2023-106 University of California

It Makes Limited Use of Online Program Management Firms but Should Provide Increased Oversight

Published: June 6, 2024Report Number: 2023-106

June 6, 2024

2023-106

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the University of California (UC) and its use of online program management firms (OPMs). The following report details the audit’s findings and conclusions. Overall, we determined that UC makes limited use of OPM firms to provide online education but should provide increased oversight to better ensure transparency for students.

We identified 51 UC contracts with OPMs in effect as of January 1, 2023, none of which involved undergraduate education. Of those contracts, 30 were with the five UC campuses we selected for review—Berkeley, Davis, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Santa Barbara—of which 15 pertained to continuing education provided through campuses’ extension units. We found that each of these campuses provided potential students with incomplete or misleading information about the OPMs’ involvement in some programs—such as not disclosing whether the OPM was teaching the class—or overstating the value of those programs. Additionally, we found that some of the campus extension units did not consistently adhere to their processes for approving courses or instructors.

The campuses lack systemwide guidance from the UC Office of the President (Office of the President) on contracting with OPMs. For example, although the Office of the President recommends that campuses not engage in incentive compensation—such as tuition revenue sharing—when contracting with third parties to recruit undergraduate students, this guidance does not address graduate or continuing education students. Further, some of the contracts included payment terms that may elevate the risk of OPMs using practices to recruit and enroll students that are not in the best interests of students. To mitigate the risks of using OPMs, the Office of the President should establish systemwide guidance that ensures transparency about OPMs’ involvement in educational programs, enables campuses to provide adequate oversight of OPMs, and protects prospective students from potentially abusive recruiting practices.

Respectfully submitted,

Grant Parks

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| BEE | UC Berkeley Executive Education |

| ED | U.S. Department of Education |

| GAO | U.S. Government Accountability Office |

| OPM | online program manager |

| UC | University of California |

| WASC | Western Association of Schools and Colleges |

Summary

Online courses and programs have become increasingly common in higher education. Many colleges work with third-party vendors known as online program managers (OPMs), which assist in the development and implementation of online programs. OPMs generally provide instruction and support services, such as marketing, recruiting, course development, and technology-related support. In this audit, we examined the University of California’s (UC) use of OPMs at five campuses—University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley); University of California, Davis (UC Davis); University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA); University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego); and University of California, Santa Barbara (UC Santa Barbara)—and drew the following conclusions:

UC Uses OPMs to Teach Students in Some Nondegree Programs but Is Not Always Transparent About Doing So

We identified 51 UC contracts with OPMs that were in effect as of January 1, 2023, none of which involved undergraduate education. Of those contracts, 30 were with the five campuses we selected for further review, and 10 of those 30 related to graduate education. However, these 10 contracts involved support services rather than instruction. Of the 30 contracts we reviewed, 15 related to continuing education, which UC provides through extension units that are associated with campuses but that operate independently. Under the terms of these 15 contracts, OPMs were responsible for providing instruction. However, at the five UC campuses we selected to review, we found that the campuses provided potential students with incomplete or misleading information about the OPMs’ involvement in certain extension unit programs. Further, the recruitment materials for one or more programs at each campus may have misled potential students about the industry value of some UC cobranded programs offered in conjunction with OPMs.

UC Extension Units Have Not Provided Consistent Oversight of OPM Instruction

Because most campuses did not consistently adhere to their course‑approval processes or administer or examine student course evaluations for the OPM-instructed courses we reviewed, they may lack adequate assurance that students are receiving satisfactory education from qualified instructors. Each of the extension units at the five campuses we reviewed have adopted processes for approving OPM-provided courses, instructors, or both. These processes generally align with UC Academic Senate regulations. However, in contrast to the other four extension units, UC Santa Barbara Professional and Continuing Education (Santa Barbara Extension) does not have a process to approve OPM instructors, increasing the risk that those instructors may not be adequately qualified. Further, the extension units for UC Berkeley, UCLA, and UC San Diego did not consistently follow each step of their course and instructor approval processes and thus may also lack assurance that OPM instructors are adequately qualified. Compounding these weaknesses in oversight, the extension units for UCLA and UC Santa Barbara have not consistently performed or reviewed student course evaluations to monitor the quality of OPM instruction. These campuses may be overlooking information that could help to ensure that their OPM courses and instructors are effective.

Campuses Lack Certain Guidance From the Office of the President on Contracting With OPMs

The five campuses’ contracts with OPMs largely aligned with federal law and guidance on incentive compensation. However, some of the contracts included payment terms, such as tuition revenue sharing, that may elevate the risk of OPMs using practices to recruit and enroll students that are not in the best interests of students. In addition, we identified several instances in which campuses outsourced key services to an OPM, despite best practices stating that those services should not be outsourced.

Introduction

Background

Enrollment in online education has increased significantly over the past decade. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the proportion of college students nationwide enrolled in online education courses increased from about 26 percent of total enrollment in 2012 to nearly 59 percent in 2021. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of online education increased in 2020 to more than 73 percent. Although it has since decreased from pandemic levels, online education continues to play a significant role in higher education.

The UC’s governance comprises several entities. The text box describes the system’s governance structure. UC provides education through three divisions: undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education offered through extension units. The UC undergraduate and graduate education divisions provide degree programs to enrolled UC students, while extension units provide a variety of courses to a broader student population. Before enrolling in courses, undergraduate and graduate programs require students to go through an admissions process that includes minimum admission requirements established by the Academic Senate. In contrast, extension units use open enrollment, which permits students to register for UC courses without going through an application and admission process. Extension units provide some courses that offer credit that students may apply toward a degree. The UC Office of the President (Office of the President) indicates that extension units do not receive any ongoing support from the State’s General Fund, and the Board of Regents of the University of California (Board of Regents) exempts nondegree extension unit courses from the Academic Senate’s oversight of courses and curricula.

UC System Governance

UC Board of Regents

- Establishes and oversees university policies, financial affairs, tuition, and fees.

- Appoints the president of the university.

UC Office of the President

- Administers the central functions of UC, such as managing the UC budget and administering benefits and retirement plans.

- Manages certain academic aspects of UC, including maintaining the admissions process and administering student financial assistance.

- Establishes systemwide policies and guidance.

Academic Senate

- Empowered by the Board of Regents to decide academic policies, including approving courses and establishing requirements for admission, certificates, and degrees.

- Provides a structure for faculty to participate in the shared governance of the UC and ensures the quality of instruction, research, and public service at UC.

- Advises the administration on faculty appointments, promotions, and budgets.

Source: UC website and Academic Senate bylaws and regulations.

UC Online Education

UC teaches undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education students in person at its 10 campuses, and it also provides students with online instruction. Undergraduate degree programs may include online courses, although their use is currently limited compared to graduate and extension unit programs. However, in December 2023, the UC President approved the establishment of a presidential task force to assess methods of delivering instruction and to consider criteria for online bachelor’s degree programs of a quality expected from UC. Later, in February 2024, the Board of Regents declined to approve an Academic Senate regulation that would have established a minimum requirement of instructional hours in person and on campus for an undergraduate student to be eligible for a bachelor’s degree. The proposed regulation would have essentially prohibited the offering of a fully online undergraduate degree. In contrast, as of January 2024, UC does offer several fully online graduate programs that culminate in graduate degrees.

Further, UC provides continuing education online through extension units at nine of its 10 campuses. UC San Francisco is the only campus that does not have an extension unit. These extension units are administratively self-contained and operate independently from campuses under systemwide policies. This independence permits the extension units’ open enrollment model, through which all potential students have access to continuing education that is intended to enhance their skills.

Online Program Managers

Like many other universities and colleges, UC contracts with OPMs to support its online programs with services such as marketing, recruiting, course development, technology-related support, and instruction. In general, colleges may contract with more than one OPM for different services or to support different online education programs. The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that as of July 2021, at least 550 colleges nationwide were working with an OPM to support at least 2,900 online education programs. OPMs provide support to a range of education programs, including undergraduate degree programs, graduate degree programs, intensive skill‑based programs such as boot camps, continuing and professional education programs, and public online courses—also known as massive open online courses. Such offerings are open enrollment online courses, meaning that any member of the public may enroll in them, and they are developed by the universities or OPMs and hosted on the OPMs’ websites. According to the GAO, OPMs receive payment for their services through a share of tuition revenue, a predetermined fee, or both.

