2023-110: California Department of Public Health

Process Improvements Could Help Reduce Delays in Completing Fetal Death Registrations

Published: February 29, 2024Report Number: 2023-110

February 29, 2024

2023‑110

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the California Department of Public Health’s (CDPH) fetal death and stillbirth registration processes, which included a review of four local registrars in the Contra Costa, Los Angeles, Placer, and Sacramento registration districts. In general, we determined that improvements in the fetal death registration process could help reduce registration delays, and we identified some actions CDPH could take to facilitate these improvements.

According to California state law, when a fetus dies after having reached 20 weeks of uterogestation, the fetal death generally must be registered with the local registrar of births and deaths within eight calendar days of the delivery. However, we found that local registration of fetal deaths in California took an average of three times longer than the legally required eight-day time frame. As part of its responsibility in the registration process, CDPH administers the Fetal Death Registration System (FDRS) that parties involved in the fetal death registration process typically use to gather and review the information required to complete a fetal death certificate. Our audit identified six key steps in the fetal death registration process, and we found that registrations proceed more quickly when hospitals take the lead in starting new fetal death certificate records in FDRS and obtain physician signatures. The Legislature could, therefore, help to reduce some delays in fetal death registrations by requiring hospitals to initiate the process.

We also analyzed the ways in which certain parties, such as funeral homes or physicians, may be compelled to meet required time frames in the certificate issuing process. CDPH does not have specific authority to impose administrative sanctions on physicians and funeral homes that fail to meet these requirements, but there are other state entities—such as the California Department of Consumer Affairs’ Medical Board of California (Medical Board) and the Cemetery and Funeral Bureau (Funeral Bureau)—with express authority to do so. We recommend that the Legislature amend state law to require CDPH to coordinate with relevant licensing entities—such as the Medical Board and Funeral Bureau—to provide data and information on fetal death registration timeliness violations in ways that could allow such entities to investigate and sanction violations.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| CDPH | California Department of Public Health |

| Cal-IVRS | California Integrated Vital Records System |

| EDRS | Electronic Death Registration System |

| FDRS | Fetal Death Registration System |

Summary

Results in Brief

When a mother or family (family) experiences a pregnancy that fails in its late stages, they must face both the wrenching emotional aspects of the loss and some specific administrative steps that the State requires. According to California state law, when a fetus dies after having reached 20 weeks of uterogestation, the fetal death generally must be registered with the local registrar of births and deaths (local registrar) within eight calendar days of the delivery. The local registrar’s responsibility includes ensuring the completeness of the fetal death certificate information, registering the fetal death, and then issuing a permit for disposition of human remains (burial permit). In addition, state law requires the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) to register fetal deaths at the state level as it does for all California vital statistics. Significantly, CDPH’s fetal death registration process occurs after the local registrar’s process, and therefore does not affect the eight‑day requirement or families’ ability to proceed with burial or cremation.

CDPH does, however, have supervisory authority over local registrars to ensure uniform compliance with all vital records requirements, including the timely registration of fetal deaths. As part of this responsibility, CDPH administers the State’s electronic system for registering vital events, which is generally used by parties involved in the fetal death registration process to gather and review fetal death certificate information. For the six years of the registration process that we reviewed for this audit—2017 through 2022—CDPH administered the process in its Fetal Death Registration System (FDRS).1

Our analysis of data from this time period shows that local registration of fetal deaths in California took three times longer, on average, than the eight‑day time frame state law allows. Although the statewide data can show how long it took to register a fetal death, it does not show the specific circumstances that may have caused delays. Therefore, in addition to analyzing detailed FDRS data, we interviewed staff at four local registration districts—Contra Costa, Los Angeles, Placer, and Sacramento—and reviewed 20 cases from each of these registration districts to identify the specific sources and causes of fetal death registration delays. This information led us to identify six key steps in the fetal death registration process and the parties typically involved in each. We then analyzed the average processing times for each step statewide and among our four local registration districts.

We found that the steps that caused the longest delays in the fetal death registration process were those in which funeral homes, hospitals, or coroners created a new fetal death certificate in FDRS, collected and entered into the certificate the required information, and obtained the signature of a physician or coroner before submitting the certificate to the local registrar for approval. We found that the steps that contributed least to delays—steps that only take about three days on average—were those steps in which local registrars reviewed and approved a fetal death certificate and issued a burial permit. For example, it took an average of almost 14 days for responsible parties to start a new death certificate in FDRS and begin the subsequent registration process—nearly twice the time frame allowed for the entire process in state law.

We noted an ambiguity in the process that, if clarified, may help to mitigate one of the earliest delays that tends to occur: state law does not specify the precise sequence of events in the registration process or clearly describe who is responsible for starting a new certificate. For example, although state law assigns responsibility for “preparing” the fetal death certificate to funeral homes, it does not specify which involved party should start the new fetal death certificate in FDRS. We found that when hospital staff started the new certificate in FDRS and began collecting information, the average time to complete a fetal death registration was shorter. For example, from 2017 to 2021, Contra Costa hospitals created 89 percent of the registration district’s new fetal death certificates in FDRS, and the average time to register a fetal death certificate in the district from 2017 to 2022 was only 12 days. Although this average still exceeds the State’s required eight‑day time frame, it is the shortest average processing time for registration of the four local registrars we reviewed, and well under the 2017–2022 statewide average of 26 days. The efficiency in Contra Costa likely occurred because hospital staff are more immediately aware when a fetal death has occurred—compared to funeral home staff—and more likely to have direct access to any required medical information.

Another strategy for shortening the processing time to register fetal death certificates calls for adding a specific functionality to CDPH’s data system: enabling the system to automatically notify parties when a certificate is awaiting their action. Although the system currently notifies users that a certificate has already passed the eight‑day registration time frame, it does not provide an equivalent notification when one user transfers a certificate to another user, such as when a hospital transfers an in‑process fetal death certificate to a funeral home or when a party requests a physician’s or coroner’s signature. Our review found that this limitation likely contributed to delays in registrations among some of the cases we reviewed. Among the 80 fetal death registrations we reviewed, we found at least 35 instances of delays occurring because a hospital, funeral home, or local registrar was potentially unaware that a certificate was awaiting their action. For example, the local registrar in one case in Placer took five days before accessing the certificate for review and then rejecting it. That registrar explained that the office staff likely had not known the certificate was pending review until the funeral home called them. A system that requires staff to depend on notification from other parties is less efficient than an automated notification system.

Finally, CDPH has not regularly used its FDRS data to monitor fetal death registration timeliness, to assess the causes of delays, or to communicate delays to parties involved in the fetal death registration. Although 84 percent of fetal death registrations from 2017 through 2022 exceeded the eight‑day registration time frame established in state law, CDPH only infrequently used its FDRS data to monitor timeliness and intervene. CDPH told us that its Vital Records staff’s priority is to certify fetal death certificates and that previously, when staff had time available outside of those duties, they would review FDRS for registration certificates aged over 30 days and send emails to notify local registrars that the certificates were overdue. CDPH explained that it stopped conducting this type of monitoring and sending those emails in 2020 because of staff limitations related to the pandemic. However, the department could only provide limited evidence that it had sent such emails previously, leaving the extent of its past efforts unclear.

CDPH could take a more active role in meeting its oversight responsibilities by engaging with parties in the local registration process to assess the cause of delays and, when applicable, coordinate with these parties to ensure compliance with registration requirements. For example, CDPH could take additional actions to ensure that hospitals or funeral homes are aware of their responsibilities during the fetal death registration process, and the department could ensure that these parties have access to the data system used to register fetal deaths. In addition, although CDPH does not have authority to impose administrative sanctions on funeral homes or physicians who do not meet their obligations to process fetal death registrations within the State’s required time frames, there are other state entities with the express authority to do so. The Legislature could help facilitate those entities’ oversight by requiring CDPH to provide them with clear and actionable information about delays and their possible sources.

Agency Comments

CDPH agreed with our recommendations and explained that it will strive to facilitate a timelier fetal death registration process among all involved parties.

Introduction

Background

General Activities Required to Register a Fetal Death

Experiencing a fetal death is harrowing and emotionally difficult, and for many mothers and families (family), the administrative process of registering the death can exacerbate its impact. According to California state law, when a fetus dies after having reached 20 weeks of uterogestation, the fetal death generally must be registered with the local registration district within eight calendar days of the delivery. Such registration involves starting a new fetal death certificate, obtaining certain information and signatures, and filing the certificate with the jurisdiction’s local registrar of births and deaths (local registrar). The local registrar’s responsibility involves ensuring the completeness of the fetal death certificate information, registering the fetal death, and issuing a permit for disposition of human remains (burial permit) that allows the family to proceed with final arrangements, typically burial or cremation.

Although state law requires a funeral home to “prepare” the fetal death certificate and register it with the local registrar, these provisions do not mandate which entity—whether hospitals or funeral homes—is responsible for starting the process. In some cases, the hospital where the fetal death occurred will start a new fetal death certificate and enter the necessary medical information into the certificate. Sometimes, the family’s chosen funeral home will be the party to start the new certificate and then work with the hospital where the fetal death occurred to obtain the necessary medical information. In the relatively rare cases in which state law requires a coroner to investigate a fetal death, the coroner is generally the party that starts the new fetal death certificate.2

If a parent should wish to, they may obtain a Certificate of Still Birth in addition to the legally required fetal death certificate. A Certificate of Still Birth is an optional certificate, intended to recognize the process of birth experienced by a mother who gives birth to a stillborn fetus and to offer many bereaved parents some solace and comfort. Under state law, a Certificate of Still Birth does not replace the fetal death certificate, is not proof of live birth, and may not be used for any governmental purpose other than to respond to the request of the parent. A Certificate of Still Birth has no legal effect and serves as a voluntary, symbolic recognition for its recipients. Therefore, the Certificate of Still Birth has no bearing on a family’s ability to obtain a burial permit. Accordingly, our audit focuses only on the legally required process for registering a fetal death and obtaining a burial permit.

