2023-102.2 Homelessness in California

San José and San Diego Must Do More to Plan and Evaluate Their Efforts to Reduce Homelessness

Published: April 9, 2024Report Number: 2023-102.2

April 9, 2024

2023-102.2

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee requested an audit of the State’s homelessness funding, including an evaluation of the efforts undertaken by the State and two cities to monitor the cost‑effectiveness of such spending. We published a separate report (2023‑102.1) that details our findings related to the State’s activities. This report (2023‑102.2) focuses primarily on the activities of the two cities we reviewed, San José and San Diego, and it concludes that the cities must do more to better evaluate their efforts to reduce homelessness.

San José and San Diego identified hundreds of millions of dollars in spending of federal, state, and local funding in recent years to respond to the homelessness crisis. However, neither city could definitively identify all its revenues and expenditures related to its homelessness efforts because neither has an established mechanism, such as a spending plan, to track and report its spending. The absence of such a mechanism limits the transparency and accountability of the cities’ uses of funding to address homelessness.

Although both cities provide tens of millions of dollars for homelessness programs and services through agreements with external service providers, such as nonprofits, neither city evaluated the effectiveness of its agreements. San Diego has generally established clear performance measures, such as specifying the number of people the service provider will assist, to enable it to assess whether the providers’ efforts are an effective use of funds. However, San José has not consistently done so. Furthermore, neither city has evaluated the effectiveness of the programs it provides to address the profound health and safety risks associated with unsheltered homelessness.

Both cities use interim housing as a way to provide shelter for people experiencing homelessness, but they both need to develop additional permanent housing. Data consistently show that placements into permanent housing results in significantly better outcomes than placements into interim housing. The cities have each made efforts to develop additional interim and permanent housing; however, neither has a clear, long‑term plan to ensure that they have the housing necessary.

We recommend that San José and San Diego each publicly report on all of their homelessness funding, assess the effectiveness of their spending, and better plan to meet their permanent housing needs.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| Cal ICH | California Interagency Council on Homelessness |

| CoC | Continuum of Care |

| ERF | Encampment Resolution Funding |

| ESG | Emergency Solutions Grant |

| state data system | Homeless Data Integration System |

| HHAP | Homeless Housing. Assistance and Prevention |

| HMIS | Homeless Management Information System |

| HSSD | Homelessness Strategies and Solutions Department |

| HUD | U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development |

| NPD | Neighborhood Policing Division |

| PIT count | point-in-time count |

| VASH | Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing |

SUMMARY

The Joint Legislative Audit Committee requested an audit of the State’s homelessness funding, including an evaluation of the efforts undertaken by the State and two cities to monitor the cost effectiveness of such spending. Separately, we published a report (2023‑102.1) that focuses primarily on the State’s activities to address homelessness. In this report (2023‑102.2), we present our findings and conclusions regarding the two cities we reviewed: the city of San José (San José) and the city of San Diego (San Diego).

Since 2015 both San José and San Diego have seen increases in the number of individuals experiencing homelessness. In response, the cities have dedicated hundreds of millions of dollars in federal, state, and local funding to preventing and ending homelessness. In this audit, we reviewed the cities’ spending and their efforts to evaluate the effectiveness of the programs they funded, and we drew the following conclusions:

San José and San Diego Have Adopted Plans for Addressing Homelessness but Do Not Completely Report on All of Their Homelessness Funding

Both San José and San Diego identified hundreds of millions of dollars in spending on programs to prevent and end homelessness in recent years. Nonetheless, neither city could definitively identify all its revenues and expenditures related to its homelessness efforts because the cities have not established a mechanism, such as a spending plan, to track and report their spending. Such a mechanism would increase transparency and accountability regarding the cities’ use of homelessness funds. Further, it might enable the cities to better align their spending with the action plans they follow. While San Diego has a city‑specific action plan that details its goals and the services it intends to provide, San José has historically followed a broader regional action plan and has only recently identified the specific steps it will take to implement that regional plan.

Neither San José nor San Diego Has Consistently Evaluated the Effectiveness of Its Homelessness Programs

Both San José and San Diego spend tens of millions of dollars on agreements with external service providers, such as nonprofits, to provide homelessness programs and services. Although San Diego has generally established clear performance measures to assess whether these efforts are an effective use of funds, San José has not consistently done so. In addition, neither San José nor San Diego has evaluated the effectiveness of these agreements or of other city‑provided programs that address the profound health and safety risks associated specifically with unsheltered homelessness.

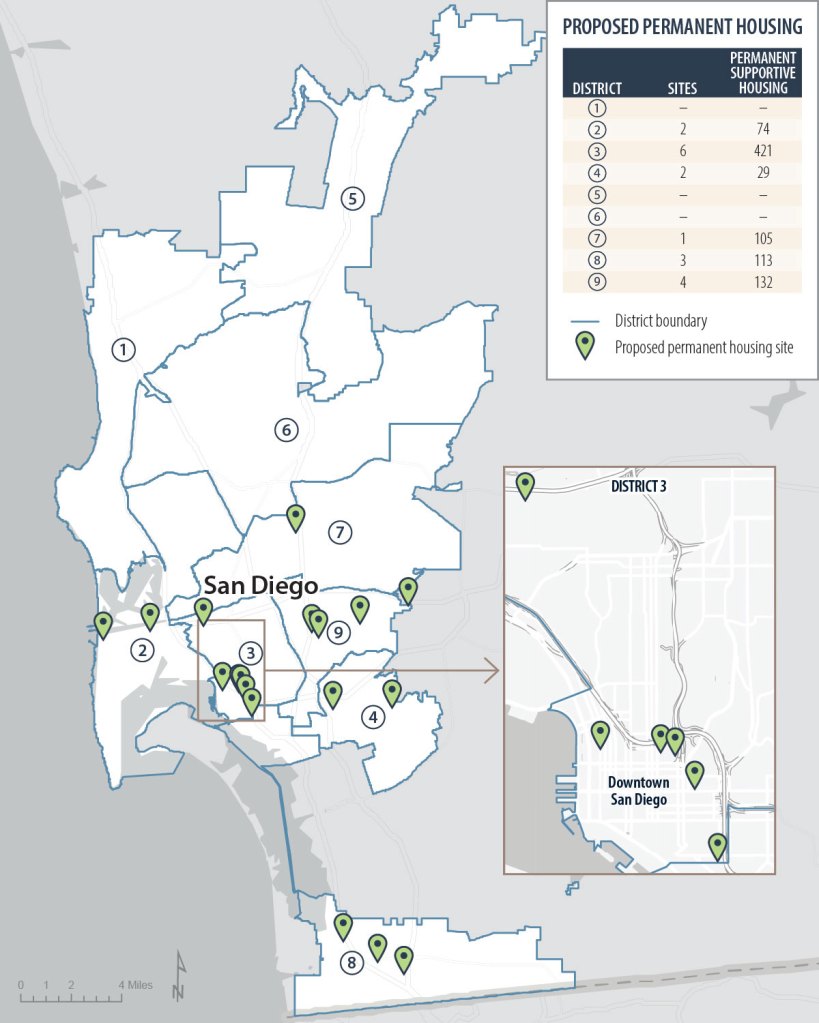

To Better Address Homelessness, San José and San Diego Will Need to Develop Additional Interim and Permanent Housing

Data consistently show that placing individuals who are experiencing homelessness into permanent housing results in significantly better outcomes than placements into interim housing. Nonetheless, interim housing plays a critical role in providing shelter to people who need it. In recent years, both San José and San Diego have taken steps to develop additional interim housing sites. However, neither city currently has the shelter capacity it requires to house its residents who are experiencing unsheltered homelessness. Moreover, although the two cities have made efforts to develop additional permanent housing, neither has a clear, long‑term plan to ensure that it has the housing necessary to support individuals who require it.

