2023-122 Custodial Staffing and Cleanliness Standards

Significant Maintenance Deficiencies at Some Schools May Place Students’ Safety and Learning at Risk

Published: November 19, 2024Report Number: 2023-122

November 19, 2024

2023‑122

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of California Public School Custodial Cleanliness Standards, which included assessing the conditions of 18 public schools across six school districts: Calaveras Unified School District, Chico Unified School District, Fresno Unified School District, Los Angeles Unified School District, Palo Verde Unified School District, and Santa Maria-Bonita School District. Our evaluation focused on the custodial cleanliness standards and staffing at these public schools, and we determined that the schools had numerous maintenance deficiencies that may place students’ safety and learning at risk.

My office found that many schools are not meeting State standards for cleanliness and maintenance, exposing children to unsafe and unhealthful conditions that can affect their academic success. For example, we found improperly stored hazardous cleaning supplies in multiple schools we visited. We also observed among the schools we visited leaky roofs, structural deterioration, stained ceiling tiles, and fire safety issues, such as classrooms with missing fire extinguishers. We noted that schools lack a funding source dedicated to facilities maintenance because the school funding formula is based solely on attendance and student characteristics. We recommend that the Legislature consider developing a funding category for maintenance separate from the current school funding formula.

We also found that oversight of school facilities needs improvement. Using the same Facility Inspection Tool (FIT) that schools use to evaluate facility conditions, my office generally scored the schools lower than the schools scored themselves on their School Accountability Report Cards, and our FIT scores were generally lower than those from their respective county Offices of Education. Because the report cards are a way for the school to provide information on school conditions to the public, there may be an incentive for schools to rate themselves generously. Additional oversight of this process is necessary. Finally, we identified potential improvements to the FIT itself so that it will better reflect school conditions and be a better means of communicating information on school cleanliness and maintenance to the public.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| APPA | Association of Physical Plant Administrators |

| CDE | California Department of Education |

| DGS | Department of General Services |

| FIT | Facility Inspection Tool |

| FMPs | Facilities Master Plans |

| FTE | full-time equivalent |

| HVAC | heating, ventilation, and air conditioning |

| LAO | Legislative Analyst’s Office |

| LCFF | Local Control Funding Formula |

| NCES | National Center for Education Statistics |

| SARC | School Accountability Report Card |

Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations

Over the past 20 years, at least a dozen studies have demonstrated an adverse link between inadequate conditions at K-12 public schools and outcomes for students. These studies have found that when schools defer maintenance or fail to clean their facilities adequately, students can exhibit increased rates of absenteeism, more frequent illnesses, and lower average test scores. In an effort to ensure that students receive the maximum benefits from their education, schools conduct annual assessments of their campuses’ cleanliness, maintenance, and safety. The assessments—which schools perform using the Facility Inspection Tool (FIT)—compare the facilities at each school against Good Repair Standards that state law describes.

Our review found the following:

- None of the 18 schools we inspected in six school districts throughout the State maintained their facilities in a manner that meets every State standard for good repair. We most commonly assigned poor scores to their safety, structures, and interiors. Some of the deficiencies we identified—such as hazardous cleaning chemicals and propane tanks stored in classrooms—posed significant risks to students, and schools corrected those immediately. The deferred maintenance we identified, which included leaky roofs and stained ceiling tiles, may be in part because school districts no longer receive funding specifically dedicated to the maintenance of school facilities. Instead, maintenance costs are one of many competing priorities that school districts must address with their available funding.

- The 18 schools in our review self-reported FIT scores in their school accountability report cards that were often higher than the scores we assigned when we conducted our inspections. County offices of education and school districts—the entities to which state law assigns responsibility for overseeing the condition of the school facilities—have not consistently provided monitoring to ensure that school districts report reliable information.

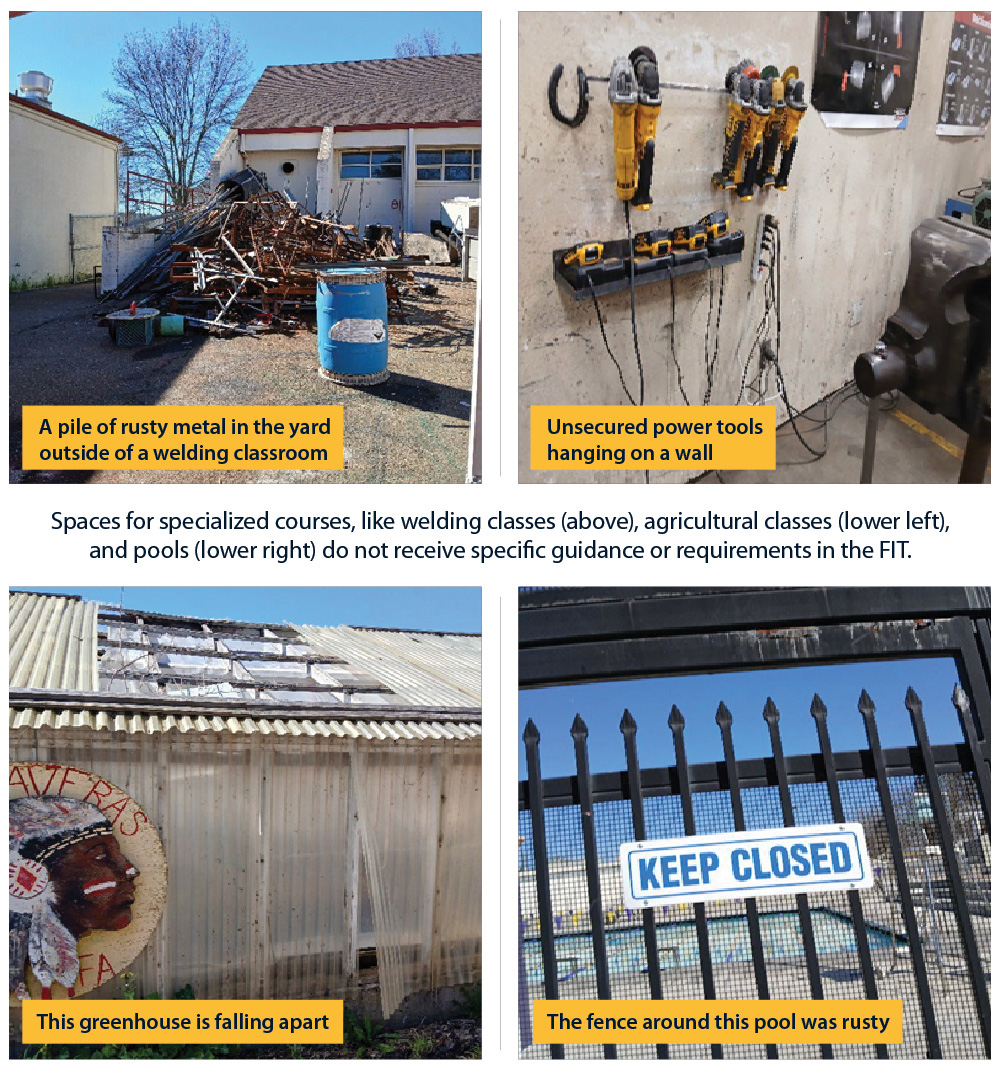

- The Department of General Services’ (DGS) Office of Public School Construction should make certain adjustments to the FIT to increase its effectiveness as an inspection tool. Specifically, because the FIT does not adequately consider the severity of deficiencies and does not account for the existence of multiple deficiencies in the same area, the FIT’s scores may not adequately communicate the magnitude of the cleanliness and maintenance concerns at schools. In addition, the FIT does not provide guidance on assessing the specialized classrooms often found in high schools, such as woodshops, automotive classrooms, and agricultural areas.

To address these findings, we have provided recommendations to the Legislature and to DGS. Our recommendations are designed to increase oversight of school facility conditions, provide dedicated funding for school maintenance, and ensure that the FIT provides adequate, accurate feedback on school cleanliness and maintenance.

Agency Perspective

DGS generally agreed with our recommendations. Because we did not make recommendations to the California Department of Education, the school districts, or county offices of education, no written response was required or expected from them; however, we did receive responses from Fresno Unified, Los Angeles Unified, and the Fresno County Office of Education. The Fresno County Office of Education raised concerns about redacted material, and Fresno Unified and Los Angeles Unified agreed in part but raised some concerns with our recommendations.

Introduction

Background

In academic year 2023–24, California’s approximately 10,000 public K-12 schools served more than five million students. Ensuring that these schools’ facilities are both safe and suitable for learning is critical to the health and education of the students who attend them. In the past 20 years, research has demonstrated an adverse link between inadequate facility conditions at public schools and student educational outcomes. For example, several studies found that poor cleanliness and maintenance conditions at public schools—such as dirty interior surfaces or old and poorly maintained buildings—correspond with increased rates of absenteeism and illness among students.1,2 Further, one study found that student absenteeism is more likely to occur at schools with visible mold and building condition problems, noting this association was most apparent in schools in lower socioeconomic districts.3

Research has also shown that the condition of public school facilities is linked to students’ academic performance. Specifically, when school facility conditions improve, so do performance outcomes, such as graduation rates. Unfortunately, the inverse is also true. For example, one study in Texas measured student academic performance against the age and condition of high schools. The study concluded that students who attended schools meeting the highest standard for facility conditions—which the study refers to as excellent, meaning no major repairs were needed—graduated at higher rates and scored higher on standardized tests than did students who attended schools in need of repair.4 Figure 1 shows some of the negative outcomes that can be associated with certain types of deficiencies.

Figure 1

Poor Classroom Cleanliness and Maintenance Can Negatively Affect Students and Their Academic Performance

Source: Several academic studies on various maintenance and cleanliness deficiencies and the negative effects they can have in a school setting.

Figure 1 is titled “Poor Classroom Cleanliness and Maintenance Can Negatively Affect Students and Their Academic Performance.” It is a picture of a classroom. At the window is a cloud with lines representing wind and the caption reads “Studies show a significant association between classroom-level ventilation rates and test results in math.” In a corner of the classroom near the ceiling is a vent for a heating and air condition system. The caption reads “Temperature can have a significant impact on students. One study concluded that without air conditioning, each additional degree the classroom temperature raises reduces learning by 1 percent.” There are stains on the ceiling and the wall. The caption reads “Water-stained ceiling tiles and walls can indicate excessive moisture, which can encourage the growth of mold and mildew. One study suggests that visible mold and mildew growth increases student absenteeism.” Another caption also points to the stains on the ceiling and the wall, as well as a stain on the floor and reads “Studies indicate that poor maintenance correlates with increases in truancy, suspensions, and up to 6 percent lower test scores.” The final caption also points to the window with the cloud and blowing wind and reads “One study found that students’ attention levels were 5 percent lower in poorly ventilated classrooms—similar to the outcome when a student skips breakfast.” The figure is sourced as “Several academic studies on various maintenance and cleanliness deficiencies and the negative effects they can have in a school setting.”

The Williams Case

In 2000, nearly 100 California school children filed a class action lawsuit against the State of California, the State Board of Education, the California Department of Education (CDE), and the California Superintendent of Public Instruction. The lawsuit alleged that these entities failed to meet a constitutional duty to ensure that all public school children have equal access to the basic educational tools they need to learn, including resources and facilities. The case, Eliezer Williams et al. v. State of California et al. (Williams) was settled in 2004. The settlement included a package of legislative proposals to ensure, in part, that students would have well‑maintained schools.

Following the Williams settlement, the Office of Public School Construction, which is under the authority of the Department of General Services (DGS), developed the Facility Inspection Tool (FIT) to provide a means of assessing the maintenance, cleanliness, and safety of school facilities. State law requires that school districts (districts) use the FIT, or an alternative tool they create which meets the same criteria, to perform such evaluations every year. The districts must publish the results of their annual FIT evaluation of each school in that school’s School Accountability Report Card (SARC). We describe the FIT in more detail in the next section.