CDPH Records All Deaths Statewide, Including Fetal Deaths

After a local registrar registers a fetal death, the registrar forwards the fetal death certificate to the California Department of Public Health (CDPH), which is responsible for registering, maintaining, and issuing certified copies of records of all California births and deaths. CDPH’s website explains that a person can use a certified copy of a death certificate to obtain death benefits, claim insurance proceeds, and notify the federal Social Security Administration of the death, among other legal purposes that are by nature generally less applicable to fetal deaths. It is important to note that CDPH’s process to register a fetal death and issue a certified copy of the certificate occurs after the local registrar has registered the fetal death. CDPH’s process therefore does not delay or affect a family’s ability to proceed with burial or cremation. In fact, by the time CDPH registers a fetal death certificate, the local registrar has generally already issued the burial permit.

CDPH Oversees the Fetal Death Registration Process, but It Does Not Have Disciplinary Authority Over All Parties Required to Participate in That Process

State law grants CDPH supervisory authority over local registrars to ensure uniform compliance with all vital records requirements, including the timely registration of fetal deaths. In requiring this oversight, state law mandates that CDPH maintain a system for fetal death registration, which CDPH administers through the California Integrated Vital Records System (Cal‑IVRS), California’s system for registering vital events. Cal‑IVRS is made up of multiple systems, including the Electronic Death Registration System and the Electronic Birth Registration System (EBRS), the latter of which includes the Fetal Death Registration Module, which is used to register fetal deaths. Before June 2023, fetal deaths were registered using the Fetal Death Registration System (FDRS). Almost all of the fetal deaths that occurred statewide for the six‑year period from 2017 to 2022 that we reviewed—on average about 2,250 per year—were registered electronically using FDRS.3