Agency Comments

The city of San José provided additional context it asserted was lacking in the report, but the city generally agreed with our recommendations and has indicated the steps it plans to take to implement them.

The city of San Diego generally agreed with the recommendations and indicated that it will take appropriate steps to implement them where feasible.

Although we did not make recommendations to the San Diego Housing Commission, it disagreed with some of our findings and conclusions.

INTRODUCTION

Background

The number of people experiencing homelessness in the State has increased significantly during the last 10 years. According to federal regulations, any individual or family who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence is experiencing homelessness. When people primarily spend their nights in public or private locations not normally used for sleeping, it is considered unsheltered homelessness. When people stay in emergency shelters, transitional housing programs, or safe havens, it is considered sheltered homelessness. People experiencing homelessness face devastating challenges to their health and well‑being. For example, a study found that two‑thirds of participants reported current mental health symptoms and that homelessness worsened participants’ mental health symptoms.

To identify the number of people experiencing homelessness, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) requires annual point‑in‑time (PIT) counts of those experiencing sheltered homelessness and biennial counts of those experiencing unsheltered homelessness. Figure 1 shows that although the number of people experiencing homelessness in California decreased slightly from 2013 through 2015 to fewer than 116,000 individuals, it has increased to more than 181,000 individuals as of 2023.

Figure 1

California’s Population of People Experiencing Homelessness Has Increased Since 2013

Source: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) point‑in‑time (PIT) counts, Annual Homeless Assessment Report, and HUD memorandum.

Note: HUD requires Continuums of Care (CoCs) to conduct a PIT count of people experiencing sheltered homelessness annually and a count of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness at least biennially. To present the total number of people experiencing homelessness, we therefore used the year in which both categories of PIT counts were conducted.

* HUD waived the PIT count requirement for unsheltered homelessness in 2021 because of the COVID‑19 pandemic, but it required the count again in 2022.

Figure 1 description: Figure 1 is a bar graph that depicts the number of people experiencing homelessness in California generally increasing since 2013 through to 2023. The bar graph is a stacked bar which depicts the total count of people experiencing homelessness with two different colors in the bars. The blue-gray colored section of the bars represent the counts of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness in a given year and dark blue colored sections of the bars represent the count of people experiencing sheltered homelessness in the same year. Each bar also lists the actual count within each category of homelessness culminating with the total count for that year presented on top of the bar. For example, in the bar for year 2013, the dark blue section has a count of 45,554 and the blue-gray section has a count of 72,998, and therefore the total count for that whole 2013 bar is 118,552. The years represented in the bar graph include 2013, 2015, 2017, 2019, 2022, and 2023. There was a slight decrease in the total count of people experiencing homelessness from 2013 to 2015, but the count has since continued to grow. Below the bar graph is a list of sources used and some notes further explaining where the count data originated and how we calculated total counts.

Figure 2 shows the three main phases of homelessness: entering homelessness, experiencing homelessness, and exiting homelessness. The University of California, San Francisco’s June 2023 study of people experiencing homelessness describes economic, social, and health factors that can lead to homelessness. The study found that high housing costs and low incomes had left participants vulnerable to homelessness and that the most frequently reported economic reason for entering homelessness was loss of income. Resolutions to this situation include preventing people from entering homelessness and helping people exit homelessness to live in permanent housing. Factors such as scarcity of housing, high cost of housing, lack of rental subsidies, and lack of assistance in identifying housing create barriers to accessing housing.

Figure 2

The Three Phases of Homelessness Each Have Mitigating Solutions

Source: Federal regulations, Federal Strategic Plan, Business, Consumer Services, and Housing Agency documentation, and Toward a New Understanding: The California Statewide Study of People Experiencing Homelessness, a study published by the University of California San Francisco Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative in June 2023.

Figure 2 description: Figure 2 is an image depicting how one person experiences the three phases of homelessness. In the first third of the figure, a person is depicted as losing their housing and entering homelessness. This part of the image also lists the methods by which this could have been prevented. The middle part of the figure depicts the same person sleeping on the ground outside and experiencing homelessness. This part of the image also lists the methods that programs can employ to mitigate the impacts of experiencing this unsheltered homelessness. The last part of the figure shows the same person finding permanent housing and exiting homelessness. This part of the image also lists the methods that programs could use to help achieve this outcome.

Numerous Entities Have Roles in Funding Homelessness Services in California

Numerous entities are involved in funding homelessness prevention, homelessness support services, and the provision of permanent housing in California. Federal, state, and local governments all issue funding that flows through other entities before reaching people at risk of or experiencing homelessness. Most notably, the State recently increased its financial role in addressing housing affordability and homelessness. According to the Legislative Analyst’s Office, the State allocated nearly $24 billion to addressing homelessness and housing affordability during the last five fiscal years, from fiscal years 2018–19 through 2022–23.

As Figure 3 shows, Continuums of Care (CoCs) are central to California’s provision of homelessness services. In 1993 HUD established the CoC system. Formed according to federal regulations to achieve the goal of ending homelessness within a geographic area, each CoC is a group of individuals and entities that may include homelessness service providers, cities, and counties. Congress codified the CoC system into law to provide federal funding for states, local governments, and nonprofit service providers to quickly rehouse people experiencing homelessness.

Figure 3

There Are Many Layers to Homelessness Funding and Services

Source: State law; grant agreements; documentation from the California Interagency Council on Homelessness (Cal ICH), HUD, California Department of Social Services, California Department of Housing and Community Development, cities and counties; and a service provider’s website.

Figure 3 description: Figure 3 is an organizational chart that depicts the many agencies involved in homelessness funding and services and how the funding flows through these agencies to eventually reach people experiencing or at risk of experiencing homelessness through the provision of services. There are arrows connecting all the layers which depict either the flow of funding through solid green colored arrows or the flow of services through dotted arrows. At the top layer of the figure are images representing the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the government of the State of California. As shown through solid green colored arrows, HUD provides funding to the State as well as directly to Continuums of Care (CoCs) and entities within CoCs. The State also provides funding to CoCs and entities within CoCs, also shown through the directions of solid green arrows. The middle layer of the chart depicts CoCs and entities within CoCs, specifically Counties and Cities, receiving funding from HUD and the State. The middle layer of the chart also depicts Nonprofit Homelessness Service Providers within CoCs receiving funding from HUD, Counties, and Cities, also shown through the directions of solid green arrows. The last layer of the figure depicts Nonprofit Homelessness Service Providers giving funding to subcontractors shown by the direction of a solid green arrow as well as providing services directly to people at risk of or experiencing homelessness shown by the direction of a dotted arrow. The last layer also shows people at risk of or experiencing homelessness receiving services from the cities and counties directly as well, which are again shown by the directions of dotted arrows.

California has 44 CoCs that cover its 58 counties. Each CoC enables collaboration among member entities in its area but does not direct the actions of those member entities. The State and HUD provide funding through a variety of programs to CoCs and the entities within CoCs, such as counties, cities, and nonprofits. Those entities are responsible for following the eligible uses and reporting requirements of the funding they receive.

