2023-046 Proposition 56 Tobacco Tax

The California Department of Public Health Should Improve Its Monitoring of One of Its Tobacco-Related Programs

Published: November 13, 2024Report Number: 2023-046

November 13, 2024

2023-046

The Governor of California

President pro Tempore of the Senate

Speaker of the Assembly

State Capitol

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As required by Revenue and Taxation Code section 30130.56, my office conducted an audit of the use of Proposition 56 tobacco tax revenue, and this report details the audit’s findings and conclusions. In general, we determined that the California Department of Public Health (Public Health) is not sufficiently monitoring one of its three Proposition 56 funded programs. Additionally, two entities—Public Health and University of California (UC)—reported inaccurate revenue information for specific Proposition 56 funded programs.

Although Public Health did ensure that its Oral Health Program (OHP) awarded funding to activities in alignment with Proposition 56’s requirements to support the state dental plan, the program did not adequately monitor its contractors’ progress toward completing agreed-upon work. For example, although progress reports are one way for contractors to demonstrate to the OHP whether they have completed agreed-upon work, the OHP could not demonstrate that its staff had reviewed all progress reports for seven of the 20 agreements that we reviewed for this program. In addition, the OHP paid one contractor approximately $140,000 despite not having received all of its progress reports and accepting other progress reports from the contractor that were incomplete. In contrast, Public Health did appropriately oversee the other two Proposition 56 funded programs it administers.

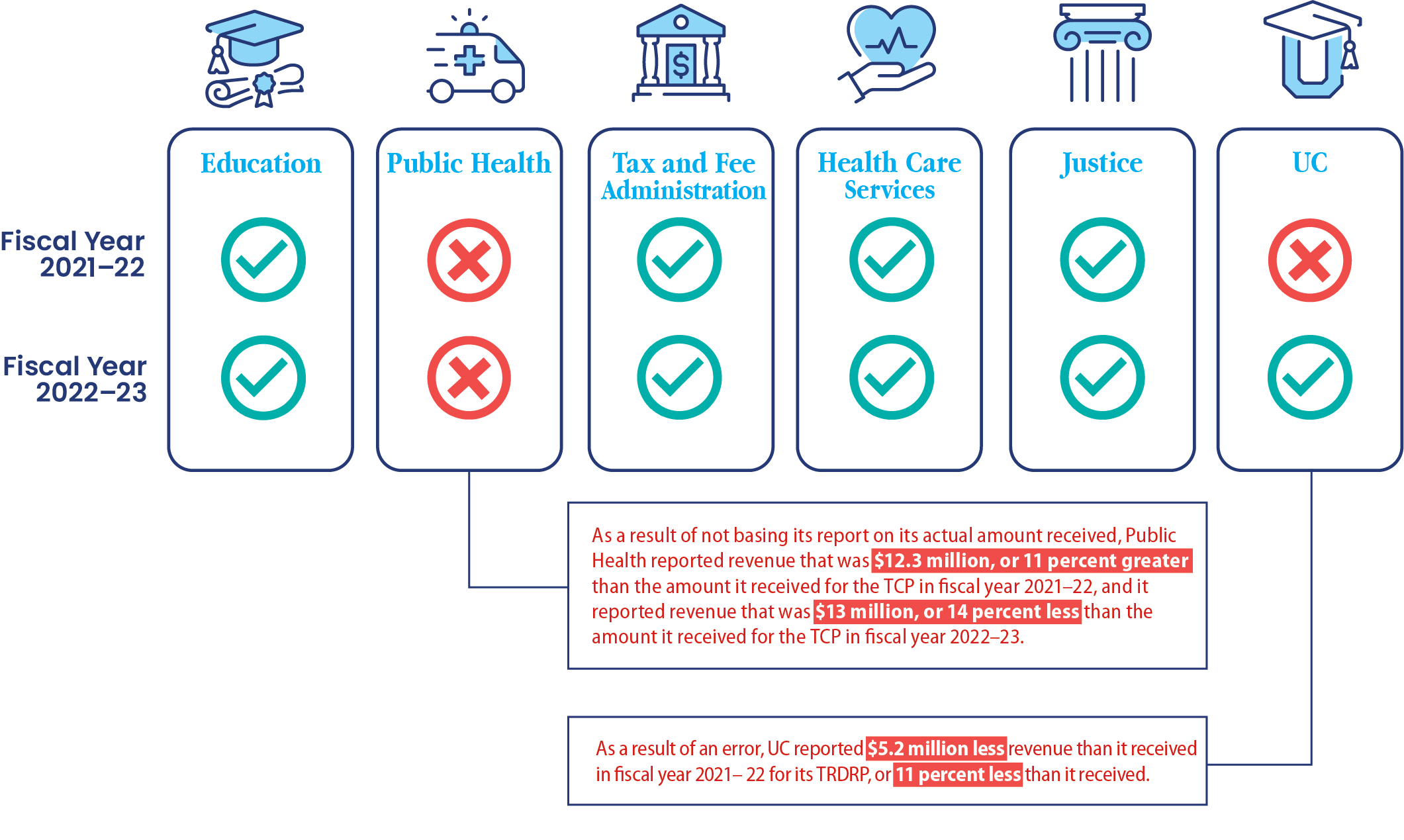

As state law requires, all six entities that we reviewed reported on their websites the amount of Proposition 56 tax revenue that they received and how they spent it in fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23. However, because of a one-time error, UC reported $5.2 million less than the revenue that it received for one of its programs, or 11 percent of its total revenue, in fiscal year 2021–22. Public Health reported revenue for its Tobacco Control Program that was $12.3 million, or 11 percent greater than the amount it received in fiscal year 2021–22, and it reported revenue that was $13 million, or 14 percent less than the amount it received in fiscal year 2022–23 because it used year-end estimates instead of actual amounts received. Nevertheless, all six entities adhered to Proposition 56’s requirement that limits them from spending more than 5 percent of their allocations on administrative costs.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

| OHP | Oral Health Program |

| STAKE | Stop Tobacco Access to Kids Enforcement |

| TCP | Tobacco Control Program |

| TRDRP | Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program |

| UC | University of California |

Summary

Key Findings and Recommendations

In 2016 California voters approved Proposition 56, which enacted the California Healthcare, Research and Prevention Tobacco Tax Act of 2016. Proposition 56 added $2 in taxes per pack of 20 cigarettes beginning in 2017, and it imposed an equivalent tax increase on other tobacco products, such as cigars, chewing tobacco, and e-cigarettes containing nicotine.

Proposition 56 imposes these taxes with the intent of saving the lives of Californians by reducing smoking and tobacco use, which result in 40,000 deaths per year in the State according to a 2023 California Department of Public Health (Public Health) report. Proposition 56 funds programs that, among other things, reduce tobacco use, treat tobacco-related diseases, and enable health-related research, and it prohibits entities receiving these funds from using more than 5 percent of their allocations on their administrative costs.

Proposition 56 tobacco tax revenue funds programs administered by the California Department of Education (Education), the Department of Health Care Services (Health Care Services), the California Department of Justice (Justice), Public Health, the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration (Tax and Fee Administration), and the University of California (UC). This tax revenue also provides funding to offset the reduction in certain state and local government funds due to decreases in tobacco consumption that Tax and Fee Administration determines directly resulted from the additional taxes that Proposition 56 imposes. Finally, in an effort to provide public accountability, Proposition 56 requires the entities its revenue supports to annually account for their use of the funds by posting reports on their websites. These reports must specify how much tax revenue each entity received and how that money was spent.

