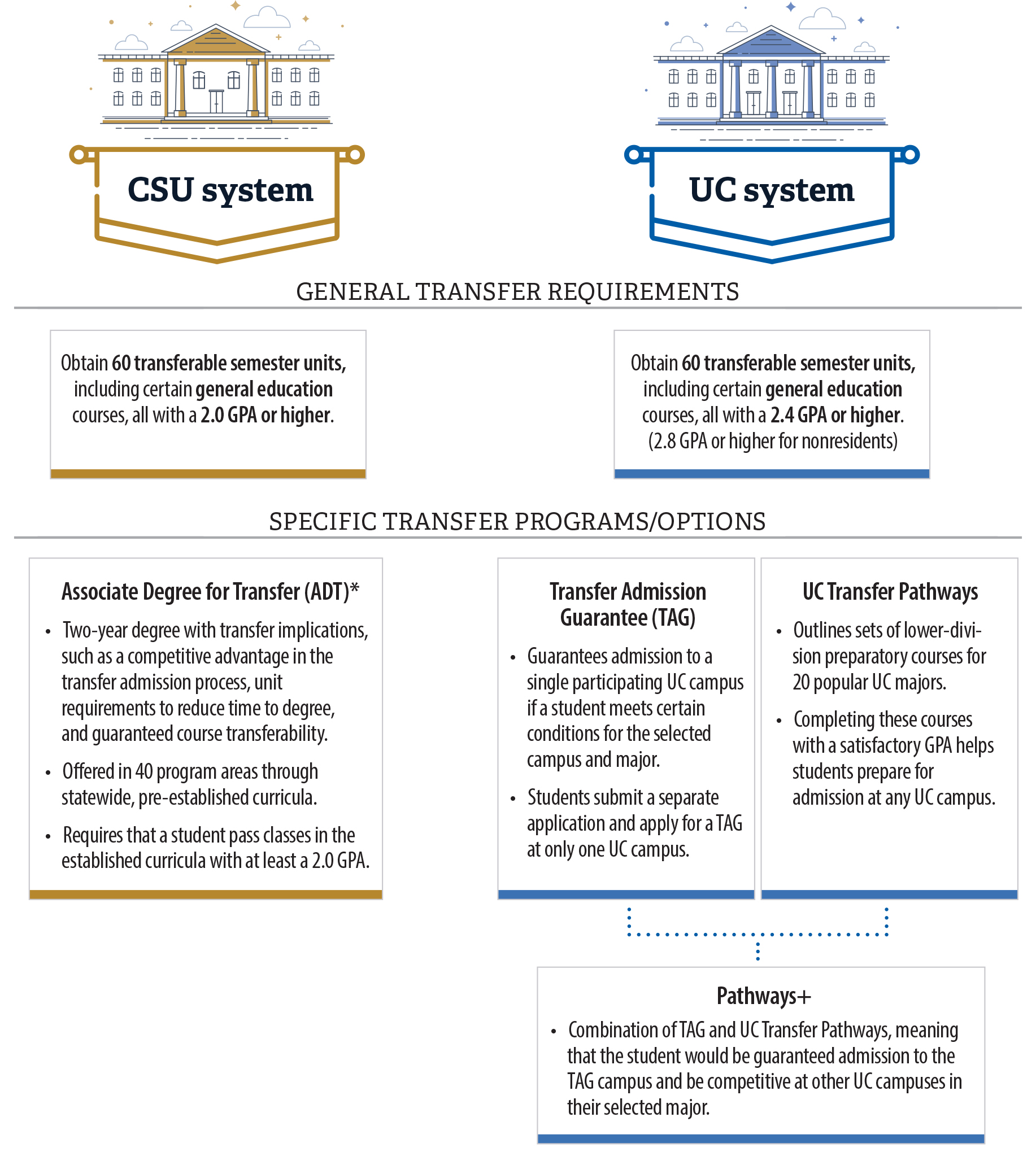

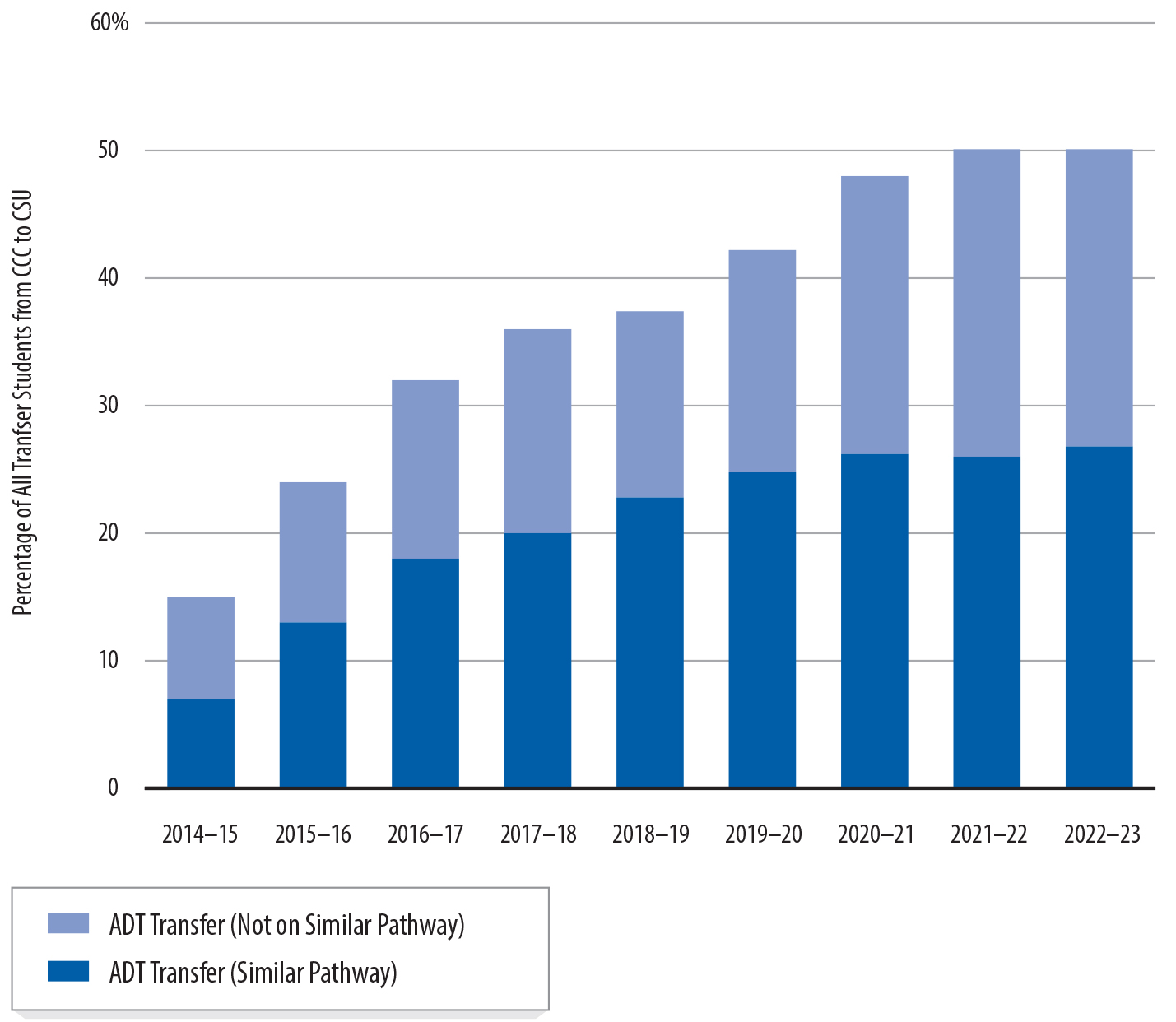

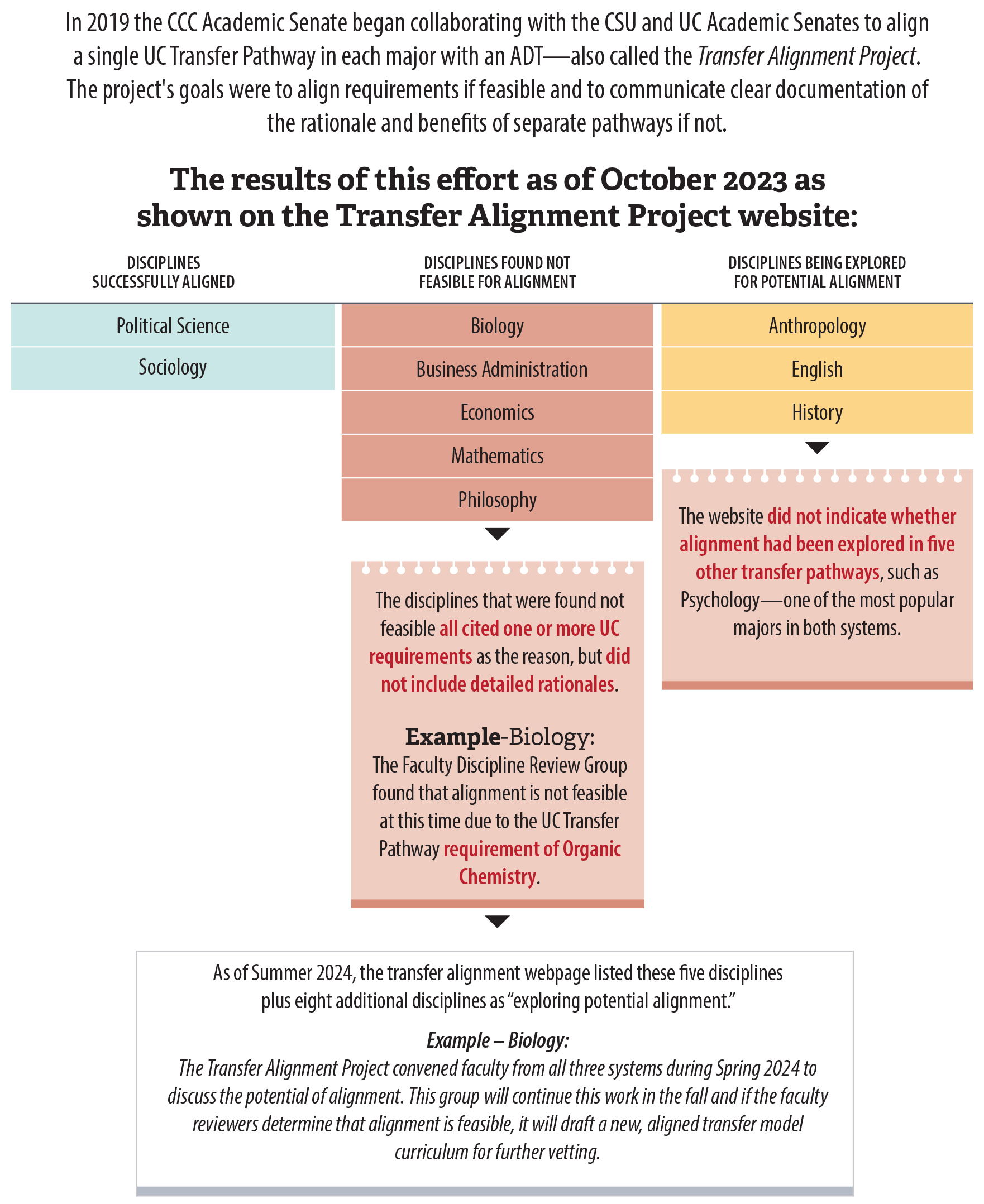

One of the most significant changes to the transfer process in the last two decades was the introduction of the Associate Degree for Transfer (ADT), which Senate Bill 1440 (Chapter 428, Statutes of 2010) established in 2010 and Senate Bill 440 (Chapter 720, Statutes of 2013) bolstered in 2013. Figure 3 describes the ADT, which consists of a maximum of 60 semester units of general education and major preparation requirements that prepare students to enter CSU at the upper‑division level. In addition, Assembly Bill 928 (Chapter 566, Statutes of 2021) established an intersegmental committee whose responsibilities include ensuring that the ADT becomes the primary transfer pathway between the CCC system and campuses in the CSU and UC systems. Assembly Bill 1291 (Chapter 683, Statutes of 2023), signed into law in 2023, establishes a pilot program that will expand the ADT to campuses and majors within the UC system, beginning in academic year 2026–27 with the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). UC has also introduced other options to attempt to streamline the transfer process, such as the Transfer Admission Guarantee (TAG) and UC Transfer Pathways. We discuss these two options and the ADT in more detail in Chapter 2.