Data show that nearly 316,000 individuals experiencing homelessness accessed housing and services in California’s 44 CoCs in 2022.1 The COVID‑19 pandemic, which occurred during the period we reviewed, profoundly affected individuals at risk of or experiencing homelessness and resulted in both the federal and state governments dedicating substantial funding to addressing the crisis.

San José and San Diego Provide Homelessness Services Through Multiple Departments

We reviewed two cities as part of our audit. The Joint Legislative Audit Committee specifically requested that we review the city of San José (San José). For the second city, we selected the city of San Diego (San Diego) based on its population, its geographic location, the number of people in it experiencing homelessness, and its available funding to reduce homelessness, among other factors. Both San José and San Diego operate as member entities of their respective CoCs, which also have responsibilities for the people experiencing homelessness in each city. The cities should spend the funding they receive as effectively as possible to meet the needs of their residents.

San José

Located in the San Francisco Bay Area in Santa Clara County, San José had nearly 1 million residents as of July 2022. It operates as a council‑manager form of government. Its city council consists of one representative from each of the 10 council districts and a mayor. The council determines all matters of policy for the city. The city manager serves as the city’s chief administrative officer and directs and supervises the administration of all city departments, offices, and agencies. The number of people experiencing both sheltered and unsheltered homelessness in San José increased from 2015 through 2022, as Figure 4 shows. However, San José saw a slight drop in the number of people experiencing homelessness from 2022 to 2023.

Figure 4

The Number of People Experiencing Homelessness in San José Has Increased Since 2015

Source: City homelessness PIT count data.

Note: HUD requires CoCs to conduct PIT counts of people experiencing sheltered homelessness annually and of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness at least biennially. To present the total number of people experiencing homelessness, we used the year in which both categories of PIT counts were conducted.

* HUD waived the PIT count requirement for unsheltered homelessness in 2021 because of the COVID‑19 pandemic, but it required the count again in 2022.

Figure 4 description: Figure 4 is a bar graph that depicts the number of people experiencing homelessness in San Jose, California generally increasing from 2015 to 2023. The bar graph is a stacked bar which depicts the total count of people experiencing homelessness with two different colors in the bars. The blue-gray colored section of the bars represent the counts of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness in a given year and dark blue colored sections of the bars represent the count of people experiencing sheltered homelessness in the same year. Each bar also lists the actual count within each category of homelessness culminating with the total count for that year presented on top of the bar. For example, in the bar for year 2015, the dark blue section has a count of 1,253 and the blue-gray section has a count of 2,810, and therefore the total count for that whole 2015 bar is 4,063. The years represented in the bar graph include 2015, 2017, 2019, 2022, and 2023. There was a slight decrease in the total count of people experiencing homelessness from 2022 to 2023. Below the bar graph is a list of sources used and some notes further explaining where the count data originated and how we calculated total counts.

As we show in Figure 5, multiple city departments have roles in San José’s efforts to address homelessness. These departments operate under the direction of the city council, the city manager, and a deputy city manager, whom the city manager appointed in 2022 to focus on addressing homelessness. Some departments’ work involves city staff directly providing homelessness services. For example, the fire department responds to incidents at encampments, and the Parks, Recreation and Neighborhood Services’ BeautifySJ program collects trash from encampment areas and performs abatements when necessary.2 However, the city also supplies grant funding to external service providers, such as nonprofits, that provide rental assistance, housing searches, and other services. Finally, the city funds the development of interim and permanent housing.

Figure 5

Several Entities Are Involved in Homelessness Efforts in San José

Source: San José’s organizational chart in its adopted budget, website, City Charter, Municipal Code, City Council memo, and an interview with city staff.

Figure 5 description: Figure 5 is an organizational chart which depicts the several entities involved in efforts to address homelessness in San Jose and brief descriptions of their respective authority. The top of the chart shows two major entities, the County of Santa Clara and the city of San Jose. Santa Clara County works with the city of San Jose government to end homelessness. Within the city government structure, the city council and mayor set city policies that flow down to the city manager’s office, which includes the deputy city manager for homelessness. The city manager’s office then works to implement the council and mayor’s policies through oversight of city departments. Some of the departments depicted as receiving this oversight related to the city’s homelessness efforts include the Housing Department and the Parks, Recreation and Neighborhood Services Department. Finally, the end of the organizational flow chart is an arrow that symbolizes that city departments can engage with external service providers who provide direct services to the community.

In addition to the state and federal funding San José receives for homelessness services and affordable housing, the city also uses local tax revenue for these purposes. In 2020 voters in San José approved Measure E—a real property transfer tax imposed on properties priced at $2 million or more—to fund any city purpose. Although the city council’s spending priorities for Measure E have changed over the years, its 2023 adopted priorities required that it use 10 percent of the funding on homelessness prevention, gender‑based violence programs, legal services, and rental assistance. The spending priorities required that it use another 15 percent primarily on homelessness support programs, including shelter construction and operations.

When implementing its efforts to address homelessness, San José works closely with Santa Clara County. The county serves as the CoC’s Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) lead agency.3 The county’s responsibilities also include creating and operating a coordinated assessment system that helps identify the best housing intervention for each person and monitoring the performance of jurisdictions within the CoC. With nearly 1 million residents, San José has over half of the population in Santa Clara County and its CoC’s area; thus, the city’s efforts are crucial to its CoC’s ability to reduce and end homelessness.

San Diego

Located on the southern California coast, San Diego had nearly 1.4 million residents as of July 2022. It operates as a strong mayor form of municipal government. Under this form of government, the mayor is the chief executive of the city and has significant authority over the city’s operations. The city has seen a recent increase in the number of its residents experiencing homelessness, as Figure 6 shows.

Figure 6

The Number of People Experiencing Homelessness in San Diego Has Increased Since 2015

Source: CoC PIT count data.

Note: HUD requires CoCs to conduct PIT counts of people experiencing sheltered homelessness annually and of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness at least biennially. To present the total number of people experiencing homelessness, we used the year in which both categories of PIT counts were conducted.

* HUD waived the PIT count requirement for unsheltered homelessness in 2021 because of the COVID‑19 pandemic, but it required the count again in 2022.

Figure 6 description: Figure 6 is a bar graph that depicts the number of people experiencing homelessness in San Diego, California generally increasing from 2015 to 2023. The bar graph is a stacked bar which depicts the total count of people experiencing homelessness with two different colors in the bars. The blue-gray colored section of the bars represent the counts of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness in a given year and dark blue colored sections of the bars represent the count of people experiencing sheltered homelessness in the same year. Each bar also lists the actual count within each category of homelessness culminating with the total count for that year presented on top of the bar. For example, in the bar for year 2015, the dark blue section has a count of 2,773 and the blue-gray section has a count of 2,765, and therefore the total count for that whole 2015 bar is 5,538. The years represented in the bar graph include 2015, 2017, 2019, 2022, and 2023. There was a decrease in the total count of people experiencing homelessness from 2017 to 2022, after which the count increased again. Below the bar graph is a list of sources used and some notes further explaining where the count data originated and how we calculated total counts.