After the Williams settlement, the Legislature appropriated $800 million in increased funding to address critical facility repairs at certain schools with poor academic performance (Williams schools) and increased oversight of Williams schools. Specifically, following the Williams settlement, the Legislature amended state law to require county superintendents to conduct annual inspections of all Williams schools within the districts that their county offices of education oversee. As part of these inspections, the county superintendents must determine the accuracy of the data the schools report on their SARCs regarding the safety, cleanliness, and adequacy of their facilities, including whether those facilities are in good repair. Finally, the Williams settlement required every district to use a uniform complaint process to identify and remedy complaints about emergency or urgent facility-related conditions (Williams complaints).

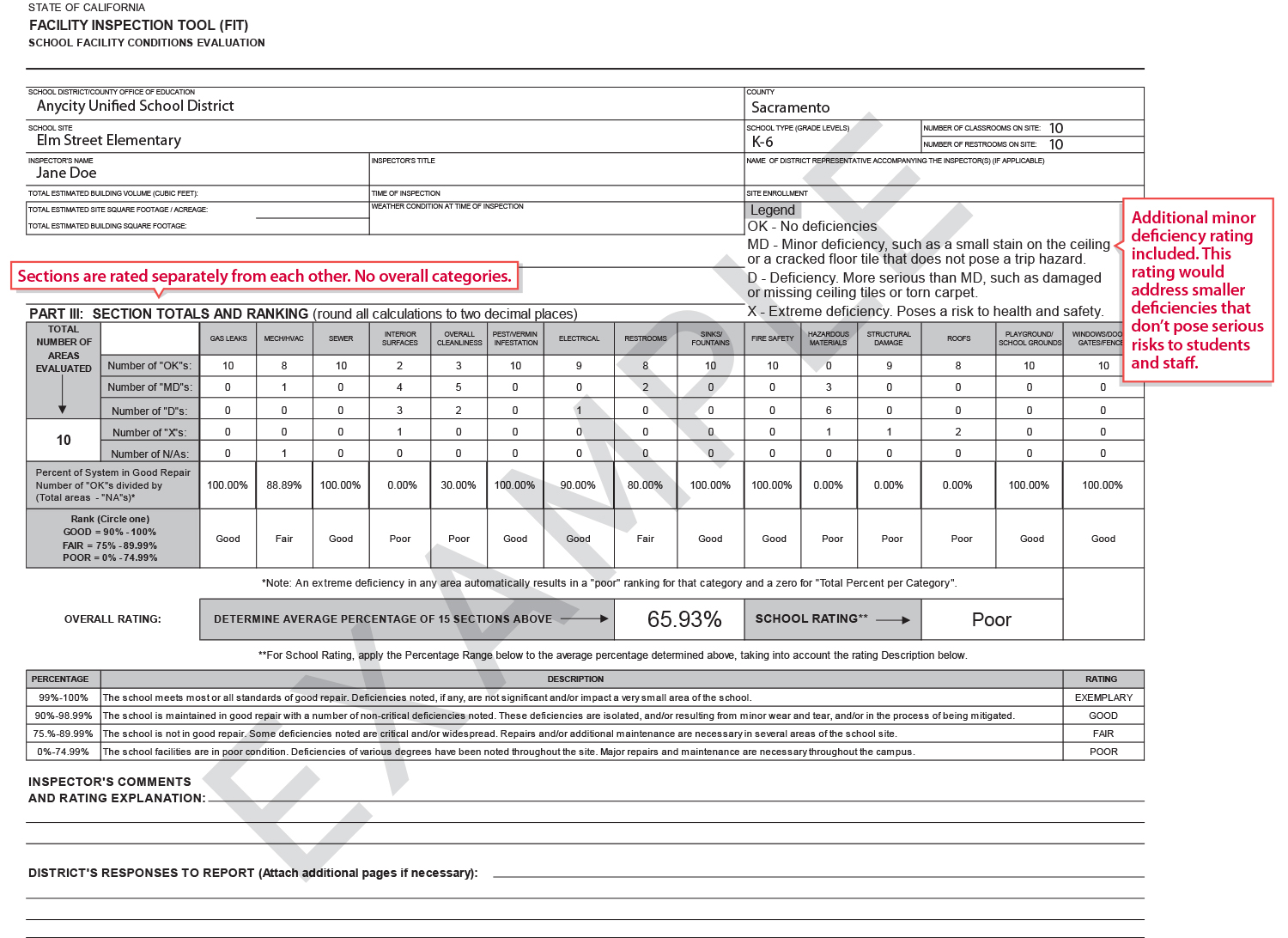

The FIT

State law requires districts to use the FIT or a similar tool to annually determine the adequacy of school facilities, identify needed maintenance, and ensure that schools are in good repair. State law defines good repair and outlines the school facility systems and components that inspectors should consider when assessing school facilities. For a school to meet the Good Repair Standards, the school must be maintained in a manner that assures it is clean, safe, and functional.

The FIT consists of 15 sections that identify the systems and components that an inspection of a school facility must consider. An inspector, who might be a school employee, district employee, or consultant, uses the FIT to evaluate the areas of a school on a section-by-section basis.5 Examples of FIT sections include Interior Surfaces, Overall Cleanliness, and Electrical Systems. Table 1 describes the 15 FIT sections and shows the eight categories into which they are grouped for SARC reporting. An inspector must use each of the 15 sections to evaluate locations such as classrooms, playgrounds, and restrooms, unless a particular section is not applicable to a location. For example, an inspector would generally not review a tennis court or running track under the Roofs section because these locations tend to be uncovered. An inspector might perform reviews at different times throughout the year, such as just after a deep cleaning during a winter break or at the end of a school day, which might affect observed school conditions in that moment.

After evaluating the conditions present in each location, the inspector makes a determination of whether a particular area is in good repair by assigning one of four possible FIT scores. The text box defines these scores. For example, a drinking fountain would be scored OK if it was accessible, functioning as intended, and did not have a deficiency, such as mold or excessive staining on the fixtures. An inspector would assign a deficient rating for a roof if the roof or its fixtures, such as gutters, had visible damage. Ratings of extreme deficiency require immediate attention and can include gas pipes that are broken or do not appear to be in good working order.

FIT Ratings

- OK: All statements in the section’s Good Repair Standards are true, and there is no indication of a deficiency.

- Deficient: One or more statement(s) in the Good Repair Standards for the section is not true, or there is other clear evidence of the need for repair.

- Extreme Deficiency: One or more of the extreme deficiencies described in the Good Repair Standards for the section are present; there is a condition that qualifies as an extreme deficiency but is not noted in the Good Repair Standards; or there are one or more deficiencies that meet the definition of an extreme deficiency: a deficiency that is critical to the health and safety of pupils and staff and that, if left unmitigated, could cause severe and immediate injury, illness, or death.

- Not Applicable: The Good Repair Standards section (building system or component) is not relevant in the evaluated area.

Source: The FIT.

Using the individual scores for locations throughout the school, the inspector must then assign the school an overall score, which the school publishes in its SARC. Figure 2 shows the process the inspector must follow to determine the school’s average FIT score for each section reported in the SARC. The inspector then uses this information to assign the school’s overall FIT score—exemplary, good, fair, or poor—as the text box describes. For more information about how schools complete these calculations, see Figure 2.

Figure 2

Example of Calculation of FIT Score for the SARC Safety Category

Source: State Auditor.

Table 1 shows how the FIT sections comprise SARC categories.

Figure 2 is titled “Example of Calculation of FIT Score for the SARC Safety Category.” The figure outlines four steps. Step One: After Conducting the Inspection, the Inspector Determines the Total Number of Areas That the Inspector Evaluated. The inspector counts the evaluated areas, classrooms, and outdoor facilities such as fields and tennis courts. For example, 32 areas evaluated. Step Two: Determine the Number of Areas That Received Each Score. The inspector then counts the number of areas that received each rating across the 15 sections. In this example, the inspector counts the number of ratings assigned to each area for the Hazardous Materials and Fire Safety sections and deducts any areas rated as Not Applicable. For example, in FIT Section for Hazardous Materials with Total Number of Areas in Each Section calculated from 17 OK ratings plus 15 Deficient ratings plus zero Extremely Deficient ratings minus zero Not Applicable ratings equals 32 Total Number of Areas in Each Section. In another example, FIT Section B Fire Safety Total Number of Areas in Each Section calculated from 31 OK ratings plus 1 Deficient rating plus zero Extremely Deficient ratings minus zero Not Applicable ratings equals 32 Total Number of Areas in Each Section. Step Three: Determine Section Scores. The inspector then divides the number of areas with OK ratings by the total number of areas evaluated in each section. Fit Section A for Hazardous Materials equation 17 divided by 32 equals 53 percent. FIT Section B for Fire Safety equation 31 divided by 32 equals 97 percent. Step Four: Determine the SARC Category’s Score (see footnote). The inspector combines the scores for the sections included in the category. In this example, the inspector is calculating the score for the Safety category, which includes the Hazardous Materials and Fire Safety sections. Equation is Section A score plus Section B score divided by the number of sections. For example, 0.53 plus 0.97 divided by 2 equals 0.75. The FIT classified category scores from 75 percent to 89.99 percent as fair. For example, Category Score equals 75 percent, Fair.

Funding for School Cleanliness and Maintenance

A school’s janitorial services and maintenance services differ significantly in terms of practice, purpose, and in some circumstances, funding sources. Janitorial services include daily cleaning tasks, such as emptying trash cans, vacuuming classrooms, and cleaning restrooms. In contrast, maintenance services focus on solving and preventing problems, such as replacing deteriorating wood or filling in potholes in the school parking lot. Districts pay for janitorial staff salaries and supplies through their general funds. However, the School Facility Program (facilities program) may provide funding for school facility projects.6

SARC Score

- Exemplary (99-100 percent): The school meets most or all of the Good Repair Standards. Deficiencies noted, if any, are not significant and/or affect a very small area of the school.

- Good (90-98.99 percent): The school is maintained in good repair with a number of noncritical deficiencies noted. These deficiencies are isolated, may be the result of minor wear and tear, and/or are in the process of being mitigated.

- Fair (75-89.99 percent): The school is not in good repair. Some deficiencies noted are critical and/or widespread. Repairs and/or additional maintenance are necessary in several areas of the school site.

- Poor (under 75 percent): The school facilities are in poor condition. Deficiencies of various degrees have been noted throughout the site. Major repairs and maintenance are necessary throughout the campus.

Source: The FIT.

Funded largely by $42 billion in voter‑approved bonds, the facilities program assists districts with funding facility modernization and alteration. The State Allocation Board (Allocation Board)—which the Office of Public School Construction staffs—is responsible for the distribution of grant funds under the facilities program. Once the Allocation Board determines that a school district is eligible, the district may obtain funding for improvements such as modernization projects. These projects can include replacing a school’s roof or other major infrastructure. However, school districts must meet a variety of eligibility requirements before receiving funding from the facilities program. For example, modernization projects require districts to provide 40 percent of the necessary funding themselves, with certain exceptions for demonstrated financial hardship. As of 2024, the facilities program had about $370 million available.

According to the Public Policy Institute of California, factors such as local property taxes, voters’ willingness to approve bonds, and a district’s ability to successfully complete the application process for the facilities program significantly influence the funding available to the district. For example, districts that participate in the facilities program must create a restricted fund for maintenance. State law generally requires that districts deposit a minimum of 3 percent of their total general fund expenditures into this fund each fiscal year for 20 years after their receipt of facilities program funds. Districts use the funds they deposit into this restricted account to make necessary repairs to projects that were funded in part through the facilities program and to ensure that projects funded by the facilities fund are maintained in good repair at all times.

School districts may create additional restricted funds, such as a deferred maintenance account. State law allows the governing board of a district to establish such a fund for major repair or replacement of school facilities’ systems and components, such as plumbing, heating, and roofing.