Public Health Is Not Sufficiently Monitoring One of Its Proposition 56 Funded Programs

Public Health administers three Proposition 56 funded programs: the Tobacco Control Program (TCP), Stop Tobacco Access to Kids Enforcement (STAKE), and the Oral Health Program (OHP). The department has established policies for the TCP for awarding and monitoring the use of Proposition 56 funds to help ensure that the program uses funds in accordance with state law.1 We found that Public Health ensured that the TCP funding it awarded was spent in alignment with Proposition 56’s requirements to support tobacco‑related health communication activities. Further, Public Health demonstrated that the TCP monitored its contractors’ progress toward completing agreed-upon work. Additionally, Public Health properly allocated STAKE Proposition 56 funds toward activities that support the enforcement of laws related to illegal sales of tobacco to underage purchasers. Moreover, Public Health ensured that its OHP awarded funding to activities in alignment with Proposition 56’s requirements to support the state dental plan based on demonstrated oral health needs and that prioritize serving underserved areas and populations. However, Public Health did not ensure that the OHP adequately monitored its contractors’ progress toward completing agreed-upon work. For example, although progress reports are a way for contractors to demonstrate to the OHP that they have completed agreed-upon work, the OHP could not demonstrate that its staff had reviewed all contractor progress reports for seven of the 20 agreements that we reviewed for this program. The OHP also paid one contractor approximately $140,000 despite not having received all of its progress reports and accepting other progress reports from the contractor that were incomplete. Without documented and specific policies to monitor whether its contractors use Proposition 56 funding in accordance with their agreements, the OHP increases its risk that its contractors will use Proposition 56 funding in a manner that does not support the goals of the state dental plan to improve oral health and achieve oral health equity for all Californians.

Two Entities Reported Inaccurate Revenue Amounts, but All Six Entities Complied With Administrative Cost Spending Limits

As state law requires, all six entities we reviewed reported on their websites the amount of Proposition 56 tax revenue that they received in fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23 and how it was spent. However, two entities—Public Health and UC—reported inaccurate revenue information for specific Proposition 56 funded programs. UC reported $5.2 million less revenue than it received in fiscal year 2021–22 for its Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP), or 11 percent less than it received. Public Health reported revenue that was $12.3 million, or 11 percent greater than the amount it received for the TCP in fiscal year 2021–22, and it reported revenue that was $13 million, or 14 percent less than the amount it received for the TCP in fiscal year 2022–23. Nevertheless, the six entities adhered to Proposition 56’s requirement that limits them from spending more than 5 percent of their allocations on administrative costs.

To address these findings, we recommend that Public Health develop policies for the OHP that require its staff to confirm the completion of agreed-upon work before approving payment of contractor invoices. We also recommend that Public Health and UC report on their respective websites the amount of Proposition 56 revenue that they actually received beginning with their fiscal year 2023–24 revenue.

Agency Comments

Public Health and UC indicated they would take action to implement our recommendations. Because we did not make recommendations to Education, Health Care Services, Justice, and Tax and Fee Administration, we did not request them to respond.

Introduction

Background

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, cigarette smoking remains the leading cause of preventable death and disability in the U.S., despite the significant decline in the number of people who smoke. In California, smoking‑related illnesses together result in 40,000 deaths per year, according to a report published by the California Department of Public Health (Public Health) in 2023. In 2016 California voters approved Proposition 56, which enacted the California Healthcare, Research and Prevention Tobacco Tax Act of 2016.

Proposition 56 imposed a tax on tobacco products beginning in 2017, with the intent of saving the lives of Californians by reducing tobacco use and increasing funding for tobacco-use prevention programs, health-related research, and existing health care programs and services that treat tobacco-related and other diseases. Proposition 56 added $2 in taxes per pack of 20 cigarettes and imposed an equivalent tax increase on other tobacco products, such as cigars, chewing tobacco, and e‑cigarettes containing nicotine.

The California Department of Tax and Fee Administration (Tax and Fee Administration) reported that the number of packs of cigarettes distributed and taxed in the State has decreased in the past six fiscal years from 651 million to 465 million and, as Proposition 56 foresaw, when cigarette sales decrease, so too does the tobacco tax revenue available for relevant programs.