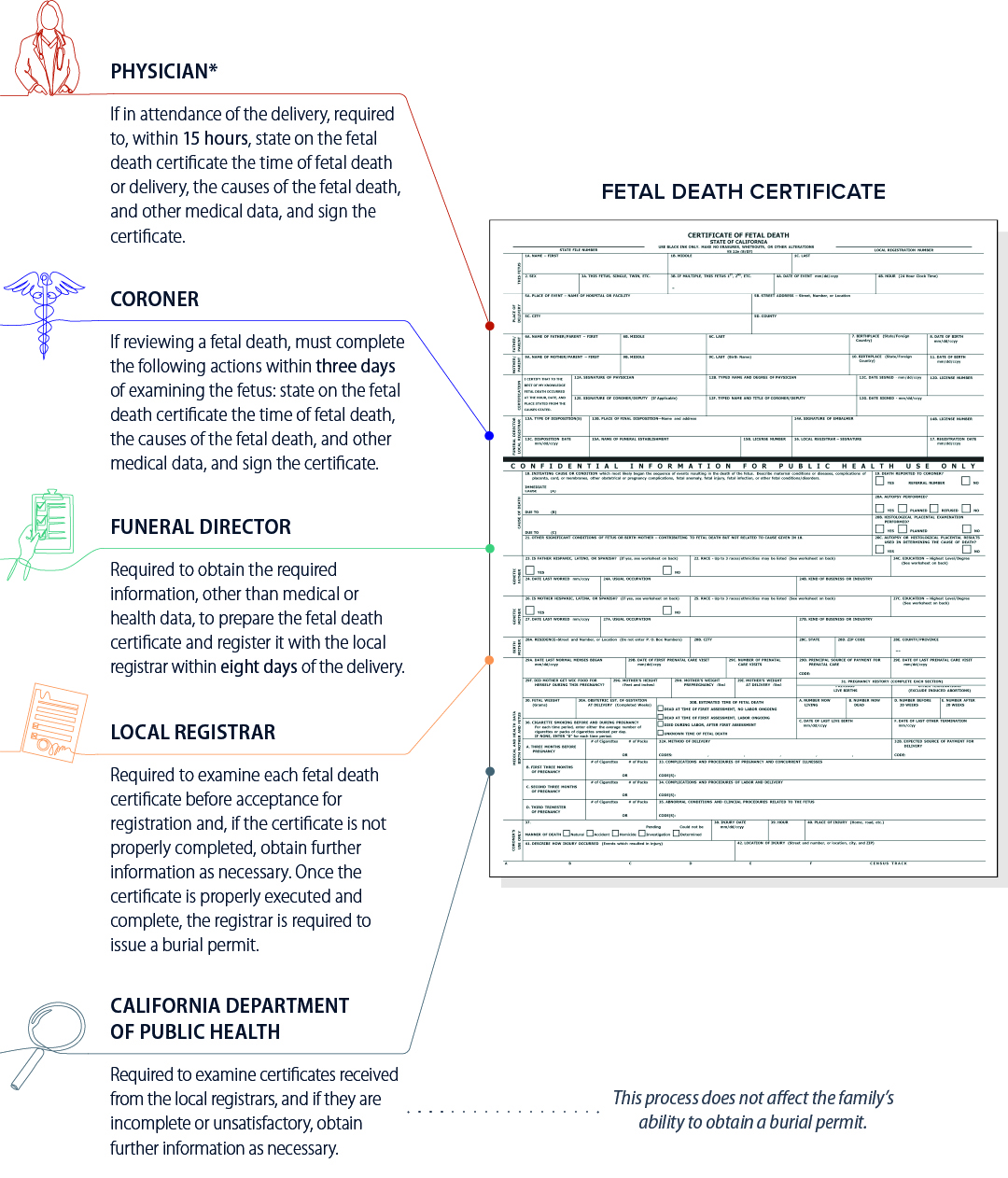

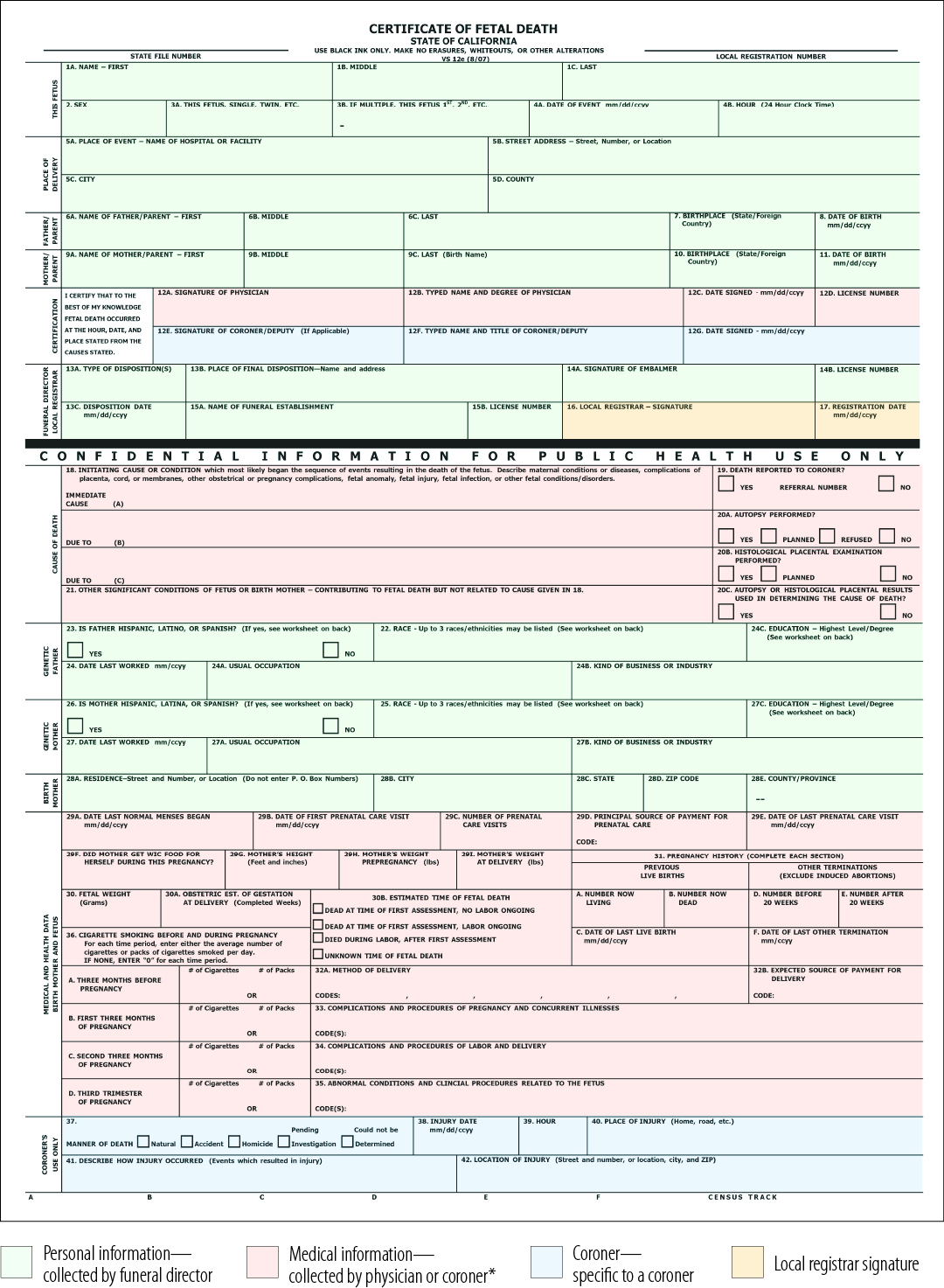

To electronically register a fetal death using FDRS, staff at a local entity—often a hospital or funeral home—first start the process by creating a new fetal death certificate in FDRS, then collect the necessary nonmedical information and, within FDRS, enter that information into the appropriate field on the certificate. Physicians or coroners must enter any required medical information and must sign the certificate before it can be registered. Although CDPH has supervisory authority over local registrars, CDPH does not have the power to impose professional discipline or issue administrative fines to funeral homes, physicians, or coroners for not completing their responsibilities in a timely manner. Figure 1 summarizes each party’s responsibilities under state law during the fetal death registration process. However, although state law outlines some responsibilities for each party during fetal death registration, it neither specifies the precise sequence of events in the registration process nor clearly describes who is responsible for starting a new certificate. The sequence of the actual steps taken by each party varied during the fetal death registrations we reviewed.

Figure 1

State Law Establishes Various Parties’ Responsibilities During the Fetal Death Registration Process

Source: State law.

Note: Figure B in Appendix B shows the types of information required on a fetal death certificate, including the fields that various parties involved in the fetal death registration process are responsible for completing.

*Although state law imposes these requirements on physicians but not hospitals, hospital staff often play a role in completing fetal death certificates and obtaining physicians’ signatures.

Figure 1 Description:

Figure 1 displays a fetal death certificate with various callout boxes describing the responsibilities of various parties under state law during the registration of a fetal death. Physicians, if in attendance of the delivery, are required to, within 15 hours, state on the fetal death certificate the time of fetal death or delivery, the causes of the fetal death and other medical data, and sign the certificate. Coroners, if reviewing a fetal death, must complete the following actions within three days of examining the fetus: state on the fetal death certificate the time of fetal death, the causes of the fetal death and other medical data, and sign the certificate. Funeral directors are required to obtain required information other than medical or health data in order to prepare the fetal death certificate and register it with the local registrar within eight days of the delivery. The local registrar is required to examine each fetal death certificate before acceptance for registration and, if the certificate is not properly completed, obtain further information as necessary. Once the certificate is properly executed and complete, the registrar is require to issue a burial permit. The California Department of Public Health is required to examine certificates received from the local registrars, and if they are incomplete or unsatisfactory, obtain further information as necessary. The California Department of Public Health’s process does not affect the family’s ability to obtain a burial permit. An asterisk on the description of the physician’s responsibilities notes that, although state law imposes these requirements on physicians and not hospitals, hospital staff often play a role in completing fetal death certificates and obtaining physicians signatures. Figure B in Appendix B shows the types of information required on a fetal death certificate, including the fields that various parties involved in the fetal death registration process are responsible for completing.

Statewide, there are 61 local registration districts. Fifty‑eight of these district boundaries generally correspond with California’s 58 counties, and the cities of Berkeley, Long Beach, and Pasadena comprise the remaining three districts. Appendix A shows the number of fetal deaths and the average registration time for each local registration district in the state. We reviewed four local registration districts to assess any differences among them in registration processes and timeliness. The audit request specifically named Sacramento and Placer as two local registration districts for our audit. We also selected the Los Angeles and Contra Costa local registration districts because both registered relatively significant numbers of fetal deaths during the review period, but their average registration processing times differed from one another and from Sacramento and Placer.

Audit Results

Lengthy Processing Times in Registering Fetal Deaths Delay Families’ Receipt of Burial Permits

From 2017 through 2022, the average processing time for registering fetal deaths statewide was three times longer than the eight‑day time frame that state law allows.4 However, CDPH’s data indicates that local registrars’ review and registration of death certificates was not a significant contributor to these delays. Instead, the longest delays occurred in starting a new fetal death certificate, collecting required fetal death certificate information to populate the fields in the new certificate, and in obtaining the signature of a physician or coroner—a step that includes updating medical information if necessary.

Processing Times for Fetal Death Registration Far Exceed Time Frames Allowed in State Law

During calendar years 2017 through 2022, 84 percent of fetal death registrations in California took longer than eight days. Table 1 shows the average and median number of days for fetal death registrations, both of which far exceeded allowable times during those years.

The data also show that the processing time for registering fetal deaths is generally increasing: the average time to register a fetal death increased by 15 percent between 2019 and 2020, by another 20 percent between 2020 and 2021, and it then decreased by 4 percent from 2021 and 2022. We considered whether the fluctuation in registration time could be related, at least in part, to the broader effects of the pandemic. Overall deaths in California increased during the years of the pandemic. CDPH explained that the increase in deaths affected the workload of entities and the timeliness of fetal death registrations, since the same entities who perform death certificate preparation and registration also perform fetal death certificate preparation and registration. In addition, we spoke with staff from the four local registrars we reviewed. Staff from Contra Costa, Placer, and Sacramento told us they had generally not detected much of an impact from the pandemic on the registration process. In contrast, Los Angeles staff reported having received a lot of death certificates in 2020 and 2021 because of the pandemic and asserted that those caused delays in fetal death registrations.

We also spoke with staff at seven hospitals and at eight funeral homes distributed throughout our four local registration districts to obtain their perspective on the fetal death registration process and to identify reasons for delays. Staff at four of the eight funeral homes and six of the seven hospitals told us that the pandemic did not increase the time it took them to register fetal death certificates. Similarly, coroners in three of the local registration districts we reviewed echoed this perspective. However, staff at three of the remaining four funeral homes told us that the pandemic affected how long it took them to obtain the required medical information from hospitals, and the one remaining hospital told us that its staff observed some delays in responsiveness from the local registrar.

We Assessed the Steps and Roles in the Fetal Death Registration Process to Determine Whether Delays in Specific Parts of the Process Drove Statewide Trends

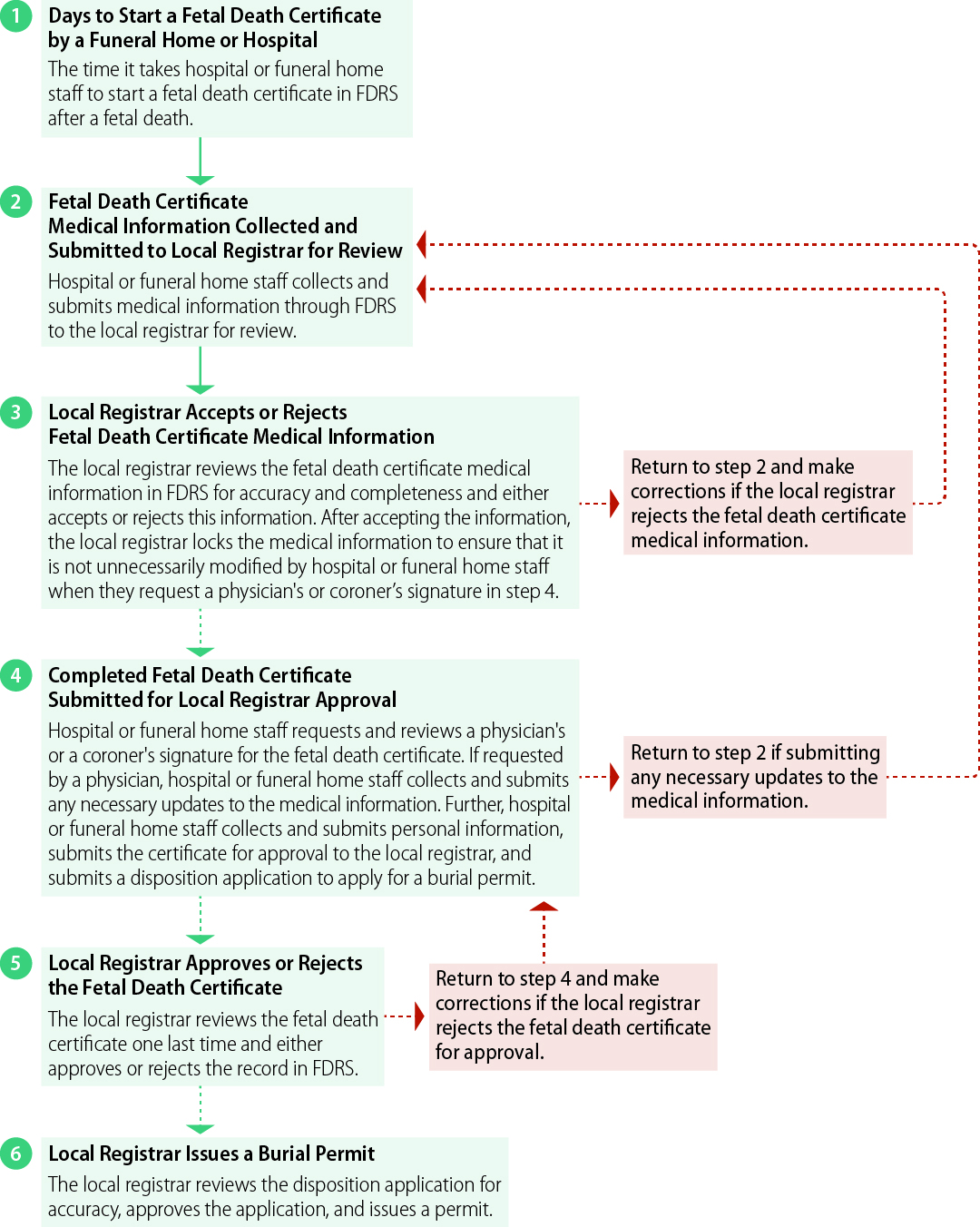

Because state law governing fetal death registration does not specify the precise sequence of events in the registration process or specify who is responsible for creating a new certificate, we analyzed FDRS data and interviewed local registrar staff to understand the fetal death registration process in practice. Using the information we learned from the data and registrar staff, we divided the registration process into six distinct steps that we observed occur in most cases. Figure 2 describes those six steps and the parties who may be involved in completing each one. Steps 1, 2, and 4 are typically completed by hospital staff, funeral homes, or, in some cases, the coroner’s office; steps 3, 5, and 6 are completed by the local registrar.