As Figure 7 describes, San Diego’s efforts to address homelessness involve multiple entities. The San Diego Housing Commission (housing commission) is the primary entity responsible for administering most of San Diego’s homelessness programs. The city created the housing commission and, with some exceptions, granted it all rights, powers, and duties of a housing authority.4 The Housing Authority of the City of San Diego (housing authority)—composed of the nine members of San Diego’s city council—governs the housing commission. In addition, the city officially established in its municipal code its Homelessness Strategies and Solutions Department (HSSD) effective February 2022. HSSD is responsible for planning, developing, and overseeing a comprehensive network of citywide programs that provide immediate assistance and long‑term solutions to meet the needs of those experiencing homelessness. This includes handling the city’s homelessness program funding and overall management of the city’s homelessness efforts. HSSD also administers some of the city’s homelessness programs; however, the housing commission administers most programs through a memorandum of understanding with the city.

Figure 7

Several Entities Are Involved in Efforts to Address Homelessness in San Diego

Source: State law, San Diego’s municipal code, charter, resolutions, memorandums of understanding, organizational chart, and Independent Budget Analyst; the housing commission; and the Regional Task Force.

* The housing authority is a separate legal entity from the city. The housing commission is a public agency of the housing authority.

Figure 7 description: Figure 7 is an organizational flow chart which depicts the several entities involved in efforts to address homelessness in San Diego and brief descriptions of their respective authority. The chart has three major entities at the top of the figure: the San Diego Regional Task Force on Homelessness, the city of San Diego, and the Housing Authority. Both the Regional Task Force and the Housing Authority are depicted as working together with the city of San Diego to end homelessness. Within the depiction of the city government structure, there is a mayor that oversees city departments and a city council which sets city policy and allocates funding to city departments. Some of the departments depicted as receiving this oversight and funding to address homelessness include the San Diego Police Department and the Homelessness Strategies and Solutions Department. Within the depiction of the housing authority structure, the figure shows that the same nine members of the city of San Diego city council are also the nine members of the Housing Authority, but also explains that the city and the housing authority are still two separate legal entities. The housing authority is depicted as governing another entity known as the San Diego Housing Commission. The last part of the organizational flow chart shows that the housing commission and city departments work together to address homelessness in the city through a memorandum of understanding.

The city is a member of the San Diego City and County CoC. The lead agency for this CoC is the Regional Task Force on Homelessness (Regional Task Force), a nonprofit organization. The Regional Task Force performs a variety of functions related to San Diego’s homelessness efforts, such as conducting PIT counts of the individuals experiencing homelessness in the city.

ISSUES

San José and San Diego Have Adopted Plans for Addressing Homelessness but Do Not Completely Report on All of Their Homelessness Funding

Neither San José nor San Diego Has Consistently Evaluated the Effectiveness of Its Homelessness Programs

To Better Address Homelessness, San José and San Diego Will Need to Develop Additional Interim and Permanent Housing

San José and San Diego Have Adopted Plans for Addressing Homelessness but Do Not Completely Report on All of Their Homelessness Funding

Key Points

- Neither San José nor San Diego tracks and reports in one location, such as a spending plan, all of its funding and spending related to homelessness. The cities’ fragmented reporting limits public transparency and accountability for hundreds of millions of dollars in state, federal, and local funding. It also impedes the cities’ ability to assess the effectiveness of their spending.

- San José did not develop a plan with city‑specific goals for reducing homelessness until January 2024. As a result, it has struggled to evaluate the effectiveness of its actions.

- San Diego established a city‑specific plan for reducing homelessness in 2019. This plan identifies clear strategies and goals that have enabled San Diego to prioritize the needs of its residents who are experiencing homelessness. The city recently updated its goals to reflect changing conditions.

Neither San José nor San Diego Centrally Tracks and Reports Its Spending on Homelessness Efforts

Both San José and San Diego identified hundreds of millions of dollars in spending of federal, state, and local funding to respond to the homelessness crisis over the last three years. However, neither city has established a method—such as a spending plan—for collecting and tracking in a central location information about the homelessness funding it receives and spends. As a result, the cities lack the information necessary to easily assess the effectiveness of their spending. Further, by not providing comprehensive funding and spending information to the public and policymakers, the cities have limited transparency and accountability.

In our attempt to create a complete list of their homelessness funding and spending, we worked extensively with the two cities to develop methods to identify from their accounting records the amounts they had received and spent on homelessness efforts from fiscal year 2020–21 through 2022–23. In the absence of an independent source to verify the amounts of homelessness funding the cities received and spent, we relied upon each city to ensure that they accurately identified the information they provided to us. Therefore, we could not validate the accuracy and completeness of these amounts. During the three‑year period of our review, the cities were each awarded federal and state grant funding for which they had to apply, as well as federal stimulus funding. Each funding source typically has a deadline by which the cities must spend the funding. Each source also has established eligible uses for the funding, which Appendix A lists. In addition to the federal and state funding they received, both cities allocated local funds for homelessness purposes. For example, San José allocated some Measure E funding for homelessness, as we discuss in the Introduction.

Table 1 shows the aggregate amounts of federal, state, and local funding that San José identified that it had received or allocated for its homelessness efforts in the past three fiscal years. As the table shows, at the end of fiscal year 2022–23, San José had more than $13 million remaining of the federal funding and more than $53 million of the state funding it had received. About $46 million of that remaining funding related to two statewide programs: Homekey and the Homeless Housing, Assistance and Prevention Program (HHAP). The State awarded Homekey funding to San José for specific projects that involve remodeling hotels and motels to create housing. In contrast, San José can use HHAP funding for a number of purposes, which we list in Appendix A. The spending deadlines for both programs are still years away. In fact, the State allocated San José more than $55 million in additional HHAP funding for Rounds 4 and 5 that it had not yet received during our audit period.

At the end of fiscal year 2022–23, San José also had more than $86 million remaining of the local funds that it had budgeted that year for homelessness purposes. This amount includes its Measure E funding. Some local appropriations are multi‑year appropriations and therefore have remaining balances. Table 1 identifies the purposes for which the city budgeted that funding. Over the last three fiscal years, the city spent more than $20 million in Measure E funding for purposes related to homelessness. It spent 69 percent of this amount—or about $14 million—in fiscal year 2022–23.

Table 2 similarly shows the aggregate amounts of federal, state and local funding that San Diego identified that it had received or allocated for its homelessness efforts in the past three fiscal years. At the end of fiscal year 2022–23, San Diego had more than $52 million in funding designated for homelessness efforts still available. The State also allocated San Diego additional HHAP funding—about $52 million—that it had not received during our audit period. From fiscal year 2020–21 through 2022–23, San Diego spent more than $87 million of its local funding for homelessness purposes. However, the city does not roll over unspent amounts from local funds, so the table does not include a remaining balance for these funds.

Nonetheless, neither San José nor San Diego could definitively identify all the revenues and expenditures related to its homelessness efforts. This limitation is in part because their city departments budget for and track homelessness funding in a variety of ways. For example, some departments receive a budget for homelessness services and track that spending so it is clearly distinguishable. However, other departments commingle in a single fund their budget for addressing homelessness with funding for other purposes, such as the BeautifySJ program. In these instances, the cities cannot distinguish the amounts intended for addressing homelessness. Although these types of challenges primarily involve local funding, cities can also use some state and federal funding sources for more than just homelessness‑related efforts. If cities do not carefully track their usage of these funds for homelessness‑specific expenditures, it may impede their ability to identify all of their homelessness‑related spending.