Figure 3

Community College Students Have Multiple Options to Meet CSU and UC Transfer Requirements

Source: Analysis of state law, CSU and UC systemwide requirements and transfer programs, and public reports.

Note: We do not include in this graphic the CSU or UC dual admission programs that we discuss in Chapter 3, because those programs are still relatively new.

* State law establishes a pilot program to expand the ADT to some campuses and majors within the UC system, beginning with at least eight majors at UCLA in the 2026–27 academic year.

Figure 3 provides an overview of transfer requirements and transfer options for the CSU and UC systems. Both systems generally require that a transfer applicant obtain 60 transferable semester units, including certain general education courses, and CSU requires a 2.0 GPA or higher for transfer whereas UC requires a 2.4 GPA or higher. In terms of specific transfer programs or options, the primary transfer program for the CSU system is the Associate Degree for Transfer, or ADT. For the UC system, there are two main transfer options: the Transfer Admission Guarantee, known as TAG, and the UC Transfer Pathways. UC considers a program called “Pathways-plus” to be a third option, and it is a combination of TAG and UC Transfer Pathways. The figure provides additional details for each of these specific programs or options, such as that the ADT is a two-year degree that can reduce transfer students’ time to earn a bachelor’s degree and guarantee course transferability.

Several other recent laws have also affected the transfer process. For example, legislation enacted in 2017 and 2022 established a framework to increase the probability that community college students will enter and complete transfer‑level coursework in English and mathematics during their first year. Legislation enacted in 2021 required CCC to adopt a common course‑numbering system across all of its colleges and, in February 2024, a task force issued its final report about the design and implementation of this effort. Another 2021 state law assigned a committee to establish a singular lower‑division general education pathway known as the California General Education Transfer Curriculum (Cal‑GETC) and separately mandated that transfer‑intending students be placed onto an ADT pathway if such a pathway exists for their intended major. Because this law is recent, its impact has not yet been fully realized. For example, Cal‑GETC will not take effect until the 2025–26 academic year.

In June 2023, the Joint Legislative Audit Committee directed our office to review the higher education systems’ efforts to improve the percentage of community college students who transfer to CSU and UC. To conduct our review, we judgmentally selected campuses to represent all three higher education systems and the State’s diverse geography and student demographics. Those campuses were the following: Clovis Community College (Clovis); Diablo Valley College (Diablo Valley); Lassen Community College (Lassen); Santa Ana College (Santa Ana); Victor Valley College (Victor Valley); San Diego State University (San Diego State); California State University, Stanislaus (Stanislaus State); University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley); and University of California, Santa Barbara (UC Santa Barbara).

Chapter 1

The State’s Three Higher Education Systems Have Struggled to Meet Some Key Goals Related to Student Transfers

Chapter Summary

- Only about 21 percent of community college students who began college from 2017 to 2019 and intended to transfer did so within four years, and transfer rates were even lower for students from certain demographic groups and regions of the State. Of the 745,000 transfer‑intending students who did not transfer within four years, about 96 percent did not apply to CSU or UC. Further, most of those students who did not apply—61 percent—had earned 30 or fewer units.

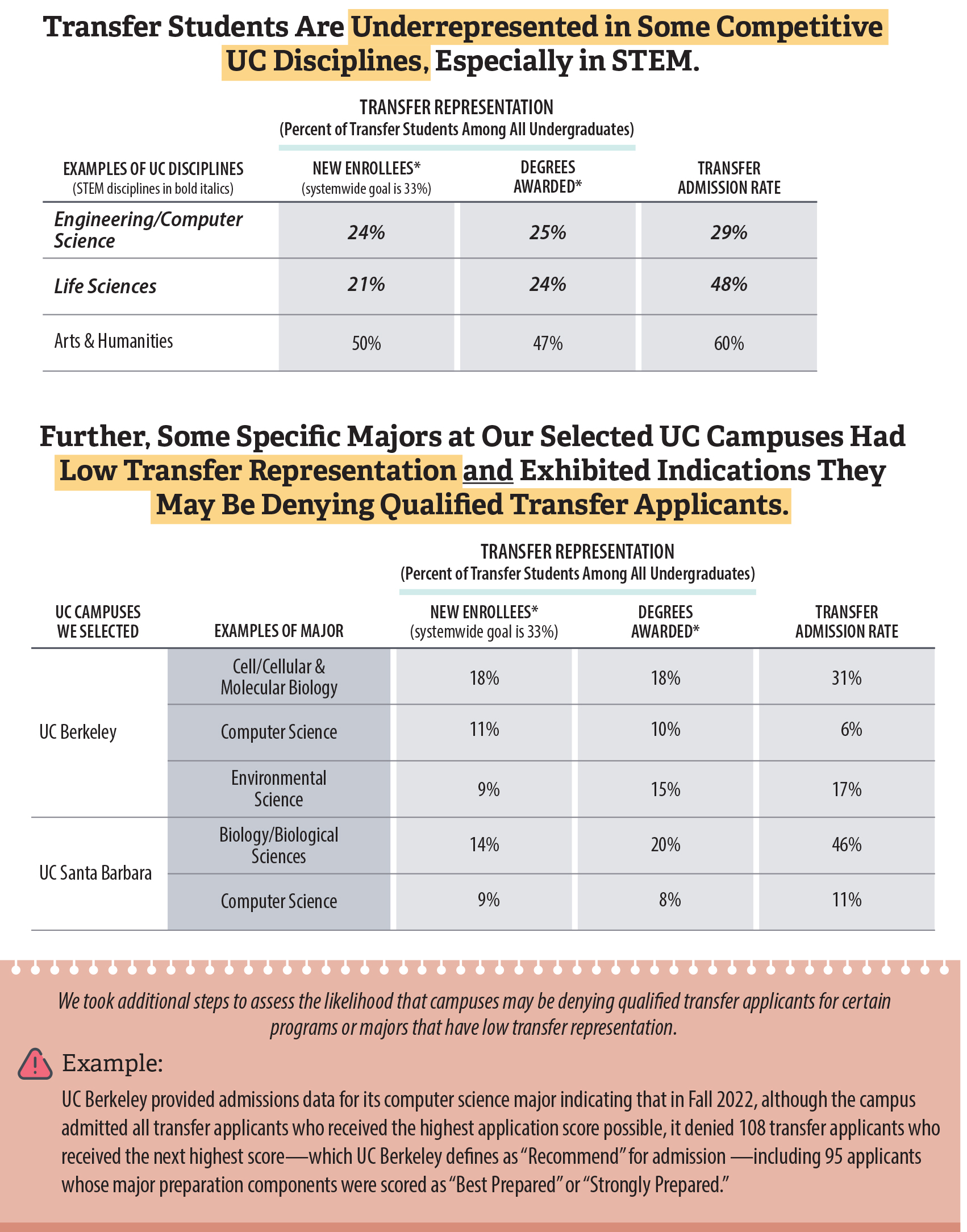

- More than 90 percent of CSU transfer applicants and more than 75 percent of UC transfer applicants gained admission to at least one campus in those systems. However, transfer applicants’ access to competitive campuses and majors—such as California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo (Cal Poly San Luis Obispo); UC Berkeley; and science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) majors across several campuses—was more limited than their access to other campuses and majors.

- Systemwide, both CSU and UC met the key transfer representation goal of enrolling at least one‑third of their new students through transfer. However, certain campuses and majors within each of the systems did not meet this goal. CSU and UC could help ensure that transfer students have adequate access to their preferred campuses and majors by monitoring campuses’ and majors’ efforts to enroll transfer students and following up with those campuses that have low transfer representation and may be denying qualified transfer applicants.

CCC Has Taken Steps to Facilitate Student Transfers to CSU and UC, but the System Is Not Yet Meeting Certain Critical Goals

Many students enroll in community college intending to transfer, yet the percentage who successfully do so has remained low—our analysis shows that about 21 percent of transfer‑intending students transferred within four years of enrolling in a community college, and less than 30 percent transferred within six years. The possible causes for low transfer rates include underlying barriers such as financial insecurity, family responsibilities, and an inability to relocate. However, students may also face educational barriers related to accessing community college courses they need to transfer or understanding complex transfer requirements. Although CCC has taken steps to facilitate transfer and address some of these barriers, opportunities still exist for CCC to monitor and increase transfer rates.

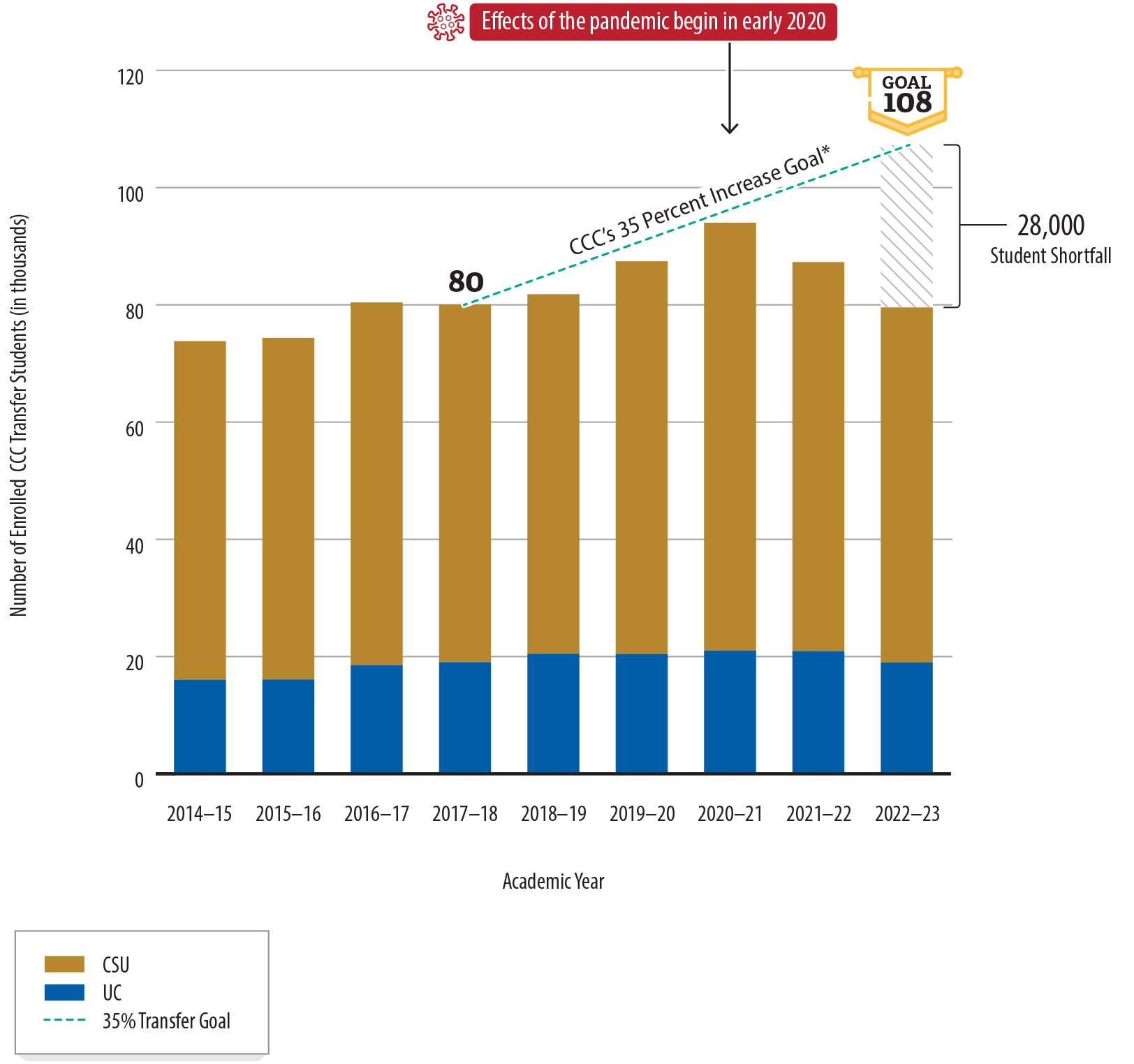

The Number of Students Transferring to CSU and UC Has Increased but Still Falls Short of CCC’s Goal

In its 2017 Vision for Success strategic plan, CCC adopted a goal to increase the number of its students who transfer each year to CSU or UC by 35 percent over five years—from about 80,000 students to about 108,000 students. Figure 4 shows that CCC was making progress toward that goal before the effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic (pandemic) began in 2020. At that time, the number of CCC students who transferred to CSU or UC started to decline.