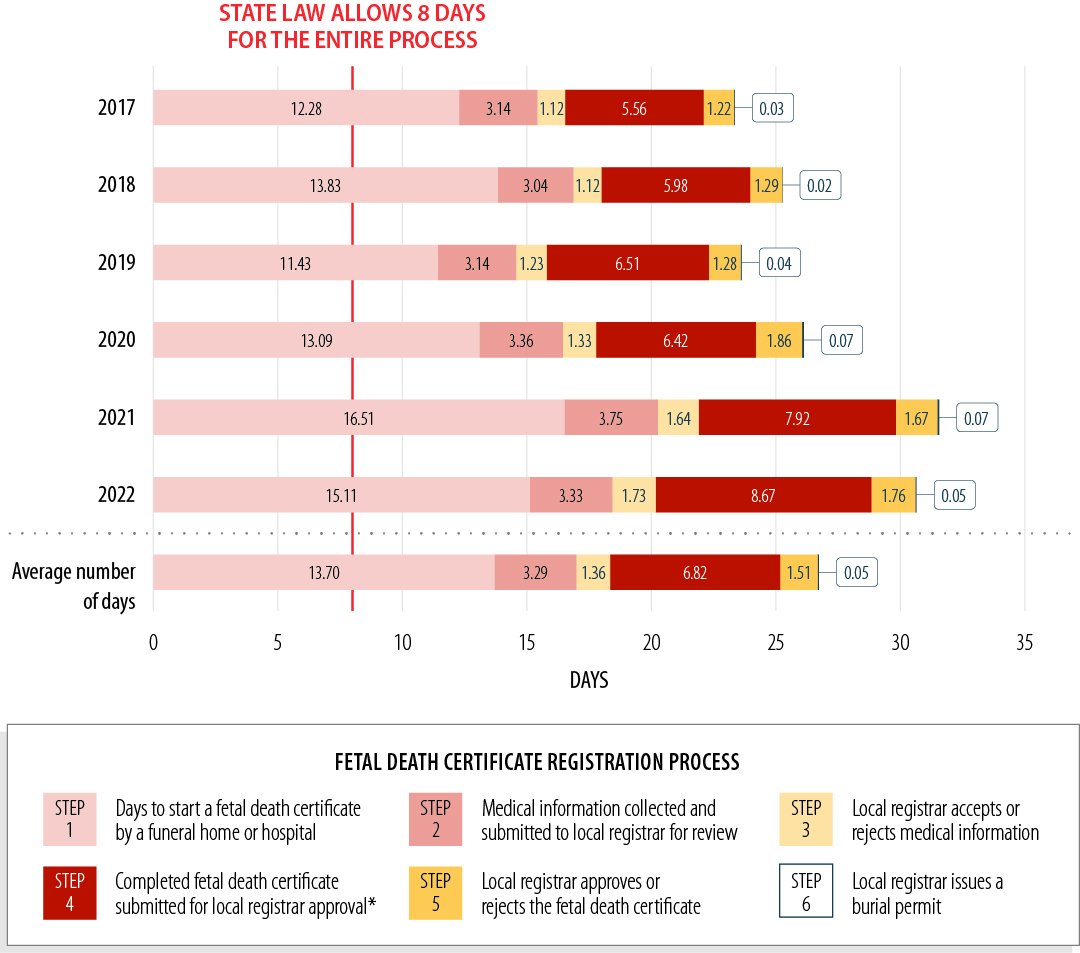

In general, registration delays did not occur while certificates were awaiting review or approval by local registrars. Figure 3 shows the results of our analysis of the number of days that elapsed during each of the six steps in each year we reviewed. For steps 3, 5, and 6, we found that local registrars reviewed and approved the medical information and fetal death certificates and issued a burial permit in about three days, on average. In contrast, the greatest delays in the process occurred during those steps that hospitals, funeral homes, or coroners generally complete: the first step, the initiation of a new fetal death certificate in FDRS; and the fourth step, the time it took to obtain the physician’s or coroner’s signature on the certificate, collect and input any updates to medical information, and submit the fetal death certificate to the local registrar for final approval.

Figure 2

Key Steps of the Fetal Death Registration Process at the Local Registration District Level

Source: CDPH’s Fetal Death Registration System and interviews with local registrars.

For example, Figure 3 shows that from 2017 through 2022, it took an average of almost 14 days for responsible parties to even start the registration process by creating a new death certificate in FDRS—nearly twice the time allowed in state law for the entire process.

Figure 2 Description:

A flowchart displaying the six steps generally taken during the process of registering a fetal death certificate at the local registration district level. Step 1 is the time it takes to start a fetal death certificate by hospital or funeral home staff after a fetal death. Step 2 involves the collection of medical information on the fetal death certificate by hospital or funeral home staff, and the submission of this information through FDRS for the local registrar to review. Step three involves the local registrar accepting or rejecting the fetal death certificate medical information collected in step 2. The local registrar reviews the certificate’s medical information for accuracy and completeness and either accepts or rejects this information. If the medical information is incorrect, the local registrar rejects the medical information and the process returns to step 2, allowing the hospital or funeral home staff to make corrections. If the medical information is correct, the local registrar accepts the information and locks the certificate to ensure that it is not unnecessary modified by hospital or funeral home staff when they request a physician’s or coroner’s signature in step 4. In step 4, the completed fetal death certificate is submitted for local registrar approval. Hospital or funeral home staff requests and reviews a physician’s or coroner’s signature on the fetal death certificate, updates medical information, submits personal information, submits the certificate for approval to the local registrar, and submits a disposition application to apply for a burial permit. In step 5, the local registrar reviews the fetal death certificate one last time and either approves or rejects the record in FDRS. If the local registrar rejects the certificate, the process returns to step 4 to allow hospital or funeral home staff to make corrections. If the local registrar approves the certificate in FDRS, the process moves to step 6, which involves the local registrar reviewing the disposition application for accuracy, approving the application, and then issuing a burial permit.

Figure 3

Throughout the State, Fetal Death Certificate Registration Has Consistently Taken Longer Than State Law Allows

Source: CDPH’s Fetal Death Registration System and interviews with local registrars.

Note: Some FDRS records lack data in one or more of the above steps, which can lead to a different overall average. As a result, the sum of steps one through six in the above bars do not exactly match those in Table 1.

*This step includes obtaining a physician’s or a coroner’s signature, updating medical and entering personal information, submitting the certificate for approval, and applying for a burial permit.

Figure 3 Description:

Figure 3 displays a bar chart showing that, from 2017 through 2022, the fetal death registration statewide consistently took longer than the eight days allowed in state law. Each bar corresponds to a calendar year, and is comprised of the six different steps in the fetal death registration process. On average, from 2017 through 2022, Step 1, the days to start a fetal death certificate by a funeral or hospital, took an average of 13.70 days. Step 2, where medical information is collected and submitted to the local registrar for review, took an average of 3.29 days. Step 3, the time it takes a local registrar to accept or reject the medical information in a certificate, took an average of 1.36 days. Step 4, the time it takes to obtain a physician’s or a coroner’s signature, updating medical and entering personal information, submitting the certificate to the local registrar for approval, and applying for a burial permit, took an average of 6.82 days. Step 5, the time it takes a local registrar to approve or reject the fetal death certificate, took an average of 1.51 days. Step 6, the time is takes a local registrar to issue a burial permit, takes an average of 0.05 days. In 2017, the statewide average for step 1 is 12.28 days, step 2 is 3.14 days, step 3 is 1.12 days, step 4 is 5.56 days, step 5, is 1.22 days, and step 6 is 0.03 days. In 2018, the statewide average for step 1 is 13.83 days, step 2 is 3.04 days, step 3 is 1.12 days, step 4 is 5.98 days, step 5, is 1.29 days, and step 6 is 0.02 days. In 2019, the statewide average for step 1 is 11.43 days, step 2 is 3.14 days, step 3 is 1.23 days, step 4 is 6.51 days, step 5, is 1.28 days, and step 6 is 0.04 days. In 2020, the statewide average for step 1 is 13.09 days, step 2 is 3.36 days, step 3 is 1.33 days, step 4 is 6.42 days, step 5, is 1.86 days, and step 6 is 0.07 days. In 2021, the statewide average for step 1 is 16.51 days, step 2 is 3.75 days, step 3 is 1.64 days, step 4 is 7.92 days, step 5, is 1.67 days, and step 6 is 0.07 days. In 2022, the statewide average for step 1 is 15.11 days, step 2 is 3.33 days, step 3 is 1.73 days, step 4 is 8.67 days, step 5, is 1.76 days, and step 6 is 0.05 days.