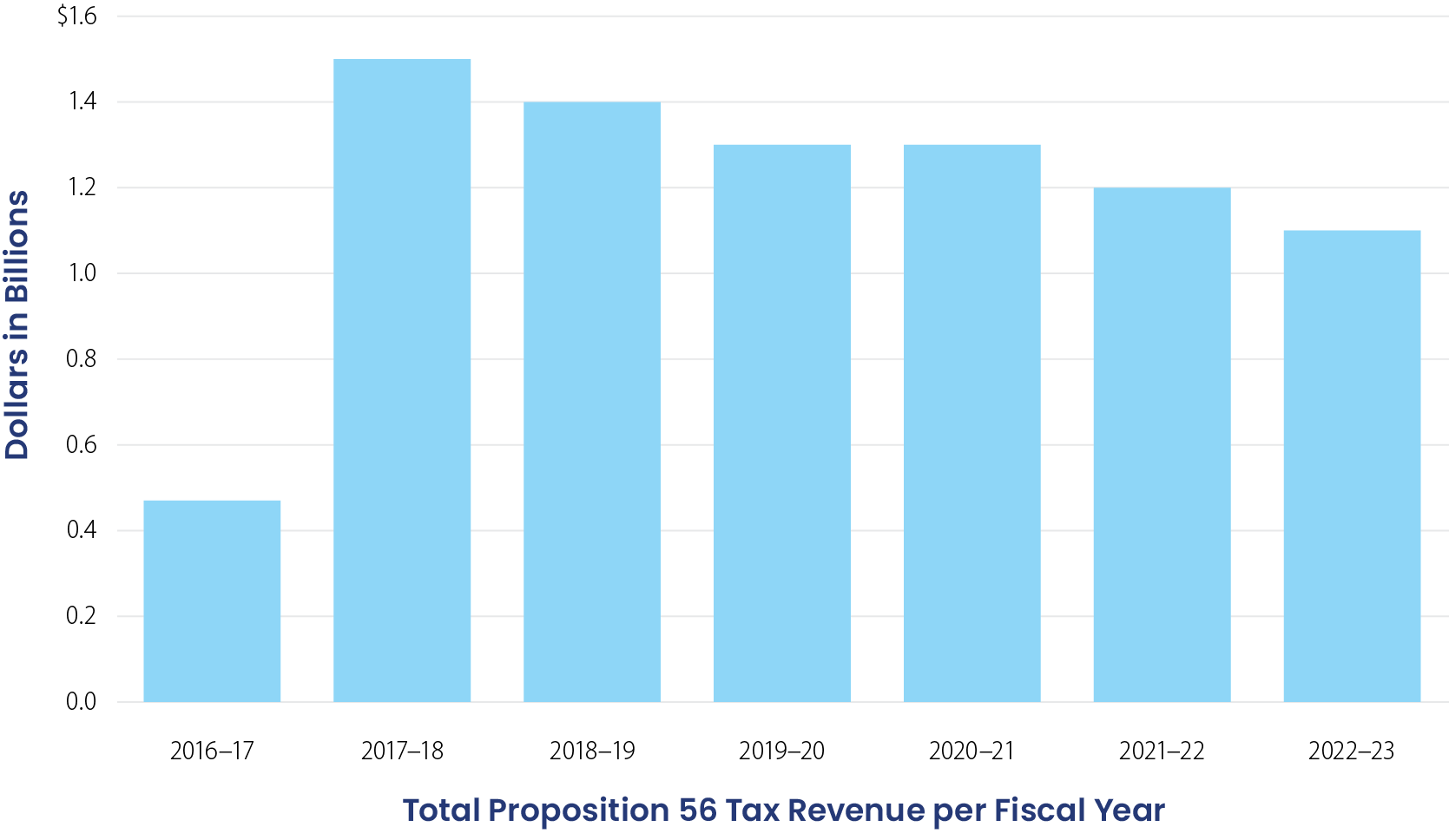

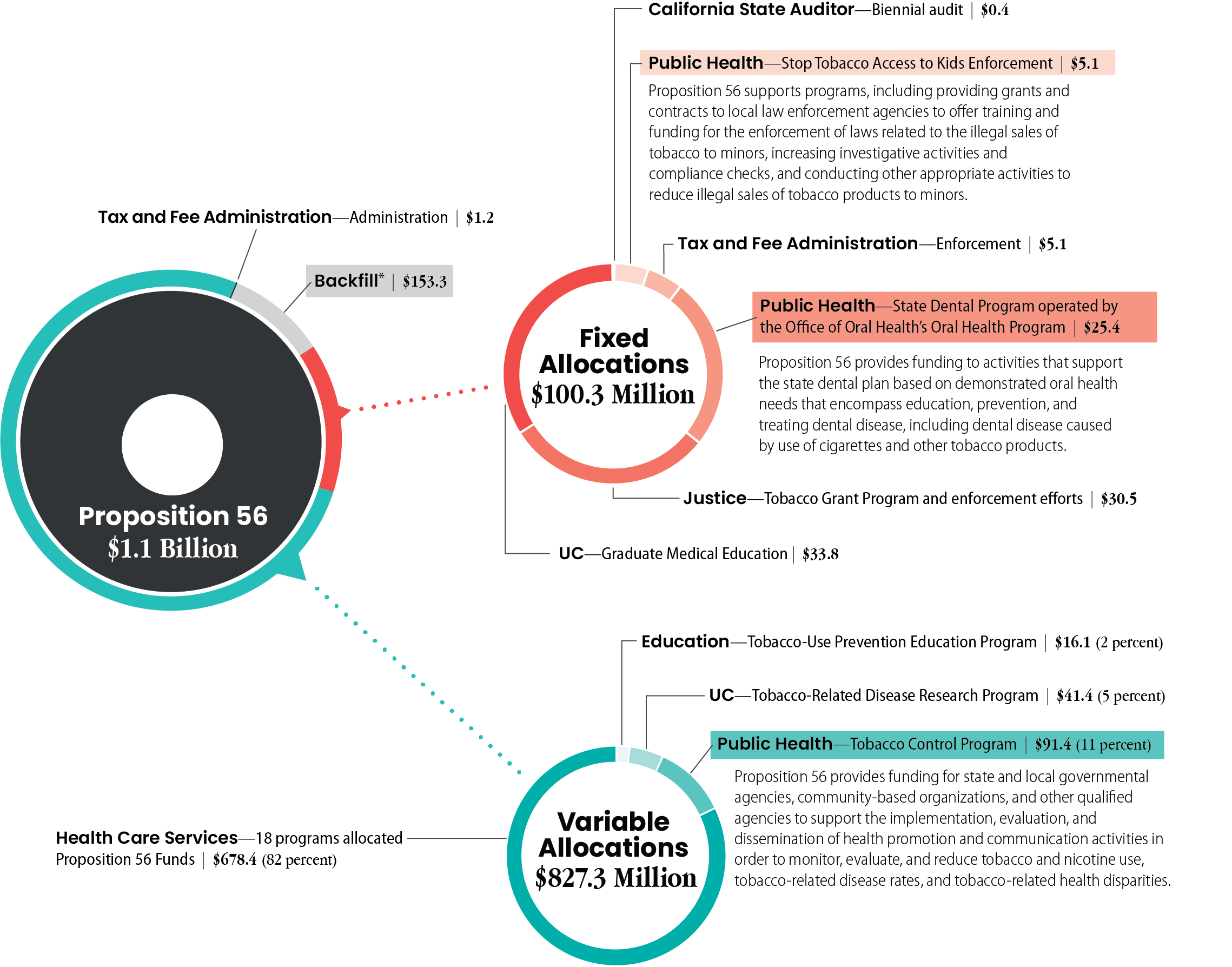

Tax and Fee Administration is responsible for collecting Proposition 56 tax revenue, which it deposits into the California Healthcare, Research and Prevention Tobacco Tax Act of 2016 Fund (tobacco tax fund). As Figure 1 shows, the annual amount of Proposition 56 tax revenue that Tax and Fee Administration reported collecting has steadily decreased since fiscal year 2017–18. Tax and Fee Administration also annually determines the extent to which Proposition 56 has resulted in a decrease in tobacco tax revenue for select other funds. The State Controller’s Office (State Controller) then transfers funds from the tobacco tax fund to the select funds in the amount necessary to offset the determined decreases in revenue to those funds. We describe the portion of Proposition 56 funding that the State Controller transfers to offset the decreased revenue—more than $153 million in fiscal year 2022–23—as the backfill. Figure 2 shows how the law allocated the $1.1 billion in Proposition 56 tobacco tax revenue that Tax and Fee Administration collected in fiscal year 2022–23.

Figure 1

Proposition 56 Tax Revenue Has Declined Since Fiscal Year 2017–18

Figure 1 shows the annual amount of Proposition 56’s tax revenue that Tax and Fee Administration collected starting in fiscal year 2016-17 through 2022-23. The tax revenue in fiscal year 2016-17 was about $500 million. The tax revenue in fiscal year 2017-18 was about $1.5 billion. The tax revenue in fiscal year 2018-19 was about $1.4 billion. The tax revenue in fiscal years 2019-20 and 2020-21 was about $1.3 billion. The tax revenue in fiscal year 2021-22 was about $1.2 billion. The tax revenue in fiscal year 2022-23 was about $1.1 billion. Note: The Tax and Fee Administration began collecting Proposition 56 tax revenue in April 2017, the fourth quarter of the fiscal year 2016-17.

Source: Tax and Fee Administration’s Open Data Portal and year-end financial statements.

Note: Tax and Fee Administration began collecting Proposition 56 tax revenue in April 2017, the fourth quarter of fiscal year 2016–17.

Figure 2

California Collected and Allocated $1.1 Billion in Proposition 56 Tobacco Tax Revenue During Fiscal Year 2022–23 (Dollars in Millions Unless Otherwise Specified)