To inform decision‑makers and provide transparency, the cities should track and report in a single location all funding they receive and use to reduce homelessness. Tracking this funding will require the cities to create and document a methodology for identifying from their financial systems the amounts of homelessness funding they have received, budgeted, and spent. As part of this process, the cities should develop a spending plan for their homelessness funding that identifies the available funding and how they intend to allocate that funding. For example, the cities could identify the amounts of funding they have available from federal, state, and local sources each year and indicate the amounts of that funding they plan to allocate to specific homelessness‑related activities, such as developing permanent supportive housing or conducting outreach. The cities should then report on their spending at the end of each year. San Diego’s independent budget analyst’s office acknowledged that the city needs such a plan when it wrote, “Having a clear, publicly available spending plan enables the Council and the public to monitor program expenses, ensure that existing funds are being maximized, and provides transparency regarding the city’s efforts to address homelessness.”

San José Did Not Develop a City‑Specific Plan for Addressing Homelessness Until January 2024

Careful planning is critical to ensuring that a city’s efforts to address the complex problem of homelessness are effective. As we discuss in the previous section, the cities should develop spending plans to ensure that they maximize their funds and to provide transparency regarding their efforts to address homelessness. However, in addition to spending plans, the cities should also develop action plans with city‑specific goals that identify the actions they will take to address homelessness. This type of plan enables a city to track its progress and evaluate the effectiveness of the actions it takes to achieve its goals.

San José has historically relied on the county‑level community action plan (county plan) to guide its efforts to address homelessness. A committee led by the Santa Clara County CoC developed the 2020–2025 county plan. The director of San José’s housing department was a member of the county plan’s steering committee, and San José had two additional members involved in the county plan’s workgroup to gather community input. The text box lists the county’s homelessness‑related goals.

The County Plan’s Five Goals for 2025:

- Achieve a 30 percent reduction in annual inflow of people becoming homeless.

- House 20,000 people through the supportive housing system.

- Expand the Homelessness Prevention System and other early interventions to serve 2,500 people per year.

- Double interim housing and shelter capacity to reduce the number of people sleeping outside.

- Address the racial inequities present among unhoused people and families and track progress toward reducing disparities.

Source: County plan 2020–2025.

Although we recognize the value of the county plan, we are concerned that the city council did not adopt a city‑specific plan for implementing the county plan (implementation plan) until recently. As a consequence, San José lacked the city‑specific information necessary to assess and, if necessary, adjust its actions to ensure their effectiveness in meeting the specific needs of the city’s residents who were experiencing homelessness. For example, in 2021 and 2022, San José’s housing department submitted memos to the city council regarding the city’s spending priorities for its homelessness programs. However, those memos do not include forward‑looking, measurable goals for the programs. Consequently, the city may not know if its spending and actions met its needs.

In addition, in the absence of a city‑specific implementation plan, the city has not assessed the effectiveness of its actions in achieving the county’s larger goals. Although the city included program‑specific targets in some grant agreements with service providers, it did not identify or report on how these targets helped or would help it achieve the county plan’s larger goals. For example, in fiscal year 2022–23, San José’s housing department approved spending $8 million in Measure E funds on the city’s homelessness prevention system. The city’s 2022–23 amendment to the agreement with a nonprofit for that system specifies that the city’s target was to assist 900 people in staying housed and prevent them from entering homelessness. However, it is unclear how this target specifically fits within the county plan’s goal to achieve a 30 percent reduction in the annual inflow of people becoming homeless because the target does not specify the total number of people the city needs to prevent from entering homelessness to help achieve the 30 percent reduction. The city auditor reached a similar conclusion in a 2023 audit, reporting that the city’s homelessness and housing measures lacked context that would relate them to the broader goals of the county plan.

City staff explained that San José did not develop a city‑specific implementation plan for the county plan until recently because the city was focusing its efforts on responding to the COVID‑19 pandemic. However, the city reported that it took many homelessness‑related actions in those years. Having an implementation plan with clear goals would have helped the city to evaluate the effectiveness of its actions and measure its progress toward its goals.

In December 2023, after we began our review, the city presented an implementation plan to its housing commission. In January 2024, the city council approved that plan. The new implementation plan establishes a direct tie with the county plan, creates accountability by linking the city’s actions to specific departments, and includes measureable outcomes for the city to report publicly on an annual basis. By establishing accountability and transparency, the implementation plan should better situate the city to evaluate the effectiveness of its future actions to address homelessness.

In 2019 San Diego Established a City‑Specific Plan That Includes Clear, Measurable Goals

To reduce and prevent homelessness, San Diego has followed a city‑specific community action plan (city action plan) since 2019. The Corporation of Supportive Housing (CSH)—a national nonprofit organization focused on homelessness and housing—authored this plan in partnership with a steering committee consisting of the city, the housing commission, and the Regional Task Force. The plan identifies the need to set targeted goals and implement a systemwide strategic approach to achieve those goals. It also includes analyses of multiple data sources, including demographic characteristics of people experiencing homelessness, current shelter capacity, permanent housing units, and available financial resources for homelessness.

The city action plan identifies five distinct strategies for addressing homelessness, which the text box presents. Each strategy identifies specific target priorities. For example, to increase the production of and access to permanent housing, the plan prioritizes planning for the development of 3,500 units of permanent supportive housing over 10 years. For each of these longer‑term priorities, the city identifies related actions, including the need to establish annual development targets, create a funding pipeline, implement policy changes, and work with partners to coordinate the implementation of those changes.

The Five Strategies in San Diego’s Action Plan:

- Implement a systems‑level approach to homeless planning.

- Create a client‑centered homeless assistance system.

- Decrease inflow into homelessness by increasing prevention and diversion.

- Improve the performance of the existing system.

- Increase the production of and access to permanent solutions.

Source: The housing commission.

The plan also includes clear goals to allow San Diego to track its progress and evaluate the effectiveness of its actions. The housing commission maintains public dashboards on the city’s progress toward some of its strategic goals. The public dashboards display updates on goals within reach in the next three years, performance data related to the implementation of the strategic goals, and progress toward housing goals. For example, to measure its progress of ending veteran homelessness, San Diego used Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (VASH) voucher utilization rates, among other metrics. San Diego’s dashboard data showed that in each year since 2019, San Diego has issued more of the VASH rental assistance vouchers it received from HUD to veterans experiencing homelessness, increasing its utilization rate from 86 percent in 2019 to 93 percent in 2022. Table 3 describes San Diego’s progress toward achieving selected goals since 2019.

San Diego has revisited its goals and updated them to reflect changes in recent years. In 2023 CSH used newly available data, trends, and resources to update the city action plan’s housing and prevention goals, as well as its financial modeling estimates of required funding to meet those goals. For example, it increased the shelter goal from 390–580 beds to 465–920 beds. The updated plan shows that the number of individuals entering homelessness has increased since 2019, when the city adopted the plan and determined the need for more homelessness prevention actions. Because San Diego recently updated its action plan goals in fall 2023, it is too early to evaluate its progress toward meeting the new goals.

Neither San José nor San Diego Has Consistently Evaluated the Effectiveness of Its Homelessness Programs

Key Points

- San José and San Diego spend millions of dollars annually on services to address homelessness that are provided through agreements with external providers, such as nonprofits. However, the cities have not consistently monitored and evaluated the performances of their providers to ensure that these agreements represent effective uses of funds.