Four Local Registrars We Reviewed Generally Manage the Fetal Death Registration Process in the Same Way and Experience Delays During the Same Steps of the Process

We reviewed local registration processes and responsibilities at each of the four districts to identify any key differences. We found that all four local registrars have established equivalent roles and responsibilities related to the fetal death registration process and have each designated staff to serve as liaisons to hospital, funeral home, and coroner personnel. Further, all four local registrars explained that they follow the instructions outlined in CDPH’s FDRS handbook for fetal death registration and burial permit issuance. Staff at the four local registrars may also undergo CDPH’s training regarding the use of FDRS and the process for registering a fetal death and issuing a burial permit. However, state law does not specify the precise sequence of events in the registration process or specify who is responsible for creating a new certificate. In the absence of such direction, local registrars do not enforce external roles or responsibilities; rather, they work with whichever party happens to be completing those steps in a given case.

Processing times for fetal death registrations at the four local registrars varied considerably but, as is the case statewide, frequently exceeded the eight‑day time frame specified in state law. Contra Costa had the shortest average processing time for registering a fetal death (nearly 13 days), whereas Sacramento had the lengthiest (37 days). Contra Costa also had the lowest percentage of late fetal death registrations—66 percent of all its fetal death registrations exceed legal time frames—whereas Los Angeles had the highest rate, at 91 percent. Table 2 shows the total number of fetal deaths during our review period, the average registration processing time, and the percentage of timely and late registrations at each of the four local registration districts.

A broad review of CDPH’s vital statistics data provides information about how long it took to register a fetal death, but it cannot help us understand the circumstances—such as insufficient staffing or waiting for information from grieving families—that caused the delays. Therefore, to obtain perspective about how delays could be mitigated, we examined individual fetal death registration records from the four local registrars. This FDRS data obtained from CDPH includes a chronological sequence of activities for each registration, such as the dates and times parties used the system to start, modify, or submit certificates for review and approval. We also selected 80 fetal death registration cases—20 from each of the four local registrars. Because the local registrars do not maintain additional documentation of any interactions, such as case notes or emails with outside parties, we had to rely on the FDRS data from CDPH as well as interviews with staff at the four local registrars, at related hospitals, and at funeral homes when assessing the causes for individual delays.

KEY IMPROVEMENTS IN THE FETAL DEATH REGISTRATION PROCESS COULD MITIGATE PRIMARY CAUSES OF DEATH

The results of our review indicate that individual steps of the registration process proceed more quickly when hospitals play a lead role in the process. Hospitals may be better equipped than funeral homes, for instance, to determine that a fetal death has occurred and to collect and input necessary medical information. We also identified a gap in the functionality of FDRS: the system does not automatically notify parties when a certificate is awaiting their action. If that notification were added to CDPH’s new data system, CDPH could better ensure the timely coordination among the parties involved in the registration process.

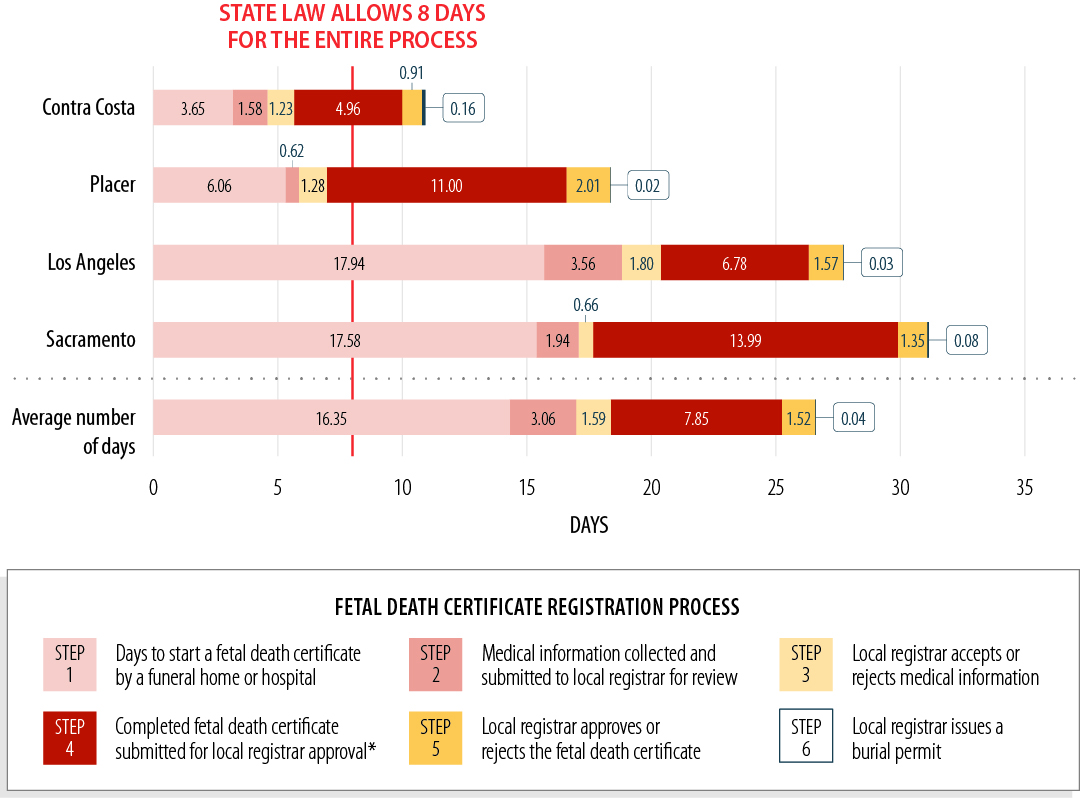

The Fetal Death Registration Process Moves More Quickly When Hospitals Begin the Registration Process

Consistent with our statewide analysis of CDPH’s data, our equivalent analysis of the data specific to the four local registration districts shows that the most significant delays occurred during two steps of the fetal death registration process. The longest delays, on average, occurred during the first step of the process, the initiation of a new fetal death certificate in FDRS. From 2017 to 2021 at the four local registration districts we reviewed, staff at hospitals, funeral homes, and coroner’s offices took an average of 16 days to start a new fetal death certificate in FDRS—twice the time allowed for the entire process in state law.5 As Figure 4 shows, the second‑longest delay occurred during the fourth step, when staff at hospitals or funeral homes obtain the physician’s or coroner’s signature on the certificate, collect and update any medical or personal information, and submit the completed fetal death certificate to the local registrar for final approval: this step took an average of nearly eight days. Our review of individual cases found evidence that, during this fourth step, funeral home staff or hospital staff may also be attempting to respond to physicians’ or registrars’ requests for more complete or accurate medical information that would otherwise have been collected during step two.

Figure 4

Among the Districts We Reviewed From 2017 Through 2021, Fetal Death Certificate Registration Has Consistently Taken Longer Than State Law Allows

Source: CDPH’s Fetal Death Registration System and interviews with local registrars.

Note: Some FDRS records lack data in one or more of the above steps, which can lead to a different overall average.

*This step includes obtaining a physician’s or a coroner’s signature, updating medical and entering personal information, submitting the certificate for approval, and applying for a burial permit.

Figure 4 Description:

Figure 4 displays a bar charts showing that, from 2017 through 2021, the fetal death registration in the four local registration districts under review consistently took longer than the eight days allowed in state law. Each bar corresponds to one of the four local registration districts we reviewed, and is comprised of the six different steps in the fetal death registration process. On average, from 2017 through 2021 and across all four registration districts, Step 1, the days to start a fetal death certificate by a funeral or hospital, took an average of 16.35 days. Step 2, where medical information is collected and submitted to the local registrar for review, took an average of 3.06 days. Step 3, the time it takes a local registrar to accept or reject the medical information in a certificate, took an average of 1.59 days. Step 4, the time it takes to obtain a physician’s or a coroner’s signature, updating medical and entering personal information, submitting the certificate to the local registrar for approval, and applying for a burial permit, took an average of 7.85 days. Step 5, the time it takes a local registrar to approve or reject the fetal death certificate, took an average of 1.52 days. Step 6, the time is takes a local registrar to issue a burial permit, took an average of 0.04 days. In the Contra Costa district, the average for step 1 is 3.65 days, step 2 is 1.58 days, step 3 is 1.23 days, step 4 is 4.96 days, step 5, is 0.91 days, and step 6 is 0.16 days. In the Placer district, the average for step 1 is 6.06 days, step 2 is 0.62 days, step 3 is 1.28 days, step 4 is 11 days, step 5, is 2.01 days, and step 6 is 0.02 days. In the Los Angeles district, the average for step 1 is 17.94 days, step 2 is 3.56 days, step 3 is 1.80 days, step 4 is 6.78 days, step 5, is 1.57 days, and step 6 is 0.03 days. In the Sacramento district, the average for step 1 is 17.58 days, step 2 is 1.94 days, step 3 is 0.66 days, step 4 is 13.99 days, step 5, is 1.35 days, and step 6 is 0.08 days.