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee (Audit Committee) directed our office to determine the extent of partnerships between OPMs and a selection of five UC campuses, the level of transparency provided to prospective students, the quality of instruction provided, the level of student satisfaction with the associated courses or programs, student outcomes, and compliance with federal and state laws. For this audit, we examined OPM use at UC Berkeley, UC Davis, UCLA, UC San Diego, and UC Santa Barbara, which we selected based on enrollment, the extent of campuses’ online programming, and public information about the campuses’ use of OPMs.

Issues

UC Uses OPMs to Teach Students in Some Nondegree Programs but Is Not Always Transparent About Doing So

UC Extension Units Have Not Provided Consistent Oversight of OPM Instruction

Campuses Lack Certain Guidance From the Office of the President on Contracting With OPMs

UC Uses OPMs to Teach Students in Some Nondegree Programs but Is Not Always Transparent About Doing So

Key Points

- UC does not use OPMs to teach students in undergraduate programs, and it generally uses OPMs for support services only in graduate programs. UC uses OPMs to teach students in extension unit programs.

- The information that campuses provided about some extension unit programs that used OPM instructors may have misled prospective students about the OPMs’ roles. Campuses did not consistently provide background information about the OPM instructors.

- Campuses’ recruitment materials may have misled potential students about the industry value of some OPM programs.

UC Does Not Use OPMs to Teach Students in Programs That Confer Degrees

For this audit, we requested and reviewed all OPM contracts that were in effect as of January 1, 2023.1 We identified 51 OPM contracts within the UC system, 30 of which involved the five campuses we selected for review. Eight of these 30 contracts had expired as of May 2024 or were terminated by the campuses. We identified contracts by conducting interviews with knowledgeable campus personnel, such as the deans of extension, graduate, and undergraduate education, and by confirming the universe of contracts with the chancellor or executive vice chancellor of each campus.2

None of the contracts we identified involved undergraduate education. As Figure 1 shows, 10 of the 30 contracts we reviewed involved graduate education or a graduate program, but these contracts did not include OPM instruction. Instead, nine of these contracts for graduate programs included OPM marketing or student support services, such as student career counseling and technical support. Programs also contracted with OPMs to provide technical assistance in course development, including by collaborating with UC faculty to produce course content, such as videos, for an online format.

Figure 1

Five Campuses We Reviewed Contracted With OPMs to Provide Services for Three Main Categories of Education

Source: Review of OPM contracts at selected campuses.

* Three of 10 graduate OPM contracts support graduate schools in providing UC curriculum for non-credit online programs. One contract that was intended for online degree program support was used instead to market extension courses.

The five campuses we reviewed had a total of 30 contracts with online program managers (OPMs).

An OPM is a third-party contractor that offers services that enable to offer online educational content.

Services OPMs may provide include instruction, course development, recruitment, marketing, technical support, publishing course content on open-access websites, and student support services.

The 30 OPM contracts we identified provided for programs that fell into one of three categories: Extension Programs, Graduate Programs, and Public Online Courses.

Extension/Continuing Education Courses (Nondegree)

For these 15 contracts, OPMs partner with UC extension units. The associated programs are primarily developed and instructed by OPMs. Other services that the OPMs provide include marketing, recruiting, and student support services. These programs are typically non-credit and do not confer degrees, although they may offer certificates of completion.

Graduate Programs* (No OPM Instruction)

Graduate divisions contract with OPMs mostly to support online graduate degree programs. For the 10 contracts we identified, the curriculum is developed and taught by UC faculty. Students are admitted through a standard UC graduate application process. OPM services may include recruiting, marketing, collecting applications, technical support, and student support services.

Public Online Courses (Nondegree)

These courses are offered online to the public and are commonly known as Massive Open Online Courses. For the five contracts that we identified, UC faculty develop the course curriculum, and OPMs host the courses on their own websites. They are frequently self-paced and free to access, typically generating revenue through add-ons, such as verified certificates of completion. These courses do not confer degrees, and we did not find that any provide UC credit.

* Three of 10 graduate OPM contracts support graduate schools in providing UC curriculum for non-credit online programs. One contract that was intended for online degree program support was used instead to market extension courses.

Various leaders of UC graduate programs described certain benefits associated with using OPMs, including the ability to rapidly increase course capacity, OPM expertise in setting up online education, and increased marketing capacity. All of the graduate degree programs we reviewed that use OPMs are self-supporting: the revenue generated by the program, such as student tuition, generally pays for the program’s costs. UC graduate school leadership told us that using OPMs made the development of some of these self-supporting programs financially feasible. For example, UC Berkeley’s agreement with an OPM to develop and administer an online Master of Information and Data Science program specified that the OPM would advance $25,000 each month to UC Berkeley during the program’s first year. The dean of UC Berkeley’s Graduate Division said that the OPM’s upfront investment made launching this new program feasible. Similarly, the dean of UC Davis’s Graduate School of Management stated that because of the significant upfront investment required, the school would not have been able to provide its online MBA program without an OPM’s involvement. The assistant dean of UCLA’s School of Engineering echoed this principle, saying that hiring its own marketing team for its online Master of Science in Engineering program would have been more costly than using an OPM for those services.

The remaining contracts primarily relate to UC’s use of OPMs to teach students in extension unit programs. Although these programs do not confer degrees, they typically offer awards of completion, and some programs result in academic credits and professional certificates, such as certificates in paralegal studies. The Board of Regents bylaws exclude nondegree extension unit courses from the Academic Senate’s responsibility to authorize and supervise courses and curricula. However, Academic Senate regulations do require approval by the dean of the extension unit and the relevant department or school for any extension unit curricula that lead to professional credentials or certificates. All 15 contracts we identified that included OPM instruction at the selected campuses pertained to extension unit programs.3 These OPM programs included courses for technology and coding boot camps, leadership and continuing education programs, paralegal studies programs, and other professional programs. Five of these programs were credit-bearing, and four of the five programs were approved in accordance with Academic Senate rules. We discuss the one course that was not appropriately approved in a later section of this report.

The deans of several extension units reported that they contracted with OPMs to provide online programming because the OPMs had the capacity and expertise the extension units lacked. For instance, UC Berkeley Extension’s (Berkeley Extension) dean stated that OPMs had capacity that Berkeley Extension lacked internally and that partnerships with them helped it to offer courses that it would not have been able to provide otherwise. UC Davis Continuing and Professional Education’s (Davis Extension) dean said that partnering with OPMs allowed the extension unit to fill curricular gaps and that the OPMs provided insight and experience that helped Davis Extension to develop its own capacities, such as modernizing its marketing practices.

The Office of the President and the Academic Senate generally impose less oversight on extension unit programs. The Office of the President’s executive advisor for academic planning and policy development stated that extension units have a high degree of independence from the Office of the President and systemwide Academic Senate oversight. He also stated that extension units are auxiliary and self-supporting, and they do not typically receive ongoing state funding. Academic policy and oversight at the Office of the President and the systemwide Academic Senate typically focuses on graduate and undergraduate degree-granting programs at the campuses. In fact, a representative of the Office of the President told members of the Academic and Student Affairs Committee in a May 2018 meeting that because extension units are self-supporting and dependent upon user demand, they need to be nimble and able to quickly launch new programs that are responsive to the needs of students and their employers. The representative added that the extension units allow UC to introduce and refine alternative models of program delivery, such as online education.

In Some Instances, Extension Units Provided Prospective Students With Incomplete or Misleading Information About OPM Courses

Properly disclosing who provides instruction for extension unit programs, along with other key information, helps prospective students make better decisions about which courses to take, and federal law requires such disclosure. The Higher Education Act of 1965 allows eligible educational institutions (institutions), such as qualifying institutions of higher education, to participate in authorized student assistance programs. Federal law prohibits these institutions from substantially misrepresenting certain factors about their educational programs, including the nature of a program, the program’s financial charges, and the employability of a program’s graduates. In July 2023, the U.S. Department of Education (ED) amended federal regulations to state that the omission of certain material information also constitutes misrepresentation. This information includes facts related to the factors described above and other elements, such as the identity of the entity that is actually providing instruction or implementing the institution’s recruitment, admissions, or enrollment processes. Misrepresenting such information about OPMs at UC could mislead students about the relationship between OPMs and the university and the roles OPMs play in the education students receive.