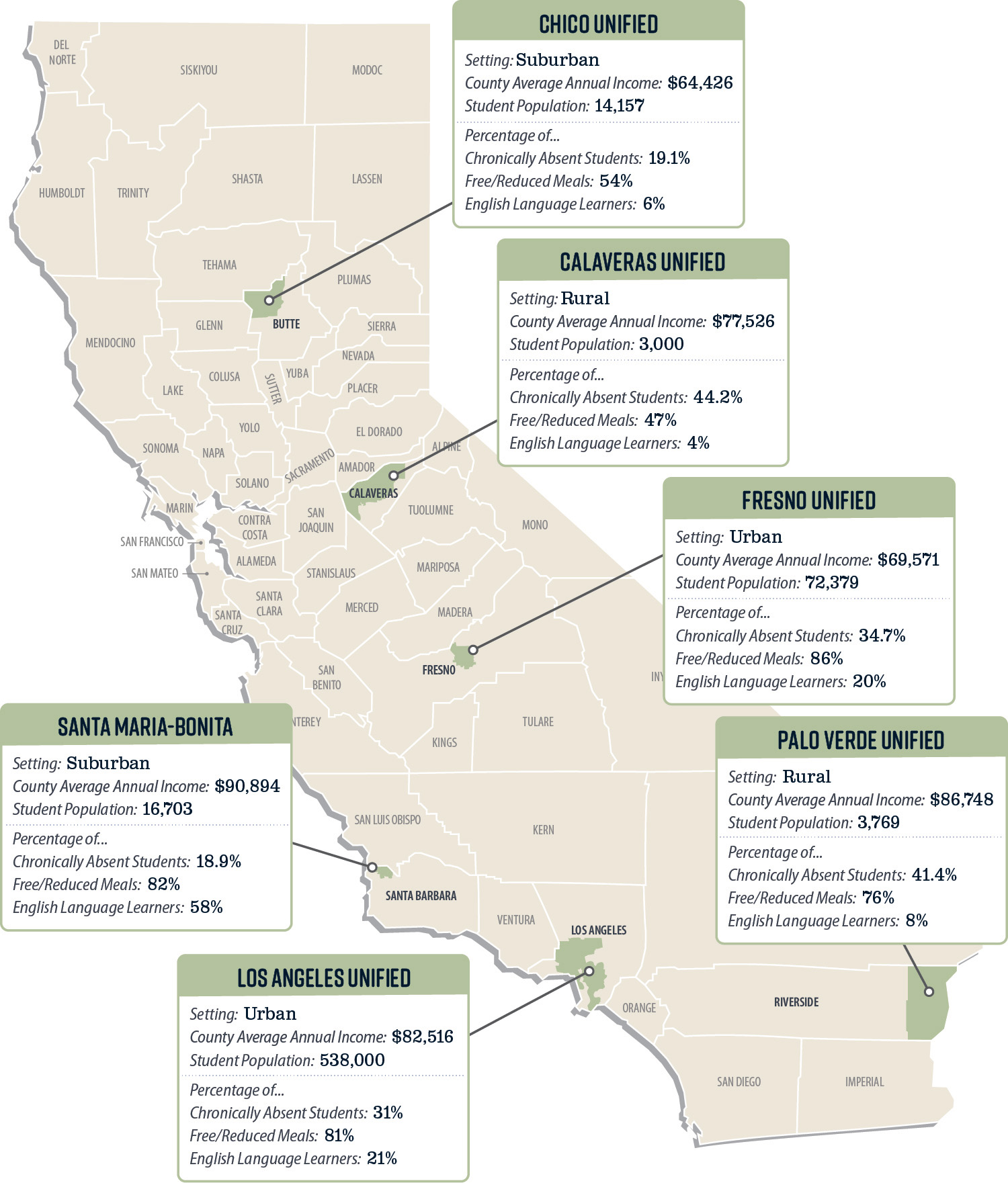

Districts Selected for This Audit

We considered a wide range of factors when selecting the districts we reviewed for this audit. Using data from CDE, the U.S. Census, and reviewed SARCs, we selected districts with varying enrollment levels, absence rates, and population socioeconomic statuses. We also considered factors such as average county incomes, student demographics, the percentages of students enrolled in free or reduced meals, and geographic locations. We ultimately selected the following six districts: Calaveras Unified School District (Calaveras Unified), Chico Unified School District (Chico Unified), Fresno Unified School District (Fresno Unified), Los Angeles Unified School District (Los Angeles Unified), Palo Verde Unified School District (Palo Verde Unified), and Santa Maria-Bonita School District (Santa Maria-Bonita). Figure 3 provides information related to each of our selected districts. We inspected three schools per district, for a total of 18 inspections.

Figure 3

Map and Details for Each Selected District

Source: CDE and U.S. census data.

Figure 3 is titled “Map and Details for Each Selected School District.” The figure is a map of California and its 58 counties. The map calls out six school districts and provides details on each district. Chico Unified. Setting is Suburban. County Average Annual Income is 64426 dollars. Student Population is 14157. Percentage of Chronically Absent Students is 19.1 percent. Free/Reduced Meals is 54 percent. English Language Learners is 6 percent. Calaveras Unified. Setting is Rural. County Average Annual Income is 77526 dollars. Student Population is 3000. Percentage of Chronically Absent Students is 44.2 percent. Free/Reduced Meals is 47 percent. English Language Learners is 4 percent. Fresno Unified. Setting is Urban. County Average Annual Income is 69571 dollars. Student Population is 72379. Percentage of Chronically Absent Students is 34.7 percent. Free/Reduced Meals is 86 percent. English Language Learners is 20 percent. Santa Maria-Bonita school district. Setting is Suburban. County Average Annual Income is 90894. Student Population is 16703. Percentage of Chronically Absent Students is 18.9 percent. Free/Reduced Meals is 82 percent. English Language Learners is 58 percent. Palo Verde Unified. Setting is Rural. County Average Annual Income is 86748 dollars. Student Population is 3769. Percentage of Chronically Absent Students is 41.4 percent. Free/Reduced Meals is 76 percent. English Language Learners is 8 percent. Los Angeles Unified. Setting is Urban. County Average Annual Income is 82516 dollars. Student Population is 538000. Percentage of Chronically Absent Students is 31 percent. Free/Reduced Meals is 81 percent. English Language Learners is 21 percent. The figure is sources from the California Department of Education and the United State Census.

Issues

Without Effective Oversight, School Facilities Will Remain in Poor Condition

The FIT’s Deficiency Rating System Does Not Accurately Reflect School Conditions

The School Districts We Reviewed Did Not Comply With Facility Requirements, Risking Student Learning and Safety

Key Points

- All 18 schools we reviewed across California failed to meet the Good Repair Standards set by state law. Our inspections most commonly assigned these 18 schools poor or fair scores in the Safety and Interior categories. Many of the deficiencies we identified were the result of deferred maintenance.

- Since fiscal year 2013–14, the State has not allocated districts funding specifically for the maintenance of school facilities. Instead, maintenance costs compete with other priorities, such as instruction or special education, that districts must align with the funding they receive through the State’s Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) and from local sources.

Our Selected Districts Face a Variety of Maintenance, Safety, and Cleanliness Challenges

State law requires districts to assess the safety, cleanliness, and adequacy of school facilities, including identifying any maintenance necessary to ensure the facilities are in good repair. Further, under state law, a district’s governing board or superintendent is responsible for visiting schools and carefully examining school needs and conditions. Nonetheless, as Table 2 demonstrates, all 18 schools we inspected failed to meet various elements of the Good Repair Standards in state law.

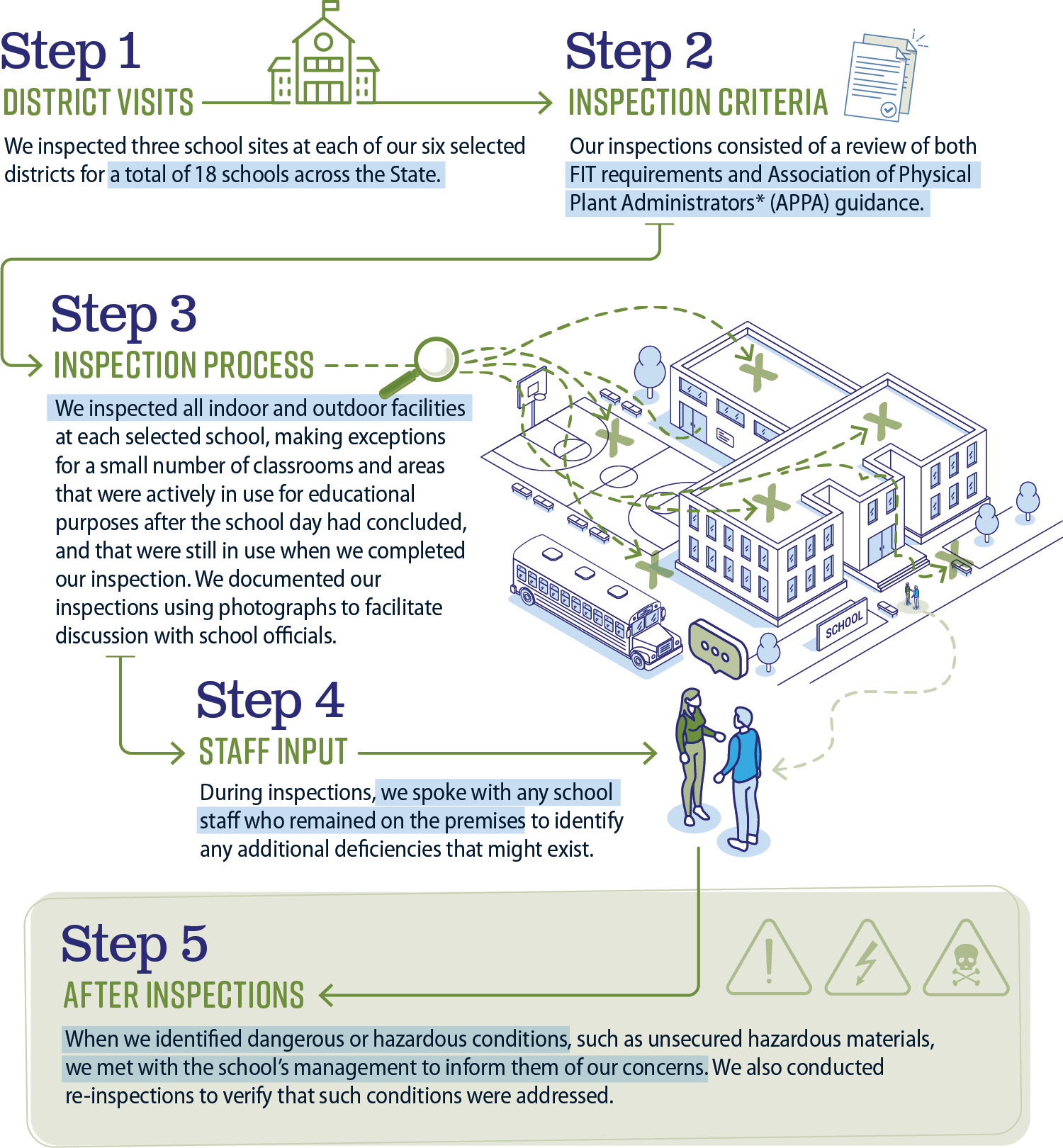

Our inspections most commonly assigned schools poor or fair scores to areas involving the FIT’s Safety and Interior categories. Some of these scores resulted from general maintenance and cleanliness problems. However, other low scores resulted from significant safety deficiencies, such as the presence of unsecured hazardous materials in classrooms. Figure 4 shows the inspection process we followed at each school to determine the scores we assigned.

Figure 4

Our Office Developed a School Site Inspection Process to Determine FIT Scores

Source: State Auditor.

*Refer to this section for more detail regarding the APPA.