FDRS data indicate that, on average, funeral home staff across the four local registration districts started the registration process by creating more than 61 percent of the new fetal death certificates, and hospitals created about 33 percent of certificates. As Table 3 shows, staff at funeral homes take more time to start a new fetal death certificate in FDRS, on average, than staff at hospitals do. This trend was most pronounced in Placer, where funeral homes averaged 12 days to start a new fetal death certificate in FDRS and hospitals averaged only three days. As Table 3 shows, funeral homes across the four local registrars took an average of 15 days to start a new certificate following a fetal death—nearly twice the time frame allowed for the entire process in state law.

Several factors may contribute to a funeral home’s staff taking a relatively long time to start a fetal death certificate in FDRS. First, funeral home staff can only begin the process after they are notified that a fetal death has occurred, and local registrars told us that funeral homes would generally not be made aware of the death until the family has selected the funeral home and has begun to make funeral arrangements. It could, understandably, take a family a considerable amount of time to select a funeral home. In addition, the Los Angeles local registrar told us that some fetal deaths occur at hospitals that do not have access to FDRS, and the Placer local registrar indicated that not all hospitals have staff with the specific responsibility to start a fetal death certificate in FDRS. When a hospital lacks access to FDRS, the funeral home then becomes responsible for starting the certificate in FDRS, which can only occur after the funeral home learns of a fetal death from the family. Finally, funeral homes may encounter challenges that could cause delays in starting a fetal death certificate in FDRS. An owner, who explained he owns five funeral homes, stated that delays occur at his facilities for a variety of additional factors, including lack of training on fetal death registration and staffing issues.

In contrast, hospital staff can start new fetal death certificates in FDRS significantly sooner. As we show in Table 3, staff in hospitals across the four local registration districts started new fetal death certificates in FDRS in an average of only eight days, or about half the time taken by staff in funeral homes. Local registrars explained that the shorter time frames for hospital staff to start new fetal death certificates likely occur because hospital staff have access to information in the hospital’s database that a fetal death has occurred.

Moreover, the data indicate that in addition to hospital staff generally starting new fetal death certificates more rapidly than do staff at funeral homes, hospital staff started new certificates in FDRS in even shorter time frames when they performed this task frequently—that is, when the task was part of their accustomed duties. For example, hospital staff in the Contra Costa registration district started 89 percent of new fetal death certificates and started them three times faster than did funeral home staff in the district. In contrast, hospital staff in Los Angeles started only 24 percent of new fetal death certificates and were only about 25 percent faster than funeral home staff in the district. Still, data across the four local registration districts show that regardless of the frequency with which hospitals start fetal death certificates, they conduct the process more rapidly than funeral homes.

As a practical consideration, hospital staff are also more likely to have direct access to the medical and personal information required during intermediate steps of the registration process. According to staff at hospitals from each of the four local registration districts, medical facilities that maintain patient records during patient care and treatment are more likely to have direct access to the types of medical information required during the registration process. Moreover, local registrars explained that while a patient is in the hospital, staff may be likely to have direct access to the patient to collect the personal information required in a fetal death certificate. Indeed, despite the fact that FDRS data indicates funeral homes often coordinate the collection of medical information for fetal death certificates, state law currently makes attending physicians responsible for entering any required medical information into the certificate. We identified nine individual cases across the Sacramento, Placer, and Contra Costa local registration districts in which the data specific to district records show that hospital staff completed at least the first three steps of the registration process—starting the fetal death certificate, entering required medical information, and having the local registrar accept the medical information—and obtained the physician’s signature before transferring the certificate to a funeral home. For these nine cases, those processes took a combined average of roughly three days to complete, compared to the 18 days it took to complete the first three steps of the registration process statewide.

The second‑longest delay in the registration process involves the time it took to obtain the physician’s or coroner’s signature on the certificate, collect and input any updates to medical information, and submit the fetal death certificate to the local registrar for final approval. Increased hospital involvement in the process of registering fetal death certificates may also reduce these sources of delays. Although state law does not specify which party is responsible for starting the fetal death certificate, it does mandate that within 15 hours of the delivery, the attending physician state the cause of death and any required medical information in the certificate, and then sign the certificate. For the four registration districts we reviewed, physicians took an average of four days to sign a fetal death certificate after staff at a hospital or funeral home sent a signature request. Yet as Table 4 shows, the process went much faster in districts where hospital staff made the majority of these requests. For example, hospital staff in the Placer registration district made these requests 70 percent of the time, and among the districts we reviewed, it had the lowest average time for physicians to respond—less than one day. In contrast, hospital staff in the Los Angeles registration district made only 26 percent of the physician signature requests, and, among the districts we reviewed, physicians took significantly longer to sign—an average of more than six days overall. In fact, our review of a selection of individual cases from each of the four registration districts identified some signature requests from funeral home staff to physicians that went unanswered for several days. In one case from the Sacramento registration district, a funeral home submitted three separate requests over nine days before a physician ultimately signed the certificate. According to the local registrar, these delays could occur for a variety of reasons, including that the physician is busy or is out of the office.

Our review indicates that delays in obtaining physicians’ signatures may be compounded by the need for funeral homes to update or correct required information before doing so. We identified several instances in which delays occurred because funeral home staff likely faced challenges obtaining medical information from a hospital, personal information from a family, or both, during which time the certificate remained inactive in FDRS. In one case from the Placer local registration district, data specific to the district indicates that funeral home staff entered at least some medical and personal information one day, then left the certificate inactive for nearly five days, after which the staff entered additional information before submitting the certificate for local registrar review. The local registrar explained that there are several possible reasons for this type of delay. For example, some funeral home corporations may own and operate up to five funeral homes with only one staff member having access to FDRS. If this staff member is unavailable for any reason, that absence could delay the registration process. The registrar also stated that funeral homes may have difficulty obtaining medical information because the records are not always in a centralized location or because the attending physician’s rotating work schedule makes the physician unavailable.

In another case, data for the Los Angeles registration district showed funeral home staff entering information into a fetal death certificate two days after the certificate had been started, but then the certificate was inactive for six days. We cannot conclude with certainty in any case we identified that during such periods of a certificate’s inactivity, the funeral home was actively working to obtain medical information from the hospital or personal information. However, the fact that hospital staff completed these processes faster on average supports the idea that the funeral homes’ need to coordinate and communicate with other entities contributed to otherwise potentially avoidable delays.

Collectively, the information we gathered supports the conclusion that fetal death registrations proceed more rapidly and efficiently overall when hospitals start the fetal death certificate and provide the required medical and personal information. Table 5 demonstrates this efficiency. For instance, Table 5 shows that Contra Costa hospitals started 89 percent, or 192, of the fetal death certificates for its local registration district in FDRS, and those completed registrations took an average of 12 days—the highest proportion of hospital‑started certificates and the shortest average times of the four districts. According to the local registrar, hospital staff likely start certificates faster because information about a fetal death is located in the hospital’s database. When hospitals begin the fetal death certification process, families are not placed in the position of starting the fetal death registration process themselves by choosing and contacting a funeral home. Moreover, hospitals have access to the necessary medical information needed to complete the fetal death certificate in FDRS. Hospitals do not carry the administrative burden that funeral home staff encounter when they are required to contact the hospital to obtain the medical information needed to proceed with the certification process. Delays may still understandably occur as families make decisions that can affect the registration process, but when hospitals take the lead role in starting the new certificates and entering key information into the certificates, it will help ensure that families face minimal delays in obtaining necessary certificates and permits.

Coroners’ Involvement May Contribute to Fetal Death Registration Delays, But Coroners Are Only Involved In Few Cases Statewide

Coroners sign only a small percentage of fetal death certificates statewide. Generally, state law requires a coroner to examine and determine the circumstances, manner, and cause of all violent, sudden, or unusual deaths. State law also requires funeral homes and physicians to immediately notify a coroner of a death that occurred as a result of such causes or circumstances. However, state law provides coroners with the discretion to determine the extent to which they will investigate certain deaths. In these cases, if the coroner determines that the physician of record has sufficient knowledge to reasonably state the cause of death, the coroner may authorize the physician to sign the death certificate. From 2017 through 2021, coroners signed 813 fetal death certificates statewide, or about 7 percent of all certificates.

Although we identified some delays when coroners signed the fetal death certificate, the reasons for the delays are not clear because the data in FDRS does not contain explanations for what occurs during sometimes long periods of apparent inactivity. For instance, in one case investigated by a coroner in the Los Angeles registration district, the data show that the coroner took more than 90 days to create the new fetal death certificate, sign it, and submit it to the local registrar. The data also show that the local registrar registered the fetal death and issued a burial permit within the same day, but no available information in FDRS explains why the coroner took 90 days to create the certificate. The Los Angeles coroner explained that staff made several attempts to notify the family for the interment of the fetus’s remains. Seventy‑five days after the fetal death, the coroner began processing the fetal death certificate outside of FDRS, and 92 days after the fetal death, the coroner started the new fetal death certificate in FDRS, signed it, and submitted it to the local registrar for registration. It is possible that some of the delays we observed may be less avoidable because a coroner’s examination of a fetal death from unusual or unclear causes could reasonably be expected to take additional time.