To review marketing and program information available to prospective students, we selected three to five contracts from each of the five campuses we reviewed and chose one program or course associated with each (selected programs). The 20 selected programs included both degree and nondegree programs and included courses that were taught by UC employees and courses taught by OPM employees. For each program, we reviewed the associated website and contacted program representatives, presenting ourselves as prospective students. We assessed whether key information included on the website or provided by program representatives was erroneous or could be construed as misleading. We also determined whether websites omitted those key pieces of information.

The campuses’ contracts with OPMs for the selected programs generally did not require that marketing materials disclose an OPM’s involvement. However, the majority of the selected program websites (16 of 20) disclosed that campuses partnered with OPMs to provide the programs, as Table 1 shows. The four programs for which campuses did not disclose the OPM’s involvement could mislead prospective students to believe that UC, rather than the OPM, provided the instruction. For example, Davis Extension’s paralegal studies certificate program did not disclose that it partners with an OPM or that the OPM provides instruction for this program. Davis Extension’s staff stated that because the program is credit bearing, it is subject to more academic governance and that Davis Extension views this program as more clearly belonging to the university. Nevertheless, an OPM provides instruction for this certificate program, a fact that federal law requires institutions to disclose, and Davis Extension did not make this clear to potential students. UC Davis’s senior director of strategic partnerships stated that his office would be open to disclosing the OPM partnership and outlining the parties’ respective roles. As of January 2024, Davis Extension had updated its website for the paralegal program, which now describes the partnership with the OPM and discloses that the OPM provides the curriculum and instruction, which is vetted by the UC Davis School of Law.

Most of the selected programs that involved OPM instruction provided minimal information on their websites about their instructors’ backgrounds. Such information could be of interest to a prospective student deciding whether to enroll in an educational program. Of the 20 programs we reviewed, 10 involved OPM instruction, yet only two of those 10 clearly disclosed on their program websites that an OPM was providing the instructors. Seven of those 10 also did not provide certain details on their websites about the instructors’ qualifications, such as the instructors’ education and experience. In contrast, the graduate programs we reviewed, whose instructors are employed by the universities, disclosed the instructors’ names and details about their academic or professional backgrounds. After we brought this issue to their attention, the five campuses we reviewed indicated that they would be open to assessing how they could identify the OPM course instructors and adding to their websites more information about their qualifications and the roles of the OPMs.

When we contacted program representatives, we presented ourselves as potential students and asked about the roles OPMs played in various programs. The program representatives generally answered our questions with accurate information. However, when we called UC San Diego’s Division of Extended Studies (San Diego Extension) about its additive manufacturing certificate program, a staff member told us that no third party was involved, which was inaccurate because OPM instructors taught two of its courses. San Diego Extension’s assistant dean of academic affairs said that it was difficult to determine why the staff member misstated this fact. She added that the unit’s program managers do not know everything about all programs and that it may have been that the staff member we contacted was not directly overseeing the additive manufacturing certificate program and was unaware of the third party. However, the assistant dean could not provide any specifics or evidence regarding the cause of the miscommunication. Further, the unit’s public website for this program does not disclose the OPM’s involvement in instruction, and the website lacked information about the program’s instructors. Consequently, if prospective students were to review the program’s website and speak with the extension unit staff member with whom we communicated, they would likely have an inaccurate understanding of who would teach certain courses. Thus, students could make decisions about whether to register and pay for courses based on incomplete information.

Although the additive manufacturing certificate program is still in place as of May 2024, San Diego Extension canceled the contract with the OPM for this program in April 2024, and the unit’s assistant dean stated that the two related OPM courses have not been offered since early 2023. She also stated that San Diego Extension had disclosed the campus’s partnership with the OPM in the course descriptions on the campus’s learning management system, where it said that the courses were created by the OPM. However, the learning management system is accessible only to students, so an individual who has not yet enrolled would not be able to acquire that information.

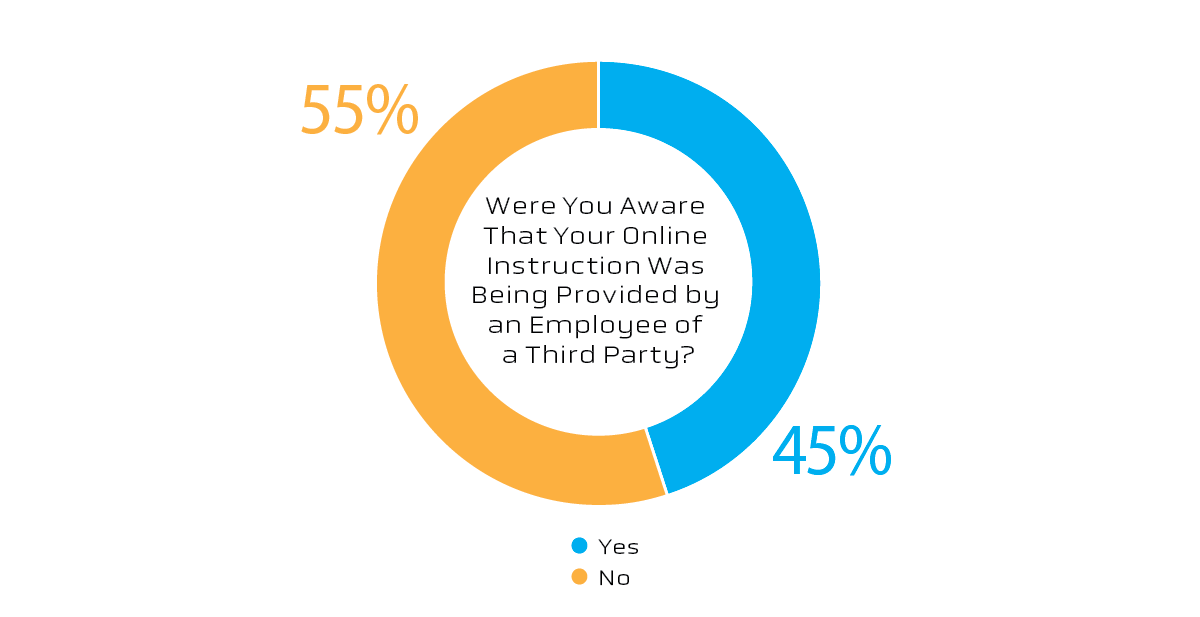

Because the learning management system is only available to students, inaccurate or incomplete information presented on the extension unit websites and by program representatives could lead prospective students to believe that instructors were part of UC faculty and not employed by the OPM. Moreover, our survey of students suggests that some students are concerned about who is teaching their courses. We conducted a survey of 3,320 students who took OPM-instructed courses in 2022 from the five extension units we reviewed. Slightly more than 10 percent of students, or 338 students, provided responses, which Appendix D presents in full. We cannot draw broad conclusions from the results because of the low response rate, which raises the possibility that a larger portion of the responses we received were from students who were displeased with their experiences. Nevertheless, as the text box shows, respondents expressed concerns about certain aspects of the OPM-instructed courses that they took. When we discussed the survey with each of the campuses, Berkeley Extension described its perspective that instructors identified and hired by the OPMs undergo the same vetting and approval processes as other Berkeley Extension instructors. However, not all campuses had the same vetting or approval processes for instructors hired by OPMs, as we discuss later. Even if the student survey responses do not represent the experiences of all students who enrolled in these courses, the fact that these students stated that they were not aware of the nature of the instruction they received is concerning.

Responses of Some Students Who Took OPM-Instructed Courses

Were you aware that the instruction for the course or program was being provided by an employee of a third‑party entity and not by university faculty?

No: 183 of 333 students answering the question

Would knowing that online instruction was being provided by a third party and NOT by university faculty have affected your decision to enroll or remain enrolled in the course/program?*

Yes: 122 of 183 students answering the question

Do you believe that program information misrepresented the course’s instructors as university instructors?

Yes: 101 of 332 students answering the question

Source: Respondents to a survey of participants in OPM‑instructed UC extension unit courses.

* Only students who answered “No” to the previous question had the opportunity to answer this question.

Of the five campuses we did not review, four had an additional 21 OPM contracts that were active as of January 1, 2023. We did not determine how many of those contracts are similar to those from the five campuses we examined. The problems we identified at the five campuses we reviewed suggest that the lack of disclosure that an OPM, rather than a UC campus, was providing instruction could limit prospective students’ ability to make informed choices about paying for and participating in these UC extension programs. Because we observed this situation at multiple campuses, systemwide guidance is warranted.