- People experiencing unsheltered homelessness face significant health and safety risks, increasing the importance of providing them with effective services. Both San José and San Diego have established programs to mitigate the risks that these individuals face. However, neither San José nor San Diego has measured the effectiveness of all of its programs to address the risks of unsheltered homelessness.

- Several federal and state laws and regulations may impede cities’ ability to accurately evaluate and track certain information about people experiencing homelessness. Both San José and San Diego believe that increased access to such data would allow them to better evaluate the services they provide and identify those programs that are most effective.

San José and San Diego Have Not Consistently Assessed the Effectiveness of Their Agreements With Service Providers

Both San José and San Diego spend tens of millions of dollars on efforts to reduce homelessness through agreements with external service providers, such as nonprofits. Consequently, the cities’ management of those agreements is especially crucial for establishing accountability and ensuring the effectiveness of their homelessness spending. Nonetheless, the cities’ agreements with external service providers have not always included performance benchmarks to allow the cities to assess the results of the service providers’ efforts. Moreover, our review found that the two cities did not always establish well‑defined measures for assessing the performance of their providers or ensure that the providers submitted complete performance reporting.

For each city, we reviewed 14 agreements for services such as rapid rehousing, encampment outreach, shelter, and homelessness prevention. Relying on the listings of homelessness‑related agreements the cities provided to us, we selected agreements for review based on their amounts, funding source, and program type. Eight of the 14 agreements for each city included funding from state and federal sources. The remaining six agreements primarily involved funding from local sources, including Measure E funds for San José. We evaluated each city’s agreements for defined performance measures and provider reporting requirements, and we considered each city’s assessments of provider services and its documentation of those assessments.

Well‑defined performance measures establish clear expectations for providers. For example, an effective performance measure might specify a number of people to be served per agreement activity. Nonetheless, as Table 4 shows, San José either did not establish or did not clearly define its expected performance measures in the 14 agreements we reviewed. For example, in a $12 million agreement for emergency rental assistance, San José established as a performance measure that 80 percent of program households that the provider surveyed would report improved housing stability after receiving assistance and services. However, the agreement neither specifies the number of households the provider should survey, nor did the provider disclose in its resulting report the number of households it surveyed. We believe that such specificity would provide the context for the survey’s results and help ensure that those results are an accurate representation of the services provided. The city explained that it recognizes its agreements do not include clearly defined performance measures and that it has been working with an external consultant to improve its monitoring and compliance processes.

Similarly, San Diego did not clearly define its expected performance measures in six of the 14 agreements we reviewed, as Table 5 shows. In San Diego, the housing commission managed 11 of the 14 agreements, although the city provided oversight of that management. Nonetheless, the city indicated that it did not generally require that the housing commission set specific targets or goals for the performance measures in those agreements the commission managed, unless the funding source mandated establishing such targets. For example, in a $1.6 million agreement for interim housing and supportive services, the housing commission did not specify how many people the provider should serve or set a target for shelter occupancy. Housing commission staff explained that attaching goals to certain metrics can create unintended adverse behaviors from service providers to meet those goals, which is why some previous performance metrics have moved to reporting only.

Moreover, two of San Diego’s 14 agreements did not establish any performance measures. For example, the city entered into a $415,000 agreement for outreach and engagement services but only required the service provider to report on data on referrals to services and exits to permanent housing; the city did not specify any targets or goals for the performance measures. San Diego received the report from the provider, but it was incomplete because it did not include exits to permanent housing. However, without consistently defining measurable expectations for service providers, both the city and the housing commission risk those providers’ using city dollars ineffectively and ultimately not reducing homelessness.

Aside from not consistently establishing clearly defined performance measures in the agreements they entered into, the cities also did not always ensure that they received required data on provider performance. The agreements required providers to submit reports that present data on the activities they performed and the outcomes of their efforts. For example, San José’s housing department’s agreements specify that service providers must submit quarterly performance reports through an online system that the city uses to manage grants (grants system). However, we found that the grants system was incomplete and consequently, upon our request, staff had to search elsewhere for the reporting associated with some of the agreements we reviewed. Similarly, San Diego did not receive all the necessary reporting for four of the 14 agreements we reviewed. For example, the reporting it received for one agreement for outreach services worth about $3.5 million was incomplete because it lacked a required assessment by the provider of the services in question. Without complete and clear reporting of such data, the cities’ ability to determine the effectiveness of the services they purchased is limited.

Moreover, we found that when the cities did receive provider performance data, the cities’ assessments were confusing at times. For example, in one assessment that San José performed of a $2 million amendment to an agreement for rapid rehousing services, city staff assessed a provider’s performance as “adequate.” However, the city staff’s description in the assessment of the provider’s performance indicated that the provider had failed to meet nearly all activity goals for the year. While the provider did not meet the contract performance targets, the city believes the performance was adequate given difficult circumstances related to moving people from an encampment into housing and agreed that it could have better documented why its assessment of the performance was adequate.

We identified similar problems with San Diego’s performance assessments. The housing commission explained that it uses its monthly data collection tools to compare results of a program to the contracted benchmarks and that it bases these contracted benchmarks on its CoC’s community standards and other best practice information. When we reviewed a data collection tool for an interim housing and supportive services contract, we saw that the service provider was consistently not meeting the stated benchmark of 26 percent exits to permanent housing. In fact, the percentage of exits to permanent housing was 6 percent during the term of the agreement. Given that the provider was falling significantly short of meeting this benchmark, we would have expected the housing commission to analyze the provider’s performance to determine whether the agreement was effective. However, the data collection tool did not include such an analysis from the commission.

Although both cities asserted that they monitored or reviewed the performance of their service providers, their staff did not always document overall conclusions about the effectiveness of the service providers’ efforts. One reason for this gap is that the cities’ procedures do not require staff to formally document such assessments. These types of assessments are crucial for ensuring accountability and the reduction and prevention of homelessness. San José acknowledged that its agreement management procedures are outdated, and it stated that it is in the process of updating its guidelines to include more direction on how to assess an agreement for effectiveness and how to document that assessment. According to the housing commission, the agreements in which we identified shortcomings were for new programs that had standards that changed or had not yet been developed or the nature of the agreement did not warrant certain performance metrics. The housing commission provided documentation of its efforts to ensure compliance with agreement requirements, such as reviewing samples of program files to assess areas in which providers are performing well or may require additional technical assistance. However, it agreed that it could better document its assessments of the on‑going performance of these agreements. Sometimes circumstances exist that are beyond the contractor’s control that may impact program performance, such as the COVID‑19 pandemic and housing shortages.

Without such analyses, it is unclear how the cities and the housing commission decide to renew agreements. The weaknesses we note above have limited the information available to the cities when making such decisions. For example, in fiscal year 2022–23, San José funded an agreement for homelessness prevention services with $8 million from Measure E. The service provider reported having vastly exceeded expectations on most requirements, stating that it had provided financial assistance payments to more than 1,200 households in a three‑month period when the goal was only 215. Moreover, at the end of the agreement term, the provider reported providing a total of nearly 4,000 financial assistance payments, when the goal was only 860. When we asked city staff to explain how the service provider could have achieved such results within the agreement’s budget constraints, they were initially unable to do so. However, after talking with the service provider, the city conveyed to us the service provider’s explanation that it had reported its total number of financial assistance transactions, rather than the number of unduplicated households it helped.