Figure 4 is titled “Our Office Developed a School Site Inspection Process to Determine FIT Scores.” The figure outlines five steps to describe the process the auditors took to rate each school. Step one: District visits. We inspected three school sites at each of our six selected districts for a total of 18 schools across the State. Step two: Inspection criteria. Our inspections consisted of a review of both FIT requirements and Association of Physical Plant Administrators (see footnote) (APPA) guidance. Step three: Inspection process. We inspected all indoor and outdoor facilities at each selected school, making exceptions for a small number of classrooms and areas that were actively in use for educational purposes after the school day had concluded, and that were still in use when we completed our inspection. We documented our inspections using photographs to facilitate discussion with school officials. Step four: Staff Input. During inspections, we spoke with any school staff who remained on the premises to identify any additional deficiencies that might exist. Step five: After inspections. When we identified dangerous or hazardous conditions, such as unsecured hazardous materials, we met with the school’s management to inform them of our concerns. We also conducted re-inspections to verify that such conditions were addressed.

The causes of these deficiencies varied. For example, districts told us that they have policies against having unsecured hazardous materials in classrooms. They explained that in many cases, teachers brought in the hazardous materials we observed—such as cleaning wipes and bug spray. However, some of the hazardous materials we found in the classrooms, including industrial-strength cleaners, were district-issued. We observed during reinspections that after we brought our observations to the districts’ attention, they corrected the deficiencies. Thus, we believe the core cause of these types of deficiencies is likely neither a lack of policies nor a lack of enforcement of those policies; rather, it is inadequate oversight. In other words, the districts are not addressing problems like hazardous materials in the classrooms because they are not performing the oversight necessary to know those problems exist.

In contrast, the districts explained that the overarching cause of the larger maintenance problems we identified is a lack of funding. Many of the deficiencies we observed will likely require significant time, investment, and specialized work to correct, which could be costly. For example, we noted 11 schools with nonfunctioning drinking fountains, which could require plumbing work. In addition, 14 of the schools we visited had evident roof problems that will likely require repair or replacement, and we observed stained ceiling tiles at all 18 schools, suggesting the possible need for even more roof work. Even a seemingly easy deficiency to fix, like daisy-chained power strips, may require significant expense to rectify: if a school’s computer room does not have adequate power receptacles, that school will likely need to upgrade its electrical system.

The existence of maintenance and safety deficiencies increases risks to students and staff and can negatively affect educational outcomes. Throughout the pages that follow, we provide examples of the kinds of deficiencies that led to our assigning low scores to the schools we reviewed. Appendix A includes the school-reported scores on the SARC and the generally lower scores we calculated according to our own observations, for each of the 18 schools we visited.

Each of the 18 Schools We Inspected Had Safety Deficiencies

To satisfy the Good Repair Standards of the FIT, schools must properly store hazardous materials that may pose a threat to students or staff in locked containers or in areas that students cannot access. Table 3 breaks down the Safety scores for the schools we inspected. Failure to store hazardous materials as required results in a deficiency or an extreme deficiency, depending on the severity of the risk. For example, improperly stored hazardous chemicals and flammable materials could indicate an extreme deficiency. A deficiency is warranted when, for example, a school improperly stores aerosols or pesticides.

Of the 983 rooms we reviewed across the 18 schools, 359 had hazardous materials stored in an unsecured manner. The hazardous materials we identified included chemicals such as cleaning supplies, as Figure 5 shows. We also observed insect poisons. In one example, Palo Verde Unified had distributed a particular hazardous cleaning product to all of the schools we inspected, and that product was present in 51 classrooms. According to the manufacturer, contact with this cleaning product can cause irreparable eye damage, skin corrosion, and other serious conditions. When we informed the district of this hazard, it immediately removed the cleaning product, and it was not present upon a reinspection.

Figure 5

Unsecured Hazardous Materials Were a Significant Source of Deficiencies at Each of the Schools

Source: Auditor observation at Calaveras Unified, Palo Verde Unified, and Los Angeles Unified.

Note: Deficiencies in this FIT section, such as those used as examples above, included hazardous supplies that we found in unlocked areas and containers.

Figure 5 is titled “Unsecured Hazardous Materials Were a Significant Source of Deficiencies at Each of the Schools.” The figure includes six pictures. The first picture shows a bottle of cleaning agent called “Re-Juv-Nal.” The caption reads We observed cleaning solutions like this one in classrooms throughout a district. The Material Safety Data Sheet for this product indicates that it is flammable and that contact with it causes irreversible eye damage and skin burns.” The second picture shows three containers of cleaning solutions. The caption reads “This cleaning solution, seen here in an elementary school, was found throughout classrooms in another district. It can cause serious skin corrosion and eye damage.” The third picture shows several gas canisters. The caption reads “These canisters of pressurized gas were unsecured in an auto shop classroom at a high school. Unsecured pressurized canisters can become dangerous projectiles if the valve is dislodged.” The fourth picture shows eight containers of various cleaning solutions in an under-sink cabinet. The caption reads “Ajax cleaning powder, cleaning chemicals, and an unlabeled spray bottle were in an elementary school classroom. Such supplies can cause chemical burns as well as skin and lung irritation.” The fifth picture shows a large bottle of a substance called “OdoBan.” The caption reads “This cleaning solution was in a middle school classroom. The product’s Material Safety Data Sheet indicates that it causes serious eye irritation, and may cause respiratory irritation.” The final picture shows a spray can of Lysol. The caption reads “Aerosol sprays were also found in numerous classrooms across all districts. The Material Safety Data Sheet for this product indicates that it is flammable and can irritate the lungs and skin.” The source for these photographs is auditor observation at Calaveras Unified, Palo Verde Unified, and Los Angeles Unified. The figure ends with the following note: Deficiencies in this FIT section, such as those used as examples above, included hazardous supplies that we found in unlocked areas and containers.

Although the districts consistently corrected the safety hazards we identified, their presence in so many classrooms raises concerns about what may be occurring at other schools throughout the State. For example, staff at several of the districts we reviewed informed us that teachers bring in their own cleaning supplies, despite being directed not to do so. Hazardous chemicals require careful and knowledgeable use, and storing them in an unsecured manner increases the risk of health consequences to students. When elementary school students, for example, have access to toxic cleaners—as they did at all of the eight elementary schools we reviewed—the risk to their safety requires immediate action. The photo shows an example of a hazardous material we observed.

We observed this cleaning chemical in a kindergarten classroom at Ruth Brown Elementary School and in other classrooms throughout Palo Verde Unified.

Source: Auditor observation.

In addition, researchers have determined that health and safety risks often correlate with weaker academic performance. The 21st Century School Fund measured the relationship between Los Angeles Unified school sites’ compliance with the district’s health and safety regulations and those sites’ academic performance.7 The study concluded that schools with the highest levels of compliance had 36 percent higher test scores than schools at the lower end of the compliance spectrum. The FIT’s health and safety standards overlap with the health and safety regulations measured in this study.

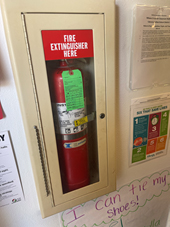

In addition to unsecured chemical hazards, we also identified fire safety deficiencies at all of the schools we inspected. The risks arising from fire safety deficiencies are clear: they may cause fires or limit the ability to respond effectively to fire‑related emergencies. Not only can fire and smoke cause bodily harm, they can also damage facilities to such a degree that students’ educations are negatively affected.

Despite the importance of fire safety, deficiencies contributed to poor scores for Safety at 14 of the 18 schools we reviewed. For instance, four schools—one each in Calaveras Unified, Chico Unified, Palo Verde Unified, and Los Angeles Unified—had barbeques and propane tanks located inside of classrooms. According to state regulations, schools should store propane tanks—which are filled with flammable gas—in a location away from external heat sources and combustible materials, such as, in locked storage units outdoors, as retailers do. Moreover, these tanks should be protected from tampering by unauthorized persons.

Our inspections of the 18 schools also identified over 120 instances of obstructed fire extinguishers, missing fire extinguishers, and fire extinguishers without the gauges necessary to ensure that they are properly charged. The photo provides an example of an obstructed extinguisher. The number of problems we identified with fire extinguishers at the schools we inspected raises concerns about the possible existence of similar problems at schools statewide.

We observed this fire extinguisher locked behind glass but with no method to readily access it in a classroom in Jenny Lind Elementary School.

Source: Auditor observation.

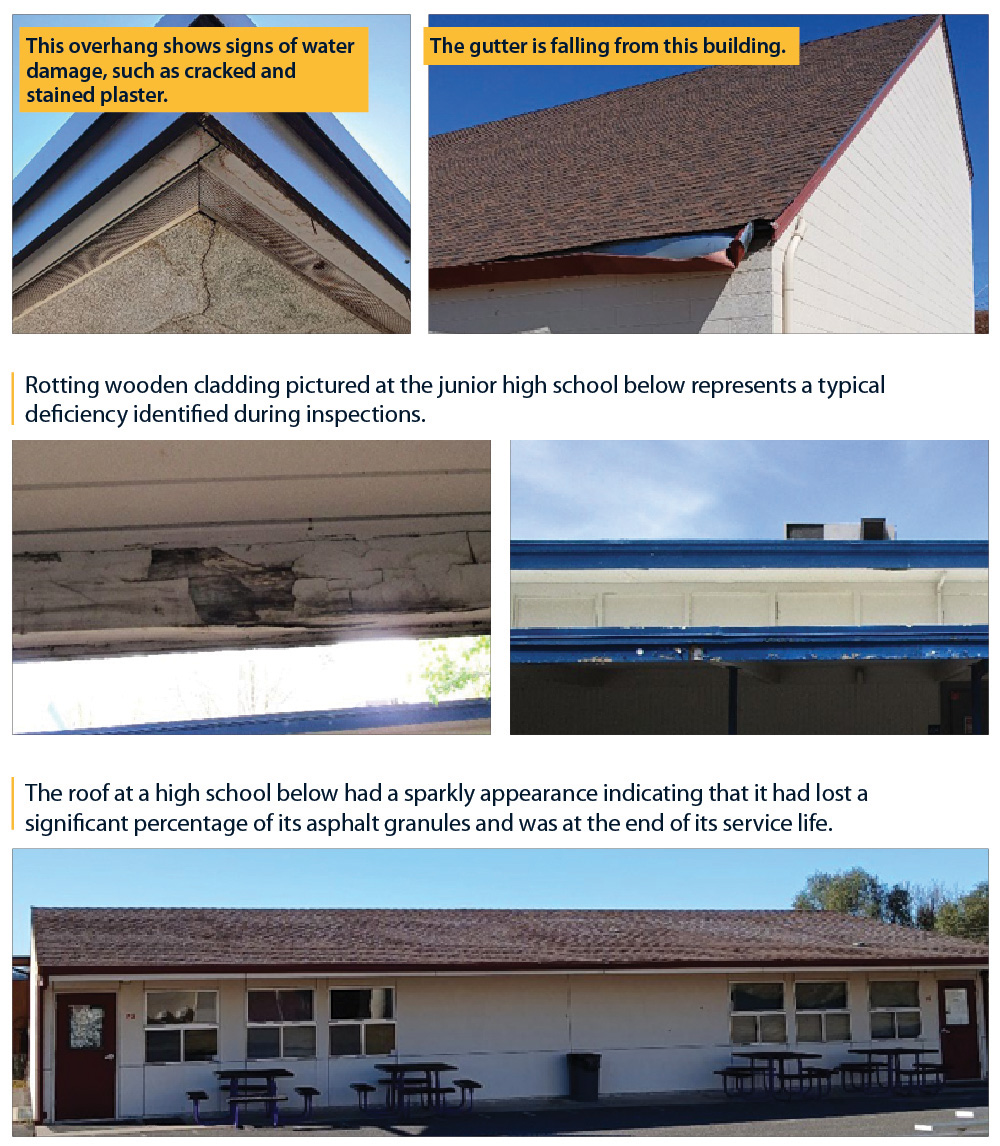

Many of the Schools We Inspected Had Roof Deficiencies

Failing roofs can lead to a cascade of negative consequences. For example, roof leaks can cause water damage, mold, and mildew, all of which can require expensive remediation. Further, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has concluded that mold and mildew can negatively affect students’ health, which may in turn increase their absences and lower their test scores. Table 4 provides a breakdown of the Structural scores we assigned to the schools we inspected.