Marketing and Recruiting Materials Could Mislead Students About the Academic or Industry Value of Some UC OPM Programs

Prospective students seeking to enroll in educational programs predominantly geared toward working professionals and postgraduates rely, in part, on marketing and recruiting materials that promote the academic and industry value of the programs. However, the UC OPM programs we reviewed did not always provide accurate, complete, or current information about program outcomes, rankings, costs, or graduate employability, which may limit the ability of students to make knowledgeable choices regarding their education.

Misstating Student Outcomes and Market Demand

The OPM programs we reviewed at UC extension units generally related to professional advancement, and many of the program materials portrayed the programs as providing students with the skills and the support services needed to advance or change their careers. However, the websites included few facts related to student outcomes to support those portrayals. Specifically, the websites for 18 of 20 selected programs we reviewed did not include any student outcome information, such as the percentages of enrolled students who completed the program or obtained a certificate, graduates who obtained a job in a related field, or graduates who reported that their annual incomes increased. Staff for some campus programs described their intentions to collect and report student outcome information for their programs or indicated that they might already have some data on program completion and job placement rates. Others indicated that they would be cautious to draw a connection between their programs and certain outcomes or stated that it would be difficult to obtain this information from students.

The two OPM programs we selected that did provide student outcome information on their websites were intensive programs focused on developing technology skills that are in high demand—known as technology boot camp programs—that Davis Extension and San Diego Extension offered in partnership with an OPM. Although these programs’ websites disclosed job placement statistics, the statistics were not specific to graduates of the Davis Extension or San Diego Extension boot camps. Instead, the outcomes they described drew from the experiences of graduates from boot camps that the OPM offered in partnership with other entities. According to the OPM’s website, it offers boot camps with more than 30 institutions. Because the campuses’ portrayals of the programs’ ability to deliver job-related results are not supported by results specific to those campuses’ programs, it is not clear whether those portrayals are accurate.

Further, the UC websites for their OPM programs provided some misleading or incomplete information about the market demand for the skills the programs offered. The websites for 10 of the 20 selected programs either relied on outdated or unverified information or contained limited or misleading information about the job market, potential salaries, or graduate employability. For example, Berkeley Extension’s website for its digital marketing boot camp asserts that digital marketing jobs are “projected to grow 20 percent in the next decade… four times the average growth rate expected for all occupations, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.” However, the Berkeley Extension website does not cite a source for the digital marketing job growth projection, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics does not specifically report on the job outlook for digital marketing. Berkeley Extension’s assistant dean stated that the Bureau of Labor Statistics does not always map specific jobs to data in an easy-to-understand manner. However, she also noted that the contract with the OPM would allow the unit to request that website language be updated annually to present data that is more current.

Similarly, San Diego Extension’s website for its coding boot camp cited Indeed.com as stating that a variety of companies are currently seeking web developers in the San Diego area. However, the Indeed.com webpage to which the extension unit website linked did not show that the named companies were seeking developers in San Diego; rather, reviews and reported salaries indicated that one of the companies mentioned by San Diego Extension is a top company for web developers. Although the information and sources these campuses provided about their OPM programs may simply be out of date, it is not clear whether the information accurately characterizes the current conditions of the related industries. Without current information on the hiring conditions in relevant industries, students seeking professional education, such as through a coding boot camp, will be less able to make informed decisions about how to spend their education dollars.

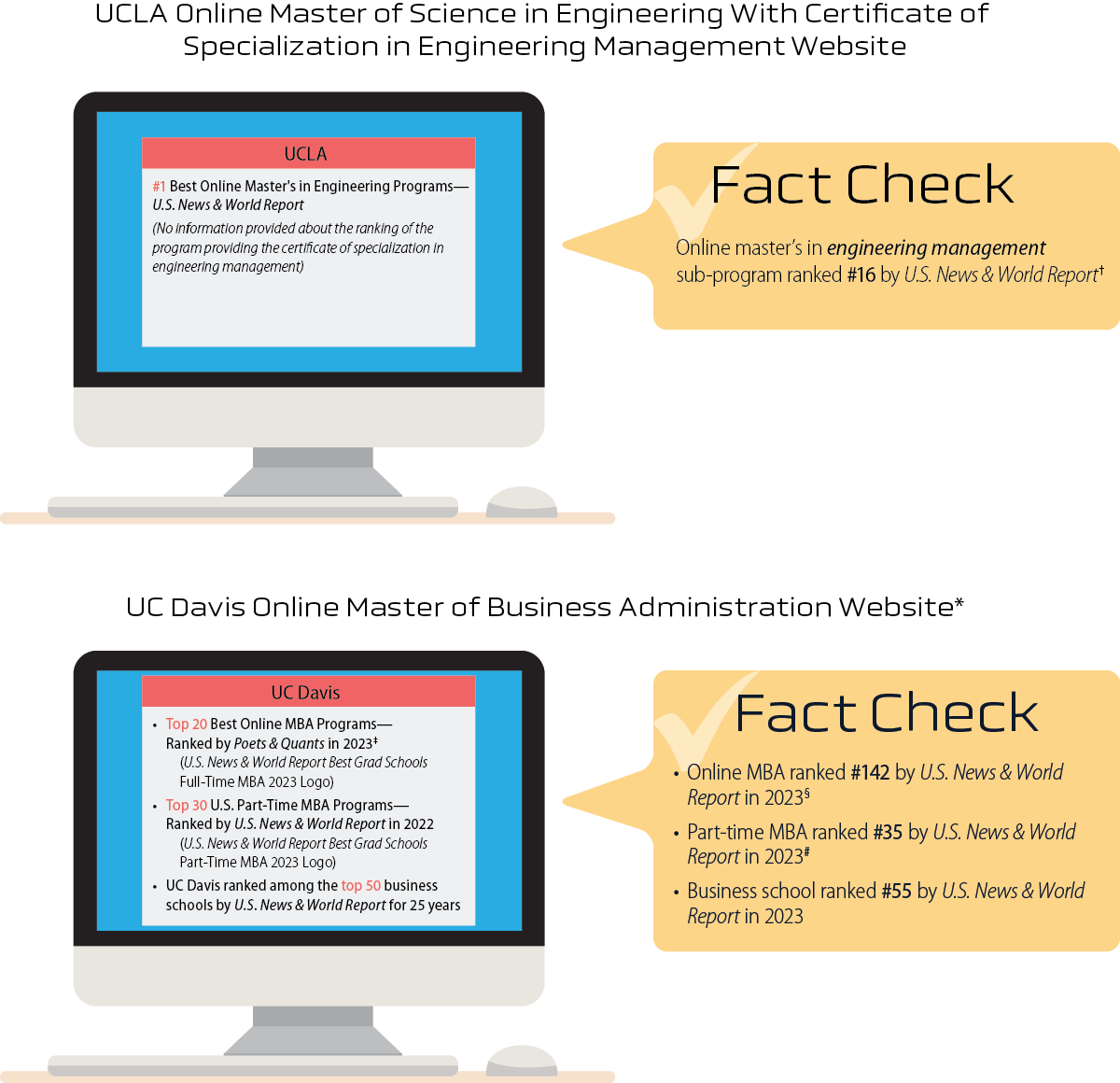

Overstating Graduate Program Rankings

Two graduate programs we reviewed at UCLA and UC Davis used misleading information or excluded details about the programs’ rankings, as Figure 2 shows. The assistant dean of UCLA’s School of Engineering indicated that UCLA did not publish the online Master of Science in Engineering program’s sub-program ranking as #16 for the certificate of specialization in engineering management (engineering management specialization) because U.S. News & World Report requested a significant amount of documentation to support the school’s ranking for the online graduate engineering program that it did not similarly request for the engineering management specialization within the overall program. The assistant dean also stated that these specialization rankings are based on subjective peer feedback and are not data driven. Still, although the engineering management specialization’s ranking may not be grounded in the same rigorous methodology as the overall program’s ranking, the information that UCLA presented about the specialization may have been insufficient for potential students considering the sub-program.

Figure 2

Two Graduate Programs Provided Misleading or Insufficient Information on Their Websites About Their Rankings

Source: UC program websites, U.S. News & World Report, and Poets & Quants.