Figure 4

CCC Was Making Progress Toward Its Transfer Goal, but the Number of Transfers Sharply Declined After the Pandemic

Source: CSU and UC internal application and enrollment data from 2018 through 2023, CSU and UC publicly reported enrollment data from 2014 through 2018, and CCC’s 2017 Vision for Success.

* Although CCC’s Vision for Success does not clearly articulate a baseline for this goal, we display the initial baseline for CCC’s goal to increase transfers by 35 percent as 80,000 transfers based on publicly reported CSU and UC data for academic year 2017–18.

Figure 4 is a vertical stacked bar chart showing that CCC was making progress toward its goal to increase the number of transfers to CSU and UC by 35 percent over five years—or from about 80,000 transfers to about 108,000 transfers by the 2022-23 academic year. However, the number of students transferring to CSU or UC declined after the effects of the pandemic began in early 2020. Each vertical bar represents the combined number of enrolled CCC students at CSU or UC, with different colors for transfers to CSU and transfers to UC. The horizontal axis represents academic years, starting with 2014-15 and ending with 2022-23. Academic year 2017-18 includes the baseline figure of 80,000 transfer students. That number steadily increased through the 2020-21 academic year, but declined after that, resulting in a 28,000-student shortfall from CCC’s goal of 108,000 transfers by academic year 2022-23.

Beyond the overall number of students who transfer to CSU and UC, another measure of the effectiveness of the community college transfer process is the rate of successful transfer among all CCC students who express a goal of transferring or who exhibit course‑taking behavior consistent with the intent to transfer (transfer‑intending students). When transfer rates are low, it means that fewer CCC students successfully obtain bachelor’s degrees and benefit from the associated opportunities, such as increased earnings. Despite the importance of measuring transfer rates, the CCC system had not established a formal goal for this metric at the time of our audit. However, the CCC Chancellor’s Office has published on its website these types of transfer rates statewide and for individual community colleges. It and other research entities have found that only a fraction of community college students who intend to transfer are able to do so successfully.

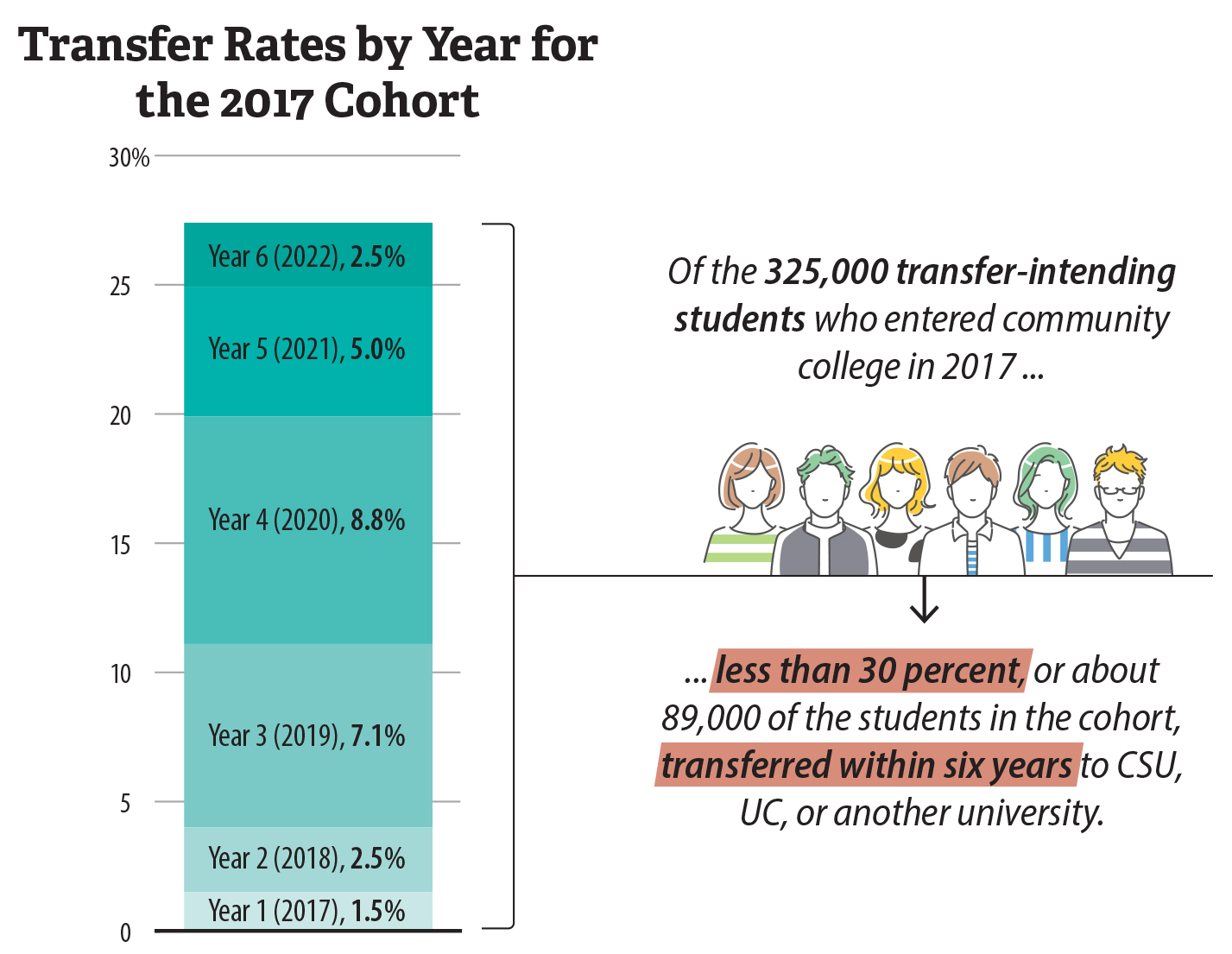

When we analyzed data from the State’s three higher education systems, we found that less than 30 percent of the 325,000 transfer‑intending students who enrolled in community college in 2017 transferred within six years, as Figure 5 shows. To calculate this transfer rate, we identified the cohort of students who entered community college in 2017. We then limited this cohort to transfer‑intending students and measured how many transferred within the six years. In addition to the six‑year cohort transfer rate for students who entered community college in 2017, we also calculated transfer rates for four‑year cohorts—displayed in Table A.1 of Appendix A—to provide comparisons across time and to include students who entered college more recently.

Figure 5

Most Transfer‑Intending Students Did Not Transfer Within Six Years

Source: CCC student and course data and CSU and UC admissions data.

Note: The transfer rates above are based on our matches of CCC students to CSU and UC admissions data and National Student Clearinghouse data provided by the CCC Chancellor’s Office. A small number of CCC students may have transferred to CSU, UC, or other universities whom we were unable to identify because of limitations in the data. For more information, refer to the Scope and Methodology section in Appendix D.

Figure 5 is a graphic showing transfer rates by year for the 2017 cohort of transfer-intending community college students. The graphic includes a single vertical bar in which transfer rates are stacked by year for each of the six years beginning with 2017. For example, 8.8 percent of cohort students transferred in Year 4, which was 2020—the most common of the six years for students to have transferred. The figure explains that of the 325,000 transfer-intending students who entered community college in 2017, less than 30 percent, or about 89,000 of the students in the cohort, transferred within six years to CSU, UC, or another university.

The four‑year transfer rates we calculated remained relatively consistent—about 20 percent across several different student cohorts, as Table A.1 in Appendix A shows. For example, the transfer rate increased by less than 1 percent from the 2017 cohort to the 2019 cohort, although the total number of transfer‑intending students in the cohorts declined by about 6 percent during the same period. The transfer rates we calculated also generally align with other entities’ findings, even though their methodologies may have differed. For instance, the Public Policy Institute of California published a report in August 2023 that stated that about 19 percent of transfer‑intending students transfer within four years of their initial community college enrollment.