Nonetheless, we noted deficiencies with the roofs at 14 of the schools we visited. Those deficiencies, when sufficiently frequent, contributed to lower scores for a number of schools in the Structural category, as noted in Table 4. Figure 6 provides examples of some of these deficiencies. According to the FIT, roofs, gutters, and downspouts should appear to be functioning properly and not have visible damage. Many classrooms we inspected had water-damaged ceiling tiles that school staff told us could be the result of leaking roofs. The photo provides an example. Further, four schools, including Calaveras High School, had roofs that were visibly sparkling, indicating that the asphalt granules had worn off and that the roofs needed to be replaced. Asphalt granules are necessary to protect the watertight components of a shingle, and a lack of granules means that the roof is at the end of its life. School officials generally indicated that they were aware that the roofs required replacement but that sufficient funding was unavailable to address such major maintenance items.

We observed stained ceiling tiles like these in a classroom at Citrus Elementary School. Such stains can indicate roof problems.

Source: Auditor observation.

Figure 6

The Schools We Inspected Had Numerous Deficiencies in the Roof Section of the FIT

Source: Auditor observation at Calaveras Unified and Chico Unified.

Figure 6 is titled “The Schools We Inspected Had Numerous Deficiencies in the Roof Section of the FIT.” The figure includes five photographs. In the first, a roof overhang shows signs of water damage, such as cracked and stained plaster. In the second, a gutter is falling from the edge of a roof on a building. In the third and fourth, there are examples of rotting wooden cladding at a junior high school. It represents a typical deficiency identified during inspections. The final photo is of a long one story building. The caption reads “The roof at a high school below had a sparkly appearance, indicating that it had lost a significant percentage of its asphalt granules and was at the end of its service life.” The figure is sourced to auditor observation at Calaveras Unified and Chico Unified.

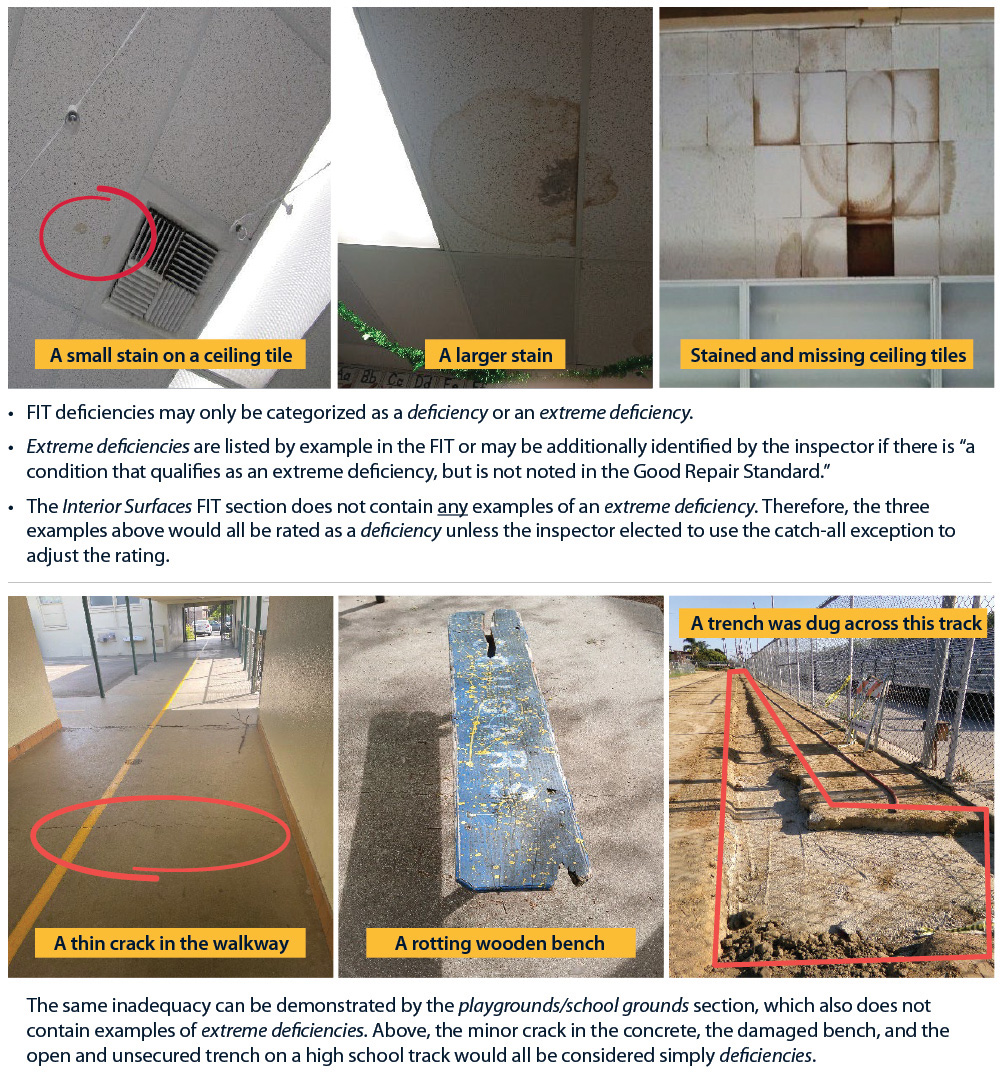

Each of the 18 Schools We Inspected Had Interior Surface Deficiencies

The FIT specifies that to satisfy the relevant Good Repair Standards, interior surfaces such as floors, ceilings, and window casings must appear clean, safe, and functional. Examples of deficiencies include torn or worn carpeting, water damage, and tears in walls, as the text box describes. These types of damaged interior surfaces can increase risk by exposing students and staff to mold and by creating tripping hazards, among other concerns. Studies have shown that attending schools with poorly maintained facilities, such as deteriorated interior surfaces, can negatively affect students’ educational outcomes. All 18 schools we inspected had interior surface deficiencies that resulted in our assigning them a poor score in that category and section, as Table 5 shows.

Interior Surface Deficiencies, According to the FIT Guidebook

Ceilings

- Cracks, tears, holes, or water damage.

- Missing, damaged, loose, or stained ceiling tiles.

- Mildew or visible mold.

Walls

- Cracks, tears, holes, or water damage.

- Missing, damaged, or loose wall tiles.

- Damaged plaster or paint.

Flooring

- Cracks, tears, holes, or water damage.

- Missing, damaged, or loose floor tiles.

- Damaged or stained carpets.

Source: The FIT Guidebook, California Coalition For Adequate School Housing, October 2017.

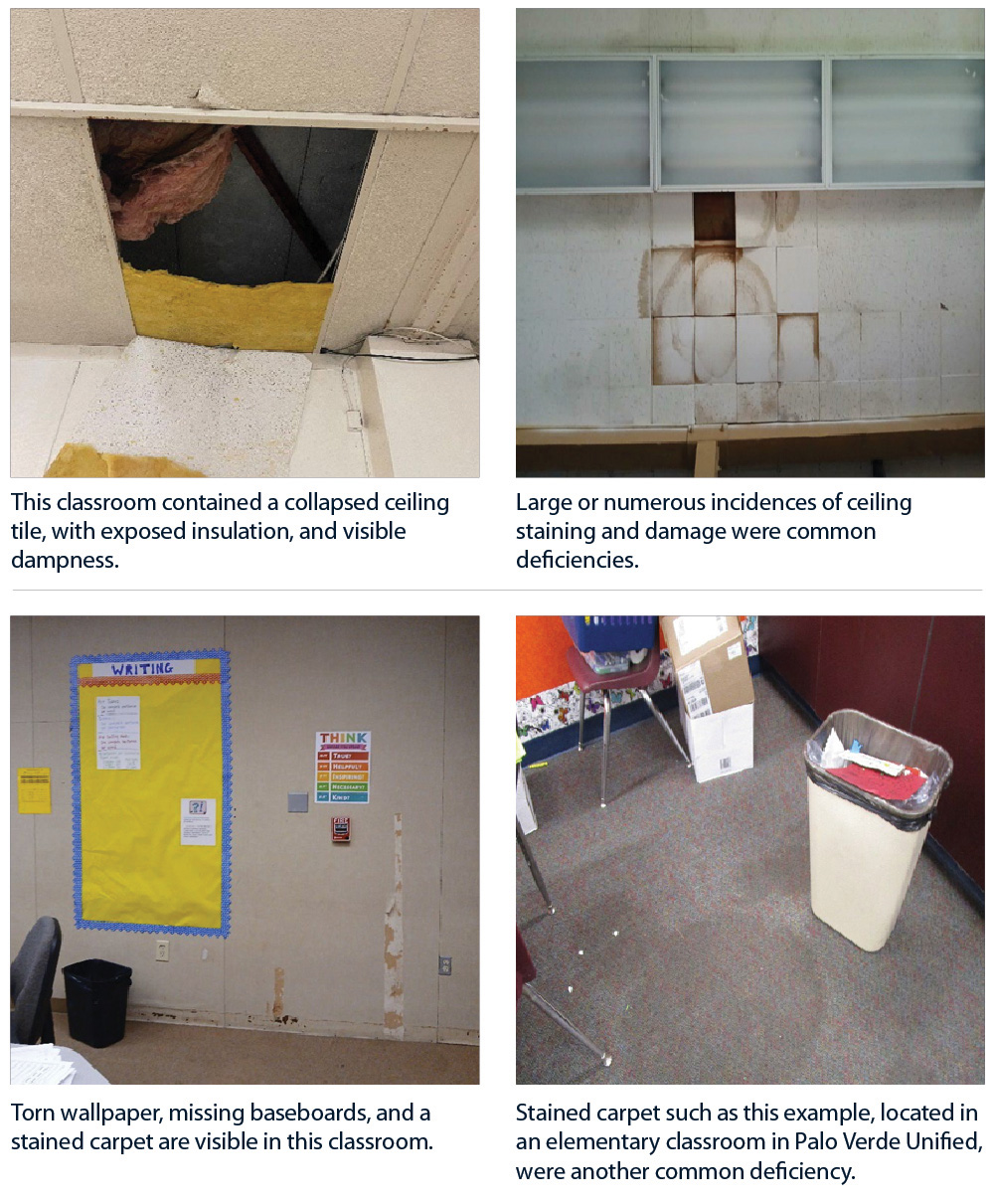

Further, many classrooms had multiple deficiencies in the Interior Surfaces category. For example, 34 of 48 classrooms we inspected at Palo Verde High School in Palo Verde Unified had stained or damaged ceiling tiles, damaged walls, damaged floors, or a combination of these. Similarly, Citrus Elementary School in Chico Unified had 18 classrooms with multiple Interior deficiencies, such as stained or moldy ceiling tiles and damaged linoleum floors. Figure 7 provides examples of these types of deficiencies. Schools generally reported that such deficiencies were the result of a lack of adequate funding to perform needed maintenance.

Figure 7

We Assigned Poor Ratings for the Interior Category at Each of the Schools We Inspected

Source: Auditor observation at Calaveras Unified and Palo Verde Unified.

Figure 7 is titled “We Assigned Poor Ratings for the Interior Category at Each of the Schools We Inspected.” The figure contains four photographs. In the first, a ceiling tile is missing, exposing yellow and pink insulation. The caption reads: “This classroom contained a collapsed ceiling tile, with exposed insulation, and visible dampness.” The second photograph shows numerous brown-stained ceiling tiles next to a long light fixture. One of the tiles is missing. The caption reads: “Large or numerous incidences of ceiling staining and damage were common deficiencies.” The third photograph shows a wall with several posters on it. A section of the wallpaper is torn away and the baseboards are missing. The caption reads: “Torn wallpaper, missing baseboards, and a stained carpet are visible in this classroom.” The final picture shows a water-stained carpet. The caption reads “Stained carpet such as this example, located in an elementary classroom in Palo Verde Unified, were another common deficiency.” The source of this figure is auditor observation at Calaveras Unified and Palo Verde Unified.