When we reviewed the updated version of the service provider’s results, we found that the provider actually did not meet the goal for the agreement term. In fact, it reported making only 789 payments during the agreement term. San José had not noticed or investigated the original inflated results in its assessments of the provider’s performance. Nevertheless, the city negotiated an extension to the agreement with the service provider for fiscal year 2023–24 without having accurate performance data.

Agreements with service providers are critical to cities’ efforts to reduce and prevent homelessness. When the cities either do not establish clear objectives in those agreements or do not monitor providers’ performance in achieving objectives, they risk failing to meet the needs of their residents who are experiencing homelessness.

Neither San José nor San Diego Has Measured the Effects of All Its Efforts to Mitigate the Health and Safety Risks of Unsheltered Homelessness

People experiencing unsheltered homelessness face significant health and safety risks, particularly if they live in encampments. San José has established some programs to mitigate these health and safety risks. However, it has not measured the effectiveness of those programs. San Diego has allocated resources to programs related to public health and safety and has provided services to mitigate health and safety risks for people experiencing unsheltered homelessness. Nonetheless, San Diego did not always measure the effectiveness of its programs. The cities’ lack of clear performance measures leaves them unable to assess whether their health and safety actions have effectively addressed the profound risks that individuals living in encampments face.

Because the cities have not consistently developed performance measures to evaluate the effectiveness of their programs, we reviewed the data that the cities have collected on program outcomes and on the frequency with which programs have contacted individuals experiencing unsheltered homelessness. Both cities have set some expectations related to frequency and do collect some data, however, they do not use performance measures, such as reductions in the frequency of public health‑related complaints, to evaluate effectiveness.

Although San José Took Actions to Address Health and Safety at Encampments, It Did Not Always Assess the Effectiveness of Those Actions

Beginning during the COVID‑19 pandemic, San José significantly increased its spending on programs related to the health and safety of people living in encampments and in residences in the surrounding communities. From fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23, San José budgeted a combination of federal, state, and local city funding for encampment site‑specific services and programs related to the health and safety of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness, as Table 6 shows. Its annual budgeted funding for these purposes increased from $12.7 million in fiscal year 2020–21 to $19 million in fiscal year 2022–23.

San José adopted an encampment management strategy and safe relocation policy in 2021 that generally aligns with best practices. Specifically, encampment management best practices indicate that local governments should provide access to safe places to sleep and should provide public health services.5 In addition, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness published principles for addressing encampments that specify that communities should keep encampments away from areas that are unsafe. In alignment with these principles, San José designed its policy to minimize abatements and support people experiencing unsheltered homelessness where they are unless that location presents risk factors, such as reoccurring unsanitary conditions or potential for fire.

Nonetheless, San José has not adequately evaluated its efforts to mitigate health and safety issues related to encampments. Although the city has set some expectations related to the frequency of the services it provides, it has not developed performance measures to evaluate how well its programs are mitigating health and safety risks. As a result, it is difficult to assess whether its programs are effective.

For example, San José reported that it took steps during the pandemic to mitigate public health risks at encampments by providing some encampment site‑specific services, including an enhanced weekly encampment trash program and escalated cleanups and abatements through programs such as BeautifySJ and Services, Outreach, Assistance, and Resources. Under BeautifySJ, the city committed to performing trash pickups on a weekly basis at encampments. The city’s service data indicate that it completed about 33,600 service visits at about 250 encampments from 2020 through 2023. These visits included about 22,100 regular trash service visits, about 640 biowaste cleanups, and about 590 abatements.

Although the city tracks its visits to encampments, our review of its data and reporting did not identify information demonstrating the effectiveness of its encampment services at mitigating health risks, such as a reduction in the number of public health incidents occurring at encampments. San José asserted that it was planning to hire a consultant to develop performance measures for BeautifySJ. The use of performance measures would better allow the city to evaluate whether it is achieving its goal of improving quality of life for unsheltered individuals and of creating healthy neighborhoods for all its residents.

In addition to its programs focused on mitigating health risks, San José funded two programs from fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23 that provide safety to people experiencing unsheltered homelessness: the Safe Parking program (Safe Parking) and the Overnight Warming Locations program (Warming Locations). As Table 6 describes, Safe Parking involves the city designating parking lots that have overnight security in which individuals can safely sleep in their recreational vehicles (such as motorhomes or trailers), while Warming Locations involves the city’s opening locations with security on city property for unsheltered individuals during the cold weather months.

San José’s implementation of both of these programs has addressed the safety of a small subset of the people experiencing unsheltered homelessness. For example, San José reported providing Safe Parking at two city‑owned sites for people who sleep in their recreational vehicles. It stated that the program temporarily served about 162 individuals during fiscal year 2020–21. However, city staff explained that the city did not renew the agreement with this service provider after it expired in June 2021 because the city had changed how it wished to serve people residing in vehicles. The city did not open a new safe parking location until recently, in July 2023. This new location currently can serve about 42 recreational vehicles on a daily basis, which is far fewer than the 700 recreational vehicles in which the city estimates people are living.

In addition, in June 2022, San José approved funding for a Safe Parking program for people who sleep in their cars. However, according to city staff, it did not open this location because a site for safe parking could not be identified by the city. Without a sufficient number of safe parking sites, the city increases the safety risks, such as physical or emotional threats, that people who sleep in their vehicles may face.

Moreover, the city was unable to follow through with its plans to abate one of two large encampments by its airport. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) mandated that for safety reasons, San José must abate an encampment at Guadalupe Gardens because the park is in the airport’s flight path. In October 2022, San José reported to the FAA that it successfully had done so. The city also planned to abate an encampment at Columbus Park, which is adjacent to Guadalupe Gardens, by November 2022. However, it now does not expect to complete this abatement until the end of 2024 at the earliest. The city indicated that not everyone in the encampment was able to relocate to Safe Parking sites because some did not qualify for the program for reasons including not being able to provide proof of vehicle ownership. Accordingly, the city indicated that Columbus Park has continued to serve as an encampment for more than a dozen vehicles.

Although city staff stated that San José Police Department officers accompany the BeautifySJ team during abatements on an on‑demand basis, the city does not have specialized police units dedicated to the concerns of individuals experiencing unsheltered homelessness. In 2018 the San José Police Department received a grant to start a new program—the Mobile Crises Assessment Team—that sends a team of dedicated officers and county behavioral health clinicians to respond immediately to community members experiencing mental health crises. The police department asserted that this program is intended to serve both people who are experiencing unsheltered homelessness and those who are living in residences. However, police department staff explained that the program primarily serves people in residences. In contrast, San Diego has police units dedicated to working with and providing outreach to people experiencing unsheltered homelessness, as we discuss in the section that follows.

San José also has not established a consistent and formalized process for working with the county health department at encampments. In its fiscal year 2020–21 annual report to a city council committee, the city described its joint efforts with the county health department during the COVID‑19 pandemic, which included providing vaccines to people experiencing unsheltered homelessness. However, the city staff indicated that the city does not have a contract with the county health department to establish each party’s roles and responsibilities for mitigating public health risks.

According to the city staff, San José relies primarily on its outreach contractors to report to the county public health‑related risks at encampments. In addition, the city explained that it collaborates with the county to address health concerns such as outbreaks. However, San José’s lack of an established process for working with the county’s health department to identify and mitigate public health risks at encampments could cause delays in the city’s response to public health emergencies in the future. The city agreed that it could strengthen or formalize its collaboration with the county on significant public health concerns.