* We identified concerns with the rankings on the two campuses’ websites in June and July 2023. UC Davis subsequently updated its website to remove references that were misleading.

† UCLA’s online master’s in engineering program was ranked #1 by U.S. News & World Report in 2023, whereas its online master’s in engineering management sub-program was ranked #16.

‡ UC Davis appeared to attribute another organization’s ranking to U.S. News & World Report.

§ UC Davis did not present the U.S. News & World Report ranking of its online MBA program on its website.

# UC Davis’s part-time MBA program was ranked in the top 30 of such programs during 2022, but next to that statement, the website presented a U.S. News & World Report logo from 2023, a year in which the part-time program was not ranked in the top 30 of such programs.

The first example is UCLA’s Online Master of Science in Engineering With Certificate of Specialization in Engineering Management website. The graphic shows a representation of a computer screen with the following information: #1 Best Online Master’s in Engineering Programs— U.S. News & World Report. No information was provided on the website about the ranking of the program providing the certificate of specialization in engineering management.

In fact, the online master’s in engineering management sub-program was ranked #16 by U.S. News & World Report.†

The second example is UC Davis’s Online Master of Business Administration Website.* The shows a representation of a computer screen with the following information:

Top 20 Best Online MBA Programs—Ranked by Poets & Quants in 2023.‡ Underneath this information, the website showed the U.S. News & World Report Best Grad Schools Full-Time MBA 2023 Logo.

In fact, the online MBA was ranked #142 by U.S. News & World Report in 2023. §

Top 30 U.S. Part-Time MBA Programs—Ranked by U.S. News & World Report in 2022. Underneath this information, the website showed the U.S. News & World Report Best Grad Schools Part-Time MBA 2023 Logo.

In fact, the part-time MBA was ranked #35 by U.S. News & World Report in 2023. #

UC Davis ranked among the top 50 business schools by U.S. News & World Report for 25 years.

In fact, the business school was ranked #55 by U.S. News & World Report in 2023.

* We identified concerns with the rankings on the two campuses’ websites in June and July 2023. UC Davis subsequently updated its website to remove references that were misleading.

† UCLA’s online master’s in engineering program was ranked #1 by U.S. News & World Report in 2023, whereas its online master’s in engineering management sub-program was ranked #16.

‡ UC Davis appeared to attribute another organization’s ranking to U.S. News & World Report.

§ UC Davis did not present the U.S. News & World Report ranking of its online MBA program on its website.

# UC Davis’s part-time MBA program was ranked in the top 30 of such programs during 2022, but next to that statement, the website presented a U.S. News & World Report logo from 2023, a year in which the part-time program was not ranked in the top 30 of such programs.

The UC Davis Graduate School of Management had already identified issues with the presentation of rankings for its online MBA at the time of our review. The school’s dean stated that the OPM involved with the program mistakenly believed that some of the U.S. News & World Report rankings were relevant to the online MBA. The dean said that the school has worked closely with the OPM’s marketing and internal compliance team to ensure that it follows UC Davis’s review and approval process. The rankings are now accurately attributed, and UC Davis no longer advertises a U.S. News & World Report ranking. However, it is not clear why UC Davis’s review process did not identify the inaccuracies before they were made public on its website. Program rankings are one way prospective graduate students may select a particular UC program, and inaccurate portrayals of such rankings are a disservice to students making this important decision.

Not Fully Disclosing Program Refund Policies

Information on UC extension units’ OPM program websites about program costs appeared to be accurate, but most program websites included minimal information about refund policies. The websites for four of the campus extension units describe a $30 to $40 drop or refund processing fee that generally applies to all extension unit courses. However, when we asked program representatives of four of the campuses’ technology boot camps about the refund policies, they informed us of a separate nonrefundable $1,000 deposit. The program websites made only passing reference to such a deposit and did not clearly disclose its nonrefundable nature or clarify the amount. As of May 2024, we had not observed changes to the websites. The program representatives stated that students must pay this $1,000 nonrefundable deposit even if they drop the program within a week of the first class. Awareness of this nonrefundable deposit might affect prospective students’ interest in these programs, especially those students of limited means. Nearly 20 percent of respondents to our survey who disclosed their annual individual income earned less than $29,000 in the year before enrolling in their program, and 67 respondents indicated that they obtained private loans to pay for the costs of their programs. Without disclosure of the amount of a nonrefundable deposit, prospective students cannot fully consider the financial commitment of enrolling in a program.

Use of Potentially Misleading Terminology

Some UC campuses and their extension units use terminology that could mislead students about the academic value of educational programs. Specifically, some OPM programs describe certificates or awards of completion using terms that sound similar to academic terminology but do not have the same meaning because they do not confer academic credit. For example, UC San Diego contracts with an OPM that uses the term MicroMasters for an open enrollment data science program that does not result in a master’s degree nor provide credit toward a master’s degree at UC San Diego. Because the term master’s generally denotes a graduate degree, terminology of this nature could be confusing to students. In fact, in a 2019 report on microcredentials, a task force of the UC Berkeley division of the Academic Senate raised concerns about misleading terminology, including this term. UC San Diego’s associate vice chancellor of educational innovation stated that its division of the Academic Senate has also expressed concerns about the term. However, as of May 2024, the program website still used this terminology.

Compounding the problem of using this misleading phrase, a UC San Diego representative for the MicroMasters program misrepresented its value when we inquired about it in the guise of a prospective student. He stated that although the program was not required for applications to UC San Diego’s online master’s program in data science, it was beneficial to the admissions process. However, according to both UC San Diego’s director of digital learning and its associate vice chancellor, an applicant’s completion of the MicroMasters program is not taken into account during the admissions process for UC San Diego’s master’s program in data science. The director of digital learning stated that the campus would review the website and speak with program representatives to ensure that information provided does not suggest a connection between the MicroMasters and master’s programs. She later stated that the program representative may have given incorrect information because the campus had not adequately communicated details about the differences between the two programs to all involved parties. Such omissions in communication could lead prospective students to believe that there were additional benefits, such as positively influencing the decision for admission to a degree program, that do not actually exist.

Lack of Defined Review Processes

Campuses typically have the authority to control how their programs are publicly presented: 26 of the 30 OPM contracts we reviewed made marketing materials subject to review by campus personnel. However, only one of the campuses we reviewed—UC Davis—could provide us with a written policy or procedure describing a structured process for reviewing marketing materials or website content. Davis Extension’s documented procedures apply primarily to the marketing strategy for launching a new program, although its senior director of strategic partnerships noted that the unit reviews web pages as necessary throughout the year and as part of its annual planning process. In contrast, UC San Diego’s director of digital learning stated that UC San Diego does not have a formal mechanism for overseeing the marketing or website content created by its OPMs, although the associate vice chancellor for innovation said the campus should adopt a formal process for reviewing marketing and website content. A senior international and business development manager for UC Santa Barbara Professional and Continuing Education (Santa Barbara Extension) stated that although the extension unit and the OPMs agree on initial strategy for marketing, the OPM may later make changes to web content directly without the unit’s approval. Despite two of its three contracts with OPMs requiring that marketing content be subject to Santa Barbara Extension’s approval, the unit does not routinely review website content and is thus unlikely to approve every item of content.

In response to our requests, campuses were able to provide some type of evidence that their staff had reviewed and approved certain content for most of the programs we assessed. However, some campuses were more thorough than others. For example, the UC Davis Graduate School of Management has created a tool for reviewing the messaging for its online MBA program that included tracking changes for the related website’s content. In contrast, although Berkeley Extension developed the marketing and web content for its paralegal studies certificate program, the unit could not provide any evidence that it had reviewed that content. The website stated that 82 percent of graduates surveyed would recommend this certificate. However, when we inquired about the statistic, Berkeley Extension determined that the statistic resulted from a graduate survey conducted in 2017, and the unit could not produce the survey when we requested it.

If Berkeley Extension had a periodic review process for its program websites, it might have identified the potentially outdated statistic and the need to reassess the opinions of paralegal studies graduates. By contrast, when we discussed with UC Davis the inaccurate citation of its graduate program’s rankings, its leadership was already aware of the issue and was in the process of addressing it with its OPM partner. These contrasting examples demonstrate that a thorough review process that identifies and tracks all of the website elements that need periodic review can be an effective method for ensuring that potential students have accurate information when determining whether to pursue particular courses.