Three of the 18 Schools We Inspected Had Cleanliness Deficiencies That Resulted in Fair or Poor Scores

Finally, a lack of cleanliness in schools can lead to increased absenteeism. In fact, research has found that students are more likely to attend schools that meet certain staffing standards regarding the number of custodians per square foot.8 The FIT states that school grounds and buildings should appear to have been cleaned regularly, with minimal buildup of dirt and no odors. Table 6 compares our observation of school cleanliness with schools’ reported scores.

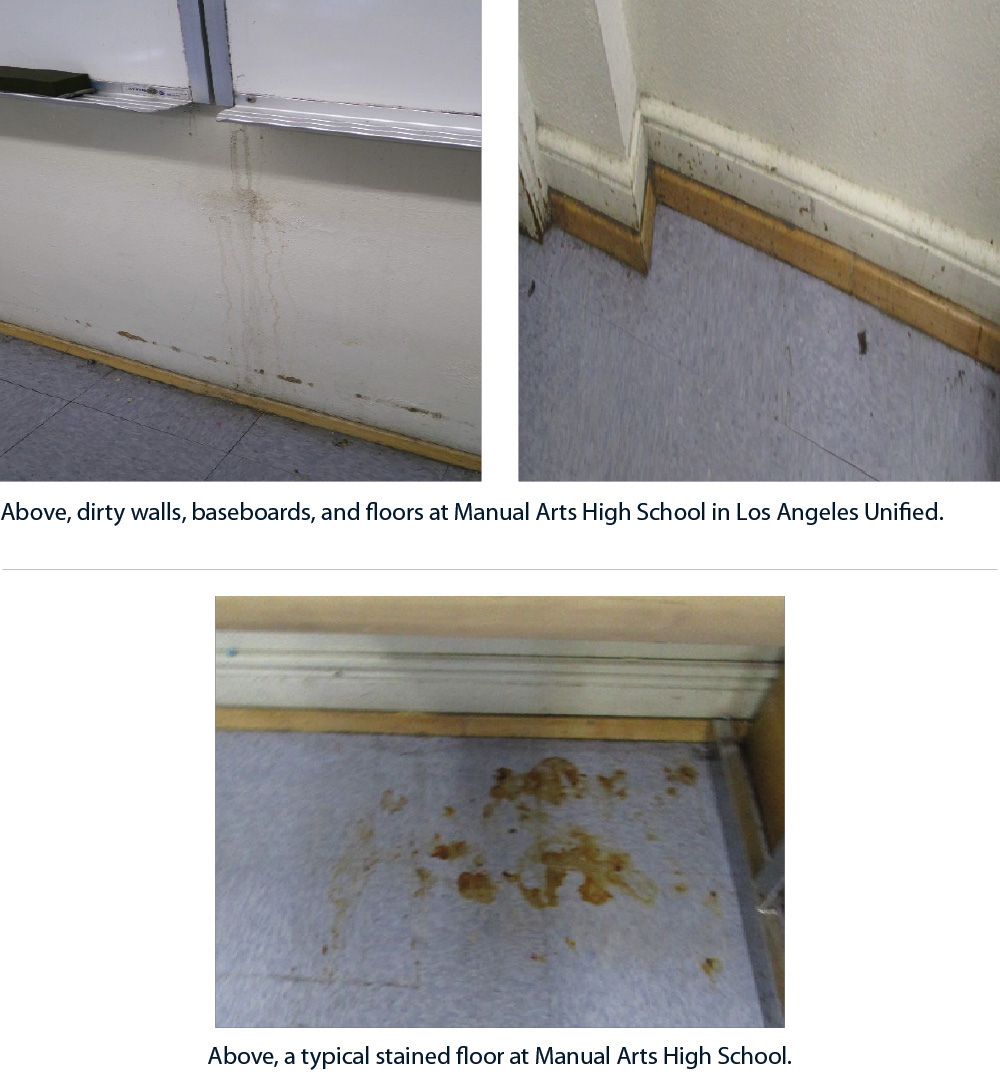

However, we assigned fair or poor scores in Cleanliness to three of the schools that we inspected: Chico Junior High School in Chico Unified, Rudecinda Sepulveda Dodson Middle School and Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles Unified, as Table 6 details. In each of these three schools, our inspection identified numerous deficiencies. For example, 57 of the classrooms we inspected at Manual Arts High School had grime and dust buildup on windowsills, baseboards, and floors. Some walls also appeared to be visibly dirty. Similarly, Chico Junior High School had grimy baseboards and visibly dirty exterior walls. Figure 8 provides examples of the deficiencies we noted at Manual Arts High School.

Figure 8

Manual Arts High School Exhibited Deficiencies in Its FIT Cleanliness Category

Source: Auditor observation of Manual Arts High School.

Figure 8 is titled “Manual Arts High School Exhibited Deficiencies in Its FIT Cleanliness Category.” The figure includes three photographs. The first shows a dirty wall with water stains flowing down from whiteboards and the second shows a corner with grime-covered baseboards. The caption under both reads: “Above, dirty walls, baseboards, and floors at Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles Unified.” The third picture shows brow staining on a linoleum floor in the corner of a room. The caption reads “Above, a typical stained floor at Manual Arts High School.” The source for this figure is auditor observation of Manual Arts High School.

We observed custodians cleaning at all three school sites. However, the cleaning deficiencies appeared long-standing in nature: for example, we found grime that was difficult to remove manually. School leadership at Manual Arts High School indicated that even though staff cleaned the school over the summer, some areas will look dirty because the school is old. The principal at Chico Junior High School noted that his leadership team pressure-washes the school exterior regularly but that the school’s layout—consisting of dirt patches next to walkways—means that the exterior surfaces are often visibly dirty again within days. Both of these are logical rationales for the observed deficiencies. Nevertheless, the conditions are not clean.

In addition, we determined that Manual Arts High School and Rudecinda Sepulveda Dodson Middle School in Los Angeles Unified—along with Chico Junior High School and Pleasant Valley High School in Chico Unified—have not maintained sufficient custodial staffing to meet federal recommendations. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES)—a federal agency that is part of the U.S. Department of Education—publishes cleaning standards, including custodial staffing benchmarks, in their best practice guidelines for school facilities. The NCES estimates that one custodian should be able to clean from 19,000 to 25,000 square feet per eight-hour shift while maintaining a standard that will ensure the health and comfort of students and staff. Our analysis indicates that the four schools we list above have assigned custodians to clean more than 25,000 square feet since academic year 2014–15, as Table 7 shows. Chico Unified staff noted that the custodial staffing records for our selected schools do not include substitute or roving custodians, which the district assigns to schools temporarily and on an as‑needed basis. However, despite these staffing ratios, we found only one of the four schools to be poor in the Cleanliness category.

Calaveras Unified, Fresno Unified, Palo Verde Unified, and Santa Maria-Bonita generally assigned their custodians areas to clean that fell within NCES’s best practices. Specifically, since academic year 2014–15, four of the 15 selected schools with data back to academic year 2014–15 increased the square footage they assigned per custodian, four schools did not change the assigned square footage, and seven decreased it. Perhaps as an effect of the current square footage assignments, very few of the schools we reviewed exhibited cleanliness problems. We provide additional information on custodial staffing levels in the Other Areas We Reviewed section of this report.

Under the LCFF, School Maintenance Competes With Other Priorities for Funding

The competing priorities schools face when allocating their resources, in part because of the elimination of a dedicated funding stream for maintenance, have likely contributed to the maintenance deficiencies we observed. A funding stream dedicated to a particular purpose is called categorical funding. For example, before fiscal year 2013–14, schools received deferred maintenance funding from the State, which provided $313 million to schools in fiscal year 2012–13. Indeed, school districts told us that maintenance often depends on the availability of funds. Since fiscal year 2013–14, school districts have received state resources through the LCFF. School districts receive LCFF resources through a formula that is based on average daily attendance in each grade, and that formula includes additional funding to support students who are English language learners, eligible for free or reduced price meals, or who are foster youth. According to the Brookings Institute, the LCFF sought to increase equity, efficiency, and flexibility in school funding by replacing categorical funding streams—that also included complicated formulas and spending restrictions—with unrestricted state aid that districts can use according to local needs and priorities.

However, the LCFF does not include funding earmarked for building maintenance in its formula, and state funding for maintenance outside of the LCFF is minimal. As noted above, the LCFF is based on attendance and certain characteristics of students in districts; it does not include factors associated with facilities. Further, funds dispersed through the LCFF comprise the majority of funds that districts receive. According to the Public Policy Institute of California, the State’s funding constitutes the majority of funding for schools, more than 60 percent in recent years. The remainder comes primarily from local sources. Among the six districts we visited, LCFF accounted for between 50 and 85 percent of the districts’ budgets.

We found several other opportunities for maintenance funding, but they had significant limitations on both the use of funds and the amount of funding available. One such program is the California Schools Healthy Air, Plumbing, and Efficiency (CalSHAPE) Program. Funded with proceeds from California’s large electric and gas investor-owned utilities, the program is available to local education agencies throughout the State who seek to assess, maintain, and upgrade their ventilation and plumbing systems. Unfortunately, these funds would only be applicable to one of the eight facilities categories reported in the SARC: the Systems category. Further, the program paused accepting applications after July 2024, citing concerns over funding availability and project completion timelines because all unused funds must be returned to the utilities by December of 2026. We found that 15 of the 18 schools we reviewed—all the schools we reviewed except for those in Los Angeles Unified—were awarded a total of more than $3 million in funding for plumbing or ventilation from the program, as of the July 2024 award list.

Another program is the California Energy Commission’s (CEC) Energy Conservation Assistance Act-Educational Subaccount (ECAA-Ed) Zero-Interest Loan Program. Also available to local education entities across the State, ECAA-Ed funds could apply to a limited selection of SARC maintenance categories: the Systems and Electrical categories, particularly to upgrade lighting, heating, and ventilation systems. ECAA‑Ed funds are composed of revolving loan funds, meaning they are replenished as borrowers repay them. CEC notes that the program has been oversubscribed, and because it does not have dispersible funds until it receives loan repayments, CEC is placing all new applications on a waiting list. Of the districts we reviewed, only Chico Unified received funds from this program in the last decade.

Finally, school districts and the State can and have proposed bonds for voter approval that may provide funding for school facilities. For example, in 2016 voters in Fresno County approved $225 million in bonds for improving educational and support facilities within Fresno Unified. In November, California voters supported a measure (Proposition 2) to raise $10 billion in bond funds for school and community college classroom upgrades, including $4 billion for the renovation of existing buildings and $3.3 billion for new construction. This ballot measure—for which final results are expected to be certified in December—is in line with a 2022 State Auditor report that estimated schools would need at least $7.4 billion to meet school district modernization funding requests through 2027 alone, and modernization does not address all elements to keep a school in good repair.9 Further, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO), the measure requires school districts to provide between 35 and 45 percent of the funding for construction and renovation. Thus, school districts without the funding to set aside for these projects could be at a disadvantage.

The six school districts we reviewed spent significantly different amounts on custodial staff and maintenance. For all school districts that receive specific state funds related to the construction, modernization, reconstruction, alteration of, or addition to school buildings, state law requires those districts to set aside 3 percent of their general fund expenditures each year for maintenance. All six districts reported meeting that requirement. All six districts also stated that 3 percent was not sufficient to cover their maintenance costs. Further, during the period we reviewed—fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23—five of the districts increased their spending for the budget category “physical plant,” which represents the activities necessary to maintain and operate the facilities. The increases for Calaveras Unified, Chico Unified, and Los Angeles Unified ranged from 4.9 percent to 17 percent. Fresno Unified increased its funding by 52 percent, while Santa Maria-Bonita increased maintenance-related funding by 62 percent, in large part because it chose to direct pandemic relief funding to maintenance.