Figure 2 shows how Tax and Fee Administration allocated the $1.1 billion in Proposition 56 tax revenue that it collected in fiscal year 2022-23. Tax and Fee Administration allocated $1.2 million to itself for its administration, calculation, and collection of Proposition 56 tax revenue. The State Controller allocated $153.3 million to the backfill, which is the amount transferred to other tobacco tax funds and state and local governments to replace certain tax revenues lost as a result of any decrease in tobacco sales that Tax and Fee Administration determines was caused by price increases associated with Proposition 56. The State Controller allocated $100.3 million to programs and activities with specific allocation amounts determined in Proposition 56, which we group as fixed allocations. Of the fixed allocations, the State Controller allocated $33.8 million to UC for its Graduate Medical Education program, $30.5 million to Department of Justice for its Tobacco Grants Program and enforcement activities, $25.4 million to Public Health for its OHP, $5.1 million to Tax and Fee Administration for enforcement activities, $5.1 million to Public Health for its STAKE program, and 400,000 to the California State Auditor to conduct biennial independent financial audits of the state and local agencies receiving Proposition 56 tax revenue. Finally, the State Controller allocated $827.3 million to programs and activities with allocation amounts that are specific percentages of remaining funds determined in Proposition 56, which we group as variable allocations. Of the variable allocations, Tax and Fee Administration allocated $678.4 million to Health Care Services for 18 programs that it funds with Proposition 56 tax revenue, $91.4 million to Public Health for its TCP, $41.4 million to UC for its Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program, and $16.1 million to Department of Education for its Tobacco-Use Prevention Education Program. Figure 2 also includes descriptions of the intended uses of Proposition 56 funding for Public Health’s STAKE, OHP, and TCP programs–the programs selected for review in this audit–as follows. For STAKE, Proposition 56 supports programs, including grants and contracts to local law enforcement agencies to offer training and funding for the enforcement of laws related to the illegal sales of tobacco to minors, increasing investigative activities and compliance checks, and conducting other appropriate activities to reduce illegal sales of tobacco products to minors. For OHP, Proposition 56 provides funding to activities that support the state dental plan based on demonstrated oral health needs that encompass education, prevention, and treating dental disease, including dental disease caused by use of cigarettes and other tobacco products. For TCP, Proposition 56 provides funding for state and local governmental agencies, community-based organizations, and other qualified agencies to support the implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of health promotion and communication activities in order to monitor, evaluate, and reduce tobacco and nicotine use, tobacco-related disease rates, and tobacco-related health disparities.

Source: State Controller’s financial system; Tax and Fee Administration’s Open Data Portal, budgetary information, and internal memo; interviews with Tax and Fee Administration staff; and state law.

Note: Certain programs receive an allocation of a specific amount determined in Proposition 56, which we have grouped as Fixed Allocations, and other programs receive an allocation that is a specific percentage of remaining funds, which we have grouped as Variable Allocations. Also, the highlighted programs represent those selected for review in this audit.

* The backfill is the amount Tax and Fee Administration distributes to other tobacco tax funds and state and local governments to replace certain tax revenues lost as a result of any decrease in tobacco sales caused by price increases associated with Proposition 56.

Proposition 56 Audit Requirements

Proposition 56 requires that the California State Auditor biennially conduct an independent audit of the entities that receive Proposition 56 tobacco tax revenue as the text box identifies. State law allows entities to spend no more than 5 percent of their Proposition 56 allocations on administrative costs, which generally include expenditures for the support of state government such as equipment replacement, repair projects, and lease or rental costs, and it requires the State Auditor to conduct a biennial audit to review those costs. State law allows the State Auditor to determine whether to include certain additional elements in the audit. Because Proposition 56 requires entities that receive its tax revenue to report annually on their websites an accounting of the amounts that they receive and how they spent the funds, we also evaluated the accuracy of those reports.

Entities Included in the State Auditor’s Biennial Audit

- California Department of Education

- California Department of Justice

- California Department of Public Health

- California Department of Tax and Fee Administration

- Department of Health Care Services

- University of California

Source: State law.

In addition to auditing the entities’ compliance with reporting requirements and their adherence to administrative cost limits, we chose to review whether the processes by which the three programs that Public Health funds with its allocation of the tax revenue ensure the appropriate use of that funding. We reviewed the Tobacco Control Program (TCP), the Oral Health Program (OHP), and Stop Tobacco Access to Kids Enforcement (STAKE), all of which we highlight and describe in Figure 2. These three programs collectively represent the second largest allocation of Proposition 56 funding to a single entity after the largest allocation provided to the Department of Health Care Services (Health Care Services), whose programs we reviewed in a previous biennial Proposition 56 audit report.2 For these three Public Health programs, we assessed whether the programs’ practices and Public Health’s oversight ensured that the programs used their Proposition 56 tax revenue allocation to meet the programs’ legal requirements. To achieve their purposes, the programs either perform work using their own staff, contract with contractors, or make grants to other entities, such as community-based organizations for the TCP and local health jurisdictions for the OHP. In this report, we reference all of the documented contract or agreement terms that define agreed-upon work and outcomes from contractors or grant recipients as agreements.

Issues

Public Health Is Not Sufficiently Monitoring One of Its Proposition 56 Funded Programs

Public Health Is Not Sufficiently Monitoring One of Its Proposition 56 Funded Programs

Key Points

- Public Health awarded Proposition 56 funding to contractors for the TCP in alignment with Proposition 56’s requirements, and TCP staff monitored those contractors to ensure that they completed tobacco-related health promotion and communication activities.

- Public Health awarded Proposition 56 funding to contractors for the OHP in alignment with Proposition 56 requirements to support the state dental plan. However, OHP staff did not sufficiently monitor those contractors to ensure that they completed their agreed‑upon work, likely because the OHP lacked policies to guide its monitoring efforts.

- Public Health allocated STAKE’s Proposition 56 funding toward activities that complied with state law supporting the enforcement of laws related to illegal sales of tobacco to the underage population.

The TCP Appropriately Monitored Contractors’ Compliance With the Terms of Their Agreements

Proposition 56 provides Public Health with funding for the TCP and directs it to award funding to qualified entities, such as state and local governmental agencies, tribes, and universities, for health communication activities to reduce tobacco use, among other activities. The TCP was established as a result of California voters approving of Proposition 99 in November 1988, nearly 30 years before voters approved Proposition 56. Proposition 99 imposed an additional one and one-quarter cent tax for each cigarette distributed and required that a portion of these funds be appropriated for programs for the prevention and reduction of tobacco use through education programs. In addition to funding that it continues to receive from Proposition 99 revenue, the TCP receives the largest share of Public Health’s Proposition 56 allocation—$91.4 million in fiscal year 2022–23, as Figure 2 shows. The TCP uses its Proposition 56 allocation for activities such as providing grant funding to local health centers to improve their tobacco-cessation efforts, contracting for reviews and updates of tobacco-related education materials, and contracting for a public awareness media campaign that aims to reduce the morbidity and mortality caused by tobacco use. The law also requires the TCP to use at least 15 percent of the funds it distributes to accelerate and monitor the decline in tobacco-related disparities with the goal of eliminating those disparities.3

Public Health has established formal policies and procedures to help ensure that the TCP uses its Proposition 56 funding as the law requires. To draw this conclusion, we evaluated whether the TCP had in place policies and procedures that address best practices in contract management identified by the U.S. Government Accountability Office and requirements for awarding and monitoring agreements established in the State Contracting Manual. Such policies would ensure that the TCP uses funding for purposes that align with Proposition 56’s requirements and that it awards contracts to eligible entities. We found that the TCP does have policies and procedures that address best practices and requirements, which include screening potential awardees to ensure that they are eligible to receive Proposition 56 funding, reviewing the applicants’ ability to complete the necessary work and their proposed budgets for completing the work, and reviewing contractors’ progress reports to monitor progress on the scope of work outlined in the agreement. Additionally, TCP policies require its staff to review the contractors’ invoices and compare them to the budget and scope of work outlined in its agreements before the program authorizes payments.

Further, we evaluated whether the TCP complied with its policies and procedures for awarding agreements to ensure that its use of Proposition 56 funding complied with the law’s requirements. We reviewed a judgmental selection of 20 of TCP’s Proposition 56 funded agreements—representing about 12 percent of the 165 agreements that the TCP issued—that it initiated in fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23. We conducted this review to determine whether the program complied with its policies when awarding the agreements. We found that Public Health awarded funds for uses in alignment with Proposition 56 requirements for all 20 agreements. For example, Public Health appropriately awarded an agreement with a maximum value of $200 million over a five‑year period to a contractor to conduct a statewide public awareness media campaign in support of efforts to reduce the morbidity and mortality caused by tobacco use. Further, Public Health allocated a portion of these funds toward eliminating tobacco‑related disparities by targeting certain population segments—such as African American and Asian communities—in order to increase support for tobacco-free social norms.