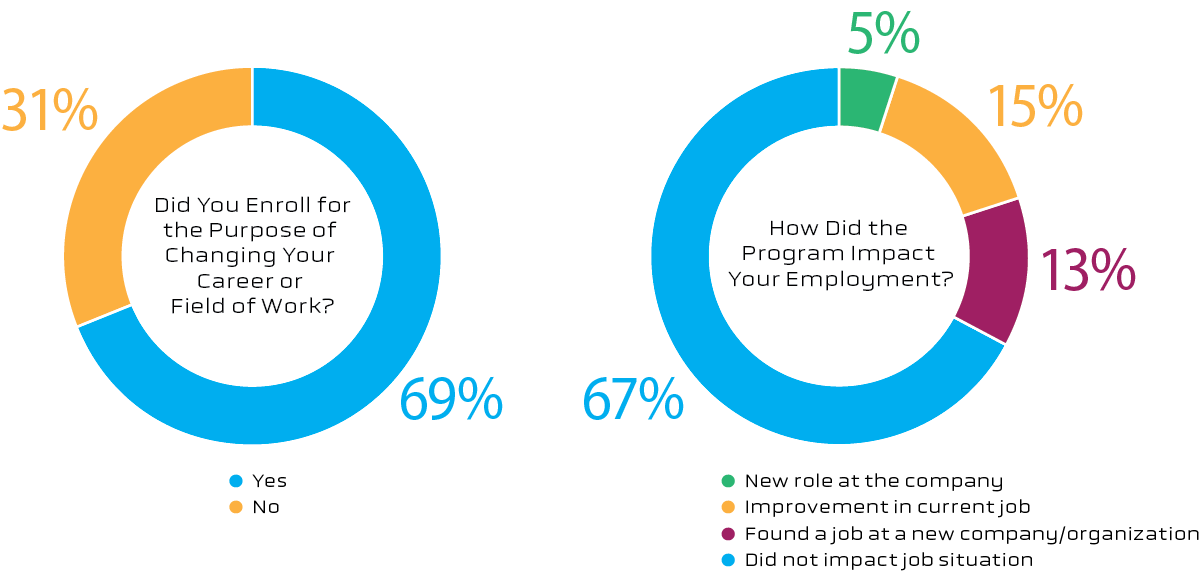

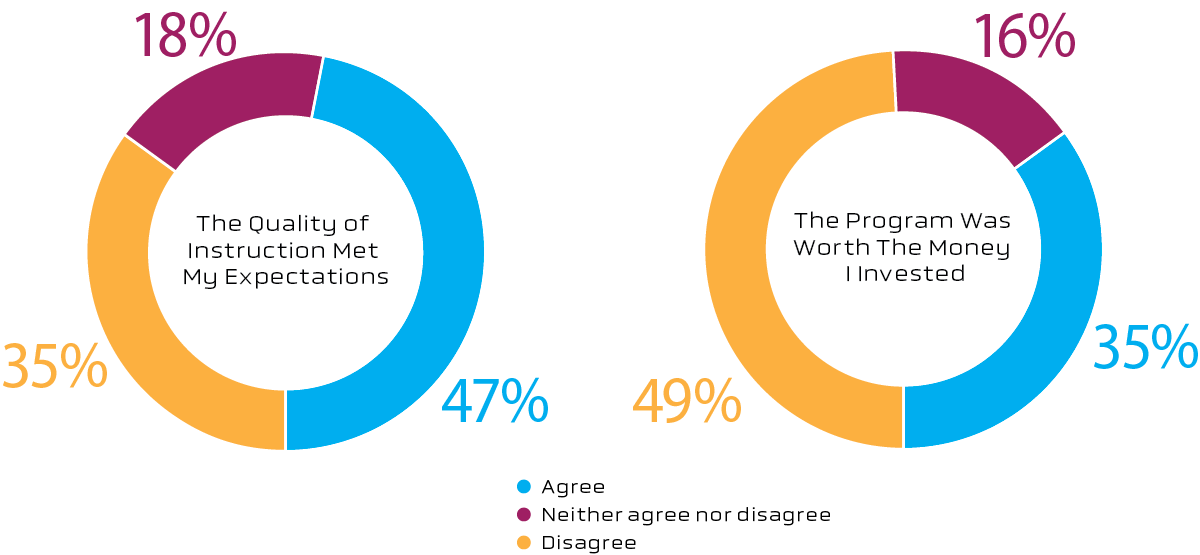

More than 60 percent of respondents to our survey indicated that campuses had misrepresented information about an OPM program in some manner. In particular, 136 respondents indicated that they felt their programs misrepresented the employability of graduates, and this factor seemed particularly important because nearly 70 percent of respondents answered that they enrolled in a program for the purpose of changing their career or field of work. However, about 67 percent of survey respondents indicated that the program or instruction they received did not impact their job or employment situation, and only 36 percent of survey respondents agreed that the program was worth the money they invested.

Many students who responded to our survey indicated that they chose to enroll at the extension unit at their specific UC campus instead of at another educational institution or provider because of the reputation or quality of the UC campus and the value that a certificate from a UC campus represents on their resumes. Encountering misleading or false information about OPM programs would likely tarnish students’ perception of the UC. More significantly, UC’s misleading or false information about OPM programs could lead students to invest their time and money in programs that will not provide the benefits advertised on UC or OPM websites. The shortcomings in the marketing information for OPM programs to potential students, along with responses to our survey, suggest that the campuses need additional guidance about how the programs should be marketed. As of May 2024, the Office of the President had not begun the process of sharing systemwide guidance about how transparent campuses should be regarding OPMs’ involvement in these programs. The Office of the President’s executive advisor for academic planning and policy development stated that the office is already drafting possible guidance and intends to start the process of vetting that guidance with stakeholders immediately following the publication of this audit report.

UC Extension Units Have Not Provided Consistent Oversight of OPM Instruction

Key Points

- Four of the five extension units have processes for approving OPM courses and instructors that generally align with Academic Senate regulations, including reviewing the qualifications of OPM instructors. In contrast, Santa Barbara Extension’s staff does not review its OPM instructors’ qualifications, increasing the risk that its instructors may not be suitable teachers.

- Berkeley Extension, UCLA Extension, and San Diego Extension did not consistently follow or could not demonstrate that they followed each step of their course approval processes, including reviewing OPM instructor qualifications. As a result, they may not be able to confirm that OPM instructors are adequately qualified to teach extension unit courses.

- UCLA Extension and Santa Barbara Extension do not consistently use or review student course evaluations to monitor OPM instruction. These campuses may overlook feedback that could help them better ensure the effectiveness of their OPM courses and instructors.

Santa Barbara Extension’s Process for Approving OPM Courses Does Not Assess Instructor Qualifications

Academic Senate regulations require that the relevant university department and the dean of the applicable extension unit approve courses that provide credit toward an academic degree or toward a professional credential or certificate. However, Academic Senate regulations do not require such an approval process for courses that do not meet these criteria, such as most technology boot camps.

Each campus had a process to approve OPM courses, instructors, or both. Staff at each of the extension units noted that their process for reviewing courses included examining the proposed course curriculum and other documentation before approving the course. Four of the five campuses we reviewed evaluated an instructor’s qualifications by reviewing a resume or other biographical information and some additional steps, such as obtaining references, conducting interviews, and observing the proposed instructor conduct a mock lesson. Because they review and approve instructors, the extension units at UC Berkeley, UC Davis, UCLA, and UC San Diego provide more assurance that their OPM instructors are qualified to teach the courses that OPMs offer through UC. Only Santa Barbara Extension did not have a process to approve OPM instructors.

According to Santa Barbara Extension’s senior international and business development manager, the unit does not see a need to oversee OPM instructors because the unit trusts its OPMs to ensure quality instruction. However, other extension units have identified concerns when reviewing the qualifications of prospective instructors. For example, Davis Extension’s senior director of strategic partnerships described an instance in which a potential instructor did not demonstrate the preferred level of confidence in teaching, nor did the instructor’s resume show substantial teaching experience. Davis Extension moved forward with approving the instructor after determining that the instructor exhibited strengths in teaching small groups and that the OPM would provide her with training and support. Without such a review process, students taking courses through the Santa Barbara Extension may not receive the quality of instruction they expect from the UC and for which they paid.