The remaining district, Palo Verde Unified, reported a decrease in its maintenance expenditures between academic years 2021–22 and 2022–23, by 21 percent. However, the district’s academic year 2023–24 budget shows that the district plans to double its expenditures on plant services—the budget area that includes facilities maintenance. According to the district, this budget includes significant projected expenditures from one-time funds related to a delayed shade structure project across school sites, additional security personnel and training, and planned heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) system improvements.

Despite these increases in funding and one-time investments, schools in most of the districts contained two or more FIT categories that our inspections scored as poor, often related to Interior Surfaces and Roofs. However, FIT scores were higher at school districts that had additional funding to dedicate to maintenance. For example, our inspections gave Santa Maria-Bonita’s schools the highest overall scores of any of the schools we reviewed, in part as a result of the district’s investment of pandemic relief funds in maintenance. Fresno Unified increased its maintenance spending by 52 percent during the years we reviewed, which contributed to positive maintenance outcomes: two of its schools received overall good scores from our inspections.

Further, schools that received increased LCFF funding also had higher FIT scores. Under the LCFF, districts receive additional funding if their enrollment of English learners, free and reduced price lunch recipients, and foster youth exceeds 55 percent of total enrollment. Our inspections found that these same schools tended to have higher FIT scores. In fact, the three schools that our inspections identified as having the highest overall scores had student populations in which more than 90 percent of students were in categories that receive additional support. These results suggest that additional funding, dedicated to maintenance, would make a positive difference in FIT scores.

Officials at each of the school districts we spoke with stated that obtaining sufficient funding for maintenance was a continual challenge. The districts stated that the lack of dedicated funds, as well as tight budgets overall, meant that the districts often deferred maintenance in favor of other competing priorities. Fresno Unified was able to quantify the scope of its needs. A consultant that the district hired conducted a maintenance study that found the district would need to spend $2.49 billion to return its school sites to an “80 percent” maintenance standard. This standard means the schools would still have outstanding maintenance issues. For context, Fresno Unified’s total general fund revenue for fiscal year 2023–24 was just over $1.7 billion.

Even with Proposition 2 funding, current State budget pressures will continue to require that school districts make choices regarding where to target limited funds. Kindergarten through grade 12 education represents $82 billion of California’s $212 billion general fund budget for fiscal year 2024–25. In February 2024, the LAO estimated the State would face a $73 billion budget shortfall for the 2024–25 fiscal year. Although the enacted budget addresses this shortfall, the LAO estimates continued deficits in the years to come. Given that K-12 education makes up nearly 40 percent of the State’s general fund, schools will likely continue to face budget pressure.

In addition, public school enrollment has fallen in recent years, which could reduce school budgets. The State’s public schools have seen enrollment decrease by 368,000, or six percent, since academic year 2017–18. Table 8 shows enrollment statewide and at the school districts we reviewed. Because school attendance is a factor in calculating how the State distributes education funds, schools with significant decreases in enrollment may also receive a smaller share of state funding. For example, Los Angeles Unified’s enrollment fell by 78,000 students—or about 17 percent—from academic year 2018–19 to academic year 2022–23. The other districts we reviewed have faced less severe enrollment declines, ranging from nearly 1 percent to 6.4 percent. Calaveras Unified’s enrollment increased slightly—by 1 percent—but it experienced the greatest decline of all districts during the 2020–21 school year, over 6 percent.

School districts have so far been able to generally increase budgets for both classified staff—such as custodians, staff, and personnel in school administration—and certificated staff—those with a teaching credential. Only Fresno Unified increased funding for classified staff and decreased it for certificated staff. Table 9 presents the classified and certificated staff budgets for the districts we reviewed. However, without additional dedicated funding for school maintenance, school districts may need to choose in the future between funding increasingly severe maintenance deficiencies and funding student learning, which is likely to be a difficult choice given how deeply the two are interrelated.

Without Effective Oversight, School Facilities Will Remain in Poor Condition

Key Points

- The 18 schools in our review reported FIT scores in their SARCs that were significantly higher than the scores our inspection supported.

- County offices of education have oversight responsibilities related to ensuring the cleanliness, maintenance, and safety of Williams schools, and one of the ways they have not fulfilled those responsibilities is by not ensuring the accuracy of the schools’ FIT reporting.

- The schools we visited appropriately posted information about the Williams complaint process and resolved the substantiated complaints about maintenance or cleanliness that they received. However, most of the schools we reviewed rarely, if ever, received Williams complaints regarding maintenance and cleanliness, despite the deficiencies we identified at their facilities.

Our Inspections Indicate That the SARC Scores for All 18 Schools We Visited Included Higher FIT Scores Than Conditions Warranted

All 18 schools we reviewed across six districts reported higher FIT scores than our inspections supported. On average, schools scored themselves about one score higher overall. For example, Rudecinda Sepulveda Dodson Middle School and Manual Arts High School, both in Los Angeles Unified, reported overall scores of exemplary in their SARCs. However, when we calculated those schools’ scores according to our observations, we rated them poor overall. Seven of the other schools we inspected reported overall scores of good, while we rated them fair or poor. Appendix A provides further detail on district scores and our scores, by school.

School officials generally asserted that the discrepancies between their scores and ours were the result of the timing of the inspections. Maintenance directors at several of the school districts we inspected stated that they conduct their FIT inspections during winter or summer breaks, when custodial staff conduct additional deep cleaning. However, we conducted our inspections in the spring and after school hours. Because our reviews occurred after class when school was in session and children were still on site, our inspections present a more realistic view of a school’s day-to-day state; however, it is likely that schools in use will show greater wear and tear. Los Angeles Unified in particular noted that because our inspections of their schools occurred months after the district conducted its inspections, some of the problems we observed could have developed in that interval.

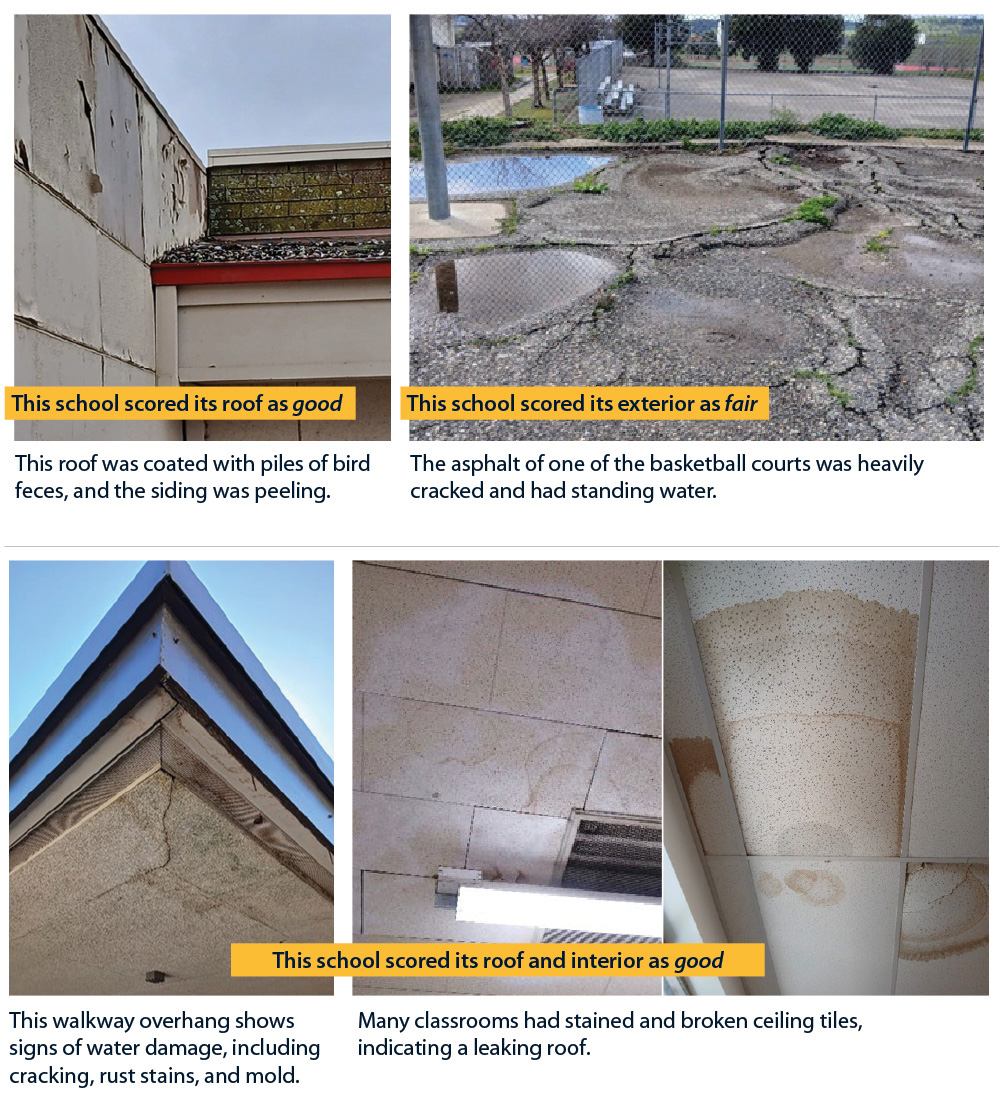

However, some of the problems we noted appeared to be longstanding. For example, Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles Unified had cracked tennis courts and asphalt, a trench dug across the running track, and rusty gutters. These deficiencies are unlikely to have appeared in the span of a few months. At Pleasant Valley High School in Chico Unified, roofs overhanging some walkways were actively dripping, displayed signs of water damage, and had related deficiencies, such as mold and rust. We also observed several roofs that had shiny roof shingles, a sign that the asphalt granules in the shingles have worn away and that the roof needs to be replaced. Figure 9 includes examples of maintenance deficiencies throughout the schools we inspected that likely were problems well before the districts’ most recent inspections or ours.

Figure 9

We Identified Significant Maintenance Deficiencies at Many Schools That Were Not Reflected in Prior Scores

Source: Auditor observation at selected schools.

Figure 9 is titled “We Identified Significant Deficiencies at Many Schools That Were Not Reflected in Prior Scores.” The figure includes five photographs. The first photograph shows a section of roof against a wall. The roof is coated with piles of bird feces. The siding on the building against the roof is peeling. The caption reads “This school scored its roof as good.” The second photograph shows an asphalt basketball court with heavy cracks, pits, and puddles of water. The caption reads “This school scored its exterior as fair.” The third photograph shows a walkway overhang with signs of water damage, including cracking, rust stains, and mold. The fourth and fifth photographs show which ceiling tiles almost entirely covered with brown stains and including some broken tiles, indicating a leaking roof. The bottom three photographs are captioned “This school scored its roof and interior as good.” The figure is sourced as auditor observation at selected schools.

School officials could not provide additional reasons for the discrepancies between their scores and ours; however, schools may have an incentive to rate themselves generously. As part of the SARC, the FIT provides information on schools’ condition to parents, administrators, policymakers, and the public. Thus, school FIT scores can affect a school’s reputation. For example, some parents may use this information in making educational decisions for their children, such as whether to send children to the local school or try to enroll them in a more distant school. The FIT may help inform policymakers’ decisions about where to focus limited maintenance resources, should they choose to use it as such, but as we note previously, the need likely far outweighs available resources.

County Offices of Education Have Not Fulfilled Their Oversight Duties by Accurately Verifying Williams Schools’ FIT Reporting

Seven of the 18 schools we selected for inspection were Williams schools.10 As we discuss in the Introduction, state law requires county offices of education to visit and examine each school in the county—including Williams schools—at reasonable intervals to observe school operations and to learn of school problems. County offices of education are required to visit Williams schools at least annually and determine, among other issues, the state of school facilities, which include their FIT scores. While county offices performed their inspections at different points in the year, we performed our inspections in the spring while school was in session to represent the school’s day-to-day state, which may also show greater wear and tear. We found that although county offices of education conducted facilities inspections at Williams schools, they did not identify the deficiencies that we found during our inspections; only the county’s score for Santa Maria-Bonita matched ours. As Table 10 shows, the other county offices of education rated schools higher than we did, and three schools received higher scores from the county offices of education than from their respective districts.