We also evaluated whether the TCP complied with its policies and procedures for monitoring agreements to ensure that its contractors used their funding as agreed. For example, Public Health has a policy requiring its staff to confirm timely and accurate receipt of goods and services and progress reports from contractors. TCP policies identify progress reports as a primary communication tool between the TCP staff and contractors, and as a mechanism for understanding how contractors used TCP’s Proposition 56 funding. These reports include information such as the contractor’s progress on agreed-upon work and descriptions of unexpected challenges the contractor may have experienced in completing this work. In our review of the 20 TCP agreements, we found that TCP staff ensured that each contractor submitted its required progress reports in fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23 and that TCP staff reviewed each report to assess the contractor’s progress, as the program’s policy required.

Public Health also has a policy specifying how its staff should evaluate progress reports to determine whether the reports sufficiently address the contractor’s efforts to meet the program’s goals. TCP policy requires staff to review progress reports for completeness and timeliness, and it requires staff to provide feedback to contractors when their performance does not meet the TCP’s expectations. For example, when reviewing progress reports from one contractor, a TCP staff reviewer noted that the contractor had not made sufficient progress toward an objective related to maintaining a youth group that would work on tobacco-related policy changes and that the contractor would therefore need to accelerate its progress to stay on schedule.

In addition to providing updates to the TCP on their progress, contractors are required to submit supporting documents, such as agendas from meetings with workgroups regarding activities to promote tobacco cessation, presentations used to educate youth on tobacco-related policies, or a draft of an evaluation and analysis plan to examine Proposition 56’s impact on addressing tobacco-related health disparities. The program uses such documents to verify the information in the progress reports. In the progress reports that we reviewed, we found evidence that the contractors did not always include the documentation that TCP staff expected. Nonetheless, TCP staff appropriately provided feedback to the contractors that they should submit the missing documentation in the next progress report. For example, TCP staff noted that one contractor included incorrect tracking measures for one of its activities and directed the contractor to include the correct tracking measures in the following progress report.

The policy also includes steps for staff to take when contractors do not meet contractual requirements, such as by withholding payment to contractors who do not submit timely and accurate agreement deliverables. TCP policy prescribes progressive levels of corrective action to address deficient performance. For example, if the TCP rejects a progress report that it receives from a contractor, its procedures require the program consultant to contact the contractor to obtain clarification on progress issues and to identify corrective actions. The program can also direct its in-house auditor to review the fiscal and supporting documentation from the contractor, which TCP staff asserted could help the program identify necessary corrective actions to take with the contractor. Ultimately, the program may terminate its agreement with the contractor if it rejects three or more progress reports, and the contractor does not take the necessary corrective actions. In our review of TCP’s efforts to analyze progress reports, we saw evidence that TCP staff members had appropriately contacted contractors to identify corrective actions, although we did not identify any instances that would have required the TCP to implement additional corrective actions beyond this first step.

The OHP Lacked Key Controls to Ensure That Its Contractors Appropriately Used Proposition 56 Funding

Although the OHP awarded Proposition 56 funding for appropriate uses, its staff did not sufficiently monitor its contractors’ use of those funds, likely because Public Health lacks a formal policy to guide OHP staff in performing such monitoring, which thereby increases the risk that OHP’s contractors may misuse that funding. Of Public Health’s three programs that receive Proposition 56 funding, the OHP receives the second largest allocation, $25.4 million, as Figure 2 shows. Proposition 56 provides the OHP with funding for activities that support the state dental plan based on demonstrated oral health needs and that prioritize serving underserved areas and populations. These activities include education, disease prevention, disease treatment, surveillance, and case management.

The OHP awards most of its Proposition 56 funds through agreements with local health jurisdictions, such as county health departments, enabling them to operate local oral health programs. The OHP also awards a portion of its funding through agreements with other contractors, such as universities, for oral health-related projects. We reviewed a judgmental selection of 20 OHP agreements—representing 15 percent of the 136 agreements that we identified—that the OHP funded using Proposition 56 funding during fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23. We found that the OHP awarded funds through these agreements for uses that align with Proposition 56 requirements. Specifically, the OHP ensured that the scope of work in its agreements we reviewed addressed activities related to oral health education, disease prevention, and disease treatment. We also found that the OHP generally ensured that contracted activities would prioritize underserved areas or populations. For example, we found that the OHP awarded an agreement to a contractor for the appropriate purpose of providing training, technical assistance, and resource materials to state staff and local health jurisdiction staff related to local oral health program planning, administration, and monitoring of program performance, outcomes, and impact. This contractor’s agreement also required the contractor to provide technical assistance for the implementation of local school-based dental disease prevention programs, with a focus on areas in which children were at higher risk for cavities.

Similar to the TCP, OHP staff monitor contractor progress generally through their review of progress reports. According to the State Contracting Manual, contract managers should monitor contracts and the progress of work to ensure compliance with all contract provisions, should maintain contract documentation, and should review invoices to verify work performed and costs claimed were in accordance with the contract. According to the OHP business operations section chief, contractor progress reports are OHP’s primary means of monitoring its contractors’ progress. She asserted that after the contractors submit progress reports, OHP staff review the reports to ensure that the contractors used Proposition 56 funding as required by state law. In one contractor’s biannual progress report for its local oral health program, the contractor indicated the status of its progress toward completing agreed-upon activities, and it provided additional evidence of the work it had performed. This evidence included links to web-based resources that the contractor had developed for kindergarten oral health assessments, oral health advisory committee meeting notes regarding topics such as the contractor’s implementation of school-based dental programs, and information on the number of children for which the contractor had facilitated the receipt of oral health-related services. The OHP typically documents evidence of its review of contractor progress reports in the form of scoring rubrics that OHP staff used to determine whether the reports contained the required components according to specified criteria or in letters that the OHP sent to contractors. In these letters, OHP staff indicate that they have reviewed the relevant progress report, summarize the contents of the contractor’s report, and explain whether the OHP has found the progress report to be satisfactory.

Notwithstanding the approach that the business operations section chief described that its staff generally take to monitor contractors, the OHP could not provide evidence that its staff had reviewed all of the progress reports submitted by seven of the 20 contractors we reviewed for reporting periods in fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23. For example, the OHP could not demonstrate that it reviewed the first annual progress report for one contractor that was responsible for providing expert consultation, technical assistance, and training for a statewide community water fluoridation project across a three-year period—this contractor’s agreement had a maximum value of more than $800,000. This annual progress report contained updates on the contractor’s progress toward completing multiple required activities throughout fiscal year 2022–23. It also noted which activities the contractor had not yet started but planned to complete in future fiscal years. However, the OHP could not provide evidence of its review of this progress report—such as the letter that the OHP typically sends to contractors—to indicate whether the contractor’s work progress was satisfactory. The chief of the OHP community and statewide interventions section explained that despite the lack of documentation, the OHP believes this review was completed. Nonetheless, the OHP should have documented its review of this report to ensure that the contractor was performing work in alignment with the requirements of the contractor’s Proposition 56 funding. We describe in the text box several more examples of when the OHP could not demonstrate that it reviewed progress reports.

Examples of OHP’s Insufficient Evidence of Monitoring Efforts for Fiscal Years 2021–22 and 2022–23

- The OHP could not demonstrate that its staff reviewed two of four progress reports and related deliverables due in fiscal year 2022-23 for a contractor with a nearly $15 million agreement to include in its local oral health programs specific activities related to education and disease prevention, among other activities.