One Coroner’s Office staff member in the Placer district told us that the time to review a fetal death occurring under circumstances such as violent, sudden, or unusual deaths could range from one to two weeks. However, some delays we observed may be prevented or lessened if the system used to register fetal deaths were able to automatically notify parties when a certificate is awaiting their action. In another case containing a significant delay before the coroner completed the review, the FDRS data show that after a hospital referred the case to the Sacramento coroner for review, 41 days elapsed before the coroner completed the file review. Although we cannot conclude with certainty the specific causes of the delays or determine whether the coroner was responsible for the entire inactivity in these cases, it is possible that the coroner’s not being promptly alerted to the fetal death contributed to the delay. Two of the four coroners in the local districts we reviewed explained that delays in these type of cases could include circumstances in which a hospital or funeral home does not immediately notify the coroner of a fetal death under its jurisdiction or could reflect the fact that FDRS does not notify the coroner when a hospital or funeral home refers the case to them.

CDPH Could Improve Its Registration System’s Ability to Notify Parties That a Certificate Is Awaiting Their Action

FDRS users—including physicians and hospital staff, coroners, and funeral home staff—may frequently have been unaware that a fetal death certificate required their attention. FDRS was not designed to notify a user that a certificate has been transferred by another for their action—such as when a hospital transfers a certificate to a funeral home or when a funeral home requests a physician’s or coroner’s signature. CDPH’s Vital Records Registration Branch chief (branch chief) explained that FDRS’s notification capability was limited to generating a list of fetal death certificates and notifying responsible parties, when they log into the system, about the number of fetal death certificates that had at that point exceeded the eight‑day registration requirement. The branch chief explained that CDPH intended that these notifications regarding the number of past‑due certificates would motivate the parties to continue gathering the information required for registration. However, the effectiveness of this notification mechanism was limited by the fact that it only affected certificates that had already exceeded the eight‑day time frame and that notifications were only visible when a user logged into FDRS. As a result, parties who were not logged into the system were not notified about a pending action required to move a death certificate along in the process.

Our review found that this limitation in FDRS likely contributed to delays in overall registration timeliness among some of the cases we reviewed. Our review of 80 cases identified at least 35 instances of delays occurring because a party was likely unaware that a certificate awaited action. In one case from the Placer district, the local registrar and funeral home did not view the certificate for five days and three days, respectively, after it was transferred to them for review. Local registrar staff said they were not entirely sure why the certificate was inactive for this amount of time but speculated that they had learned about the certificate being delayed by receiving a phone call from the funeral home.

To limit these types of delays, each of the four registrars either direct registrar staff to proactively check FDRS to identify whether a certificate is pending their action or they request that FDRS users notify them by fax, phone, or email that a certificate is pending the registrar’s action. When a user submits a certificate for review to the local registrar, it appears in the local registrar’s list of pending certificates, but registrar staff do not receive an automatic notification of the new certificate. In response to this limitation, Contra Costa has implemented a written policy that FDRS users notify the registrar by fax when they have submitted a certificate for review. Los Angeles has a written policy directing its staff to periodically monitor the electronic registration system throughout the day for new fetal death certificate submissions. Placer staff explained that the registrar’s office has an unwritten practice in which they request funeral homes and medical facilities to notify them that a certificate has been submitted to the local registrar for review. Notably, each of the seven hospitals and eight funeral homes we spoke with stated that they use other means to communicate with parties outside of FDRS regarding a certificate’s status, for these same reasons. Although this type of proactive coordination among the parties involved could help reduce delays in general, CDPH could more efficiently facilitate that coordination by implementing a mechanism within its fetal death registration system that automatically notifies users when a certificate requires their action.

CDPH could remedy this issue by ensuring that its newer electronic system for registering fetal deaths, EBRS, is capable of automatically notifying users each time a certificate is pending their action. Further, it could be helpful to send these notifications outside of the EBRS system, such as by sending an email. CDPH noted some potential difficulties in sending these notifications but explained that it has nonetheless included a change request for a notification mechanism in the scope of work for its new Cal‑IVRS contract.

CDPH COULD USE ITS AUTHORITY AND AVAILABLE INFORMATION TO BETTER ENSURE THE TIMELY REGISTRATION OF FETAL DEATHS

CDPH has not regularly used its FDRS data to determine possible reasons for delays or address these delays with the parties it oversees. CDPH could better oversee the fetal death registration process by coordinating and tracking the performance of responsible parties and by providing needed information to the state entities empowered to take administrative action when private entities do not comply with registration time frames.

CDPH Has Not Used All Available Information to Help Ensure Timeliness

As part of its responsibility to oversee the registration of fetal deaths in the State, CDPH maintains an electronic registration system to store information related to that process. Before it began using EBRS to register fetal deaths in June 2023, CDPH used FDRS to track the number and timeliness of fetal death registrations. However, CDPH has not regularly used its access to fetal death registration data to detect late registrations and intervene with parties involved. CDPH indicated that it is broadly aware of delays in fetal death registration and that it previously had in place an undocumented process for monitoring registration data. The department explained that the top priority of its Vital Records staff is to certify fetal death certificates when a local registrar registers a fetal death and that in the past, when staff had time available outside of those duties, staff used to review FDRS for registration certificates aged more than 30 days and send emails to notify local registrars of their late status. Certificates aged more than 30 days, we note, are those that have taken nearly four times longer than state law allows. The extent of the department’s past efforts are unclear, however, since CDPH could only provide us with eight notification emails, all sent during one month in 2017. The department explained that it stopped performing this type of monitoring notification in 2020 because of staff limitations related to the pandemic.

CDPH stated that fetal deaths are a small percentage of overall deaths and that the emails it provided to us are representative of how few fetal death registrations were past due. However, the data clearly indicate otherwise: from calendar years 2017 through 2022, 84 percent of fetal death registrations surpassed the eight‑day period. The department said that it reestablished the process of sending email notifications to local registrars beginning in November 2023. However, our review indicates that local registrar staff are generally aware of delays, suggesting that CDPH’s oversight efforts might achieve greater benefits if they focused on the likely causes of or trends in delays revealed by analyses similar to those we performed.

Although CDPH is aware of fetal death registrations that exceed the eight‑day time frame, it has neither accessed nor evaluated FDRS data to determine specific information about the underlying causes of delays. According to CDPH, staff have reviewed these data in limited circumstances to address a specific complaint or inquiry. However, CDPH explained that it has not evaluated these data in any way comparable to our analysis to determine the steps in the process causing the greatest delays or reviewed individual registrations to determine the reasons delays occur. The FDRS data contains a multitude of information that could be analyzed to determine causes of delays, as we demonstrate throughout this report, and CDPH could use those data to monitor the current performance of parties involved in the fetal death registration process to try to prevent late registrations. Until CDPH uses this information regularly, the issue of fetal death registrations lagging behind legal time frames will likely persist.

CDPH Could Use Its Authority to More Consistently and Effectively Ensure Fetal Death Registration Timeliness

Although improvements to the fetal death registration process and database that we identified will likely help reduce delayed registration, CDPH should implement further changes and more actively oversee the process. For example, state law authorizes CDPH to hold meetings with local registrars to discuss problems related to vital records registrations, including fetal death registration, in order to promote uniformity of registration policies and procedures. CDPH stated it holds these meetings with local registrars quarterly. However, CDPH could also hold similar meetings with hospitals and funeral homes, and this regular communication and collaboration with all parties involved in the fetal death registration process could help CDPH to identify causes of and solutions to the delays. For instance, CDPH could use these meetings to discuss potential solutions to address the greatest contributors to delays, such as the step in which the parties start a new fetal death certificate in EBRS.

If CDPH were to hold regular meetings, those meetings could also help identify other areas of concern involving the fetal death registration process or the data systems used to register deaths, and they might lead to solutions beyond those our review already identified. In fact, the branch chief explained that CDPH once held monthly meetings with local registrars and funeral homes to gain perspective on their concerns with the fetal death registration process but discontinued them in 2017. The branch chief is uncertain about the reason behind this decision but explained that CDPH is open to restarting these meetings. She said that CDPH intends to begin holding meetings again by June 2024 to discuss vital records registration—including the fetal death registration process—and plans to include in these meetings local registrars, hospitals, funeral homes, physicians, and coroners. However, she also noted that the large number of hospitals, funeral homes, physicians, and coroners in the state could create logistical difficulties, and she stated that CDPH may be better positioned to invite representatives from professional organizations representing these entities. Regardless of CDPH’s exact approach when holding these meetings, it must ensure that the meetings offer an avenue for parties involved in the fetal death registration process to learn of their responsibilities and provide their perspective to CDPH on potential process improvements.

CDPH could also offer better assistance to those involved in the registration process. The department operates a help desk that provides assistance to FDRS users who require it, but our review was unable to determine the extent to which that effort has helped with the timeliness of registration. Local registrar staff in both Contra Costa and Placer expressed concerns about the adequacy of the help desk’s response to their inquiries. The Contra Costa local registrar stated that the help desk telephone is frequently not answered and that the registrar has not received responses to emails since the pandemic. Placer staff told us they no longer call the help desk because staff there have rarely answered the telephone since the onset of the pandemic. Although CDPH stated that its help desk is responsive to and effectively provides support for all fetal death registration inquiries, the department could not provide any evidence of inquiries it had received, nor could it demonstrate its responsiveness to such inquiries, such as telephone records or email documentation. We were therefore unable to assess the quality and usefulness of the assistance CDPH has provided through this tool.