Santa Barbara Extension’s executive director said that the COVID-19 pandemic drove it to expand online course offerings and that student demand drove the unit to provide courses on coding through partnerships with other entities, such as OPMs. However, Santa Barbara Extension indicated that imposing additional processes, such as reviewing instructors’ qualifications, could potentially impact the economic benefits of using OPMs. Nevertheless, we found that such a process does not appear to be excessively time consuming or costly. For example, Davis Extension’s senior director of strategic partnerships said that the unit’s process for reviewing an instructor candidate’s application and qualifications usually takes 90 minutes to two hours if a candidate meets the unit’s requirements.

Some Extension Units Have Not Consistently Followed Their Own Processes for Overseeing OPM Courses and Instructors

Each of the five extension units we reviewed had processes in place to approve OPM courses, and four of them had processes in place to approve OPM instructors. However, the units must follow all of their processes to ensure effectiveness. We reviewed 21 courses in total, selecting at least four courses that each extension unit offered in 2022. Three of the extension units we reviewed were able to demonstrate that they consistently followed every step of their processes for approving OPM courses. Only one of the four extension units with an instructor review process could demonstrate that it followed each process step for all of the courses we reviewed. As Table 2 shows, only Davis Extension was able to provide evidence that it followed each step of the process it had established for reviewing both courses and instructors. Santa Barbara Extension followed its established course approval process, but the unit did not have an established instructor review process, as we note earlier. For eight of the 13 courses that we reviewed at the other three extension units, the units either did not follow all of the steps in the processes they had established for reviewing instructors, or were unable to demonstrate that they followed each step. UCLA Extension and Berkeley Extension were able to provide documented approvals for all or most of the OPM courses reviewed, respectively. However, each of the three units was unable to demonstrate that it approved an instructor of at least one of the courses reviewed. Berkeley Extension was unable to provide supporting documentation, such as instructor references, for any of the four courses reviewed. Although San Diego Extension has a policy that describes its approval process, for three of its five courses we reviewed, it could not demonstrate its approval of the courses or the instructors. Because the extension units rely on OPMs to provide courses, extension units’ approvals of courses and instructors are a key safeguard to ensure that courses and instructors meet UC standards and that students receive the quality of instruction they expect.

The three extension units attributed these lapses to staff turnover or poor document retention practices. For example, for one of its boot camps, San Diego Extension’s assistant dean stated that the unit may have overlooked the instructor and course approval because the approval was pending when the assigned program manager departed and he may not have communicated the approval status to the incoming manager. The assistant dean said that to address this issue, San Diego Extension will examine its process to identify possible improvements so that all of its stakeholders know whether the course and instructor have been approved. One of the courses at San Diego Extension that did not have documented approval of the course or instructor was a course conferring credit toward a professional certificate and was subject to Academic Senate regulations that require certain approvals. In this case, the lack of approval for the course puts San Diego Extension out of compliance with Academic Senate regulations, in addition to being noncompliant with its own processes.

Similarly, UCLA Extension’s assistant dean of academic affairs explained that he could not provide evidence that the extension unit followed its process because a previous program director had departed abruptly, leading to the course and instructor approval documents not being properly transferred to the new program director. He said that UCLA Extension has since improved its recordkeeping practices by storing in the unit’s central database all documents related to course and instructor approvals for OPMs, and this practice should allow other staff to access the documents even if program managers leave the unit.

Berkeley Extension could not demonstrate that it followed its established instructor approval process in several instances because it did not retain approval documentation. The contracts we reviewed for Berkeley Extension have been in place for multiple years, and the unit approved the four courses we reviewed before 2019. The assistant dean stated that the unit has since adopted a stronger record retention process and now retains electronically all documents related to course and instructor approvals. By deviating from established processes and regulations for the approval of OPM courses and instructors, UC risks offering students courses that do not meet UC standards and diminishing the value of such courses to students.

Certain Extension Units Did Not Use Student Course Evaluations to Monitor OPM Instruction

The Western Association of Schools and Colleges’ (WASC) Senior College and University Commission has established guidance on agreements with unaccredited entities such as OPMs.4 That guidance states that the accredited institution should, among other things, establish procedures for periodically evaluating the efficacy and quality of the unaccredited entity’s services and the outcomes the entity provides. A 2022 report in the International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education notes that course evaluations are commonly used to measure teaching effectiveness at universities.

At all extension units that we reviewed, staff indicated that students’ course evaluations occurred as part of the typical process for extension unit courses. However, campuses varied in their approach to student course evaluations for OPM courses. San Diego Extension used its own standard course and instructor survey for the OPM courses that we reviewed. In contrast, Davis Extension’s dean explained that its process for student course evaluations varies by OPM and that one OPM performs its own surveys and evaluations, while the unit administers its own course evaluations for the other OPM programs using the same format it follows for other extension unit courses. Berkeley Extension’s program director of business and management stated that one of its OPM partners did not administer student course evaluations and that another OPM manages its own student course evaluations and provides summaries to the campus. The program director also said that Berkeley Extension has begun to implement its own student course evaluations for all of its boot camp courses.

Both Santa Barbara and UCLA extension units stated that their respective OPMs conduct student course evaluations but that the units do not receive regular reports from the OPMs on the evaluations. Santa Barbara Extension’s senior international and business development manager explained that staff meet with OPMs and sometimes discuss these evaluations, but they do not perform a detailed review of the OPMs’ evaluation data. UCLA Extension’s assistant dean of academic affairs acknowledged that the unit does not regularly review the results of the evaluations conducted by the OPMs, although the OPM occasionally shares its results upon request from the extension unit or as needed. Staff at both Santa Barbara and UCLA extension units stated that OPMs have an incentive to ensure student satisfaction and the quality of education they provide to protect their reputations. However, because an OPM’s interests may differ from those of a campus, the unit’s reliance on the OPMs to notify it of concerns may be misplaced. Santa Barbara Extension’s senior international and business development manager acknowledged that there are risks to not performing a detailed review of the evaluations administered by the OPMs but stated that the extension unit trusts the OPMs to inform it if there are problems. UCLA Extension’s assistant dean of academic affairs stated that the extension unit ensures that students of OPM courses know that they have access to the same feedback systems as other students do to file complaints about any problems they experience.

Our survey responses suggest that some students have concerns with courses taught by OPMs that the campuses should address. For example, 111 of 321 survey respondents who answered a question about the coaching, career support services, and other services provided through their OPM programs indicated that they were dissatisfied.5 The text box includes a selection of the students’ responses. In response to another survey question, 216 of 322 students reported that the program or instruction they received did not impact their job situation at all. The potential impact of the course they took on their employment seemed important to many students because 224 of 324 respondents reported that they enrolled in the program they took for the purpose of changing their career or field of work. Because the extension units did not routinely use OPMs’ evaluations to monitor students’ experiences and satisfaction, the units lacked a proven means of identifying ineffective courses and instructors and were consequently less able to take proactive steps to improve outcomes for students.

Examples of Critical Responses From Our Survey

- “The quality of the mentors I worked with was very low. Overall I didn’t get much help from my mentors. The quality of the content was all over the place.”

- “The career support and the availability of content for one year, as promised, was non-existent.”

- “The $10k bootcamp itself taught me about 3 or 4 weeks’ worth of knowledge that I could have gotten for free on YouTube. One of the reasons I did not drop out when I realized the bait and switch scam, was because I was hopeful that the career services would be of use. However, there were no companies ready to hire bootcamp graduates…The program left me severely underprepared and unqualified to work in the field.”

Source: Responses to California State Auditor survey.

Campuses Lack Certain Guidance From the Office of the President on Contracting With OPMs

Key Points

- The selected campuses’ contracts largely aligned with federal rules and guidance regarding incentive compensation. However, some contracts included payment terms that may elevate the risk of OPMs using practices to recruit and enroll students that are not in the best interests of students.

- We identified several instances in which UCs outsourced key services to an OPM, such as admitting students and selecting and hiring course instructors and assistants, despite guidance from the WASC Senior College and University Commission stating that those services are not acceptable to be outsourced.