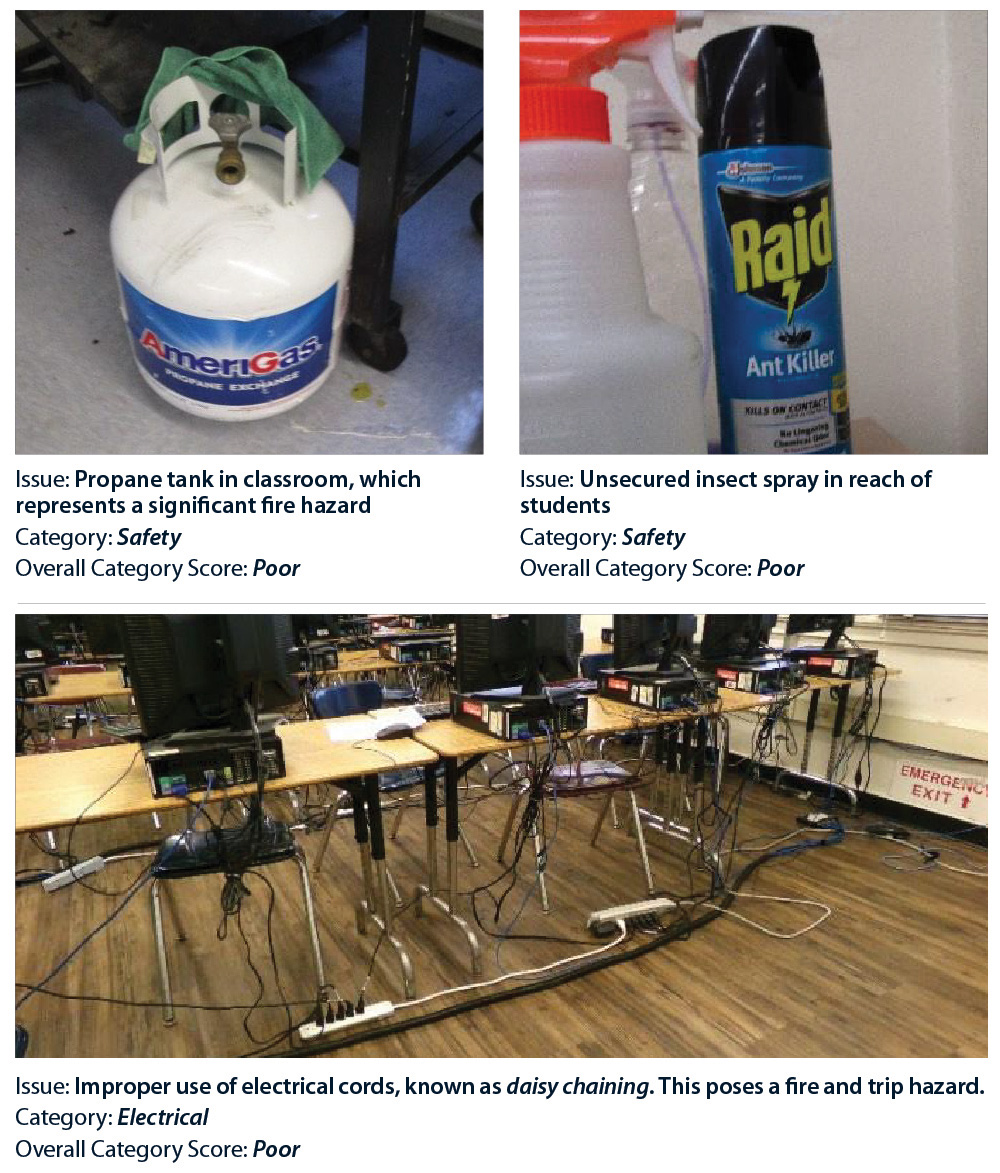

Because the county offices of education are required to determine the accuracy of the data reported by the school districts, we expected that the counties’ scores would closely align with ours. However, as Table 10 shows, that was not the case: two of the six county offices of education—Calaveras and Fresno—reported even higher overall scores for the Williams schools than the schools themselves reported. The Los Angeles County Office of Education’s inspection rated the Manual Arts High School with an overall good score, which was lower than the SARC score of exemplary but higher than our rating of poor. The following year, the county office rated the school exemplary. Figure 10 depicts concerns we identified at the Los Angeles Manual Arts High School that led to our assigning the school a lower score than both the district and the county did.

Figure 10

Our Inspections Identified Deficiencies Not Identified in County Inspection Reports at Manual Arts High School

Source: Auditor observation at Manual Arts High School.

Figure 10 is titled “Our Inspections Identified Deficiencies Not Identified in County Inspection Reports at Manual Arts High School.” The figure has three photographs. The first is a picture of a propane tank. The caption reads “Issue: propane tank in classroom, which represents a significant fire hazard. Category: safety. Overall Category Score: Poor.” The second photograph shows a can of Raid Ant Killer. The caption reads: “Issue: Unsecured insect spray in reach of students. Category: Safety. Overall Category Score: Poor.” The third photograph shows a table with five computers on it. The computers are plugged into power strips that are plugged into each other. The caption reads: “Issue: improper use of electrical cords, known as daisy chaining. This poses a fire and trip hazard. Category: Electrical. Overall Category Score: Poor. The first is sourced as “Auditor observations at Manual Arts High School.”

The Los Angeles county office said that, in general, the FIT captures the conditions of a school as a snapshot in time and may not reflect changes between inspections. The county also suggested that the FIT does not provide a scale that reflects the dynamic severity of a deficiency or the potential degradation of systems nearing the end of their lifecycles. We discuss the limitations of the FIT instrument, including the lack of a scale for severity, in a later section. Nonetheless, many of the deficiencies we identified appear to be longstanding—like uncontrolled water damage over time allowed to penetrate through exterior stucco walls—or frequently repeated—like daisy-chaining power strips when classrooms need additional outlets.

In addition, the Calaveras county office rated the two Williams schools it inspected higher than the schools rated themselves. For example, although the SARC for Jenny Lind Elementary School included an overall FIT score of fair, the Calaveras county office inspection resulted in an overall score of exemplary. In contrast, our inspection resulted in a poor score for the school overall, and we identified several items requiring repair—unlike either the SARC or the county’s inspection—such as damaged roofs, holes in the walls and floors, bowing walls with strong mildew odor, and nonworking sinks and drinking fountains. The Calaveras county office explained that although it uses the FIT during its site inspections, it focuses on documenting what it perceives to be significant safety or maintenance issues; consequently, its inspections may not provide detailed assessments and may result in higher scores. For example, in its 2022–23 FIT inspection of Jenny Lind Elementary School, the county office rated the school exemplary, with a score of 100 percent, regardless of the deficiencies it had noted, such as concrete damage to one of its buildings. We identified similar concrete damage in our inspections. Similarly, in its inspection for Toyon Middle School in the same year, the county’s exemplary score did not reflect its own notes of deficiencies it had found, such as missing ceiling tiles. However, state law requires county offices of education to assess the safety, cleanliness, and adequacy of school facilities, including whether they meet Good Repair Standards, as we have done.

Further, some county offices of education have not been reporting Williams inspections as state law requires. According to state law, county offices of education must report their inspection findings annually to the school boards in their jurisdictions, to the county boards of education, and to the boards of supervisors for each county. State law also requires that county offices of education make quarterly reports to the school boards, describing the inspections they made that quarter and the accuracy of the schools’ related SARCs, even when they performed no reviews during that quarter. However, as Table 11 shows, three of the six county offices of education we reviewed—Los Angeles, Riverside, and Santa Barbara—provided all required Williams reporting.

Butte, Calaveras, and Fresno demonstrated partial compliance in submitting reports. For example, the Fresno county office reported annually to the County Board of Education and County Board of Supervisors, but it stated it does not present a report to each district’s governing board; instead, the Fresno county office stated that the reports are available because they are public. Calaveras did not consistently make annual reports to the district board or County Board of Supervisors but instead made reports to the schools only. The remaining office—Butte—demonstrated that it submits annual reports as required, but its quarterly reporting to the school district governing board did not include SARC verifications or facilities conditions. Without adequate and timely reporting to school boards, county boards of education, and county boards of supervisors, these governing bodies may not have the information they need to make informed decisions on actions—such as budget allocations or work priorities—necessary to ensure the schools are in good repair.

The Williams Complaint Process Has Not Resulted in Districts Effectively Identifying Maintenance Deficiencies at the Schools We Reviewed

The schools we inspected have received few facilities-related Williams complaints. Following the settlement of the Williams case, the Legislature revised state law to require that districts post notices in classrooms—notices we routinely observed during our inspections—explaining how to obtain and file a complaint form and detailing the types of matters subject to the Williams complaint process. However, Table 12, which provides a breakdown of facilities-related Williams complaints at each of our selected districts, demonstrates that all six districts received an average of less than one such complaint per school site per year. One district—Chico Unified—had received none since academic year 2004–05. Districts use the Williams complaint process in part to identify and resolve deficiencies related to emergency or urgent facilities conditions that pose a threat to the health and safety of students or staff. Consequently, the absence of complaints and our own observations indicate that students and staff at school sites are not reporting deficiencies with sufficient frequency to ensure that the schools address the deficiencies. Thus, the Williams complaint process by itself is not an effective means of identifying and addressing school maintenance problems.

Nonetheless, when the schools we reviewed received Williams complaints related to maintenance problems, the schools generally handled those complaints effectively. Under state law, schools must remedy valid complaints within a reasonable time, not exceeding 30 working days from when schools received the complaint. Los Angeles Unified—the largest district in the State—reported having receiving more than 2,900 facilities-related Williams complaints since academic year 2013–14, and many of those complaints were related to air-conditioning systems. We reviewed a sample of 11 of these complaints—one from each fiscal year and all Williams complaints from our remaining selected schools and districts. We found that the schools remedied Williams complaints and issued resolution letters—a requirement of the process that informs individuals who made the complaints of the resolution to the complaint—within the time frames state law required. For example, district complaint files from Los Angeles Unified indicate that one of its schools remedied and formally responded to a Williams complaint related to deficient air conditioning within five business days, well ahead of the required time frame in state law. In addition, the three other schools we selected that received a Williams complaint during the time frame of our audit remedied complaints and issued resolution letters within the time frames set forth in state law.

The Districts We Reviewed Did Not Conduct Oversight Visits to Schools to Examine Conditions as State Law Requires

The districts we reviewed had limited oversight that was ultimately not effective, according to our observations. State law requires district governing boards to ensure that the SARC for each school is issued annually, and we found SARCs to be available for all schools we reviewed. State law also requires district superintendents, their assistants, or the district’s school board to visit each school in the district at least once each term. During these visits, superintendents or the school board are expected to examine the management, needs, and conditions of each school.

Some districts stated that school board officials visited sites periodically, while others noted different methods for addressing these requirements. For example, Palo Verde Unified stated that the school board president and superintendent walk each site quarterly and share verbal feedback with sites. Similarly, Los Angeles Unified described engaging in visits that focused on data collection and engagement, during which district staff meet with site administrators, like school principals, who can raise issues such as those stemming from the physical needs of the school. Three districts—Calaveras Unified, Fresno Unified, and Santa Maria-Bonita—use third-party consultants to perform annual site inspections with the FIT, and Chico Unified stated that it observes conditions at schools as part of activities conducted throughout the year.

Despite these efforts, the results of our inspections indicate that none of the current systems in place for identifying maintenance problems in schools are functioning well. While districts may be making sure SARCs are available, that information is not useful if schools report scores on the FIT that do not reflect current conditions. Also, county offices of education are not casting a critical eye on FIT scores for schools they oversee, the Williams complaint process results in few identified problems, and district leadership are generally unaware of safety concerns. Without effective monitoring, students, parents, and decision-makers do not have access to accurate information about the quality of school facilities or the risks to student health or academic outcomes.