- The OHP could not demonstrate that its staff reviewed five quarterly technical assistance summary reports submitted in fiscal years 2021-22 and 2022-23 by a contractor with a nearly $750,000 agreement to maintain the State’s System for California Oral Health Reporting—the centralized reporting system in California for schools, school districts, and county offices of education to manage kindergarten oral health assessment data.

- The OHP could not demonstrate that its staff reviewed the first annual progress report covering fiscal year 2021-22 for a contractor with a $1.3 million agreement to enhance existing COVID-19 pandemic-related training content and to create new pandemic-related training content to improve dental teams’ communication with patients about oral health.

Source: Auditor analysis of OHP agreement files.

Moreover, unlike the TCP, we noted that OHP staff generally did not provide documented feedback regarding remaining work to contractors as a part of their reviews of progress reports, likely because the OHP lacks formal policies requiring them to do so. For instance, as we describe earlier, when reviewing one contractor’s progress report, a TCP staff member indicated in a progress report analysis that the contractor had not made sufficient progress toward a particular objective and that the contractor would need to accelerate its progress to stay on schedule. In contrast, in one letter that the OHP sent to a contractor addressing its review of a progress report, we identified that the OHP staff did not provide any feedback addressing next steps related to the remaining work that the contractor had reported as not yet started—such as partnering with local colleges to increase interest in dental careers. We expect that the OHP would have provided feedback to the contractor about this work because at the time this progress report was due, this contractor’s agreement term had less than six months remaining. According to the community and statewide interventions section chief, the OHP would typically document this feedback in the progress report review letter. She also asserted that OHP staff would have provided the feedback in regular meetings with the contractor’s staff. However, the OHP was not able to provide written evidence, such as in its letter or in meeting notes, that indicates it provided this feedback.

Further, for one of the seven contractors for which the OHP did not review all submitted progress reports, the OHP also could not demonstrate that its staff had received three of the contractor’s eight scheduled progress reports. The reports were intended to provide updates to the OHP on the contractor’s performed work and to allow the OHP to determine whether this contractor met its contracted requirements. The contractor’s agreement required the contractor to maintain the State’s System for California Oral Health Reporting—the centralized reporting system in California for schools, school districts, and county offices of education to manage kindergarten oral health assessment data. This maintenance included providing phone and email technical support to schools, school districts, counties, and state staff regarding instructions for registering new users, inputting data into the system, and generating reports from the system. The contractor was also responsible for updating the system to address any barriers to the submission of complete, accurate, and timely data and other issues limiting the usability of the system. Yet for this contractor, the OHP could not provide evidence that it received the contractor’s progress reports for the first, second, and fourth quarters of fiscal year 2022–23, meaning that the OHP did not receive any documentation from the contractor about its technical support performance over these periods.

The OHP paid this contractor without sufficiently documenting that the contractor had complied with the terms of its agreement. In addition to not ensuring that the contractor submitted all of its progress reports, the OHP did not ensure that the progress reports that it received from this contractor were complete. This contractor’s agreement stated that its progress reports to the OHP must include summary information regarding its technical support, such as its average response times in providing technical support services. However, the progress reports that the contractor submitted lacked the average response times and summaries of users’ common technical issues. This contractor’s agreement also indicated that the OHP agreed to compensate the contractor for expenditures incurred in accordance with the agreement’s budget for services that the contractor satisfactorily rendered. Despite not having obtained all of the contractor’s progress reports and not ensuring that those it received were complete, the OHP paid the contractor in full—an amount of approximately $140,000—for the services the contractor purportedly rendered in fiscal year 2022–23. However, as of June 2024, OHP’s spreadsheet that it uses to track the status of invoices for this agreement indicated that the OHP had, in fact, rejected the same contractor’s most recent invoice for a similar amount of about $140,000 for fiscal year 2023–24 because of missing deliverables, such as progress reports. Therefore, we expect that the OHP would have similarly rejected the contractor’s invoice for fiscal year 2022–23 because the OHP lacked three of the contractor’s progress reports for that period as well.

The business operations section chief asserted that despite not receiving all of the progress reports for this contractor, OHP staff monitored the contractor’s performance by relying on information that the contractor’s staff shared with them during their regular meetings. However, OHP staff did not maintain evidence to substantiate these efforts, such as notes documenting the questions asked of the contractor to assess its performance. Consequently, the OHP is unable to demonstrate that the amount it paid the contractor for technical support services provided in fiscal year 2022–23 was justified.

Public Health does not have a formal policy similar to its policy for the TCP to guide OHP staff in consistently monitoring its contractors’ use of Proposition 56 funding. The lack of such a policy likely contributed to the lapses in monitoring that we identified. According to the business operations section chief, the OHP uses the State Contracting Manual and a document describing OHP contract manager roles and responsibilities as the resources it uses to train its staff. However, the document does not provide sufficient guidance to OHP staff about criteria for approving progress reports, nor does it specify corrective action that staff should take if a contractor does not meet requirements of the agreement.

In contrast, Public Health’s policies for the TCP are specific in directing its staff how to approve progress reports and the steps to take when contractors do not meet specified requirements. For example, Public Health’s guidance for the TCP directs staff to provide written justification to support their assessments of contractors’ progress for activities, and it allows for Public Health to withhold payment from contractors that do not submit timely and accurate agreement deliverables. If Public Health were to provide such explicit direction to the OHP, it could ensure that OHP staff have clear expectations regarding how to review progress reports and evaluate progress, which could in turn enable the OHP to ensure that its contractors are using their Proposition 56 funding as the law requires.

The business operations section chief indicated that the OHP plans to develop and formalize policies and procedures for OHP contract managers and program consultants—its staff positions that perform contract management related responsibilities for its Proposition 56 funded agreements—but is in the process of determining when it can complete the work.

When we inquired about why the OHP lacked policies like those that Public Health uses to guide its TCP staff, OHP staff noted several contributing reasons: the OHP is a newer program than the TCP, and the OHP did not receive additional staff it requested until fiscal year 2019–20, which affected its ability to promptly develop policies. OHP staff indicated that the shift to remote work and the redirection of staff as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic created a heavy workload for its remaining staff. The business operations section chief added that the OHP has now assigned staff to work on developing procedures and intends to hire additional staff to complete this work. Nonetheless, Proposition 56 has been in effect since 2016, and the OHP has been using its Proposition 56 funding to fund agreements since at least 2018. Even considering the business operations section chief’s explanations, it is unclear why the OHP has not been able to develop policies and procedures during the last six years, especially when the TCP has robust procedures that OHP staff could have leveraged for OHP’s monitoring efforts.

Without formal policies to monitor whether its contractors use Proposition 56 funding in accordance with their agreements, the OHP increases its risk that its contractors may use Proposition 56 funding in a manner that does not support the goals of the state dental plan to improve oral health and achieve oral health equity for all Californians.

STAKE’s Use of Proposition 56 Funding Complied With State Law

We found that STAKE allocated Proposition 56 funding toward activities that complied with state law. As Figure 2 shows, of Public Health’s programs that receive Proposition 56 funding, STAKE receives the smallest amount, only $5.1 million, to fund activities that reduce the illegal sales of tobacco products to minors.4 Public Health fulfills this mission, in part, by funding statewide STAKE Act enforcement activities, which includes undercover operations to ensure that local retailers are complying with state laws and refraining from illegally selling tobacco products to underage youth.