Although San Diego Has Taken Actions to Address Health and Safety at Encampments, It Does Not Measure the Effectiveness of All Its Programs

San Diego’s total budgeted funding for public health and safety related to unsheltered homelessness has increased over the last three fiscal years, as Table 7 shows. From fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23, San Diego increased its budgeted funding for programs that help ensure the health and safety of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness and living in residences in the communities surrounding encampments. Over this period, the city’s total budgeted funding for these programs grew from $32 million to $43 million.

However, San Diego has not evaluated the effectiveness of some of its health and safety programs, limiting its ability to determine whether these programs have helped to mitigate the risks for people experiencing unsheltered homelessness. For example, the Neighborhood Policing Division (NPD) in the San Diego Police Department provides homelessness outreach and proactive enforcement services for the safety of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness and residents in the surrounding community, as Table 7 shows. City staff explained that NPD collects general data on a daily basis, including the number of people its Homeless Outreach Team reached, assisted, or placed into housing. NPD staff provided data from 2020 through 2022 that indicate that the NPD Homeless Outreach Team officers reached about 18,000 to 23,000 people per year and placed about 850 to 2,300 people per year into a shelter. However, city staff indicated that these data are not unduplicated and that NPD does not have measures to evaluate the effectiveness of its actions and has identified other potential measures such as the number of individuals directed to mental health services and response times to complaints from residents.

Although the city collects data about program actions, San Diego also has not measured the effectiveness of some of its programs that focus on health. For example, as part of its Clean SD program, San Diego identified actions— such as sanitizing sidewalks and addressing illegal dumping—that mitigate health risks to the public, including people experiencing unsheltered homelessness. For example, Clean SD has crews that clean up waste and litter on a daily basis from areas near encampments that pose a public health or environmental concern. Clean SD staff provided data that indicate that from fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23, the program annually abated from 1,200 to 2,300 encampments, sanitized sidewalks by cleaning about 6,600 to 8,500 blocks to reduce the potential presence of bacteria and communicable diseases, and addressed from 5,000 to 7,000 encampment‑related complaints from the public.

Although the city tracked these data and set some expectations around the frequency with which Clean SD would provide services, it did not develop performance measures for evaluating the program’s effectiveness, such as a reduction in public health incidents arising from encampments. City staff explained that the city did not develop such measures because Clean SD has always been a collaboration among different city departments and lacked a central manager. According to the city staff, the city did not make Clean SD into a separate division within its Environmental Services Department until fiscal year 2023–24. City staff explained that the city is working with the new division’s management to develop performance measures that it can use to evaluate the program’s impact.

San Diego has measured the number of people served by some city‑funded programs designed to ensure the health and safety of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness. For example, from fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23, the city and the housing commission administered programs through agreements with service providers to meet the immediate health and safety needs of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness, including programs that provided safe parking and safe sleeping. The city reported that it has four safe parking locations for recreational vehicles and cars with a total of 233 parking spots, and its website indicates that it has two safe sleeping locations that can serve 533 tents. The city reported that its safe parking program served more than 3,000 people in fiscal years 2020–21 through 2022–23, as Table 7 shows. In addition to the sites it already has, San Diego has identified options for more safe parking and safe sleeping locations to ensure individuals’ safety while the city searches for other shelter options.

As the result of a previous public health incident, San Diego has established formal collaboration with the county for its work on public health. Specifically, the city entered into a memorandum of agreement (MOA) with San Diego County’s Health and Human Services Agency (HHSA) in 2020 to clarify their contractual relationship related to public and environmental health services. The city and county took this action following a 2018 San Diego County grand jury report that revealed that they did not coordinate their responses during a hepatitis A outbreak in the city among individuals who were experiencing unsheltered homelessness that resulted in 20 deaths.6 The California State Auditor’s 2018 audit report included similar findings.7

The current, collaborative process facilitates the city and the county working together to identify public health risks at encampments and address them in a timely manner. The public health and safety MOA clarifies the city’s and county’s roles and responsibilities in their coordinated response to public health matters. In October 2021, San Diego County’s HHSA reported an outbreak of shigellosis—an intestinal infection—among people experiencing homelessness in the city. In January 2022, the city declared the outbreak resolved without any deaths. It credited this outcome to its work with the county, demonstrating the importance of having a coordinated response.

The Cities’ Limited Access to HMIS Data May Impede Their Efforts to Evaluate Homelessness Programs

Several federal and state laws and regulations may impede the ability of the State and local jurisdictions to accurately assess and track certain information about people who are experiencing homelessness. The text box lists some of these laws, which generally protect the confidentiality of personal information. The limitations to data‑sharing further emphasize the importance of the cities’ monitoring the performance of their service providers to ensure the success of the programs they fund.

Federal and State Laws and Regulations Limit the Data That Can Be Shared Without Consent

FEDERAL

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act: Applies to health plans and certain health care providers. Some protected health information data may be disclosed without consent if the data will only be used for limited purposes.

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act: Applies to educational agencies or institutions that receive federal funding. Personally identifiable information from educational records can be disclosed without consent as long as it is used for purposes related to that person’s education.

Violence Against Women Act: Applies to covered housing providers who serve victims of domestic or dating violence, sexual assault, or stalking. The providers cannot share a victim’s information without consent of the victim.

HMIS Standards: Client consent is required to share data but not to enter data into HMIS.

Substance Use Records: Some records can be disclosed without consent in case of medical emergency, research, or audit purposes. Consent form must outline exactly what can be disclosed; can be revoked at any time.

STATE

Confidentiality of Medical Information Act: Individual must consent to disclosure of medical information by a health care plan or provider unless there is a court order, search warrant, death investigation, or need for diagnosis or treatment.

Information Privacy Act of 1977: Individual must consent to disclosure of personal information by a state agency unless there is a legal requirement or a medical necessity.

Juvenile Case Records: Files may only be accessed by someone who is related to, works with, or represents the child.

Source: Federal and state laws.

The main source of data about people experiencing homelessness is HMIS, for which the CoCs are responsible. HMIS is a local information technology system in which recipients and subrecipients of federal funding record and analyze client, service, and housing data for individuals and families at risk of or experiencing homelessness. CoCs must ensure compliance with the federal Privacy and Security Standards for HMIS. These standards allow certain uses of a person’s protected personal information (protected information), including for service provision and coordination, service payment and reimbursement, administrative functions such as audits, and removing duplicate data. Although the standards allow local governments to access data they enter into HMIS, they may not have access to personal information entered by other entities. CoCs use consent forms to allow them to use data provided by people who access homelessness services.

Both cities we reviewed indicated that they believe they would benefit from greater access to HMIS data. San José has an agreement with Santa Clara County to have full access to data that the city has entered into the county’s HMIS. Through this agreement, San José is required to participate in HMIS and must comply with HUD data standards when collecting data. The agreement also requires the city to comply with federal and state confidentiality laws and regulations.

San José’s deputy city manager for homelessness indicated that if the city fully utilized data available in HMIS, it would be able to understand and analyze the data better and make better decisions about its programs for preventing and ending homelessness, and that the city is working with the county to expand its access to HMIS to the City Manager’s Office, as well as other departments whose staff work directly with people experiencing homelessness. He further stated that having access to disaggregated data could enable the city to understand changes in the demographics of the population experiencing homelessness and adjust its approach to better suit their needs. He also stated that the city could track which programs are working and understand additional questions or areas to explore to understand why they are working.