Finally, CDPH could do more to ensure that hospitals and funeral homes are aware of their obligations in the fetal death registration process and have access to the data system used to fulfill those obligations. CDPH explained that it does not conduct outreach or provide guidance to hospitals and funeral homes and that it relies on these parties to contact CDPH to request registration training and access to FDRS. The department said that it presumes that if hospitals or funeral homes are required to register fetal deaths as part of their business operation, they should be aware of the fetal death requirements outlined in state law. CDPH also said that it would grant access to any hospital or funeral home that requested FDRS access but that it cannot require hospitals or funeral homes to adopt FDRS. However, the department also stated that some hospitals have contacted it for guidance because they have been uncertain about the requirements in state law.

Indeed, data provided by CDPH shows instances in which a hospital or funeral home attends to fetal deaths and lacks access to FDRS. Of the 10 hospitals in Los Angeles that reported the largest numbers of fetal deaths from 2017 through 2021, two lacked access to FDRS yet reported 20 percent of fetal deaths across those 10 hospitals (216 of 1,091). Similarly, three of eight hospitals where fetal deaths occur in the Sacramento district, and which handled 20 percent of fetal deaths (101 out of 504), also lack access to FDRS. In Contra Costa, one funeral home, which handled 5 percent of fetal deaths (seven of 133) among the top 10 funeral homes likely providing burial services in the county, lacks access to FDRS.

CDPH explained that when hospitals or funeral homes lack access to FDRS, they must rely on other parties that do have access to start the fetal death certificate process and populate the necessary information. Because fetal death registration proceeds more rapidly and efficiently overall when hospitals start certificates in FDRS and provide the required medical and personal information, we believe that all hospitals should have access to and training on CDPH’s newer electronic system for registering fetal deaths, EBRS, and on the requirements in state law. The Legislature could therefore reduce delays in fetal death registrations by requiring hospitals to start this process. Similarly, CDPH could take a more proactive approach and contact hospitals and funeral homes that lack EBRS access to provide them with instructions on obtaining access. These hospitals and funeral homes could then be equipped to fulfill their responsibilities in the fetal death registration process and help to mitigate late registrations.

Overseeing the Timeliness of Fetal Death Certificate Registrations Will Require CDPH to Coordinate With Other State Oversight Entities

Although CDPH is the state entity responsible for overseeing fetal death registration, state law does not grant CDPH the specific authority to impose administrative sanctions, such as administrative fines, against physicians and funeral homes in response to registrations that exceed established time frames. Rather, state law establishes criminal penalties for the failure to fill out a fetal death certificate or register it with the local registrar in the manner required by law, and authorizes CDPH to refer these violations to the district attorney. State law also provides CDPH with supervisory power over local registrars so that there will be uniform compliance with all vital records requirements and authorizes CDPH to adopt regulations for the enforcement of vital records requirements. CDPH’s branch chief said that as a result of its lack of authority over funeral homes, coroners, and physicians, CDPH can only notify a local registrar that a fetal death registration has exceeded the eight‑day requirement. When we asked the branch chief about the need for regulations related to fetal death registration, she explained that CDPH began developing regulations before the pandemic. However, since May 2022, CDPH has been undergoing an organizational restructuring, and the position responsible for overseeing the development of regulations was not filled as of December 2023. She also explained that any proposed regulations would include consideration of all vital records state laws, in addition to state law concerning fetal death registration, and that developing and implementing such regulations could take CDPH several years.

State law already grants the ability to impose administrative sanctions on physicians and funeral homes for fetal death registration timeline violations to two other state entities within the California Department of Consumer Affairs—the Medical Board of California (Medical Board) and the Cemetery and Funeral Bureau (Funeral Bureau).6 However, investigatory and enforcement efforts by the Medical Board and the Funeral Bureau are complaint‑driven, meaning that these entities currently only become aware of a violation when a member of the public files a complaint. Both the Medical Board and the Funeral Bureau investigate these complaints to determine whether a violation occurred and, if warranted, take corrective action. We reviewed complaints related to fetal death registrations that the Medical Board provided for the years 2018 through 2023, and complaints resulting in citations that the Funeral Bureau provided for the years 2017 through 2022. However, during these time periods, the Medical Board conducted only five investigations related to fetal death registration, and the Funeral Bureau conducted only one which resulted in a citation because of a funeral home’s violation of state law. These six investigations represent a negligible proportion of the total fetal death registrations recorded in FDRS that exceeded time frame requirements. Given the volume of those registration delays, the infrequency of these investigations indicates the need for an improved process.

Because CDPH neither notifies these entities when physicians or funeral homes are in violation of fetal death registration timelines nor provides them with access to the system that CDPH currently uses to track fetal death registration, the Medical Board and the Funeral Bureau are unaware of the actual scale of late registrations throughout the State. Without this information, the Medical Board and the Funeral Bureau have limited ability to ensure that physicians and funeral homes register fetal deaths in compliance with the law. As part of our review, we assessed whether actions taken by the Medical Board and the Funeral Bureau that resulted from their investigations aligned with each entity’s policies and state law. Although we did not identify any clear shortcomings in these investigations, we are concerned that they do not represent a sufficient level of overall enforcement. Moreover, because those investigations represent a negligible proportion of the total time‑frame violations we found, we are concerned they are of limited use for investigating and deterring violations.

CDPH explained that although its previous fetal death registration system lacked the ability to generate a report demonstrating the timeliness of fetal death registrations, its current fetal death registration system possesses this capability. If CDPH were to use this functionality to provide fetal death registration timeliness data to the appropriate disciplinary entity, such as the Medical Board or the Funeral Bureau, that entity would then be better aware of timeliness violations in fetal death registrations. Therefore, expanding its use of its current data system and serving as the coordinating body with the Medical Board and the Funeral Bureau would help CDPH better ensure compliance and potentially address the causes of delayed registrations.

Both the Funeral Bureau and the Medical Board agreed that if CDPH were to regularly notify them of registration delays, these notifications would be helpful to their oversight efforts. The Funeral Bureau said that receiving notifications about untimely registrations would allow it, depending on available resources, to begin investigating the reasons for the violation without requiring a family to file a complaint. The Funeral Bureau explained that in addition to the key dates surrounding the fetal death and registration, it would need other information that might be confidential, including information about the funeral home and the identifying information of the deceased. Similarly, the Medical Board explained that receiving notifications regarding late registrations could be beneficial to enhancing its awareness of time‑frame violations but also stated that it would need CDPH to provide information required by federal and state privacy laws to obtain consent to access relevant medical records to investigate a potential violation. Since each entity would require different, potentially confidential information to investigate a potential violation, it may be necessary for the Legislature to amend state law to require that CDPH coordinate with relevant licensing entities—such as the Medical Board and Funeral Bureau—to provide the data and information on fetal death registration timeliness violations necessary for these entities to learn of and investigate these violations.

Recommendations

Legislature

To improve the average time it takes for fetal death registration statewide, the Legislature should amend state law to require hospitals, or any medical facilities where fetal deaths may occur, to initiate the creation of the fetal death certificate for any fetal deaths that occur at their facilities. In doing so, the Legislature should reaffirm that physicians, or hospital staff as their delegates, are responsible for entering the required medical information into the fetal death certificates and should clarify that physicians must sign the certificates before transferring responsibility for the next steps of certificate completion to funeral homes.

To ensure the effective enforcement of fetal death registration timeliness requirements, the Legislature should amend state law to require CDPH to regularly notify the Medical Board, the Funeral Bureau, and any other relevant licensing entity, such as the Osteopathic Medical Board, of instances in which registration data indicate that physicians or funeral establishments are repeatedly failing to comply with these requirements. The notification should include the information necessary for the licensing entity to adequately investigate delinquent fetal death registrations.

California Department of Public Health (CDPH)

To reduce the time that parties involved in the fetal death registration process take to notify one another that a certificate is pending action, CDPH should, by June 2024, submit a request to its registration system vendor to develop and implement in the system an electronic notification mechanism that will alert the appropriate user outside the system, such as by email, that a certificate is awaiting that user’s action.

To better fulfill its duty to oversee the fetal death registration process, CDPH should, by June 2024, begin to hold meetings regularly with local registrars to identify and resolve issues related to fetal death registration. CDPH should include in such meetings representatives for parties involved in the registration process—such as hospitals, physicians, and funeral homes—as well as representatives from relevant licensing entities—such as the Medical Board and the Funeral Bureau—to obtain additional perspectives about ongoing causes for delays.

To better ensure the effectiveness of its help desk, CDPH should, beginning in June 2024, periodically survey local registrars to solicit feedback on their experience with the help desk and should use this feedback to improve help desk processes as necessary.

To mitigate registration delays and ensure that all hospitals and funeral homes with a responsibility to complete their portions of fetal death certificates are able to rapidly fulfill their obligations, CDPH should, by June 2024, notify hospitals and funeral homes that lack access to its registration system for fetal deaths of their legal obligations in the fetal death registration process and provide instructions on how to access the data system used to fulfill those obligations.

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards and under the authority vested in the California State Auditor by Government Code section 8543 et seq. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on the audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

February 29, 2024

Staff:

Laura G. Kearney, Deputy State Auditor

Mark Reinardy, Audit Principal

Grayson Hough, Senior Auditor

Shawn Butler

Stephen Franz

Katrina Solorio

Legal Counsel:

Natalie Moore

Appendices

Appendix A

LOCAL REGISTRATION DISTRICTS’ AVERAGE PROCESSING TIMES FOR COMPLETING FETAL DEATH REGISTRATIONS