Although STAKE has historically spent a portion of its funding on grants to local law enforcement entities, it used the majority of the funding in fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23 to support its state-level actions to stop illegal sales of tobacco products to underage youth—both of which are allowable uses of its Proposition 56 funding.5 As of fiscal year 2021–22, Public Health ceased awarding STAKE grants to local law enforcement entities. Public Health staff explained that the department ended the practice of awarding STAKE grants because of decreases in Proposition 56 tobacco tax revenue, which resulted in the department prioritizing state-level enforcement efforts.

We found that STAKE allocated its Proposition 56 funding to activities that were consistent with the requirements in the law. Because Public Health ceased awarding STAKE grants, we did not review its process for awarding such grants. Such a review would have been similar to our reviews of the TCP’s and the OHP’s process for awarding and monitoring agreements. Instead, to determine whether STAKE allocated those funds for appropriate activities, we reviewed a judgmental selection of 10 investigation reports related to STAKE’s use of the $12 million of Proposition 56 funding that it allocated for its state-level enforcement during fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23. In each of these cases, STAKE was able to demonstrate that its staff had completed undercover sting operations at tobacco product retailers’ stores to test whether retailers would illegally sell tobacco products to underage purchasers. For example, in three of these cases, the investigation report indicated that the sting operation resulted in STAKE staff issuing a notice of a STAKE Act violation to the retailer and imposing a fine as penalty for the violation. These operations are an appropriate use of funding under Proposition 56.

Two Entities Reported Inaccurate Revenue Amounts, but All Six Entities Complied With Administrative Cost Spending Limits

Key Points

- All six entities that we reviewed met the requirement to report on their websites the amount of Proposition 56 tax revenue they received and how it was spent in fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23. However, two entities—Public Health and the University of California (UC)—reported inaccurate revenue information for specific Proposition 56 funded programs.

- The six entities adhered to Proposition 56’s requirement that limits them from spending more than 5 percent of their allocations on administrative costs.

Public Health and UC Did Not Accurately Report Proposition 56 Tax Revenue

Although all six entities we reviewed reported required information, only four accurately accounted for the funding they received in fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23 for each of their programs. State law requires that each state entity that receives Proposition 56 tax revenue annually report on its website an accounting of how much of those funds it received and how those funds were spent. For fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23, the six entities we reviewed met the requirement to report information on their websites about the amounts of funding that they received and spent. We also found that the entities each reported this information within six months of the end of each fiscal year, as we recommended in a previous report.6 We then assessed the accuracy of this information by comparing the reported amounts to the State Controller’s accounting records. For both fiscal years, California Department of Education (Education), Health Care Services, California Department of Justice (Justice), and Tax and Fee Administration reported information on their Proposition 56 receipts and expenditures that aligned with the State Controller’s records.

The other two entities we reviewed—Public Health and UC—reported information for certain programs that did not align with the State Controller’s records because the reports did not account for the actual amounts that the entities received. Public Health reported revenue and expenditure information on its website for its OHP and STAKE program each year that aligned with the State Controller’s records. It also reported expenditure information on its website that aligned with the State Controller’s records for its TCP each year. However, as Figure 3 shows, Public Health reported revenue that was $12.3 million, or 11 percent greater than the amount it received for the TCP in fiscal year 2021–22, and it reported revenue that was $13 million, or 14 percent less than the amount it received for the TCP in fiscal year 2022–23. Instead of reporting actual amounts received in those fiscal years—which Public Health was fully aware of at the time it reported these amounts—it included year-end estimates that accounted for what it expected to receive after the end of the fiscal year pertaining to the previous fiscal year. However, Public Health should have reported the actual amounts. According to Public Health, it is in the process of updating its policy to ensure that it correctly reports on its website actual amounts received.

Figure 3

Although All Six Entities We Reviewed Posted Accurate Reports Accounting for Their Expenditures, Public Health and UC Inaccurately Reported the Proposition 56 Tax Revenue That They Received in Fiscal Years 2021–22 or 2022–23

Figure 3 shows whether or not each entity we reviewed posted reports accounting for the amount of Proposition 56 revenue that they received and expenditures that they made for fiscal years 2021-22 and 2022-23 that aligned with State Controller records. Education, Tax and Fee Administration, Health Care Services, and Justice all reported expenditure and revenue amounts that aligned with State Controller records. However, as a result of not basing its report on its actual amount received, Public Health reported revenue that was $12.3 million or 11 percent greater than the amount it received for the TCP in fiscal year 2021-22, and reported revenue that was $13 million, or 14 percent less than the amount it received for the TCP in fiscal year 2022-23. Further, as a result of an error, UC reported $5.2 million less revenue than it received in fiscal year 2021-22 for the TRDRP, or 11 percent less than it received.

Source: Auditor evaluation of each entity’s Proposition 56 posting for each year, interviews with the entity staff members as appropriate, and State Controller’s Agency Reconciliation Reports for fiscal years 2021–22 and 2022–23.

Similarly, although UC reported expenditure and revenue information on its website for its Graduate Medical Education program and expenditure information on its website for its Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (TRDRP) each year that aligned with the State Controller’s records, it did not report on its website accurate revenue information for the TRDRP in fiscal year 2021–22. UC reported $5.2 million less revenue than it received in fiscal year 2021–22 for the TRDRP, or 11 percent less than it received. The UC’s director of this program explained that this amount was allocated to the program for fiscal year 2021–22, but that UC did not receive it until after the closure of the financial records for that fiscal year. However, UC did not account for the receipt of this same amount in its fiscal year 2022–23 report either. Nevertheless, UC’s practice is to report amounts received in the years that they were allocated, and therefore UC should have included the amount as revenue for fiscal year 2021–22. The fiscal year 2021–22 omission appears to have been a one-time error rather than the result of a systemic issue. The program director agreed that for future reports, UC will report on its website the full amount received in each fiscal year.

All Six Entities Adhered to the Spending Limit on Administrative Costs

State law allows entities to spend no more than 5 percent of their Proposition 56 allocations on administrative costs, which generally include expenditures for the support of state government such as equipment replacement, repair projects, and lease or rental costs. We reviewed the underlying accounting records for the six entities that we audited and determined that, during our audit period, all six entities adhered to the 5 percent limit on the use of Proposition 56 funding for administrative costs.

Recommendations

Public Health

To ensure that its staff monitor whether contractors use Proposition 56 funding in accordance with state law, Public Health should establish formal policies and procedures for the OHP for this purpose by June 2025. These policies and procedures should provide guidance for OHP staff in performing the following actions:

- Reviewing evidence of work performed by its contractors to determine whether that work meets the terms of its agreements before approving payment for these services.

- Obtaining and approving progress reports throughout the duration of its agreements, including providing written justification to support assessments of contractors’ progress, and taking steps to remediate any problems with contractor performance, such as withholding payment from contractors that do not submit timely and accurate agreement deliverables.

- Retaining documentation to demonstrate compliance with policies for each of its agreements, including documentation of contractor progress, staff reviews and approvals of contractor progress, and manager reviews of this information.

Public Health and UC

To ensure that they report accurate amounts of Proposition 56 revenue that they receive each year, Public Health and UC should each report on its respective website the amount of Proposition 56 tax revenue that it actually received, beginning with the amount reported for fiscal year 2023–24.