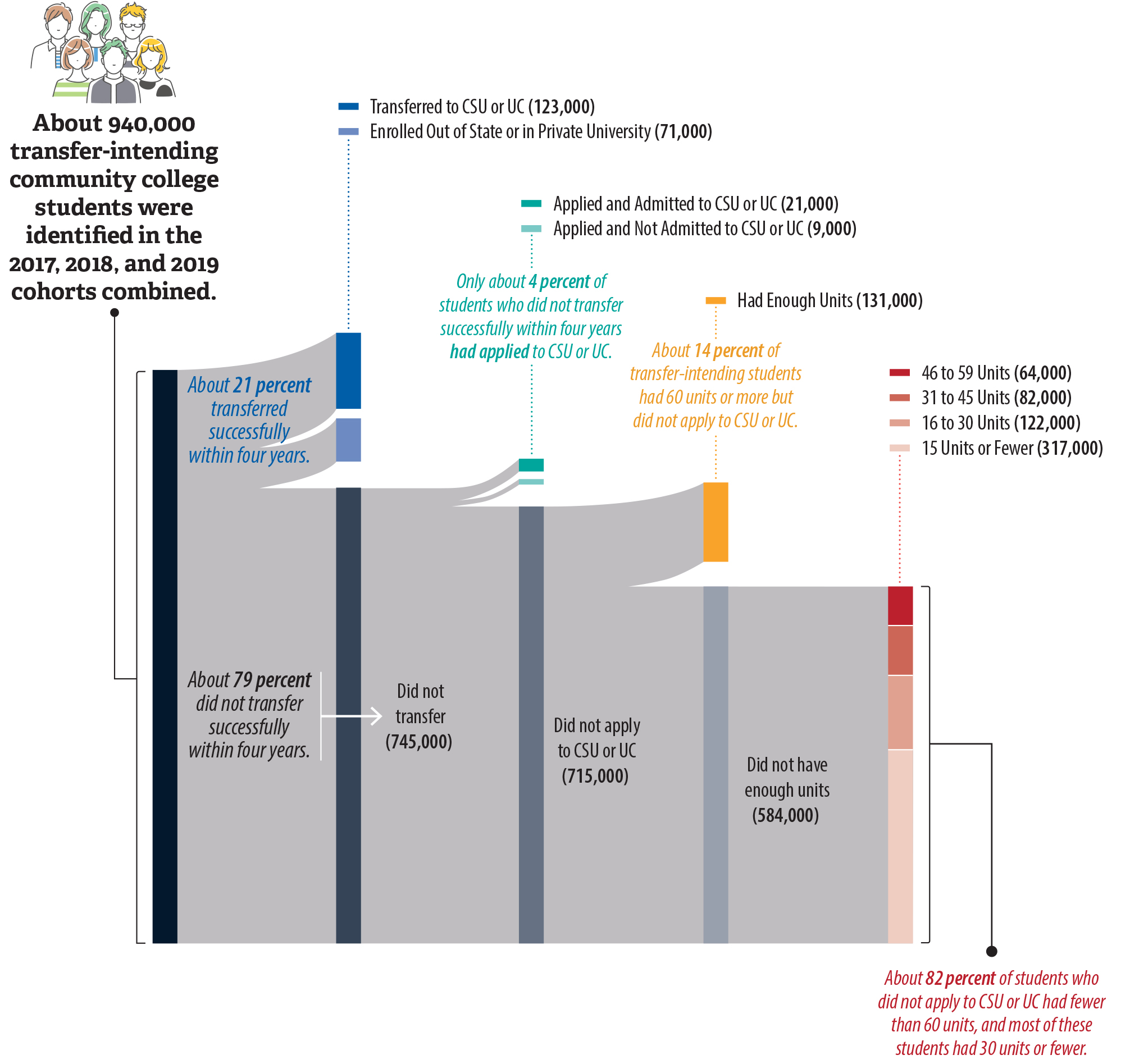

Most transfer‑intending students who did not successfully transfer within four years never applied to CSU or UC, likely in large part because they had not earned enough units of credit. Figure 6 depicts the transfer outcomes for students in all three of the four‑year cohorts that we analyzed, and it illustrates that most transfer‑intending students who did not apply to CSU or UC earned fewer than 60 units of community college credit. In fact, slightly more than half of those students earned 15 units or fewer. Many causes could explain this trend, including students not completing courses or not returning after the first term.3

Figure 6

Most Students Who Did Not Transfer Within Four Years of Enrollment Had Not Applied to CSU or UC, and Many Had Earned Few Units

Source: Analysis of CCC, CSU, and UC data, including National Student Clearinghouse information for students who transferred to universities other than CSU and UC.

Notes: Individual numbers are rounded and may not align precisely with the totals presented.

The transfer rates above are based on our matches of CCC students to CSU and UC admissions data and National Student Clearinghouse data provided by the CCC Chancellor’s Office. A small number of CCC students may have transferred to CSU, UC, or other universities whom we were unable to identify because of limitations in the data. For more information, refer to the Scope and Methodology section in Appendix D.

The National Student Clearinghouse data we analyzed, which we relied upon for information about students who transferred to universities other than CSU and UC, did not include information about students’ applications for transfer. Therefore, the portion of this graphic related to applications and admissions includes information only for CSU and UC.

Figure 6 is a Sankey diagram that moves from left to right to show that most students who did not transfer within four years of enrollment had not applied to CSU or UC and had earned few units of credit. On the left, the chart begins with 940,000 transfer-intending community college students among the 2017, 2018, and 2019 cohorts combined. The diagram then shows that about 21 percent of this combined cohort transferred successfully within four years to CSU, UC, or another university, meaning that 79 percent did not transfer within four years. Of the 79 percent or 745,000 students who did not transfer, only about 4 percent had applied to CSU or UC. The final stage of the diagram depicts that of those students who did not apply to CSU or UC, the vast majority—about 82 percent or 584,000 students—had fewer than 60 units, which implies that they did not have enough units to transfer. In fact, most of these students with fewer than 60 units had 30 units or fewer.

Other students in the cohorts we analyzed did not apply to CSU or UC even though they may have been transfer‑ready. For instance, about 14 percent of transfer‑intending students—131,000 students—did not apply for transfer within four years despite earning 60 units or more of community college credit, as Figure 6 shows.4 The text box includes some of the possible reasons that these students did not apply to CSU or UC. Similarly, the Research and Planning Group for California Community Colleges (RP Group) reported in May 2020 that thousands of students had made significant progress toward transfer but found themselves stuck in the system or abandoned their goals. In addition to identifying other areas of opportunity, the RP Group recommended that community colleges begin by quantifying the transfer‑intending populations on their campuses and proactively reaching out to help students who have made considerable progress toward transfer.

Possible Reasons That Students With 60 or More Units Did Not Apply to CSU or UC

- They delayed transferring until a later time, perhaps because of the effects of the pandemic.

- Even though they had enough overall units, they had not met the course or GPA requirements for a particular CSU or UC campus or major.

- They faced other barriers, such as financial constraints, family responsibilities, or difficulty navigating the application process.

- They entered the work force having decided that they did not want to transfer.

Source: Interviews with CCC Chancellor’s Office and community college officials corroborated by public reports and research.

Other sources and best practices also identify ways in which colleges could monitor students’ progress toward transfer and provide targeted interventions, some of which we discuss in Chapter 3, to help them reach the point of applying and transferring. For example, Diablo Valley’s 2021 program review of its transfer services included a strategy to increase outreach to students enrolled in transfer‑level English and math support courses—such as through class visits to the transfer center—to reach and assist the students most at risk of not transferring. In addition, an intersegmental committee report from December 2023 recommended reengaging students who have already earned an ADT but did not apply to transfer. Nearly 16,000 students statewide across the three cohorts we measured had obtained an ADT within four years of enrollment but did not apply to CSU or UC, as we show in Table A.8 in Appendix A. A 2021 update to CCC’s Vision for Success highlighted additional examples of promising practices at specific community colleges. CCC’s assistant vice chancellor for data, visualization, and research acknowledged that some community colleges have already developed practices for increasing transfer rates and told us that determining the success of these practices would be a helpful first step that could then allow the Chancellor’s Office to provide useful guidance to all colleges.

As the text box shows, underlying low transfer rates are several fundamental barriers that transfer‑intending students face. Although some barriers we detail in the text box involve factors largely outside of the higher education systems’ control, the systems can still take important steps to facilitate and simplify the transfer process, as we discuss throughout this report.

Students May Face Several Barriers to Successfully Transferring

Key institutional barriers that are primarily a CCC responsibility:

- Lack of timely and accurate information about the transfer process.

- Difficulty for students to access and successfully complete courses needed for transfer.

Key institutional barriers that are primarily a CSU and UC responsibility:

- Complex transfer requirements that are difficult for students to understand and fulfill.

- Limited capacity to accommodate students at some campuses and majors.

Key personal barriers that require support from the three systems:

- Inability to address basic needs, such as financial security or family responsibilities, making it difficult to prioritize the effort to transfer.

- Inability to relocate or access universities outside of the local community.

Source: Analysis of public research and reports, and interviews with CCC Chancellor’s Office and community college officials.

Students in Some Demographic Groups Are Significantly More Likely to Transfer Than Students in Others

State law and CCC have established that the system should make efforts to help students from historically underrepresented groups transfer. For example, state law includes requirements for CCC to work toward the goal of eliminating disparities in outcomes between certain demographic groups (achievement gaps), including those related to transfer, as a condition of receipt of certain state funds. Similarly, CCC established a 10‑year goal in its 2017 Vision for Success to reduce and ultimately close achievement gaps across a range of outcomes, such as transferring successfully.

Although some transfer‑related achievement gaps have narrowed in recent years, significant disparities still exist. For example, the four‑year transfer rate for Hispanic or Latino students in the 2019 cohort was about 15 percent, compared to the rate of nearly 21 percent for all students. Table A.5 in Appendix A provides additional details on transfer outcomes by demographic group for the student cohorts we analyzed. In general, the disparities between the overall makeup of our cohorts and the students who ultimately transferred are wider at UC than at CSU, especially for Black or African American and Hispanic or Latino students. Public data and research show that in recent years, both systems have increased their shares of community college transfer enrollees who are from certain underrepresented groups, particularly Hispanic or Latino students. Nevertheless, the remaining gaps mean that transfer‑intending students from some demographic groups are less likely to achieve their transfer goals.

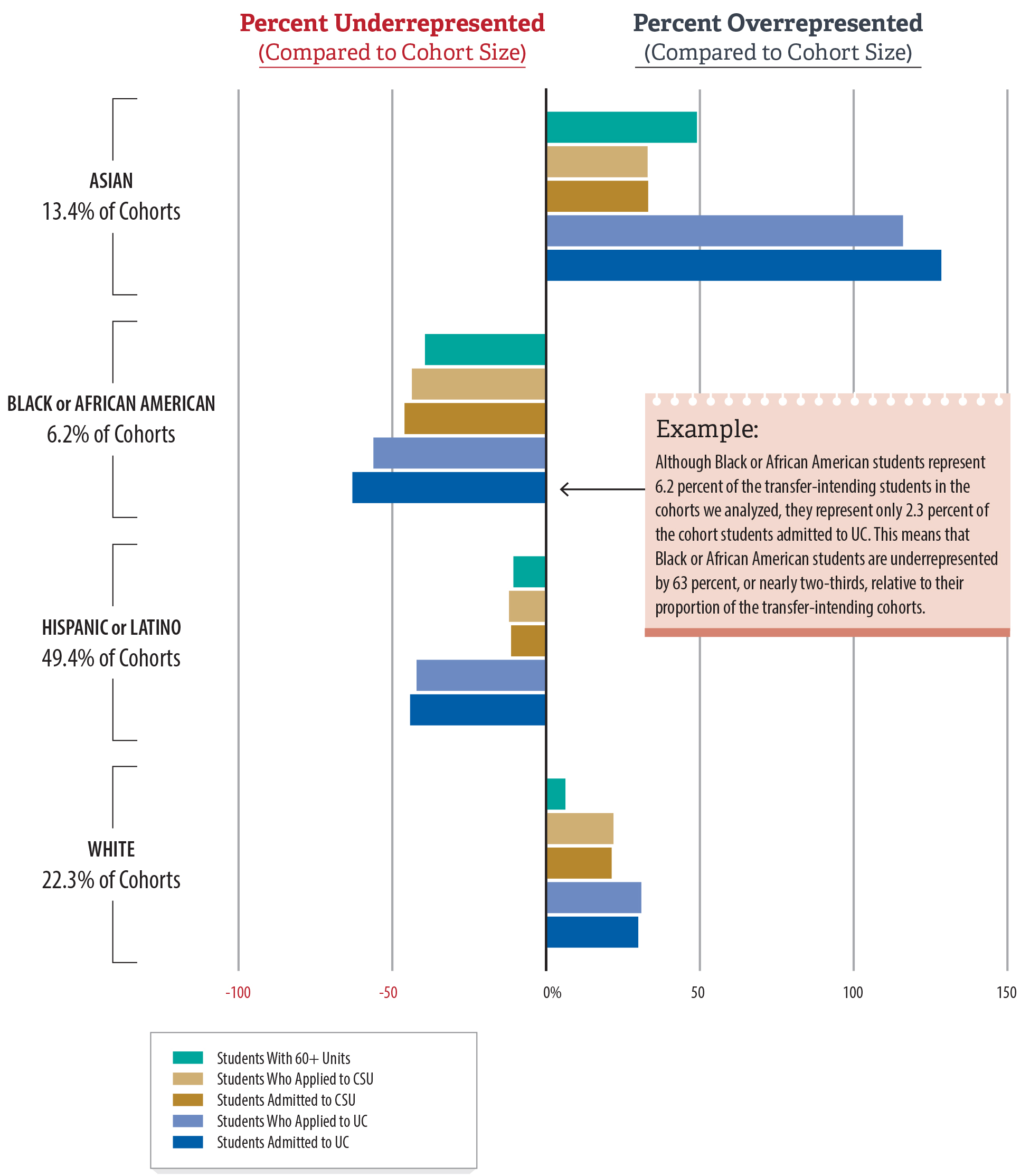

Understanding the stages of the transfer process that contribute to demographic disparities can reveal their possible causes and inform more targeted interventions. We found that racial or ethnic groups’ representation changed at several stages in the transfer process for the 2017 through 2019 cohorts, including at or before the transfer application stage, as Figure 7 shows. For example, Hispanic or Latino students comprise less of the population who applied to UC, which is a large part of why they also make up less of the population who were admitted to UC. Similarly, Black or African American students comprise about 6 percent of transfer‑intending students in the cohorts but only about 3 percent of cohort applicants to CSU and UC. In Chapter 3, we discuss approaches each system could take to better identify and support transfer‑intending community college students, including students from underrepresented groups.