Campuses Need Additional Guidance About Compensating OPMs to Better Protect Students’ Interests

Although the UC contracts we reviewed with OPMs generally complied with federal law regarding incentive compensation for student recruitment, UC could strengthen its guidance to campuses to better protect students. In order to participate in many federal student aid programs, federal law prohibits institutions, including UC, from providing financial incentives based, in part, on success in recruitment activities, as the text box shows. For example, payments based on success in targeted recruiting, such as directly contacting potential enrollment applicants, are subject to the ban on incentive compensation. Incentive compensation includes tuition revenue sharing, which ties OPMs’ compensation to the number of students whose enrollment results directly from the OPMs’ recruitment activity. The purpose of the prohibition is to protect students against abusive recruiting practices designed to unduly pressure students to enroll in programs that do not meet their needs. The ED allows for a bundled services exception to the prohibition on incentive compensation, as the text box explains.

Incentive Compensation and the Bundled Services Exception

Incentive Compensation

The Higher Education Act of 1965 prohibits institutions from paying any commission, bonus, or other incentive payment based, in part, upon success in securing enrollments, to those engaged in any student recruitment or admission activity (incentive compensation).

Tuition Revenue Sharing

The ED generally considers payments to third parties based on the amount of tuition generated (tuition revenue sharing) to be indirect incentive compensation, which is also prohibited.

Bundled Services Exception

The ED allows for an exception to the prohibition on incentive compensation. Tuition revenue sharing is allowed if, meeting other requirements, such payments are not solely for recruitment services but are also for provision of other services, such as marketing or technology services. This exception is commonly referred to as the bundled services exception.

Source: Federal law and ED guidance.

In alignment with the federal prohibition on incentive compensation, the Office of the President has established guidance on incentive compensation that advises campuses not to enter into any revenue-sharing arrangements with entities, such as OPMs, that recruit undergraduate students. It also suggests that campuses apply the same standard to international students, even though the federal law prohibiting incentive compensation does not apply to the recruitment of international students residing in foreign countries who are not eligible to receive federal student assistance. However, the Office of the President’s guidance does not establish a similar expectation for graduate or continuing education students, which are the student populations affected by the OPM contracts we reviewed.

One extension unit we reviewed, as well as six of 10 graduate programs we reviewed, incorporated contract provisions that acknowledged the incentive compensation ban. In UCLA Extension’s contract with the OPM providing its technology boot camps, each party certified to the other that it complied with all applicable portions of the federal regulation prohibiting incentive compensation. At UC Berkeley and UC Davis, the graduate programs and one contract for online continuing education courses either asserted that the OPMs would compensate employees in accordance with regulations prohibiting incentive compensation or that they complied through the bundled services provision. These provisions are potential best practices because they confirm that both parties involved are aware of their responsibilities to protect students from the undue influence of an incentivized recruiter. However, none of these contracts included methods to monitor compliance or any provisions that indicated that the campuses would assess the OPM’s compliance.

The contracts we reviewed broadly aligned with the bundled services exception, although we question whether certain tuition revenue-sharing arrangements might provide an incentive for the OPMs to recruit more students. For example, the extension units at Berkeley, Davis, UCLA, and San Diego had contracts with the same OPM to provide technology boot camps, and Santa Barbara Extension had a contract with another OPM for similar services. All of these boot camp contracts directed the OPMs to provide instruction and enrollment services, as Table A1 of Appendix A shows, and each involved tuition revenue sharing. The ED’s guidance on incentive compensation does not explicitly state that the bundled services exception is inapplicable when a third party performs instruction. The guidance only states that the third party’s independence from the institution that provides the actual teaching is a significant safeguard against the recruitment abuses the ED has previously seen. Likewise, the ED’s guidance does not state that the bundled services exception is inapplicable when the third party determines enrollments. Instead, it states that when the institution determines enrollments, tuition revenue sharing does not incentivize recruiting as it does when the recruiter is determining enrollment numbers and there is no limitation on enrollment. Accordingly, we are unable to conclude that the contracts in which the OPM performs enrollments for the program violate federal law. Nevertheless, based on the ED’s guidance, the boot camp contracts’ provisions could increase the risk of OPMs engaging in abusive recruiting practices by encouraging them to focus on increasing numbers rather than on offering quality programs to students.

In another instance, we noted that in addition to a tuition revenue-sharing provision, a contract for UCLA’s online Master of Healthcare Administration program provided for a bonus payment that increases based on the OPM’s success in securing specified amounts of tuition revenue, which directly correlates to success in recruiting prospective students. When we questioned the propriety of the bonus, UCLA’s program director described certain safeguards: the program’s enrollment is limited, and UCLA makes all admissions decisions. However, the program’s contract did not specify a cap on enrollment, potentially increasing the risk of using the bonus payment as an incentive to recruit more prospective students. Because ED guidance does not address this specific payment structure, we did not determine whether the scenario violated the incentive compensation prohibition. Nevertheless, the contract terms created a higher risk because they incentivized recruitment in a way that other UC contracts did not by offering a bonus based on enrollments.

Campus personnel generally agreed that guidance from the Office of the President on recruiting protections for the students affected by OPM contracts would be useful. The Office of the President’s director of academic planning and policy acknowledged that there is no UC guidance on recruiting extension students, except to the extent that the existing guidance could apply to international students who have enrolled in extension unit programs. Because the Office of the President has already established guidance for recruiting international students that exceeds federal requirements, it should consider expanding its guidance to graduate and continuing education students. The Office of the President’s executive director of graduate studies agreed that it would be prudent to mitigate any potential recruiting risks to graduate students by offering guidance, although she described needing flexibility to determine which of the existing recruiting guidelines would be best for graduate students. The extension unit staff we spoke with were generally receptive to or supportive of additional guidance in this area. Without guidance regarding incentive compensation related to graduate and extension studies, UC risks not complying with federal requirements and, more importantly, risks creating situations in which OPMs might be inclined to focus more on recruiting students than providing quality instruction, such as by omitting or providing misleading information about the programs, as we discuss in Table 1.

UC’s Use of OPMs Does Not Align With Best Practices for Contracting With Unaccredited Entities

WASC’s Senior College and University Commission, the entity from which the UC receives its accreditation as an educational institution, has established a policy on accredited institutions, such as the UC, contracting with unaccredited entities, such as the OPMs we reviewed. It has also issued guidance on how to implement this policy, and that guidance describes certain best practices for contracting with unaccredited entities and specifies services that accredited institutions should or should not outsource. These best practices help safeguard the institution, which bears final responsibility for ensuring the quality and integrity of all activities conducted in its name.

WASC’s Senior College and University Commission guidance establishes principles for contracting with unaccredited entities, specifies elements that should be included in the agreement, and specifies services that are acceptable to outsource. The guidance states that the four services described in the text box are among those services that accredited institutions should not outsource to unaccredited entities, although the guidance also recognizes that there may be exceptions that merit additional consideration. Nevertheless, we identified OPMs performing each of these functions for the UC. In our review of 30 contracts, we found that OPMs were responsible for admitting students into OPM courses in 16 instances and, as Table A1 in Appendix A shows, OPMs were responsible for collecting tuition in 17 instances. WASC guidance also notes that selection of and hiring of instructors should not be outsourced. However, we found that for the 15 contracts we reviewed that included OPM instruction, OPMs were required to select instructors in 14 contracts and required to hire instructors in 13. Moreover, some institutions could not provide records related to student completion of OPM-instructed courses and instead rely on OPMs to maintain records of student performance.

Key Services That Institutions Should Not Outsource

• Admitting students

• Maintaining records of student performance

• Selecting and hiring course instructors and assistants

• Collecting tuition or other fees directly from students to compensate for an outside vendor’s services

Source: Agreements with Unaccredited Entities Guide from the Senior College and University Commission of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges.

We did not identify any systemwide guidance established by the Office of the President on how best to contract with an OPM or that specified which functions could be outsourced. According to a WASC Senior College and University Commission representative, the Commission intended the guidance for accredited entities to have a broad applicability for all agreements with unaccredited entities; it was not exclusively for those programs that result in academic credit. As we note throughout this report, outsourcing educational services to OPMs without adequate oversight can increase the risk of misrepresentation, misguided recruiting practices, and educational programs that fall short of students’ expectations to enhance their knowledge, skills, and employability.

Other Areas We Reviewed

During the course of our audit, we identified concerns pertaining to updates to federal incentive compensation guidance and the revenue amounts Berkeley Extension received from an OPM. We also reviewed student completion rates for OPM-instructed education programs and the processes campuses used when entering into OPM contracts.

Updates to U.S. Department of Education Incentive Compensation Guidance