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards and under the authority vested in the State Auditor by Government Code section 8543 et seq. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on the audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS

California State Auditor

November 13, 2024

Staff:

Nicholas Kolitsos, CPA, Audit Principal

Sean McCobb, Senior Auditor

Nathan Drake

Rebecca McNeil

Meredith Wang

Legal Counsel:

Natalie Moore

Appendix

Scope and Methodology

We conducted this audit pursuant to the audit requirement in Revenue and Taxation Code section 30130.56. Specifically, we reviewed how Proposition 56 tax revenue was distributed, whether Public Health and its programs used the funds it received for appropriate purposes, and whether state entities complied with the reporting and administrative cost requirements of Proposition 56. This table lists the audit’s objectives and the methods that we used to address them. Unless otherwise stated in the table or elsewhere in the report, statements and conclusions about items selected for review should not be projected to the population.

Factors Related to Auditor Independence

Revenue and Taxation Code section 30130.57(g) required the State Auditor to promulgate regulations to define administrative costs for the purposes of Proposition 56. The regulations that define those administrative costs, 2 CCR §§ 61200‑61217, became effective March 14, 2018, and were used as criteria for this audit.

Assessment of Data Reliability

The U.S. Government Accountability Office, whose standards we are statutorily obligated to follow, requires us to assess the sufficiency and appropriateness of computer‑processed information that we use to support our findings, conclusions, or recommendations. In performing this audit, we relied on electronic data files that we received from Education, Health Care Services, Justice, Public Health, Tax and Fee Administration, and UC related to each entity’s receipt and use of Proposition 56 funding during our audit period. We also used agreement records for the OHP and the TCP pertaining to the Proposition 56 agreements that they funded during our audit period and accounting records from the State Controller.

To evaluate the data, we reviewed existing information, interviewed people knowledgeable about the data, and performed electronic testing of key elements of the data. We reviewed the completeness and accuracy of the State Controller’s data by comparing it to Tax and Fee Administration’s tax collection revenue data. We confirmed the completeness and accuracy of each entity’s financial records, except for UC, by comparing the records to the State Controller’s records. Because UC operates on a paperless accounting system that is separate from the State Controller, we collected and evaluated all of UC’s financial data relevant to the scope of our work.

For data from Public Health, we reviewed the completeness of the TCP’s agreement data by comparing it to online agreement archives and other records and found that the data were sufficiently reliable for using to make our testing selection. We reviewed the completeness of the OHP’s agreement data, and we identified that the data were not inclusive of all agreements funded during our audit period. We used alternate data sources to ensure that we selected from the most complete population of agreements that we could identify. Although we recognize that there is a risk that we did not select testing items from the OHP’s complete population of agreements that it funded using Proposition 56 funding during our audit period, there is sufficient and appropriate evidence to support our findings, conclusions, and recommendations. Finally, we collected and evaluated all of Tax and Fee Administration’s tax collection revenue data available through its Open Data Portal and relevant to the scope of Figure 1, but because we used these data for background information only, we did not test the reliability of the data.

Responses to the Audit

California Department of Public Health

California Department of Public Health

October 21, 2024

Grant Parks

California State Auditor

621 Capitol Mall, Suite 1200

Sacramento, CA 95814

Dear Mr. Parks:

The California Department of Public Health (Public Health) has reviewed the California State Auditor’s draft audit report #2023-046 titled “Proposition 56 Tobacco Tax: The California Department of Public Health Should Improve Its Monitoring of One of Its Tobacco-Related Programs”. Public Health appreciates the opportunity to respond to the report and provide our assessment of the recommendations contained therein.

Below we reiterate the recommendations pertaining to Public Health and our responses.

Recommendation #1:

To ensure that its staff monitor whether its contractors use Proposition 56 funding in accordance with the requirements in state law, Public Health should establish formal policies and procedures for the Oral Health Program (OHP) for this purpose by June 2025. These policies and procedures should provide guidance for OHP staff in performing the following actions:

- Reviewing evidence of work performed by its contractors to determine whether that work meets the terms of its agreements before approving payment for these services.

- Obtaining and approving progress reports throughout the duration of its agreements, including providing written justification to support assessments of contractors’ progress and taking steps to remediate problems with contractor performance, such as withholding payment from contractors that do not submit timely and accurate agreement deliverables.

- Retaining documentation to demonstrate compliance with policies on its agreements, including documentation of contractor progress, staff reviews and approvals of contractor progress, and manager reviews of this information.

Management Response:

OHP is developing an internal contract management desk manual with formal policies and procedures to ensure Proposition 56 funding complies with State law and addresses CSA’s recommendations. This manual, expected to be finalized by June 30, 2025, will include adapted policies from the California Tobacco Control program, procedures for reviewing contractors’ work, approving reports, remediating contractor performance issues, and retaining documentation. OHP will also incorporate a new Microsoft SharePoint system to improve grant tracking and deliverable management.

Recommendation #2:

To ensure that [it] reports accurate amounts of Proposition 56 revenue that [it] receives each year, Public Health should report on its website the amount of Proposition 56 tax revenue that it actually received, beginning with the amount reported for fiscal year 2023-24.

Management Response:

Public Health’s Accounting Office adjusted its processes and procedures to capture and report the yearly revenues on a cash basis, in alignment with the State Controller’s records for fiscal year 2023-24, and will follow these procedures in future years.

If you have any questions, please contact Rob Hughes, Deputy Director, Office of Compliance, at (916) 306-2251.

Sincerely,

Tomás J. Aragón, MD, DrPH

Director and State Public Health Officer

University of California

October 21, 2024

Mr. Grant Parks

California State Auditor

621 Capitol Mall, Suite 1200

Sacramento, California 95814

Dear State Auditor Parks:

Thank you for the opportunity to review and respond to the draft audit report on Proposition 56 tobacco tax. Below is the University’s response to the recommendation in the report directed to the University of California Office of the President (UCOP).

Recommendation:

“To ensure that [it] reports accurate amounts of Proposition 56 revenue that [it receives] each year, [UC] should report on its website the amount of Proposition 56 tax revenue that it actually received, beginning with the amount reported for fiscal year 2023-24.”

We agree with this recommendation and will ensure that we report on the UCOP website the amount of Proposition 56 tax revenue that the University of California actually received, beginning with the amount reported for fiscal year 2023-24.

We appreciate your team’s professionalism and cooperation during the audit process, and we look forward to implementing the report’s recommendation.

Sincerely,

Michael V. Drake, MD

President

Footnotes

- Public Health is in the process of updating the program’s name to the Tobacco Prevention Program to reflect the program’s shift from tobacco control to tobacco-use prevention. However, because Public Health’s website and documents still reference the Tobacco Control Program, as does state law, we refer to the program in this report as the Tobacco Control Program. ↩︎

- California State Auditor Report 2021-046, Proposition 56 Tobacco Tax: The Department of Health Care Services Is Not Adequately Monitoring Provider Payments Funded by Tobacco Taxes, November 2022. ↩︎

- Tobacco-related disparities are the disproportionate impacts on certain communities that suffer from higher-than-average tobacco use, exposure to secondhand smoke, or tobacco-related disease. ↩︎

- In 2016 the Legislature amended state law to raise the minimum age for lawful purchase of tobacco products to 21 years of age. ↩︎

- In fiscal year 2021–22, STAKE spent $5.5 million on state operations and $1.1 million on local grants, and in fiscal year 2022–23, STAKE spent $6.5 million on state operations and $500,000 on local grants. These amounts include payments related to allocations from previous fiscal years, such as local assistance payments to STAKE grantees to whom STAKE awarded grants before fiscal year 2021–22. ↩︎

- California State Auditor Report 2019-046, Proposition 56 Tobacco Tax: State Agencies’ Weak Administration Reduced Revenue by Millions of Dollars and Led to the Improper Use and Inadequate Disclosure of Funds, January 2021. ↩︎