Figure 7

Not All Student Groups Are Represented Equally in Transfer Preparedness and Admissions

Source: Analysis of a combination of the 2017, 2018, and 2019 student cohorts we created based on CCC, CSU, and UC data.

Notes: The outcomes above—such as whether students obtained 60 or more units, applied to transfer, and were admitted—are based on four years of data beginning with the year a student entered into the community college system. We depict only the four largest racial or ethnic groups in the cohorts.

The application and admission rates above are based on our matches of CCC students to CSU and UC admissions data. A small number of CCC students may have applied or been admitted to CSU or UC whom we were unable to identify because of limitations in the data. For more information, refer to the Scope and Methodology section in Appendix D.

Figure 7 is a clustered horizontal bar chart depicting the four largest racial or ethnic student groups’ representation at different stages of the transfer process for the combined 2017, 2018, and 2019 transfer-intending cohorts. For each group—Asian students, Black or African American students, Hispanic or Latino students, and white students—five bars signify the group’s representation among students at different stages of the transfer process. These stages consist of students with 60 or more units, students who applied to CSU, students who were admitted by CSU, students who applied to UC, and students who were admitted by UC. For each group, bars to the left of the central axis represent an underrepresentation compared to the cohort of transfer-intending students, and bars to the right represent an overrepresentation of the group. In general, the chart shows that Asian and white students were overrepresented in these five transfer stages compared to their share of the initial cohort, whereas Black or African American and Hispanic or Latino students were underrepresented. The chart also reveals that racial or ethnic groups’ representation changed at different stages, including at or before the transfer application stage.

Some Community Colleges and Regions Have Significantly Lower Transfer Rates Than Others

As an example of how transfer rates vary among community colleges, for the 2017 through 2019 cohorts we reviewed, the 10 colleges with the highest four‑year transfer rates averaged rates of about 33 percent, whereas the 10 colleges with the lowest rates averaged about 10 percent. Table A.2 in Appendix A shows transfer rates for those colleges with the highest and lowest rates and for the five colleges we selected for this audit. Transfer rates also varied by community college district, many of which contain only one college. The differences in transfer rates mean that transfer‑intending students at certain community colleges are significantly more likely to transfer than those at other colleges.

Location is one cause of college‑level differences in transfer rates. As Table A.6 in Appendix A shows, our review found that community colleges in the Bay Area, San Diego, and South Central regions had higher transfer rates than colleges located in the Central Valley, Inland Empire, and Northern regions of the State. One factor contributing to this difference may be the distances between community colleges and CSU and UC campuses in those regions. Students are more likely to transfer to a nearby university for a variety of reasons, including challenges associated with relocating.

The executive vice president of student and administrative services at Lassen—a college in rural Northern California—stated that proximity is a major barrier for its students who want to transfer to CSU or UC. The nearest CSU or UC campus to Lassen is Chico State University, which is more than a two‑hour drive. In fact, in the cohorts we analyzed, nearly 76 percent of the Lassen students who successfully transferred did so to an out‑of‑state institution. A number of these students may have transferred to the University of Nevada, Reno, because it is closer to Lassen than any CSU or UC campus.

Similarly, Victor Valley’s dean of student services stated that location is a significant barrier to transfer for the college’s students. For example, its transfer‑intending students face a difficult commute through a mountain pass to reach the nearest CSU and UC campuses in San Bernardino and Riverside, and the public transportation options are limited. The dean added that the cost of living in those areas is much higher than in Victor Valley’s service area, which is a burden for most students.

Research has proposed solutions for geographic barriers to transfer. For example, the Public Policy Institute of California suggested in its August 2023 report that community colleges located far from universities should work to establish partnerships that allow students to obtain a bachelor’s degree by taking university courses at the community college. Lassen’s executive vice president of student and administrative services stated that the college has been working to develop such partnerships with CSU campuses and that the partnerships are helpful for students. However, she stated that challenges persist, such as persuading CSU faculty to relocate to establish programs at Lassen or convincing CSU campuses of the viability of alternative options that incorporate hybrid learning models. Similarly, San Diego State has an Imperial Valley branch that serves students in southeastern California who may not be able to relocate to San Diego, which is more than 100 miles away from the branch.

State law allows community college districts to establish bachelor’s degree programs as long as certain conditions are met, including that the bachelor’s degrees do not duplicate degrees that CSU and UC already offer. Expanding the ability of geographically isolated community colleges to offer bachelor’s degrees could help those colleges’ students meet their educational goals. The Public Policy Institute of California has also found that uneven outreach from four‑year institutions, especially in regions with fewer campuses, may constrain students’ awareness of potential transfer destinations, making them less likely to apply. It stated that four‑year institutions must do more to reach out to students, an approach we discuss more fully in Chapter 3.

In addition to location, other factors may contribute to differences in community colleges’ transfer rates. As we show in Figure 7, student groups are not all represented equally in terms of transfer preparedness and admissions—and community colleges serve different proportions of these student groups. Similarly, some colleges—such as Diablo Valley or Irvine Valley College—may attract students who have demonstrated strong academic performance and who wish to transfer to a nearby campus, such as UC Berkeley or the University of California, Irvine. Finally, as we discuss in Chapter 3, we identified weaknesses in some colleges’ processes for helping students transfer.

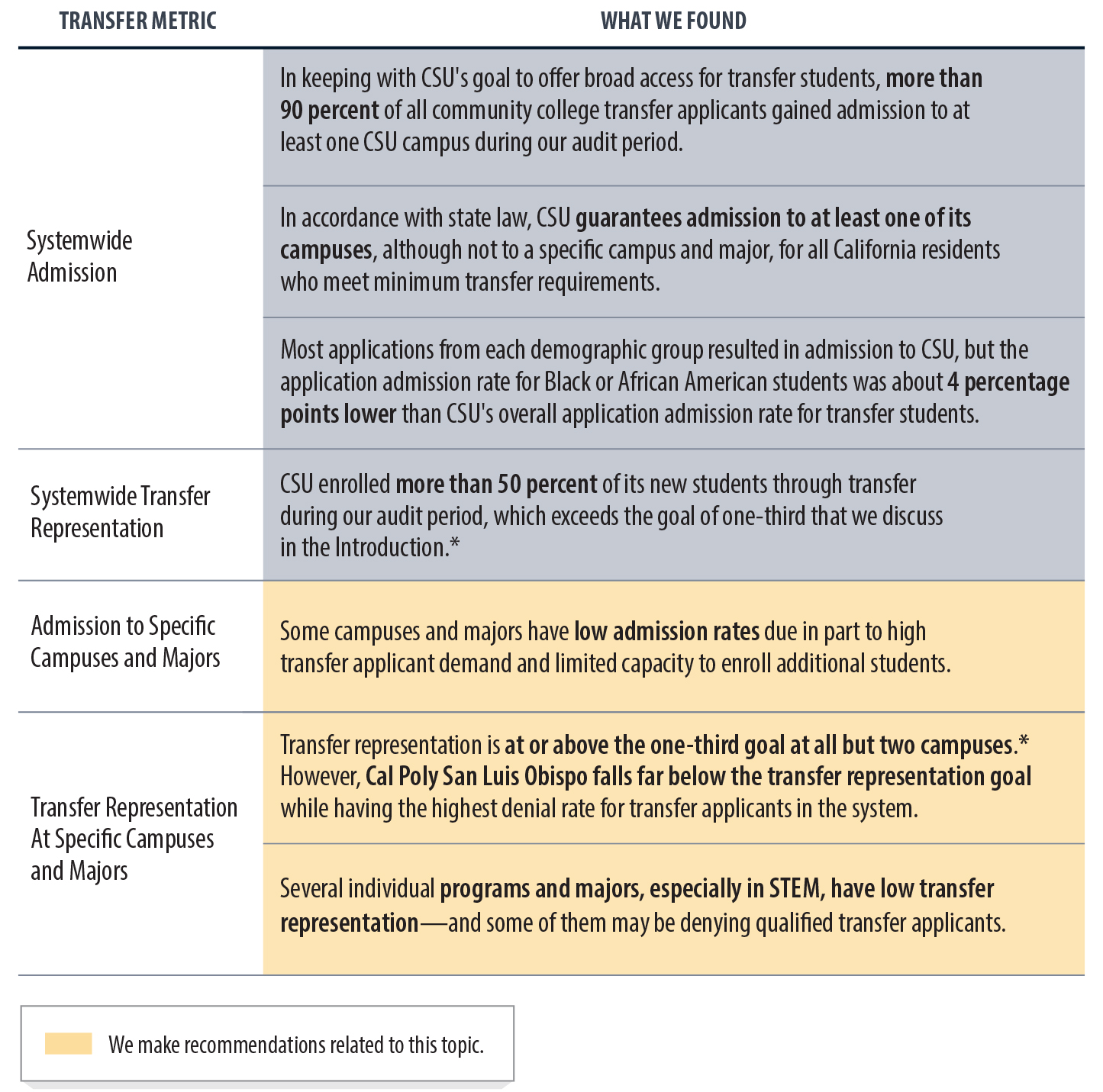

CSU Admits Nearly All Transfer Applicants but Not Always to Their Preferred Campuses and Majors

As Figure 8 demonstrates, most community college transfer students who apply to CSU gain admission to at least one campus. However, they do not necessarily gain admission to their preferred campus or major. Students may prefer a particular campus or major for a variety of reasons, including the potential future employment opportunities associated with earning a degree. They must also meet requirements specific to those campuses or majors, as we discuss in Chapter 2. By prioritizing the admission of transfer students to certain competitive campuses and majors, CSU could better ensure that these students ultimately enroll and earn degrees in their desired fields of study.

Figure 8

CSU Accommodates Many Transfer Students but Can Improve Access to Certain Campuses and Majors

Source: Analysis of state law, the Master Plan, CSU application and enrollment data, and other system documents.

* As we explain in the Introduction, we derived this goal—to enroll one‑third of new resident undergraduates through transfer—from a UC goal that is related to an upper‑division enrollment requirement for CSU and UC in state law.

Figure 8 includes analysis of four transfer metrics that we discuss in our report as they relate to CSU—systemwide admission, systemwide transfer representation, admission to specific campuses and majors, and transfer representation at specific campuses and majors. For example, with regard to systemwide admission, we found that more than 90 percent of all community college transfer applicants gained admission to at least one CSU campus during our audit period. In terms of transfer representation, the system enrolled more than 50 percent of its new resident undergraduates through transfer. However, we found that some individual campuses and majors have low admission and transfer representation rates, with Cal Poly San Luis Obispo falling far below the transfer representation goal while having the highest denial rate for transfer applicants in the system. A key at the bottom of the graphic indicates that we make recommendations related to these findings about CSU campuses and majors.

CSU Admits More Than 90 Percent of All Community College Transfer Applicants

As we note in the Introduction, one key expectation in law is that CSU is to offer admission to all eligible transfer applicants. In alignment with this goal, CSU’s overall admission rate is high: it admitted to at least one campus more than 90 percent of the nearly 500,000 CCC students who applied to transfer from academic years 2018–19 through 2022–23. Table B.1 in Appendix B shows that this systemwide admission rate remained relatively constant during our audit period. Further, as we discuss in the next section, CSU has established a process for determining applicants’ eligibility and ensuring that all eligible students have an opportunity to enroll at one of its campuses.

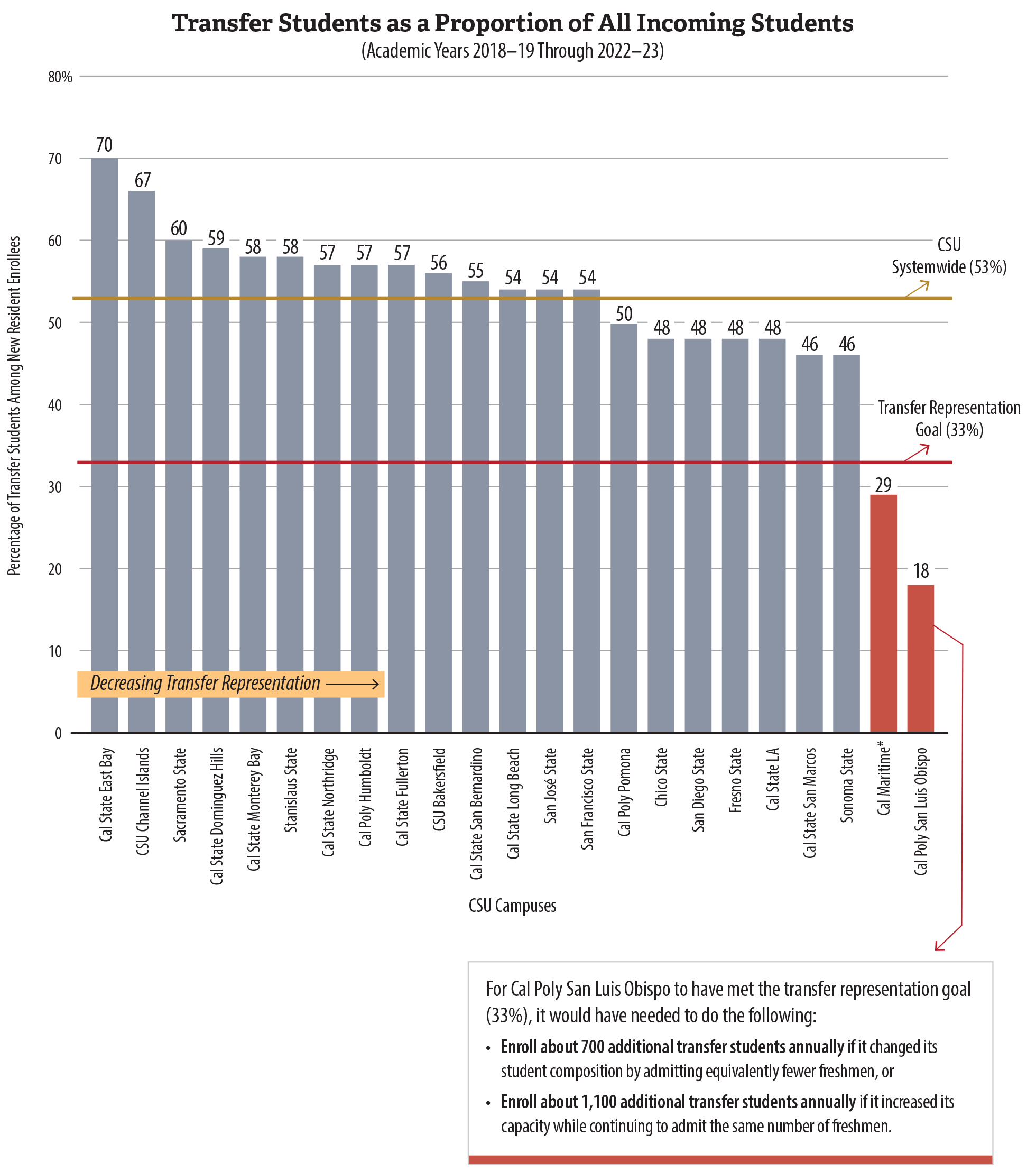

CSU also largely met another key goal to enroll a sufficient number of transfer students compared to the number of freshmen students it enrolls. Although CSU has not explicitly framed that goal in terms of enrolling at least one‑third of its students through transfer, this specific ratio aligns with the intent of both the Master Plan and state law, as we discuss in the Introduction. As Figure 9 shows, CSU enrolled far more than one‑third of its incoming students through transfer. In fact, many CSU campuses enrolled transfer students at a rate greater than one‑half of all incoming students.

Figure 9

A Large Proportion of CSU’s New Enrollees are Transfer Students, but Cal Poly San Luis Obispo Has Low Transfer Representation

Source: Analysis of CSU enrollment data from academic years 2018–19 through 2022–23.

Note: We included in these ratios all transfer students, not just those from community colleges, and we limited the ratios to California resident students because UC has used this methodology and we wanted to provide consistency between CSU and UC ratios. However, according to CSU’s public dashboards, more than 96 percent of students who transfer to CSU are California residents, and more than 93 percent of resident students who transfer to CSU originate from California community colleges.

* Cal Maritime has limited and specialized programs compared to other CSU campuses, which may affect its level of transfer representation.

Figure 9 is a bar chart consisting of 23 bars that show each CSU campus’s percentage of transfer students among its new resident enrollees, with the campuses presented from left to right in decreasing order of transfer representation. One horizontal line shows that, systemwide, CSU’s transfer representation is about 53 percent, and another shows the transfer representation goal of about 33 percent. Cal State East Bay is the CSU campus with the largest share of transfer students among incoming resident undergraduates, at 70 percent. Thirteen other campuses have transfer representation percentages above 50 percent. Two campuses fall under the 33 percent goal: Cal Maritime is at 29 percent and Cal Poly San Luis Obispo is at 18 percent. A box below the bar chart explains that for Cal Poly San Luis Obispo to have met the 33 percent transfer representation goal, it would have needed to enroll about 700 to 1100 additional transfer students annually, depending on whether it admitted equivalently fewer freshmen or simply increased its enrollment capacity while admitting the same number of freshmen.

Although the CSU system as a whole easily met the one‑third benchmark, the campuses’ individual success in meeting this goal varied. As Figure 9 shows, all but two CSU campuses enrolled more than 45 percent of their incoming student body as transfer students. However, California State University Maritime Academy (Cal Maritime) and Cal Poly San Luis Obispo enrolled just 29 percent and 18 percent, respectively. The percentage Cal Maritime enrolled was just below the one‑third mark, which is likely because the campus offers limited and specialized courses of study and enrolls few students. In contrast, low transfer representation paired with high denial rates for transfer applicants may be a cause for concern at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, the most competitive campus for transfer applicants of any campus in the CSU or UC systems. Certain majors at other CSU campuses present a similar concern. We discuss both of these issues in the next section.

CSU fairly consistently admits transfer applicants from each major demographic group, although its admission rate is lower for Black or African American students than for students in general. Table B.3 in Appendix B shows CSU’s admission rates by demographic group for community college transfer applicants during our audit period. Of note, CSU admitted 66 percent of Black or African American transfer applicants, which is about 4 percentage points lower than the percentage of all transfer applications it admitted. This gap generally aligns with CSU’s public dashboard, which displays unduplicated totals and shows that, on average, about 84 percent of Black or African American transfer applicants gained admission systemwide compared to 88 percent of all applicants.5 The assistant vice chancellor of institutional research and analysis at the CSU Chancellor’s Office stated that data showed Black or African American applicants were slightly more likely, relative to other groups, not to meet minimum CSU eligibility or to have incomplete or withdrawn applications. System officials are aware of this gap and stated that they have recently instituted programs to address it by easing the transfer application process, including its Black Student Success initiative, Transfer Success Pathway, and CSU Transfer Planner.

Transfer Students May Struggle to Gain Admission to Their Preferred CSU Campuses and Majors

Transfer students are more likely to enroll at CSU if they are admitted to their preferred campus and major.6 However, certain CSU campuses and certain majors at some CSU campuses do not have the capacity to accommodate all of the eligible students who apply to them. CSU generally refers to this situation as impaction and has adopted a redirection policy to avoid denying those students admission to programs at other campuses that are not impacted. The text box shows the seven impacted CSU campuses and key impacted majors at other campuses for undergraduate students in academic year 2023–24.

CSU’s Impacted Campuses and Key Impacted Majors in Academic Year 2023–24

Impacted campuses:

- Fresno State*

- Cal State Fullerton

- Cal State Long Beach

- Cal State LA

- San Diego State

- San José State

- Cal Poly San Luis Obispo

Key majors that are impacted at some non-impacted campuses:

- Biological Sciences

- Business

- Criminology/Criminal Justice

- Engineering

- Nursing

- Psychology

Source: CSU website.

* Fresno State was no longer impacted as of Fall 2024.

Impacted CSU campuses and majors generally have lower admissions rates. For example, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo and San Diego State had the lowest campus transfer admission rates—19 percent and 30 percent, respectively—from academic years 2018–19 through 2022–23, as Table B.2 in Appendix B shows. Moreover, these two campuses admitted transfer applications to their computer science majors at rates of just 8 percent and 13 percent, respectively.

When CSU does not admit eligible students to the campuses and majors to which they have applied, it instead uses a process outlined in its redirection policy to offer those students the opportunity for admission to campuses that can accommodate them in the same or similar majors.7 The text box shows the minimum eligibility requirements for upper‑division transfer students. To carry out the redirection process, CSU identifies all eligible resident applicants who did not gain admission to the CSU campuses to which they applied and allows them the opportunity to select a first‑ and second‑choice campus that is not impacted. CSU then routes these applicants to either their selected campuses, if they have enrollment capacity, or to campuses that have enrollment capacity.

CSU’s Minimum Eligibility Requirements for Upper-Division Transfer Students

Applicants must complete at least 60 semester (90 quarter) units of CSU-transferable credit and earn a 2.0 GPA in all transferable units attempted. The units must including the following:

- At least 30 semester (45 quarter) units of CSU‑transferable general education credit.

- One transferable course in written communication, oral communication, and critical thinking with a grade of C- or better.

- One transferable course in mathematics or quantitative reasoning with a grade of C- or better.

Impacted CSU campuses and majors are authorized to use supplemental admission criteria to screen applicants. For example, San Diego State generally requires applicants to complete all preparation for major courses listed in the campus’s catalog.

Source: State law, CSU 2023–24 Admission Handbook, and San Diego State’s website.

CSU redirects most transfer students from three of its most competitive campuses: Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, San Diego State, and Cal State Long Beach. According to data that CSU provided, it redirected more than 25,000 community college transfer applicants during academic years 2019–20 through 2022–23. However, during the same period, only a very small number of these transfer students actually enrolled through CSU’s redirection process—about 1,700 students, or 7 percent.

Since the Fall 2019 term, CSU has used between seven and 10 campuses for redirection because these campuses have the necessary capacity. However, during academic year 2023–24, five of the seven redirection campuses were located in Northern California, while the majority of the impacted campuses were located in Southern California. According to the results of a CSU survey of the students it redirected, the two most common reasons among respondents for not enrolling were an inability to relocate and not wanting to attend any of the available campuses. These reasons signal that transfer students are less likely to enroll at a redirection campus.

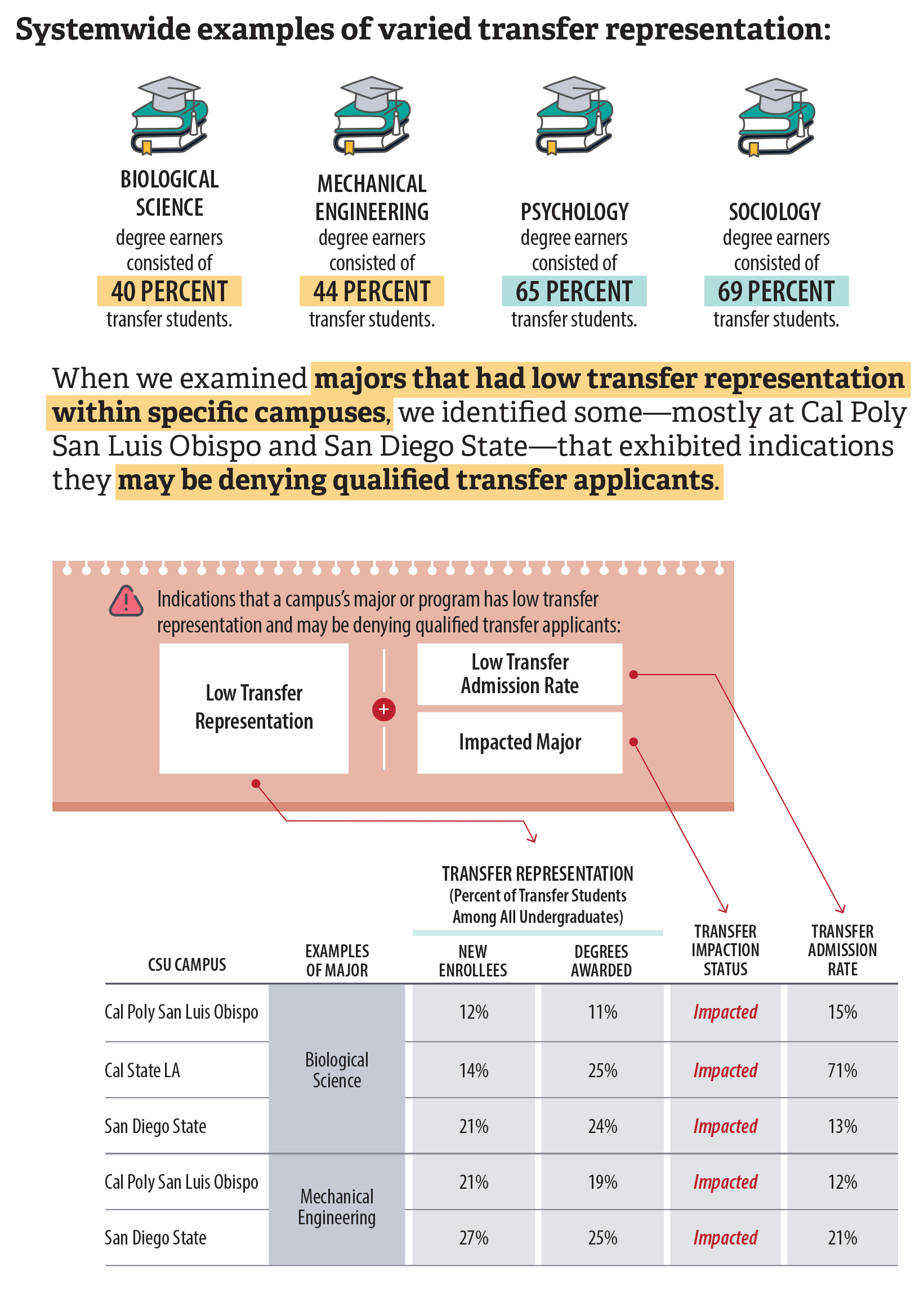

Transfer students may lack access to their preferred campuses and majors in part because Cal Poly San Luis Obispo and certain competitive majors at other campuses disproportionately consist of freshmen instead of transfers. As we describe previously, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo has the lowest transfer representation in the CSU system and enrolls significantly less than one‑third of its incoming students through transfer. Moreover, the campus enrolls less than one‑third in 17 of its 19 academic disciplines, and for the remaining two disciplines, the transfer representation among students who graduate—a metric we discuss in more detail in the next paragraph—was also less than one‑third. Other campuses similarly enroll low proportions of transfer students in some disciplines or majors, but not to the extent of Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. For example, from 2018 through 2023, transfer students represented just 21 percent and 27 percent of new resident enrollees in San Diego State’s biological science major and computer science major, respectively. However, transfer students comprised 48 percent of new resident students for the campus as a whole during that same period. In general, transfer students are less represented in STEM majors and disciplines than they are in other majors and disciplines. Figure 10 highlights some of our concerns in this area.

Figure 10

Transfer Representation Varied Significantly Among Specific Majors at CSU Campuses

Source: Analysis of CSU application, enrollment, and degree data.

Note: For the purpose of this graphic, we calculated levels of transfer representation and admission rates using data from 2018 through 2023, meaning that the totals and percentages cover five academic years. Further, we calculated transfer representation among only students with California residency.

Figure 10 is a diagram that shows that transfer representation varied significantly among specific majors at CSU campuses and that some majors with low transfer representation may be denying qualified transfer applicants. The top of the graphic shows that systemwide, CSU majors such as biological science and mechanical engineering had lower transfer representation than other majors did, such as psychology and sociology. Below those examples, the graphic explains that when examining majors that had low transfer representation, we identified some that exhibited indications that they may be denying qualified transfer applicants—such as the majors being impacted and having a low transfer admission rate. A table provides specific examples of impacted biological science and mechanical engineering majors at certain CSU campuses and shows their transfer representation percentages, their impaction status, and their transfer admission rates.

In response to our questions about lower transfer representation in certain campuses and majors, CSU officials explained that using new student enrollment data to measure transfer representation is problematic because many freshmen change majors after they initially enroll. For example, the associate vice president for enrollment management at San Diego State provided us with a student migration dashboard for the campus that showed that freshmen migrate out of STEM majors at higher rates than they do for other majors. Even so, when we analyzed graduation data—which considers only those students who ultimately earned a degree—we still found that certain CSU majors, such as biological sciences at San Diego State, awarded fewer than one‑third of their degrees to transfer students. In other words, transfer representation remained low for many majors even when we adjusted for freshmen changing their majors.

One more factor that could affect a campus’s or major’s level of transfer representation is the number of qualified transfer applicants. If a campus or major with low transfer representation also denies qualified transfer applicants, it may indicate that the campus or major is not adequately prioritizing transfer applicants compared to freshmen applicants. Determining whether transfer applicants are qualified for admission is complicated because campuses and majors use different approaches to assessing qualifications. Although transfer applicants to CSU are generally qualified if they meet the minimum eligibility requirements that the text box shows, impacted campuses and majors may impose supplemental admission criteria to further screen applicants. The very fact that a campus or major is impacted suggests that it is competitive and more likely to deny even applicants who exceed CSU’s minimum eligibility requirements. In addition, when a campus or major has a low admission rate—meaning it denies most transfer applicants—it is another indication that the campus or major may be denying applicants who meet its supplementary criteria.

We assessed whether certain impacted campuses and majors were denying qualified applicants. Figure 10 includes some examples of majors that are impacted and that had low transfer representation—among both new enrollees and degrees awarded—and low transfer admission rates. Based on these indicators and other factors, including conversations with campus officials and our analysis of other available data, we believe that Cal Poly San Luis Obispo and certain impacted majors within other campuses may have denied transfer applicants that met their supplementary admissions criteria. For example, Cal Poly San Luis Obispo denied 81 percent of transfer applications during our audit period, with about 9,400 of those denied applications reporting grade point averages (GPAs) of 3.6 or higher. Although we did not formally audit Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, when we followed up with the campus about some of our findings, its vice president of strategic enrollment management confirmed that the campus has not offered admission to all qualified transfer applicants—meaning applicants who were minimally eligible and also met its campus‑ and major‑specific admissions requirements. The vice president attributed this outcome to high application demand and limited capacity in certain majors, such as business and computer science, and added that the campus has offered admission to all qualified applicants in many other majors and to the vast majority of qualified applicants who are considered local to the campus. Similarly, San Diego State’s associate vice president for enrollment management acknowledged that some impacted majors, such as biological sciences, have denied transfer applicants who meet the major’s admissions requirements, although campus officials identified that recent trends show higher transfer admission rates in Fall 2023 and 2024, including in high‑demand majors.

Ultimately, it is incumbent on the CSU Chancellor’s Office to identify whether a particular campus or major has low transfer representation and, if so, to ensure that the campus or major is offering admission to as many qualified transfer applicants as possible. In the next section, we discuss ways in which the CSU Chancellor’s Office could explore increasing transfer representation in certain campuses and majors, even when limited capacity exists. Doing so would be consistent with the Legislature’s intent that the transfer system be implemented in such a way as to ensure the successful transfer of students to CSU and UC, including the campus and major of their choice, if academic performance is satisfactory.

When Limited Capacity Exists, CSU Can Better Prioritize the Admission of Transfer Students

As the text box describes, three main factors affect enrollment capacity. Taking all three factors into account, CSU has capacity for enrollment growth, although not evenly distributed across all its campuses. For example, CSU projected in January 2023 that it would have budget capacity to enroll at least 25,000 additional California resident students by the end of academic year 2022–23. However, most of that additional budgeted capacity is at seven non‑impacted CSU campuses, primarily located in Northern California, including Chico State University (Chico State); California State University, East Bay (Cal State East Bay); California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt (Cal Poly Humboldt); Cal Maritime; San Francisco State University (San Francisco State); Sonoma State University (Sonoma State); and California State University Channel Islands (CSU Channel Islands).

Three Main Factors Affect Enrollment Capacity

The physical capacity of a campus is determined by the number of people a campus is able to accommodate spatially.

The operational capacity of a campus is determined by the number of faculty and staff.

The budgeted capacity of a campus is determined by the number of full-time students whom the campus can serve with the amount of state funding it receives.

Source: CSU capacity study and public reports.

Shifting funding from campuses with budgetary capacity to impacted campuses could increase the number of transfer students that CSU enrolls. CSU has developed a plan to accommodate enrollment growth at its impacted campuses: in January 2023, it published the Enrollment Target and Budget Reallocation Plan with an explicit goal to reallocate funding from campuses not meeting funded enrollment targets to those that have been meeting them. If CSU achieves this goal, impacted campuses that currently deny many transfer applicants—such as Cal Poly San Luis Obispo—could have more room to accept some of those students.

CSU could make the most effective use of capacity increases—and potentially of the capacity it already has—by establishing an explicit transfer representation goal for its campuses and their programs. As we describe in the Introduction, state law seeks to ensure that adequate spaces are reserved for transfer students by establishing a metric for upper‑division enrollment, but it does not formalize a metric specifically related to transfer enrollment—such as the one‑third transfer representation goal we discuss throughout this chapter. Further, CSU’s assistant vice chancellor of enrollment management services stated that CSU does not explicitly maintain such a transfer representation goal or use it for admission purposes. For example, the assistant vice chancellor for finance and budget administration confirmed that the CSU Chancellor’s Office provides campuses with an overall funded enrollment target for resident students, but it does not provide campuses—including Cal Poly San Luis Obispo—with any targets for enrolling a certain number of transfer students specifically.

In addition, San Diego State provided examples of its program‑level enrollment targets for academic year 2022–23 that showed the targets themselves were below one‑third for transfer students in some impacted majors like biological science and computer science. The associate vice president for enrollment management at San Diego State provided context for these targets, including various factors—such as being asked to enroll more students than anticipated—that led the campus to increase its overall enrollment target for freshmen students but not for transfer students that year. The vice president noted that increasing upper‑division capacity typically requires more time to plan and hire faculty than increasing lower‑division capacity does. Even so, these types of challenges underscore the potential benefits of having a mechanism in place to monitor transfer representation and a plan to increase transfer student enrollment in particular campuses and programs when warranted.

CSU system officials expressed concerns that enrolling additional transfer students might disadvantage freshmen. When limited capacity exists, enrolling a greater number of transfer students could mean denying more freshmen applicants in certain campuses or majors—although not necessarily systemwide. Although state law provides that CSU and UC must achieve the upper‑division enrollment goal that we explain in the Introduction through programs aimed at increasing the numbers of qualified CCC transfer students without denying eligible freshman applicants, state law also requires campus enrollment plans to include adequate spaces for community college transfer students in all undergraduate colleges or schools. The Legislature also intends that CSU and UC prioritize the admission and enrollment of CCC students who have met transfer requirements over students entering at the freshman or sophomore levels. Further, state law authorizes the CSU Chancellor’s Office to establish enrollment quotas for each campus and, in doing so, it is required to place primary emphasis on the allocation of resources at the upper‑division level in order to help accommodate CCC transfers. If a particular campus or major has been using an enrollment process that clearly favors freshmen at the expense of transfer students, changing that process may be reasonable.

CSU could also explore options to increase transfer representation that allow it to maintain the number of freshmen it enrolls. For example, the CSU Chancellor’s Office could work with campuses and majors that may be denying qualified transfer applicants despite having low transfer representation to identify why this situation is occurring and to ensure that the campuses are taking reasonable steps to accommodate transfer enrollment. As part of this process, CSU could consider prioritizing capacity increases for additional transfer enrollments rather than making room for transfer enrollments by reducing freshmen enrollments. Alternatively, from a systemwide standpoint, the CSU Chancellor’s Office could consider whether it could offset any reductions in freshmen enrollment at particular campuses or majors by increasing freshmen enrollment at campuses or majors with higher transfer representation.

Another way in which CSU can increase transfer students’ access to their preferred campuses and majors is by continuing to seek opportunities to prioritize local transfer students for admission. In accordance with provisions such as the Budget Act of 2017, CSU has a process that requires campuses to give priority to local applicants who are eligible for transfer and seek to enroll in impacted programs. CSU’s process for prioritizing local students for admission allows each campus to determine the precise type and degree of local preference. For example, a 2023 CSU report stated that California State University, Fullerton (Cal State Fullerton) provided a GPA advantage of 0.4 to local transfer applicants. The report also stated that San Diego State selected local transfer applicants first in its ranking process, before any nonlocal applicant with equal preparation or GPA. These types of strategies help CSU continue to admit and enroll transfer students in line with the intent of state law.

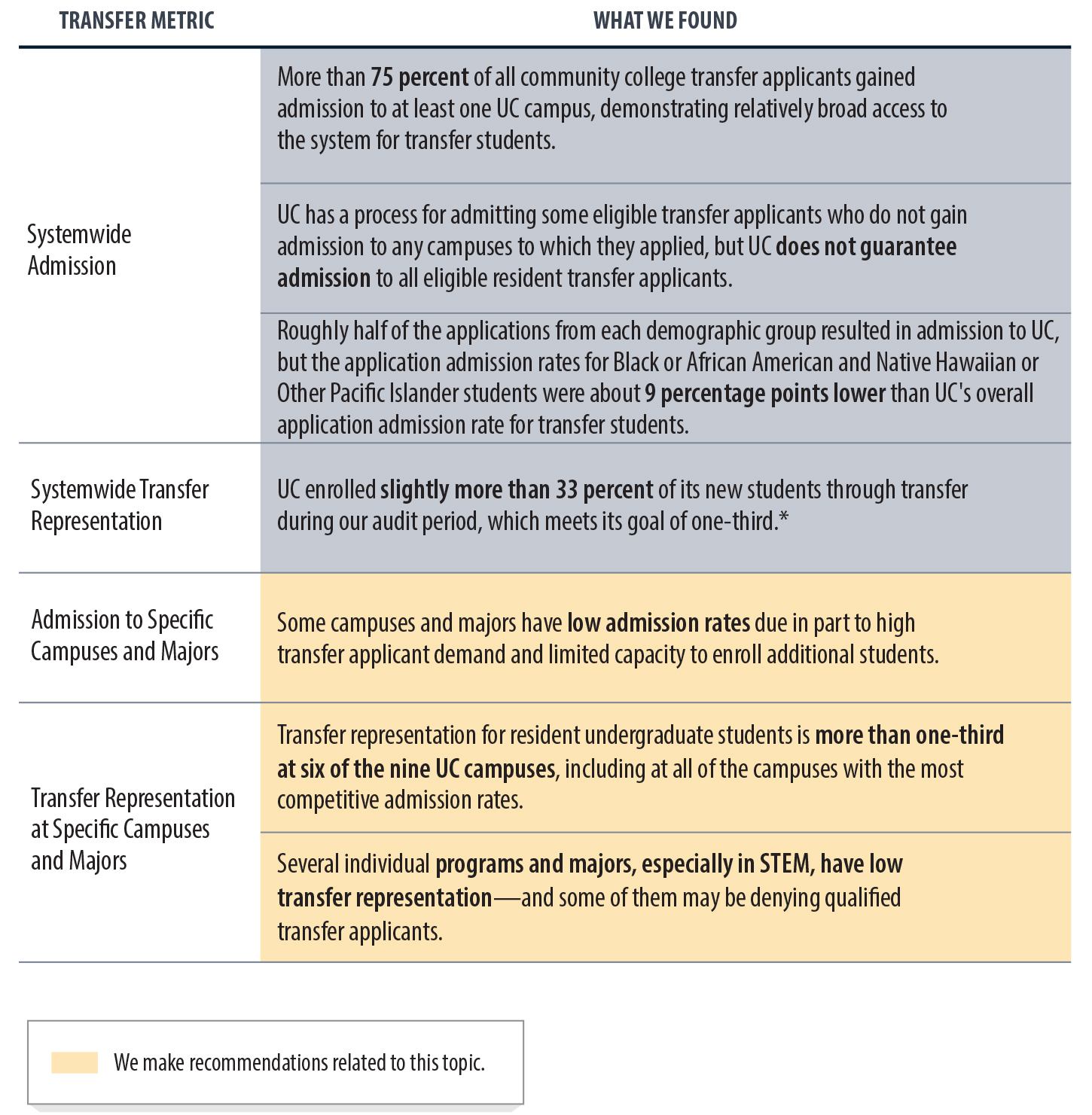

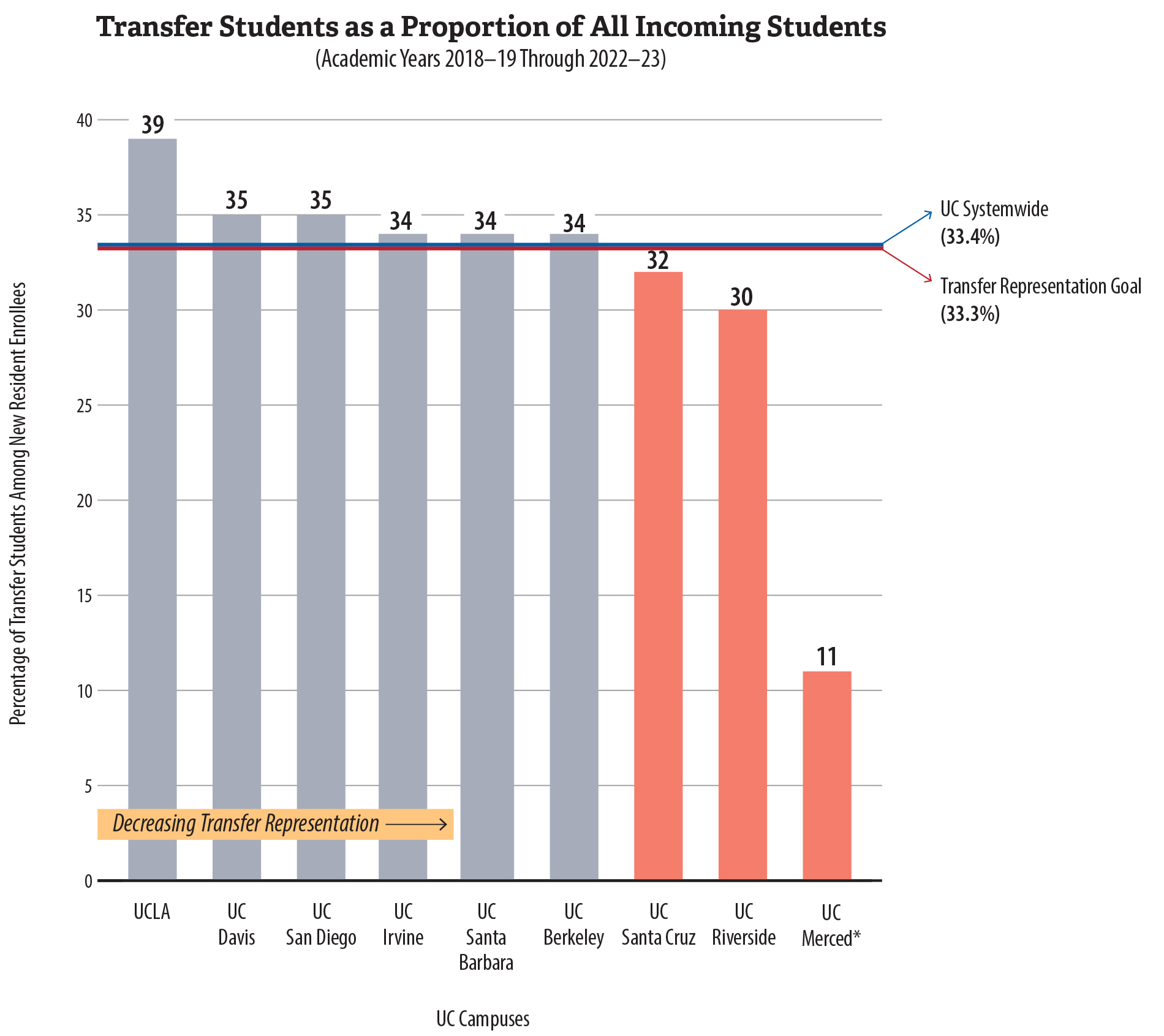

UC Accepts More Than 75 Percent of Transfer Applicants, but Its Admission Rates Are Significantly Lower for Certain Campuses and Majors

Although UC admits fewer of its transfer applicants and has lower transfer representation than CSU does, it has nevertheless met its systemwide transfer representation goal. Figure 11 shows that most community college transfer students who apply to UC gain admission to at least one campus, although not necessarily to their preferred campus or major. Students may prefer a particular campus or major for a variety of reasons, including the potential future employment opportunities associated with earning a degree. They must also meet requirements specific to that campus or major, as we discuss in Chapter 2. To increase the likelihood of transfer students enrolling in their desired fields of study, UC could do more to monitor and prioritize their admission to certain competitive campuses and majors.

Figure 11

UC Accommodates Many Transfer Students but Can Improve Access to Some Campuses and Majors

Source: Analysis of state law, the Master Plan, UC application and enrollment data, and other system documents.

* As we explain in the Introduction, we derived this goal—to enroll one‑third of new resident undergraduates through transfer—from a UC goal that is related to an upper‑division enrollment requirement in state law.